Haji Ghalib: The Afghan Freed From Guantánamo Who Is Now Fighting Islamic State And Taliban – OpEd

When it comes to reports about prisoners released from Guantánamo, there has, since President Obama took office, been an aggressive black propaganda policy — firstly from within the Pentagon and latterly from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence — painting a false picture of the alleged rate of “recidivism” amongst former prisoners, a trend that has also been echoed in the mainstream media, which has repeatedly published whatever nonsense it has been told without questioning it, or asking for anything resembling proof from those government departments that are responsible. For some background, see my articles here, here, here and here – and my appearance on Democracy Now! in January 2010.

The three outstanding problems with the supposed recidivism rate — beyond the lamentable truth that no information backing up the claims has been made publicly available since 2009, and that the media should therefore have been very wary of it — are, firstly, that lazy or cynical media outlets regular add up the numbers of former prisoners described as “confirmed” and “suspected” recidivists to reach an alarming grand total, which, in recent years, is over 25% of those released, when the numbers of those “suspected” of recidivism are based on unverified, single source reporting, and may very well be unreliable. Back in March 2012, for example, as I explained in my article, “Guantánamo and Recidivism: The Media’s Ongoing Failure to Question Official Statistics,” Pentagon spokesman Lt. Col. Todd Breasseale said, “Someone on the ‘suspected’ list could very possibly not be engaged in activities that are counter to our national security interests.” (emphasis added).

The second huge problem with the reports is that even the “confirmed” rate is, very evidently, exaggerated, as it is, to be blunt, inconceivable that as many former prisoners as alleged can have been engaged in military or terrorist activities against the US. In the latest DNI report, for example, made available in September 2015, it is claimed that 117 former prisoners (17.9% of those released) are “Confirmed of Reengaging,” but no indication is given of how that can be possible. Claims can certainly be made for a few dozen “recidivists” — primarily in Afghanistan, and amongst those few former Gulf prisoners who apparently set up an Al-Qaeda offshoot in Yemen — but the figure of 117 is simply implausible.

A third important reason for disputing the claims, as noted by the Constitution Project, is that the overwhelming majority of those allegedly “Confirmed of Reengaging” — 111 of the 117 — were released under President Bush, and only six men released by President Obama — just 4.9% of those released on his watch — are regarded as being recidivists; in other words, the current threat is just 4.9%, and as a result, as the Constitution Project explained, “95.1% of detainees transferred during the Obama presidency have not reengaged.”

In the New York Times at the weekend, another more positive take on the reporting about former prisoners took place with the publication of an article about Haji Ghalib (aka Hajji Ghalib), an Afghan former prisoner, who, since his release in 2007, has become a formidable opponent not just of the Taliban, but also of efforts by Isis fighters to make inroads into Afghanistan.

Ghalib, it should be noted, is one of several dozen Afghan prisoners I identified in my research for my book The Guantánamo Files as having worked with US forces, but who ended up at Guantánamo because of rivalries with other Afghans, who took advantage of the Americans’ generally woeful intelligence, and their inability or unwillingness to cross-reference information about prisoners, to get their rivals banished to the US prison in Cuba. See the front-page story I wrote for the New York Times with Carlotta Gall, in February 2008, about Abdul Razzaq Hekmati, a heroic opponent of the Taliban, whose appeals for verification of his story were repeatedly ignored. Hekmati died of cancer at Guantánamo in December 2007, but the Bush administration never acknowledged its mistake.

In The Guantánamo Files, I wrote about Haji Ghalib as follows:

40-year old Haji Ghalib, the chief of police for a district in Jalalabad, and one of his officers, 32-year Kako Kandahari, were captured together, after US and Afghan forces searched their compound and identified weapons and explosives that they thought were going to be used against them. Both men pointed out, however, that they fought with the Americans in Tora Bora. “I captured a lot of al-Qaeda and Arabs that were turned over to the Americans,” Ghalib said, “and I see those people here that I helped capture in Afghanistan.” He explained that he thought he may have been betrayed by one of the commanders in Tora Bora, because he “let about 40 [al-Qaeda] escape so I got on the phone and cussed at him and that is why I am here.”

In 2008, Ghalib also told Tom Lasseter of McClatchy Newspapers (as later reported here) that he was detained “in a basement at an airstrip in Jalalabad during March 2003” by Special Forces troops, and added, “At night they would strap me down on a cot, and put a bucket of water on the floor, in front of my head. And then they would tip the cot forward and dunk my head in the bucket … They would leave my head underwater and then jerk it out by my hair. I sometimes lost consciousness.”

In 2012, the BBC World Service found him unemployed, “living in a cold damp apartment in Kabul,” but since then he has been at the forefront of resistance to the Taliban — although at great personal cost. 19 of his relatives, including both of his wives, his daughters, a sister and a grandchild, have been killed by the Taliban — almost all as a result of a bomb planted in a coffin — and Haji Ghalib’s descriptions of his life reveal how much he has suffered. “I don’t have good memories of life, to be honest,” he says, adding, “Everything has been fighting and killing.”

Ironically, those who falsely imprisoned him for five years now occasionally help him out. As the Times article notes, “the American military sometimes supports his men with airstrikes — although Mr. Ghalib complains that there are too few bombers and drones for his taste.”

Another sad note in the article concerns an Afghan poet and gemstone dealer named Abdul Rahim Muslim Dost, with whom Haji Ghalib was friends in Guantánamo, but who “now leads the Islamic State fighters whom Mr. Ghalib’s forces are trying to drive out of eastern Afghanistan.” As the Times put it, “Mr. Dost, a dour but quick-witted man who was known for the poetry he etched into the side of coffee cups for lack of better writing materials, was adamant that there was only one course of action after their release: Go to Pakistan and start waging jihad. He spoke of uniting the whole Muslim world.”

What I find sad about this is that, although Muslim Dost undoubtedly features in the DNI list of recidivists, it seems obvious that his profoundly negative experiences in Guantánamo must have played some part in radicalizing him. See this article from 2006, the year after his release, when he was calling on the US to return his poems, and preparing to publish a book about his experiences. Also see my profile of him here, which mentions his clashes with, and imprisonment by the Pakistani authorities following his release, and which also makes clear that it may be factors that have nothing to do with the US that have played the most significant role in turning him into an Isis soldier.

I hope you have time to read the article about Haji Ghalib, and to reflect on his bravery — and on how Guantánamo ruined his life, and led, in part, to the loss of his family, as everyone released from Guantánamo becomes a target for those opposed to the US, and often face retaliation if they don’t cooperate.

Once in Guantánamo, Afghan Now Leads War Against Taliban and ISIS

By Joseph Goldstein, New York Times, November 27, 2015

Hajji Ghalib did just what the American military feared he would after his release from the Guantánamo Bay prison camp: He returned to the Afghan battlefield.

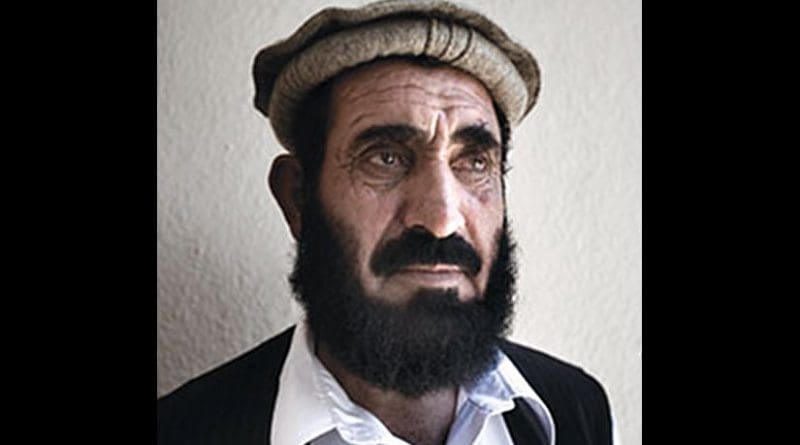

But rather than worrying about Mr. Ghalib, the Americans might have considered encouraging him. Lean and weather-beaten, he is now leading the fight against the Taliban and the Islamic State across a stretch of eastern Afghanistan.

His effectiveness has led to appointments as the Afghan government’s senior representative in some of the country’s most war-ravaged districts. Afghan and American officials alike describe him as a fiercely effective fighter against the insurgency, and the American military sometimes supports his men with airstrikes — although Mr. Ghalib complains that there are too few bombers and drones for his taste.

Accounts of former Guantánamo detainees who went on to fight alongside the Taliban or Islamic State have become familiar. So are those of innocents swept up in the American dragnet and dumped in the prison camp without recourse or appeal. But this is a new one: the story of a man wrongly branded an enemy combatant and imprisoned in Guantánamo for four years, only to emerge as a steadfast American ally on the battlefield.

At 54, Mr. Ghalib’s face is creased, and his eyes are both exhausted and watchful, as though all they really expect to see is the next bad turn that will befall his life. There have been many, including the death of both wives, his daughters, a sister and a grandchild at the hands of the Taliban.

“I don’t have good memories of life, to be honest,” Mr. Ghalib said.

In a recent interview in Kabul, he cataloged the enemies he has fought during a life of struggle — first the Soviets, during the jihad of the 1980s; then the Taliban over the next three decades; and now the Islamic State.

More slowly, he recounted the long list of relatives he lost over these decades of calamity, from a brother who died in the war against the Soviets in the 1980s to his 70-year-old brother-in-law, who was beheaded this month. The Taliban killed more than 19 relatives in all.

“Everything has been fighting and killing,” he lamented.

Now, his latest fight has even pitted him against a man he once considered a close friend: a poet named Abdul Rahim Muslim Dost, whom he lived alongside in Guantánamo.

While Mr. Ghalib chose to reject bitterness and fight on behalf of the American-backed government, his former friend Mr. Dost now leads the Islamic State fighters whom Mr. Ghalib’s forces are trying to drive out of eastern Afghanistan.

But years ago, stuck in the same camp at Guantánamo, they would spend their days debating politics and religion.

Mr. Dost, a dour but quick-witted man who was known for the poetry he etched into the side of coffee cups for lack of better writing materials, was adamant that there was only one course of action after their release: Go to Pakistan and start waging jihad. He spoke of uniting the whole Muslim world.

Mr. Ghalib had other plans. “I used to argue with them that we are Afghans and we must support Afghanistan,” he said, meaning the current, American-backed government that replaced the Taliban. It was the minority view, but he did not worry about sharing it with Mr. Dost or any of his jailed countrymen. “We were friends with each other despite our views,” he said.

How Mr. Ghalib ended up in American captivity is its own bewildering story. After building a reputation as an effective commander against the Soviets and the Taliban, he became a police chief for the new Afghan government after the Taliban’s ouster in 2001. But in 2003, he was arrested after United States soldiers found explosive devices adjacent to the government compound where he worked. That was apparently close enough. There were also several letters that linked him to Taliban figures, although American officials conceded the letters might have been forged.

One of the military officers weighing the evidence against him explained that he did not “put much credibility to any of these letters,” according to a transcript of the tribunal.

That left Mr. Ghalib flummoxed. “So why are you detaining me?”

At Guantánamo, Mr. Ghalib often explained to his captors that he had been fighting the Taliban for years and had even aided American forces at Tora Bora against Al Qaeda. He recited the names of major anti-Taliban commanders who would vouch for him.

American investigators eventually concluded that the “detainee is not assessed as being a member of Al Qaeda or the Taliban,” according to a military document outlining the evidence. Yet the military nonetheless described Mr. Ghalib as “a medium risk,” noting that he could possibly become a formidable enemy given his years of experience as a combat commander — albeit on the government’s side before his detainment.

Finally, in 2007, Mr. Ghalib was released.

He left Guantánamo angry not only over the “psychological torture” the American military put him through, but also at the Afghan government for never pushing for his release, he recalled. Yet he was determined not to let the hardship of the past four years alter the course of his life.

Mr. Ghalib decided that he would be guided by “the overall pain that my people and my country are going through — that is the most important thing.”

But his own sorrows would only grow in the coming years.

“My dream was to go back and live peacefully at home,” Mr. Ghalib said. “But nobody let me do that.”

It began with a road, or at least the idea of a road, that his tribe, the Shinwari, wanted built in Mr. Ghalib’s home district in Nangarhar Province. As a tribal elder, Mr. Ghalib took a leading role in the internationally financed project.

Almost immediately, the Taliban began to threaten him for working with the foreigners, and soon the insurgents began assassinating his relatives.

Among the first to die was Mr. Ghalib’s brother, caught on his way home from a mosque. After the Ramadan holiday in 2013, the extended family gathered at the gravesite to mourn. But the Taliban had dug up the gravesite and buried a bomb there to punish the family further.

“Eighteen members of my family were killed in that attack,” Mr. Ghalib recounted — almost all women and children.

“My family is finished,” Mr. Ghalib told The Associated Press that afternoon, calling the Taliban “inhuman.”

Back then, Mr. Ghalib had been on a local peace commission, one of many tribal elders seeking to encourage reconciliation with the insurgents. But President Hamid Karzai offered him a chance for revenge. He had little family to look after, and the Taliban would keep coming after him, Mr. Ghalib recalled the president telling him. The president got him a job as governor of Bati Kot, a Taliban-infested district straddling a highway to Pakistan. He quickly organized a local police force and began going after the Taliban.

“When I got into the government, I started to destroy them,” Mr. Ghalib recalled. The Taliban tried to placate him, he said, recalling an unusual phone call he received: The insurgent commander on the line offered to find whoever had planted the bomb at his brother’s grave and hang him.

Mr. Ghalib rejected the terms. “I told them that our enmity has just started.”

This summer, his Shinwari tribesman requested that he be transferred two districts south, to rescue a benighted region called Achin, where a belt of villages had fallen to a new threat: Islamic State fighters under the command of Mr. Dost, his old friend from Guantánamo. The militants had pushed 10 tribal elders into an explosives-lined trench and videotaped the blast that killed them.

When Mr. Ghalib arrived as the new district governor, he placed on his desk a photograph of his 2-year old grandson, killed in the cemetery bombing. “Each time I look at it, it makes my heart burst and that motivates me,” he said. “That’s why I carry on all the operations myself.”

In one battle this summer, Mr. Ghalib described how he and his son led a force of police officers and soldiers against Islamic State fighters who were threatening to overrun Achin’s small district center. After being hit by multiple roadside bomb explosions, most of the forces fell back, leaving Mr. Ghalib and his son alone to face some 15 Islamic State fighters.

“We were able to shoot many,” he said.

At such times, Mr. Ghalib said, he would not be surprised to find Mr. Dost among the jihadists shooting back at him — the rumor is that Mr. Dost is usually on the front lines.

But Mr. Ghalib said that he would have little to say to Mr. Dost at this point: “He slaughters civilians, innocent people and children.”

“We will not spare him if I face him on the battlefield,” Mr. Ghalib said matter-of-factly. And given the chance, he said, “he will also not leave me alive.”

The two last saw each other a decade ago, in 2005, in Guantánamo. The Americans had concluded that Mr. Dost was no longer a threat and sent him home.

“It is very ironic that Muslim Dost got released before me,” Mr. Ghalib said. He himself had two more years to go before the Americans finally released him, too.