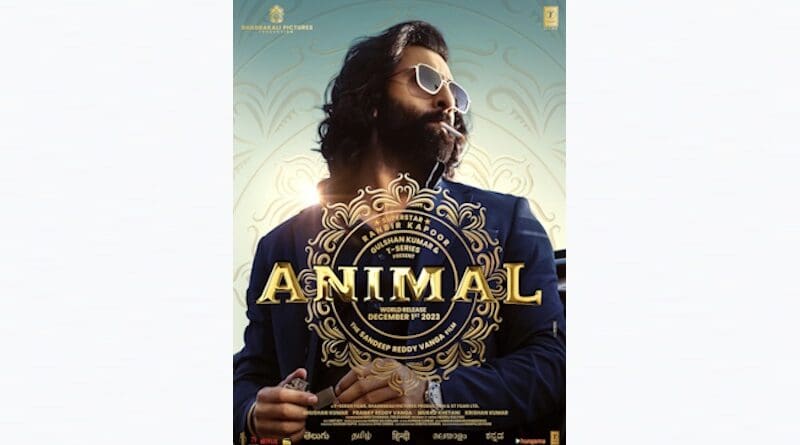

Review Of Hindi Movie ‘Animal’ (2023)

By Prakash Kona

I was curious more than anything else. I wanted to know why the movie ‘Animal’ was both controversial and popular at the same time. The fact that Sandeep Reddy Vanga is an immensely talented director, no two ways about it. At 42, he can boast of having only made blockbusters so far. His brilliance shows in his ability to create a product that appeals to a certain kind of an audience, particularly South Asian, cutting across regional barriers. He has a cross-national audience in mind and the movie ‘Animal’ with its frequent use of English by the characters, complementing the use of Hindi, makes that part evident.

The movie is largely based on a hypothesis: men, maleness, masculinity. The entire movie is hypothetical, except here and there where it is realistic. There are no normal Indian streets with people walking along the roads. No stray dogs too, such a Pan-Indian thing. Interestingly, there is no such a thing as a law and order mechanism to control the morbid appetites for violence among the male characters. This has been pointed out in comments on the movie. However, it makes sense when you see that the entire family politics of the movie is structured by a feudal worldview. The success of the movie is a reflection of the entrenched feudalism of unequal societies such as the ones in South Asia. This cuts across class, caste and sometimes the gender barrier as well. The movie is the story of feudal lords in a capitalist setting with their own private security. The owners of wealth also happen to be in possession of social and political power. Politicians, judges, the police and the army primarily exist to keep the status quo intact for the owners of private property. Hence, they are conspicuous by their absence. This is not a comment on the stylistic aspect of violence, which includes misogyny and abusive behavior, which the movie explores; we sometimes see this in Quentin Tarantino films.

In the South Asian context, this is a feudalism that celebrates manhood for its own sake, as an end in itself. It is fundamentally anti-democratic, but, then, so what! Only an emasculated nation with a colonial inferiority, where the males do not feel men enough, relishes that kind of a celebration. The emotional dynamics surrounding the father-son duo forms the central theme of the movie. The psychopathic obsession that the main character has for his father is not different from what his counterpart, the bad guy, suffers from, for his brothers. Where is the mother, protector of the wounded ego of the boy-man? What is the role of the sisters, the wife and the children who humanize the male characters and make them outgrow their narcissism? Virtually nonexistent. The subtext to this charade of maleness is homophobia which shows in the violence (a perverse form of sexual attraction) of the men towards each other. Homoeroticism is a dominant characteristic of all male-dominated societies.

Accusations of the movie being ‘misogynistic’ have to be put in a context. We cannot attribute the motives of a character to the director of the movie. By that logic most Indian movies, except those with an explicit feminist purpose, are misogynistic. The movie is portraying a feudal order. In such an order, women are not commodities to be consumed; they just don’t matter to the men. Therefore, it’s not an anti-female movie, because women are nowhere in the equation to begin with. It’s an anti-feminist movie. It is not a reaction to women fighting for their rights as women and as human beings. That’s a progressive demand. Rather, it’s a reaction to women claiming to be equal to men, which is elementary, to say the least.

A particular scene in the movie is where the main woman character is engaged to be married to a man ‘Arvind’ that she met ‘two days ago’ (a classic Indian arranged marriage scenario). The main male character confronts her and comes up with the most laughably bizarre argument to support his thesis of the Alpha male, as opposed to the pedestrian ‘Arvinds’ of the world. He says:

“You know how girls used to choose their husbands back in the days? Back in the days? Let’s go back in time. Centuries ago, there were two types of men…the alphas and the rest. Alphas were the tough ones who would go into the jungle to hunt, would divide the hunted food among themselves. They were responsible for nourishing the children and the entire community. That’s how communities operated. However, their influence extended beyond the kitchen. They also possessed the authority to choose which hunter would become their partner in parenthood. They held the power to designate the guardians…who would shield them and their offspring from the rival hunters and wild creatures. It was the women who held the reins of these crucial determinations. Back then, it wasn’t about fathers, mothers, caste, region, religion, or a job at a prestigious university. If you were there, who would you choose? I mean, a bunch of Arvinds or an alpha?”

To the question, the female character responds: “Alpha.” “Exactly,” he says, triumphantly. I understand the argument that women in the hunting and gathering stage or at least in the early societies must have depended on the men of the group for some sort of a security, to prevent being raped and violated by men from other groups. But, hunting is an activity that does not depend on toughness. Animals are mostly tougher than human beings. Hunting depends on skill. It’s about sharpness and speed along with the ability to coordinate a group. Undoubtedly, more than one man (or woman) was involved in the act of hunting and gathering food. It simply couldn’t have been one or two tough ones fighting wild beasts in the jungles. That’s a myth. It’s collective thinking and effort that goes into keeping the group alive. It’s quite plausible that “a bunch of Arvinds” could do the job better than a grossly self-centered “Alpha.” Women, with the slightest survival instinct, would prefer to hang around the “Arvinds” rather than the “Alpha,” who could end up endangering the group, only to prove a point that he is, in some mysterious fashion, better than the others.

In the movie, the team that the main character chooses for himself is built around the same principle of the brotherhood of men, a feudal concept. They commit themselves to serve the main character, with the lines: “Building relationships is like writing on sand with sand, and being true to them is like writing on water with water. And we brothers will be true to our bond and write on water with water.” Consumerist societies that are a product of capitalist ideology rely heavily on individualism. In principle, consumerism and feudalism are incompatible bedfellows. To his credit, the director is able to create a product out of the feudal world for the consumption of the audiences who share a longing for such a world. The nostalgia for the feudal world is a nostalgia for unconditional togetherness, a social group with the father-figure at the top. The movie plays on the nostalgia for a world when men were men, they stood for each other, they did not allow women to come in between them. They loved and they killed, but they did it as men with “honor.” Strangely, this golden world of ‘honorable’ men never existed. Women, children, men who were not quite men, women who were not quite women, those that were neither men nor women, they were always present since the beginning of history. They were at the early stages of human evolution just as we see them today. The “Alpha” male is a myth concocted by men with wealth and power to convince themselves that they deserve the privileges that seem so natural to them.

Although the movie gives the impression that the family of the main character is economically prosperous, simply observing that none of them ever go to work, it is evident that they are busier settling scores rather than taking care of their company. In his “Notes on Italian History,” Gramsci observes, “The old feudal classes are demoted from their dominant position to a “governing” one, but are not eliminated, nor is there any attempt to liquidate them as an organic whole; instead of a class they become a “caste” with specific cultural and psychological characteristics, but no longer with predominant economic functions” (Prison Notebooks 115). This is a “caste” of men “with specific cultural and psychological characteristics,” who have the time for unproductive rivalries. In attributing “predominant economic functions” to this “caste,” the movie straddles the feudal and the neoliberal order.

The movie is reflective of how feudal people think. They operate as a caste and their feelings are casteist, by definition. They see the world as superiors and inferiors, never as equals. The movie ‘Animal’ is the daydream of an average Indian; to belong to a “caste” that guarantees supremacy to their social group. The guiding passion of such a caste is to decimate members who do not belong to your group or do not share your system of values. To eliminate all opposition is to ensure your own security as a group. The plot is simple: destroy or be destroyed, kill or get killed. The pseudo-scientific idea behind the argument that you must eliminate others in order to survive, is that, it is the guiding principle of human evolution. Simply examining the tremendous odds for the early human person to manage in the face of the vagaries of nature, undoubtedly, it is intelligence and boundless compassion that enabled evolution, or else the species would long have disappeared, thanks to the Alphas, who thought no end of themselves. In other words, we owe human progress to the seemingly ordinary “Arvinds,” who paid attention to the presence of others in the process of preserving themselves.

On the brighter side, the movie has no songs of couples running around trees making promises of eternal love to each other. Film going masses had enough of that, which is why, crude scenes, with sexual innuendos, appealed to the anti-romantic streak of a primarily male audience, unwilling to make emotional investments in their partners. The mise en scène for the ‘jamal kudu’ song, with Abrar Haque (played by Bobby Deol) making the coolest onscreen entry ever for a Hindi movie villain, with the exception of the more dramatic entry of Gabbar Singh (played by Amjad Khan) in Sholay (1975), is something I have not seen in a long time. The scene I found painful to watch was when, at gunpoint, the main character asks the wives, one of whom is pregnant, and the mother to disclose the whereabouts of the villain. Even in a fictional representation, for someone to expect a wife or a mother to disclose where their husband or son is, knowing full well that the intention is to kill him, seemed to me cruel beyond words.

Despite the conventional setting, the scenes depicting the husband and wife are realistic to a fair extent, especially the part when the main character confesses to the wife that he cheated on her with another woman. That’s when the wife has a meltdown and condemns the husband for his obsessive attachment to his father, whom she wishes were dead. In a way she has a point. As long as the ‘patriarch’ of the family is alive, it means the system of patriarchy makes it impossible for any honest conversation between the husband and wife. The emotionally castrated son is trapped in the conundrum of having to prove to himself that his sexual prowess is greater than his father’s and so he qualifies for the patriarch of the family much more. For this, the main character as the husband has to depend on other men to keep his fragile ego intact; it means the wife never gets to tell him the truth about himself that he needs to be made aware of. The whole point of keeping women out of the equation is because most men don’t wish to face the truth about themselves, that deep down they are vulnerable and in need of help and that they don’t need an external enemy to destroy them. The startling irony is that one is always one’s worst enemy; to know this, one has to be in an honest relationship, because that is the only place where one gets to know the truth about oneself.

References:

Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. Eds. Selections from The Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. International Publishers, 1992.