Fighting Corruption With Corruption: Europe’s New Normal? – OpEd

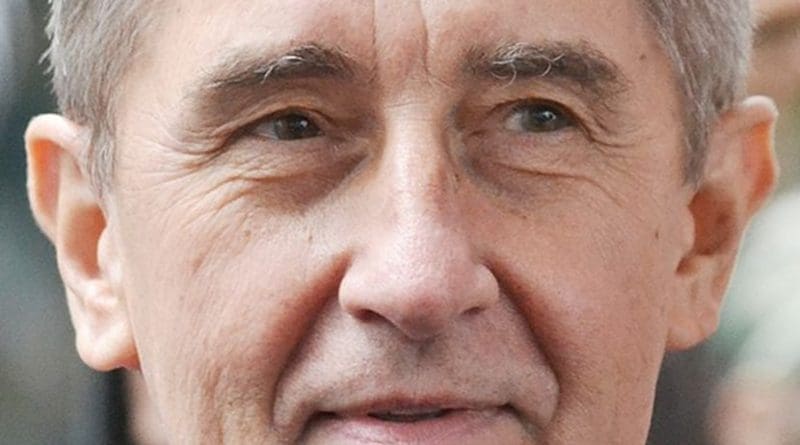

With the victory of another anti-Establishment party, the European political landscape is set to shift once more. Czech Prime Minister (PM)-elect Andrej Babiš, billionaire business man-turned politician, is set to shake up his country’s political system as he is inching closer to forming a rare minority government. Emerging victorious in the Czech parliamentary elections this October, Babiš is bad news for European transparency. However, despite having pledged to weed out corruption in mainstream Czech politics, Babiš himself faces corruption and fraud charges, making him symptomatic of a new trend in Europe where using media channels to deflect, profit and achieve power is becoming the new normal.

The Czech Republic’s second richest man won the parliamentary elections with almost 30% of the popular vote. Owning a sprawling conglomerate of chemical and food companies, Agrofert, the 63-year-old holds a fortune of an estimated $4 billion, making him simultaneously the largest private employer in the Czech Republic. All the while the campaign of Babiš’ party ANO (centrist movement Yes) centered on an anti-establishment and Eurosceptic platform, attacking traditional parties for corruption, elitism, and incompetent management of public finances.

These are bold accusations from a man who has been heavily attacked for his own suspected wrongdoings. The PM-elect allegedly made his fortune thanks to the same system he now attacks – and his road to riches has left a long paper trail. In 2016, the European Union’s anti-fraud office (OLAF) opened an investigation into the circumstances under which Agrofert benefitted from EU subsidies to the tune of some €2 million. He stands accused of hiding ownership of a resort built by his company in 2008, when Agrofert was not eligible for subsidies. Worse, while holding the Finance Minister position, then-Prime Minister Bohuslav Sobotka and his government resigned in protest over Babis’ involvement in tax evasion schemes during his time as Agrofert CEO. A parliamentary request to explain his opaque financial dealings of that time has gone unheeded.

The fact that Babis will take up public office while under EU investigation is concerning enough. However, his ascent is also problematic for another reason. As Czech Finance Minister he already proved his ability to disrupt EU anti-corruption efforts. Last year in Brussels, he made a name for himself for effectively scuttling the EU’s plans to clamp down on tax fraud, at a time when consensus on the matter was finally about to be reached. Arguing that individual VAT fraud was a bigger problem than corporate tax dodging, Babis has delayed the passing of the EU’s tax avoidance directive by threatening to veto Commission proposals. The directive was eventually adopted, albeit significantly watered down, giving member states considerable leeway in the design and application of anti-avoidance rules.

Considering his unclear tax record as Agrofert chief executive, this move was perhaps not surprising, and Babis seemingly got what he wanted. Now it stands to reason that as PM his power to stall European attempts at reining in corruption will only grow. To a large extent, this power will be underpinned by his vast influence over the Czech Republic’s media landscape. Over the years, Babis has purchased various media outlets, and now controls two of the country’s most important agenda-setting newspapers, a popular TV channel and a radio network. Not only has he utilized these extensively to dispel the allegations levied against him, he furthermore employed his connections to roast his opponents, disseminate praise for his efforts, and cut off journalists looking too deeply into his affairs.

Without a doubt, this has helped him in the polls. A prime example of the spin he succeeded to place in the media regarding his person was a conflict of interest bill passed in the national parliament in September 2016. The law – aimed at Babiš himself – bans ministers from owning stakes in media firms. In blatant disregard of the law’s stipulations, Babiš leveraged all media channels available to him to portray the law’s enactment as a witch-hunt against him. As such, ANO’s credentials were thereby strengthened, and Babiš portrayed himself as a victim yearning for transparency among a deeply corrupted political elite.

Unfortunately, Babiš’ tactics are merely the most recent example of how the media is used for personal whitewashing, where the premise of politically-motivated prosecution is the defense of choice. For example, Romanian millionaire Alexander Adamescu escaped justice in his home country by seeking refuge in London after Romania’s anti-corruption agency issued a European Arrest Warrant on his name. Using top-tier British media to portray himself as a victim of political persecution, he has been trying to absolve himself of any involvement in the large-scale fraud uncovered at the insurance company he chaired in order to prevent extradition to Romania.

While Adamescu plays the victim, Hungary’s PM Victor Orbán’s tactics adhere more closely to those of Babis. Aiming to dictate the views society should be exposed to, omnipresent Orban-ally Lőrinc Mészáros has acquired one of the biggest media outfits in the country, Mediaworks, which owns several regional daily newspapers. He also bought stakes in TV broadcasters in what amounted to a broader move of Orban-affiliated tycoons to gain an ever-greater share of the media landscape. A report published in August estimates that the editorial agendas of “at least one hundred Hungarian news outlets” is now firmly under the control of Orban and his cronies.

Although Babiš promises a more transparent future, combining business, politics and power legitimizes what has now become a large-scale threat to democracy. Romanian, Hungarian, and Czech cases of corruption among politicians and business people are seemingly becoming the norm. Lack of probity combined with anti-EU sentiments severely means that the democratic slip will continue and jeopardize constitutional safeguards, media pluralism, and civil society. As the previous examples illustrate, the fight against corruption is far from over.

*Nicholas Kaufmann is a public affairs consultant based in Brussels.