Pakistan’s New Top General: Implications For Civil-Military Relations And Foreign Policy – Analysis

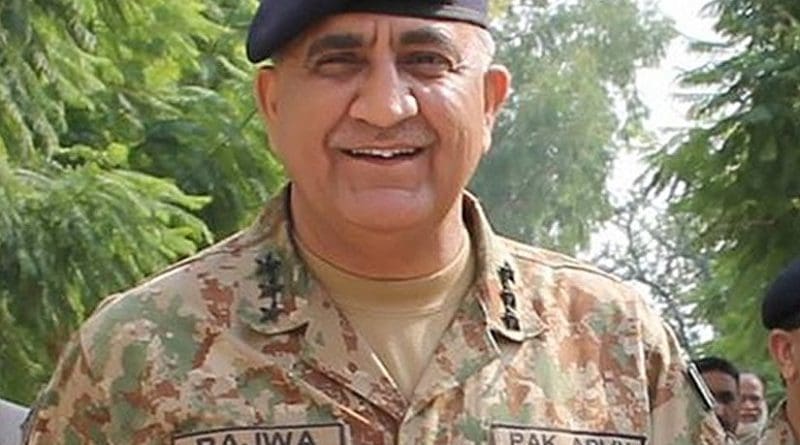

On November 29, Lieutenant-General Qamar Javed Bajwa became Pakistan’s new Chief of Army Staff (COAS), succeeding General Raheel Sharif. General Sharif has benefited of tremendous support among the Pakistani society. The success associated with the counter-terrorism military operation Zarb-e-Azb and security operations to curb violent crime in Pakistan’s economic metropole, Karachi, have been major factors contributing to his popularity.

Two striking phenomena preceded the appointment of a new COAS in Pakistan.

Firstly, it was for the first time in the last decades when the COAS implemented the due retirement and has not sought for an extension of the mandate. Secondly, the procedure of finding a qualified and suitable successor gravitated around a small crisis, characterized by a rare deficit of candidates fulfilling the seniority criteria for this post. Is the Pakistani Army in decline? If the Pakistani Army is in decline, does this open a window of opportunity for the civilian government to consolidate their position in democratic security governance? How will the new COAS impact democratic civilian control and Pakistan’s foreign policy, particularly vis-á-vis India and the United States?

The appointment of the new COAS by Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif under constitutional provisions represented a strong moment of glory for the civilian government of Pakistan from the country’s independence in 1947. The outgoing COAS, General Raheel, and the Defense Minister Khawaja Asif, the main persons in a position to make a formal recommendation to Prime Minister Sharif on the new Chief of Army Staff, refrained from publicly making a nomination.

Prime Minister Sharif’s appointment of General Bajwa, who was actually at the bottom of the list of favorites, also shows the government’s new firmness over the military establishment. Unlike the other candidates, General Bajwa believes that the major threats to Pakistan’s national security are domestic terrorism and not external. This vision is likely to bring a sustainable shift in the balance of civil-military power in Pakistan, as well as in the country’s foreign policy, most particularly with India and the United States.

Implications on Civil-Military Relations

The designation of a new Army Chief has two major implications for Pakistan. At domestic level, the new COAS’ policy approach and preferences will have tremendous consequences on civil-military relations. Under democratic principles, the military establishment is placed under the political control of the civilian federal government, guaranteed by the Art. 243 of the Constitution of Pakistan. However, a notorious tradition of coups d’état and military inference in politics have jeopardized democratic statebuilding.

While Pakistan’s transition to democracy has been internationally acknowledged, the introduction of military courts in 2015 to judge terrorism-related offenses has been widely criticized. Democracy does not solely consist of free elections, but it rests on a solid system of civil liberties, human rights and inclusive power-sharing mechanisms. Therefore, the policy and approaches of the new COAS and his relationship with the civilian institutions and Pakistani civil society are intrinsic to the project of democratization. The lack of strong candidates might suggest the erosion of the military establishment in Pakistan and an inclination of the balance of power towards the civilian institutions.

Terrorism, separatist conflict and sectarian violence have provided ground for extensive military interventions in the last decade and have delayed the democratization process in Pakistan. That security and democracy can stay in a nearly zero-sum relationship is not surprising. The terms and conditions of the state of emergence in France enacted in reaction to the series of terrorist attacks in 2016 have been interpreted as a downgrade of democratic principles and were harshly criticized by human rights observers.

However, the situation in Pakistan is much more concerning. The army in Pakistan is claimed to be accountable for numerous disappearances of activists, e.g. in Baluchistan, or elsewhere in Pakistan. The enactment of military courts and re-institution of death penalty as part of the National Action Plan for countering terrorism, in the aftermath of the massacre on the military school in Peshawar in 2014, have been strongly opposed by democracy advocators at both domestic and international level.

While containing terrorism requires military measures, efficient and sustainable counter-extremism models need to minimize the emergence of potential for injustice and abuses, which would reinforce the spiral of radicalization and extremism.

In the fight against terrorism, the new COAS is anticipated to continue the operation Zarb-e-Azb, which made his predecessor so popular. An explicit focus on domestic terrorism is likely to incrementally improve the security situation. General Bajwa has shown interest to liaise more with the media and civil society, which will consolidate democratic institution-building and resilience in Pakistan.

Implications on the Foreign Policy with India

Secondly, the policies of the new COAS will have a tremendous impact on Pakistan’s foreign policy, most notably with India and the United States.

Pakistan’s diplomatic relations with India have been predominantly tense since the transfer of power from the British rule and subsequent partition in 1947. The two neighboring countries have fought three wars so far. Disputes around the Kashmir region and allegiances of mutual interferences in each other’s internal affairs and support for militancy (India in Baluchistan and Pakistan in Jammu and Kashmir) have prevented a harmonic policy between the two neighbors. Nuclear deterrence and the strategic policy of both countries have generated a security dilemma in South Asia: how much weaponry is enough?

India’s acquisitions of military equipment in 2016 have created a new asymmetry. The new Pakistani COAS might use this reference to justify new tactical acquisition for Pakistan in the near future. While this would amplify the two states’ perceived confidence in their defense apparatus, in reality, a continuation of the arms race policy would further boost the insecurity factor in the region. With such military arsenals, any escalation of tensions between the two neighbors, e.g. skirmishes along the Line of Control (the de facto border between India and Pakistan in the Kashmir region) which occur on a nearly daily basis, might result in an all-out (nuclear) war. Nonetheless, the new COAS’ concern with primarily countering domestic threats suggests that rather dovish instead of hawkish politics with India are to be expected.

Implications on the Foreign Policy with the United States

The United States have been the main weapons suppliers to Pakistan, mainly in return to strategic aid. Pakistan was the major geo-strategic US partner during the operations in Afghanistan after 9/11 and the proxy-war against the Soviet Union in the late 1980s.

Relations between the two countries have dramatically changed after the CIA operation of capturing Osama bin Laden in Abbottabad in 2011. Allegations of involvement of the US-based organization Save the Children in tracing bin Laden has acerbated mistrust between the two governments and raised suspicion against the activity of international NGOs in Pakistan.

Drone strikes conducted by the United States have been repeatedly condemned as a breach of national sovereignty by the Pakistani government. However, diplomatic relations between the two countries have been relativized by Pakistan’s dependence on military aid and equipment from the United States. Pakistan’s new alliance with China, concretized through the Pakistan-China Economic Corridor, is likely to incline the balance in the favor of Pakistan.

The US President-elect Donald Trump has reiterated his foreign policy plans to reconsider relations with China on several occasions. This abrupt policy shift might indirectly change the status of China’s allies, in this case Pakistan, in US’ more or less enemies. In the top of this, Trump is likely to stop military assistance to Pakistan and US military involvement in Afghanistan, which would have broader implications for the security situation in the region.

Trump’s anti-Muslim campaign rhetoric ahead of his election was rather inimical to a friendly foreign policy with Muslim countries like Pakistan. However, the recent personal phone call with Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif suggests productive US-Pakistan relations in the near future. The appointment of the retired Marine Corps General James Mattis as Defence Minister might bring a new vigor on the Washington-Islamabad axis.

In the light of the growing risk of transnational terrorism, security has become a main priority on the international agenda. Worldwide increasing military expenditures are correlated with increasingly militarized approaches and prominence of armed forces in eliminating security risks and providing stability, although, from a sustainable perspective, this trend alone is unlikely to foster societal resilience and democratic stability. Against this critical background, the approach of the new COAS of Pakistan is particularly important, both in terms of domestic and foreign policy.

About the Author:

Cornelia Adriana Baciu is PhD candidate at the School of Law and Government. Cornelia has conducted two field trips to Pakistan as pre-doctoral fellow of the ZEIT-Stiftung Hamburg in 2015. Previously, she worked as a Risk Analyst at a security management company in Konstanz, Germany, where she focused her work on armed conflict, civil unrest and political instability in Asia and the Middle East. Cornelia Adriana Baciu studied Politics and European Studies in Germany, India and Romania and completed an internship at the Terrorism Prevention Branch, United Nations.

Contact: [email protected]; [email protected]

This is really an in-depth analysis.Kashmir remains the core cause of tension between india & Pakistan, if it’s resolved it would certainly bring peace to entire south Asia.Moreover India’s frequent statements regarding IWT can lead to full scale war.

#Nice write-up Cornelia

I think Pakistan and India fought four wars, 1947-48, 1965, 1971 and 1998. For me the article i think lack some theoretical consideration when it come to Pakistani Military in terms of decision making about new COAS, CMR and India.