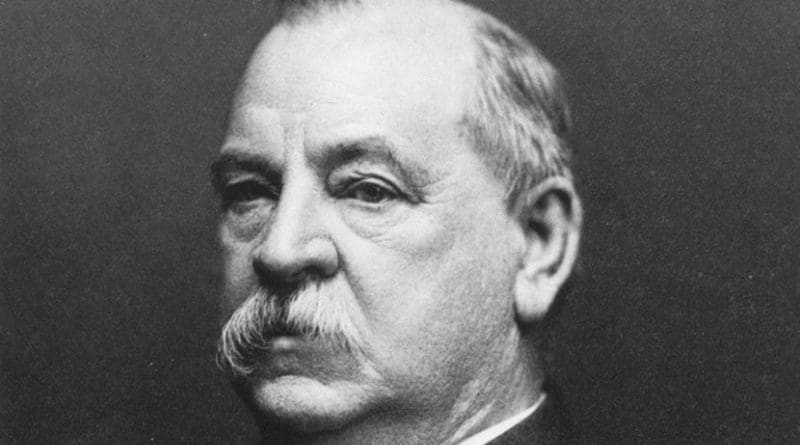

Why Grover Cleveland Is Mostly Forgotten Today – OpEd

By José Niño*

It’s no secret that court historians do their best to discredit the Gilded Age.

The Gilded Age’s environment of relatively small government allowed America and the rest of the Western world to thrive. As a result, this area had standout figures in both the private sector and the political realm. One of those political heroes was none other than Democratic President Grover Cleveland.

Nicknamed “Grover the Good” for his upstanding character and fights against political corruption, Cleveland was the only president to serve two non-consecutive presidential terms.

Cleveland had a strict constitutional vision of governance, where he envisioned the president as the executor of laws passed by Congress, rather than a quasi-legislator. Ivan Eland’s research in Recarving Rushmore depicted Cleveland as an enthusiastic champion of the Presidential veto. According to Eland, Cleveland “admirably vetoed more bills — mostly legislation that benefited special interests at the expense of the general taxpayers — than all previous presidents combined.”

Unlike the modern-day Democratic party, or the Republican party, Cleveland was a staunch critic of government subsidies and crony privileges. He saw no constitutional justification for welfare and famously stated: “Though the people support the government, the government should not support the people.”

Cleveland was also a staunch defender of the gold standard throughout both of his presidencies. These were periods when the Populist movement clamored for bimetallism, a dual gold and silver standard which often drove up silver prices through government purchases of silver that were necessary to maintain a fixed price ratio between gold and silver. This movement made some headway at the federal level when the Bland-Allison Act was passed during Rutherford B. Hayes’ administration, despite Hayes’ veto.

Cleveland had to spend much of his second term cleaning up the messes left by his predecessor, Benjamin Harrison. Harrison’s high tariff policies, spending binges, and loose monetary policy set the stage for the Panic of 1893. Instead of relying on government “solutions” like 20th-century presidents did during recessions, Cleveland spearheaded the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, and vetoed Congress’s inflationary proposal to have the Treasury convert silver stock into coins.

He also vetoed hundreds of superfluous spending bills, and courageously stood up to foreign policy interventionism when he decided to nix the treaty that would have paved the way for the annexation of Hawaii.

Cleveland’s presidency, apart from the Harding and Coolidge administrations, was one of the last instances of relatively restrained federal policy in the United States. The rise of the agrarian Populist Movement and the urban Progressive Movement, which coincided on many issues such as an active state role in the economy, succeeded in reversing the effects of many of Cleveland’s policies.

Although he ended up losing the general election to William J. McKinley in 1896, the nomination of William Jennings Bryan as the presidential candidate of the Democratic Party marked the beginning of the end of the Democratic party’s period of moderate libertarianism. McKinley discarded Cleveland’s restrained foreign policy through his execution of the Spanish American War, which marked the beginning of the U.S’s imperialist ambitions and made the U.S. receptive to a number of foreign adventures.

The full realization of Progressivism came about during the Wilson administration, which saw the introduction of the income tax, the creation of the Federal Reserve, and the U.S’s participation in World War I. The war would pave the way for increasing levels of federal interventionism, save for the Harding and Coolidge administrations where there was a strong reaction against Wilson’s ambitious Progressive project. However, these administrations were an aberration in the greater scheme of things. In terms of both foreign and domestic policy, Wilson continues to cast a far greater shadow today than Cleveland, and Cleveland’s preference for laissez faire is considered by many modern historians to be quaint at best.

*About the author: Jose Nino is a Venezuelan-American political activist based in Fort Collins, Colorado. Contact: twitter or email him here.

Source: This article was published by the MISES Institute