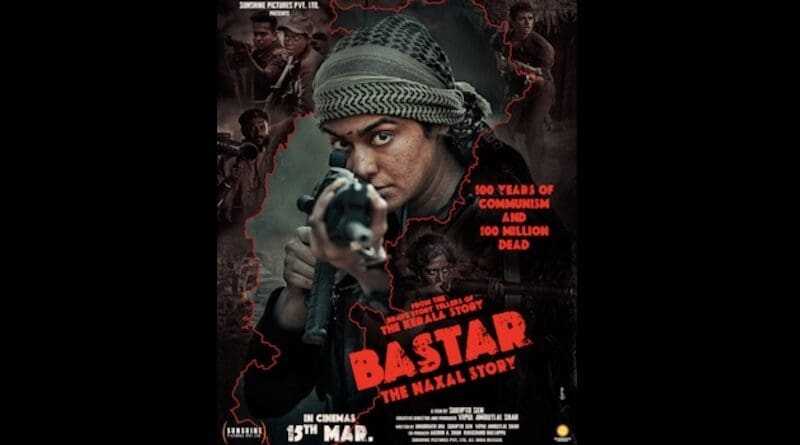

On Screen Portrayals Of Left-Wing Extremism: ‘Bastar, The Naxal Story’ As Example – Analysis

Filmmakers adapting non-fiction work—especially those on conflict and terrorism—often struggle to stick to the original story. Filmmaking admittedly allows for the dramatisation of factual nuances given the need to tell a long story in a short timeframe. The struggle, however, is even more stark when a film doesn’t rely on adequate research, and is in fact seen as being based on reality.

This article looks at the recent example of ‘Bastar, the Naxal Story’ (referred to as ‘Bastar’ hereafter), which claims to have been based on the “real-life incidents of Naxals in Chhattisgarh,” to highlight how such films, because they are so poorly researched, can lead to a distortion of facts on the ground—including official policy. This can have negative consequences both for public perception and official government narratives. That Bastar has received extremely negative media reviews is therefore neither unreasonable nor harsh. Reviews by critics, in broad terms, also underline the film’s failure to adhere to established facts and figures about conflict dynamics.

Most films aim to deliver a message, socially relevant or otherwise. To drive home such a point, filmmakers have the liberty to exercise artistic license, which may stray from a strict and ‘within-the-set-boundaries’ interpretation of the subject. However, ‘artistic license’ becomes irrelevant when the film markets itself as based on reality. Bastar draws attention to left-wing extremism (LWE), once dubbed as India’s biggest internal security challenge. Director Sudipto Sen, during the pre-release publicity for the film, described it as a “personal story.” He said he “followed what is happening in Naxalism,” and had seen the “evolution of this movement.” The lead actor Adah Sharma insisted in her interviews that the movie is based on reality and should therefore “shake people” who have “patriotism in their hearts.” There is no ambivalence that Bastar is a mere work of fiction. Rather, it is a film that seeks to bring attention to a threat it believes looms large on India’s horizon.

That, however, isn’t fact. That LWE is no longer the threat it used to be is apparent in the government’s repeated assertions. There were 32 LWE-related incidents of killing in 2023—a significant reduction. The home minister has also predicted that whatever remains of the LWE threat will be eliminated in 2-3 years.

In Bastar’s narrative, however, LWE is a thriving existential threat to the country, having claimed the lives of 50,000 to 60,000 innocents, including 15,000 security personnel. Interestingly, official fatality figures in LWE theatres are a fraction of this highly exaggerated claim. According to the South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP), which keeps track of Home Ministry data and also compiles information from open sources, the total LWE-related fatalities in the period 6 March 2000 to 12 March 2024 is 11,294, including 2,681 security personnel. The film even compares LWE with terror groups like the Islamic State and Boko Haram, which portrays an extremely fragile understanding of how the extremist group operates and extracts support from tribal constituencies.

Inflated figures and false comparisons aren’t Bastar’s only shortcomings. The film errs grievously in identifying the context within which LWE thrived, the real perpetrators of LWE violence, and the drivers of an extremist movement that once captured nearly one-third of the country’s landmass. While the film focuses on armed rebels in forested areas, equal attention is directed to ‘left-liberals’ at educational institutions like Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU)—the name is beeped out but made quite clear in the film’s teaser—who apparently are central to the plan of breaking the country from within.

One of the reviews points to how the film is all about the “same story, new villain.” Although the female protagonist doesn’t explicitly verbalise the term, at a certain point she appears to be referring to so-called ‘urban naxals’, a highly contested political expression that even the Home Ministry has categorically denied ever using. The CPI-Maoist has an ‘Urban Perspective’ document which outlines the steps necessary to build the movement in India’s urban areas, as a precursor to overthrowing the government of the day. This plan however never came to fruition as the group’s influence—even at the height of the movement—was confined to the country’s forested areas. Bastar, on the other hand, embraces the conspiracy theory that the strength of the LWE movement is based in urban academic institutions like JNU, where student activists conspire to break the nation. Such attempted vilification of public-funded and academically boisterous institutions like JNU point to the filmmakers’ benightedness, if not an agenda-driven artistic endeavour. It is a reflection of their gross ignorance of the context within which LWE once prospered and subsequently weakened.

In the film, the female protagonist’s only prescription to eliminate the threat seems to be to shoot the perpetrators and their supporters. This simplified solution to a complex problem is a wholesale misreading of the threat. More importantly, it is a trivialisation of the government’s efforts to not only contain the threat but also eliminate it from large parts of the country. The number of police stations reporting LWE-related violence has reduced from 465 in 96 districts in 2010, to 171 in 42 districts in 2023. As per government statements, this was achieved through a “multi-pronged strategy involving security-related measures, development interventions, and ensuring rights and entitlements of local communities.” Bullets didn’t deliver these results, but Bastar would have us believe otherwise.

Before Bastar, Bollywood films on LWE were either built around around the impact of conflict on people’s lives or stuck to the film industry’s formula of reductionism—i.e. making a single villain responsible for the entire conflict, which ended with his killing in the hands of the male protagonist. The film ‘Newton’, India’s official entry to the Oscars in 2018, narrated the story of an election official in charge of a polling station in LWE-affected Chhattisgarh. It did so subtly and with great effect, without compromising the film’s dramatic value or the reality it drew from. Another LWE-focused movie, ‘Chakravyuh’, made in 2012, on the other hand, as a typical, action-oriented potboiler, didn’t make any claims to be based on reality.

Bastar errs grievously by sticking to neither of these formulas. Its claim to be portraying reality falls short on multiple grounds. It is an attempt to provide a diatribe against communism, which instead merely adds to the ever-expanding pool of fake news, misinformation, and disinformation, all of which the government is in fact trying to address.

This article was published at IPCS