The Proxy Wars: Ukraine Today, Tomorrow The Philippines? – OpEd

Ukraine President Zelenskyy and Philippine President Marcos Jr enjoyed landslide election victories as candidates for peace and development. In Ukraine, those dreams turned into ashes, while nuclear risks soared with military alliances. What about the Philippines?

A year ago, when President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. still campaigned for Philippine presidency, he vowed that his administration would advocate for peace and unity. When Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelenskyy campaigned for his presidency in 2019, he promised to end Ukraine’s protracted conflict with Russia and portrayed himself as the candidate for peace and development.

Marcos said he would create jobs and support growth by improving tourism, education, and modernizing agriculture, while also pushing for infrastructure developments, tax overhaul, and climate-change mitigation. Zelenskyy pledged he would develop the economy and attract investment to Ukraine and restore confidence in the state.

President Marcos has repeatedly stated that “the Philippines shall continue to be a friend to all, and an enemy to none.” He has also stressed the importance of China’s Bridge and Road initiative (BRI) to Philippine development. Zelenskyy pushed for the BRI for a peaceful and stable future. As he said to President Xi Jinping, Ukraine could become a “bridge to Europe” for Chinese investments.

Washington and the NATO had different plans for Ukraine. Just as they may have for the Philippines.

“The big deal”

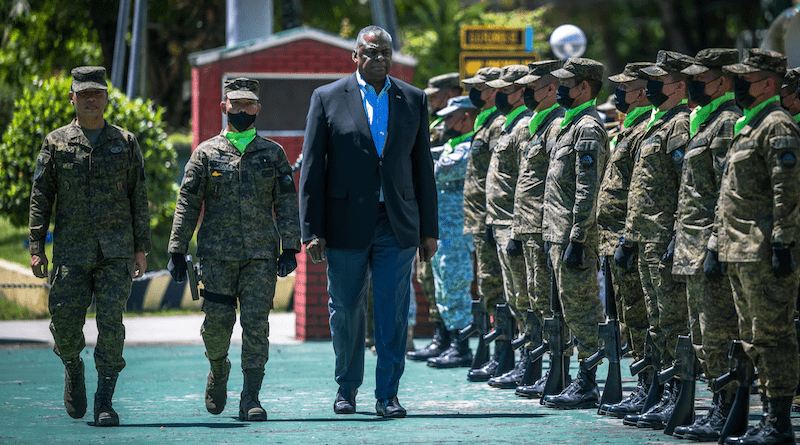

In 2019, when Ukrainians voted for peace, US Congress was already working on a bill to make Ukraine a “major non-NATO ally.” It is a designation that Washington has also applied to the Philippines. Hence, the recent, rushed visits of Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin in both countries.

In Asia, the Biden administration has struggled to integrate its military alignments before the ASEAN and China finalize a code of conduct (COC) for the South China Sea (SCS). Seeking to navigate between Washington and Beijing, Marcos admitted recently that the SCS issue is something that “keeps me up at night.”

However, from Washington’s standpoint, the primary mandate of a client state is to support US national security because that state’s national interest is seen as subordinate to the “controlling state.” There are no free lunches.

During Austin’s courtesy call at Malacañang, Marcos said diplomatically that the US will always be involved in the future of the Asia-Pacific region. Austin was more specific with his Philippine counterpart Carlito Galvez Jr. “It’s a big deal,” he said. The US will get access to four more locations under the 2014 Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) and they will also resume joint SCS patrols.

Allowing US forces to broaden their footprint in the Philippines supports Biden administration’s moves to “better counter China” in Southeast Asia and that includes any potential future confrontation over Taiwan.

Unlike permanent bases, rotational deals are more flexible strategically and more cost-efficient economically. They shift geopolitical risk from Washington to Manila, just as has been the case with Kiyv and Taipei. If things take turn for the worse, they ensure that American soldiers will stay out of harm’s way.

The last stand, however fatal, is a client state privilege.

The future and nuclear risks of a “major non-NATO ally”

Galvez tried to allay nuclear fears on the EDCA expansion. Yet, such assurances have not been reliable in nuclear matters, as I warned 2 years ago (“From peaceful, nuclear-free ASEAN to battle-ready Indo-Pacific?” TMT, Oct. 18, 2021).

Furthermore, the US, the UK and Australia may unveil a nuclear submarine plan under the trilateral AUKUS when their leaders gather in Washington in mid-March.

The highly controversial deal has triggered arms races and nuclear proliferation in Asia. It violates the Southeast Asian Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Treaty. It would seem to violate the constitution of the Philippines, which has ratified the legally-binding Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). And it is opposed by China (“US Big Defense and Australia’s nuclear crossroads,” TMT, Nov. 21, 2022).

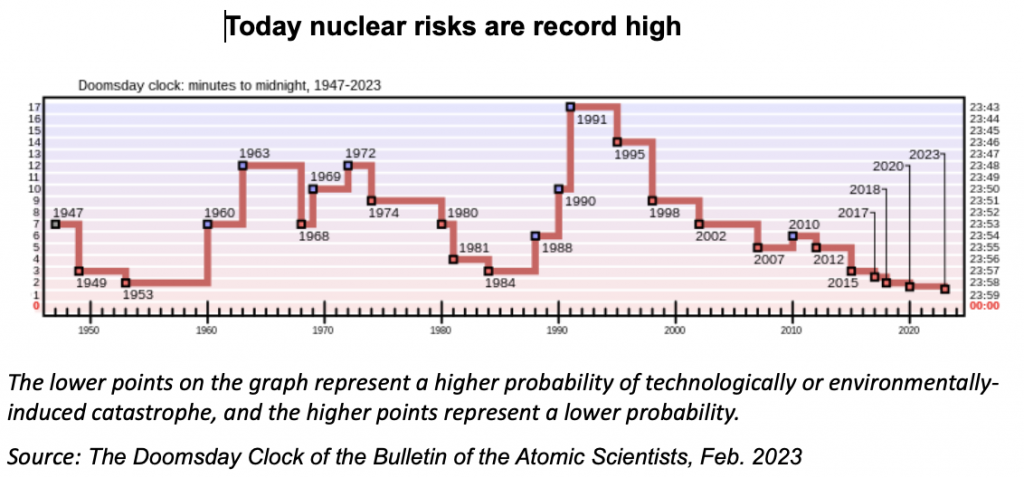

In brief, the very same nuclearization that has caused the global risk of nuclear confrontation to be the highest since 1945, according to US estimates, is now being extended from Ukraine to Asia, including the Philippines. Notice that these nuclear risks have increased hand in hand with the NATO’s eastward expansion since the 1990s (Figure).

Undermined peace

Only a year ago, Ukraine, under Zelensky’s leadership, was still positioned to embrace neutrality, opt out from military alignments and serve as a bridge between Europe and China. Now, all those dreams are in ashes.

Today, the Philippines stands at a similar critical juncture between peace and development – and conflict and devastation.

The original, long version was published by The Manila Times on February 6, 2023