A Hidden Player: The Significance Of Mongolia In Geopolitics – Analysis

By Matija Šerić

Mongolia is a country that has a unique geographical, demographic, economic and geopolitical position. And it is not favorable at all, at least at first glance. Mongolia has no access to the sea, it is located in the climatically cruelly cold East Asia. It has the lowest population density of any sovereign state in the world: two inhabitants per square kilometer.

Its three million inhabitants live in an area the size of Alaska (1.5 million square km), and it is surrounded by 133 million Russians in the north and 1.4 billion Chinese in the south. Although all the above factors greatly limit the economic development of Mongolia, it nevertheless has the best cashmere in the world, a huge potential for eco and cultural tourism, and possesses huge mineral resources: copper, gold, coal, molybdenum, fluorite, uranium, tin and tungsten.

Mongolia is actually an enclave between the superpowers of Russia and China. It is currently a democratic enclave surrounded by autocracies. It is this fact, apart from its harmful effects, that gives this country an important and potentially decisive importance in international relations. Hypothetically and in reality, Mongolia can be a crucial geopolitical player that can seriously damage the Russian-Chinese alliance and lead to a split between these two countries, and on the other hand, it can become a key American partner in the challenging Far East region.

Mongolia has a rich history dating back to the founding of the famous Mongol Empire (1206-1368) and Genghis Khan, who created the largest land empire in history. Historians believe that this is a ruler who was the creator of the Mongolian nation, respected the rule of law, protected religious freedom, promoted international trade and established new diplomatic relations between Asia and Europe. The Mongol Empire connected the previously disconnected world by creating “a unique intercontinental system of communication, trade, technology and politics”.

Genghis Khan shook the world and created a new world order. After his death, the empire was divided, but it survived in some form until the occupation by the Chinese Qing dynasty, which lasted from 1691 to 1911. Then Mongolia overthrew the local ruler and declared independence. The Kyakhta Treaty of 1915 briefly re-established Chinese control, but Russia helped Mongolia finally break free from Chinese rule after the October Revolution of 1917. Mongolia declared independence in 1921. The Soviet Red Army was stationed in the country, and the Soviet Union used Mongolia as a a satellite communist state and a buffer zone with China. Mongolia maintained good relations with both China and the Soviet Union until the Sino-Soviet split in the 1950s. The Soviets had six military divisions in Mongolia, which Russia kept there until December 1992.

The disappearance of the USSR led Mongolia to two major problems. The first problem was the severe economic crisis. Trade with the USSR accounted for 40% of Mongolia’s GDP. All gasoline was imported from Russia, 90% of machinery and 50% of consumer goods. As Russia retreated into itself, the Mongolian economy collapsed. The second problem was of an existential nature. Mongolia was truly independent for the first time in modern history. Although Beijing recognized Mongolian independence in 1945, it is no secret that certain Chinese circles still harbor territorial claims against their northern neighbor. Some see Mongolia as part of China’s historical sphere, and Mongolian elites are concerned that younger and more nationalistic Chinese might try to implement annexation. China’s behavior in relation to provinces such as Inner Mongolia, Tibet, Hong Kong and Taiwan is not encouraging.

The area of modern and internationally recognized Mongolia is also called Outer Mongolia, while the area where the Mongolian people live is much larger and includes: the Chinese autonomous province of Inner Mongolia, Dzungaria (the northern half of the Chinese province of Xinjiang), the Russian republics of Buryatia, Tuva and Altai, and Transbaikal region and the Irkutsk region. All the mentioned regions are part of the pan-Mongolian irredentism that aspires to create Greater Mongolia. Such groups are marginal, but they exist.

According to its political structure, Mongolia is a multi-party democratic republic. The president is directly elected, as are the members of parliament by the Grand State Khural. The president appoints the prime minister, and on the proposal of the prime minister, he appoints the cabinet. The Constitution of Mongolia guarantees all possible freedoms, including full freedom of expression and religion. Mongolia has a number of political parties, the largest being the Mongolian People’s Party and the Democratic Party. According to the opinions of professional organizations that study the degree of democratic freedom, such as Freedom House, it is a democratic and free state.

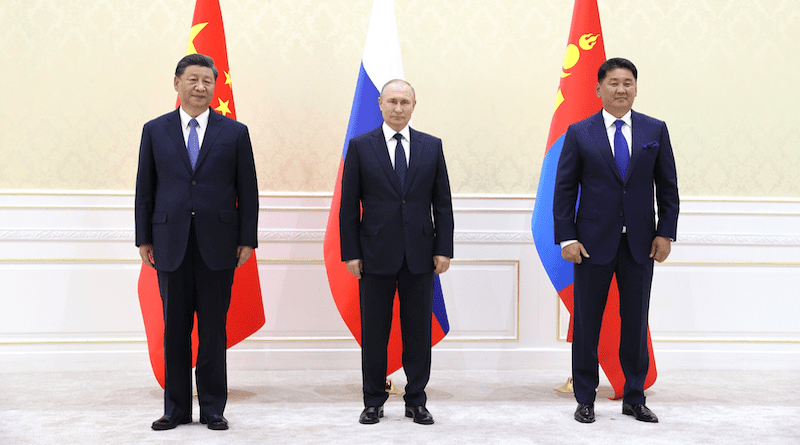

Currently, the president of the republic is Ukhnaagiin Khürelsükh who comes from the left-wing social-democratic Mongolian People’s Party. He won the 2021 presidential election with 72% of the vote and previously served as prime minister from 2017 to 2021. Khürelsükh is a “macho” type of president as he was photographed topless on a Putin-style horse and became known by the nickname “the fist”. after punching an MP in parliament in 2011. However, he has since improved his public image.

After the collapse of the USSR and the Eastern Bloc, the idea of the “end of history” by the American political scientist Francis Fukuyama became popular. In the world, there was great initial enthusiasm for liberal democracy and neoliberal capitalism with one superpower, the USA. Such a situation turned out to be short-lived. Around 2014 at the latest, it became clear that the competition between the superpowers of the USA, Russia and China was in full force. In the chess game of the world’s three most powerful powers, along with many regional powers, Mongolia has an important but largely hidden geopolitical role.

Due to its unique “buffer position” between Russia and China, the protection of sovereignty and territorial integrity is the main priority of contemporary Mongolia. Precisely because of these circumstances, Mongolia’s foreign policy can maneuver between two strategies: the “good neighbor” policy with Russia and China and the “third neighbor” policy in which it strives to build strong ties with other countries – the USA, Japan, North and South Korea , India, European Union countries, Australia and Canada.

In its south, along the Gobi desert, lies the Mongolian border with China. It is interesting that as many as six million Mongolians live in the Chinese province of Inner Mongolia, which is twice as many as in the mother country. China has the most influence on its northern neighbor with its powerful economy. About 80% of all Mongolian exports go to China, mostly coal, copper, unprocessed cashmere. At the same time, more than one third of imports to Mongolia come from China. China is also the largest single foreign investor in the country. Cooperation with China is vital for the Mongolian economy. China relies on the New Silk Road strategic project, that is, on transport infrastructure and commodity trade flows. One of the project’s six transnational corridors would connect China to Eastern Europe via Mongolia and Russian Siberia. The realization of this corridor created an opportunity for Mongolia to export its minerals and would become a regional logistics center. Although the Chinese are rapidly building expensive infrastructure around the world, the project is moving slowly.

The trade war between the US and China directly affects Mongolia. Given that China uses its 80 percent share of global production of rare minerals as a geopolitical tool, Chinese pressure on Mongolia, which is abundant in these resources, is possible. This geo-economic situation makes Mongolia very vulnerable to Chinese economic fluctuations, but it can also be a great advantage. For example In 2017, with the participation of China, Japan and South Korea, the IMF approved a financial package of 5.5 billion dollars for the Mongols, which is the fourth largest financial package in history. The program supports the economic recovery plan and focuses on creating foreign exchange reserves, putting debt within sustainable frameworks, strengthening the banking sector and ensuring stable and long-term growth.

Economic leverage is a powerful tool of Chinese foreign policy that affects other spheres as well. For example In 2016, Beijing closed its borders with Mongolia and imposed import tariffs on Mongolian goods as punishment for a visit by the Dalai Lama. Mongolia has historical ties to Tibetan Buddhism and the Dalai Lama, a title first created by the Mongolian leader Altan Khan in the 16th century. After extracting a promise from Ulaanbaatar not to invite the Dalai Lama in the future, the Chinese Foreign Ministry was overjoyed.

The strongest influence on Mongolia is the Sino-Russian political, economic and military alliance formed by these two superpowers to counter US hegemony. As the Sino-Russian alliance strengthens, it is possible that Mongolia’s value as a token in the geopolitical game will diminish. However, despite the public hype, the Russian-Chinese alliance is not ideal. Moscow still sees Beijing as a potential long-term threat as Chinese claims to Russian territories persist. Russia is concerned that if its 3,485-kilometer border with Mongolia falls under Chinese control, its Siberian bottom will be exposed to a potential Chinese attack.

To counter such ideas, the Russians prioritize balancing Chinese influence in Mongolia by trying to strengthen their economic ties. Undoubtedly, the Russians have a strong influence over the Mongolian economy. Russia supplies about 80% of Mongolia’s oil market, since 2017 trade has increased by almost 40%, Moscow owns a 51% stake in Mongolian railways. In 2019, the two countries announced a strategic partnership that includes a $1.5 billion infrastructure investment fund, an upgrade of the Trans-Mongolian railway, and the possible passage of a Russian-Chinese gas pipeline through Mongolian territory. Russian influence is also present in other areas. Remnants of the Soviet era are visible through the most casual stroll through Ulaanbaatar, which reveals the enduring cultural legacy of Soviet rule, from the Opera House to the Wedding Palace to the Zaisan Memorial. At the same time, Russian territorial ambitions elsewhere on the globe (Ukraine, Kuril Islands) worry Ulaanbaatar because of their potential to strengthen China’s arguments for a potential invasion of Mongolia.

In order to break their dependence on Russia and China and assert themselves as a nation, the Mongols began to increasingly accept the aforementioned “third neighbor” policy – to connect with countries in the region and the world with which they do not directly border. Through strong relations with democratic and non-democratic countries such as the USA, Japan, North and South Korea, India; Mongolia works to strengthen stability and cooperation in Asia. It is rich in uranium but supports nuclear non-proliferation and peaceful resolution of disputes in the region.

Accordingly, the Mongols balance diplomatic ties with North and South Korea and seek to promote stability on the Korean Peninsula. Mongolia describes the United States as its “most important” third neighbor and uses this relationship with Washington to influence political processes globally. Mongolia constantly participates in global peacekeeping operations of the United Nations (about 10 percent of the Mongolian armed forces serve in UN peacekeeping missions). The interoperability and capacity of the Mongolian military have been strengthened through engagement in campaigns in Afghanistan, Iraq and Kosovo. Khaan military exercises are held in the country almost every year in the summer, simulating UN peacekeeping operations in which contingents from numerous countries participate.

Since Mongolia’s location is strategically important in geopolitics, the United States has broader interests in that country. These interests include trade, investments, preservation of democracy and sovereignty, non-proliferation of nuclear weapons, maintenance of peace in the region. What the United States wants most is the survival of Mongolia as a sovereign, independent and prosperous country that plays a constructive role in the region and beyond. This is not strange, since Ulaanbaatar is in the arms of two Americans, perhaps not “mortal enemies”, but certainly two of the biggest rivals in the world. In recent years, the desire to spread democracy in the foreign policy of the USA has fallen to low branches, which also applies to the Far East (the bitter experience of Myanmar). However, US defense and security strategies are closely linked to superpower competition and provide an opportunity to support small states.

American policymakers have interests in the Far East that favor Mongolia, and they are essentially the same under Trump and Biden. It is that the United States is trying to use every means to loosen the Russia-China alliance, is strategically positioning itself towards the Indo-Pacific region, and is trying to achieve the denuclearization of North Korea. Mongolia can be a point of contention between the Russians and the Chinese, and it is also very important because of its influence in the Indo-Pacific region. Ulaanbaatar has excellent relations with Pyongyang and can facilitate peace talks between North Korea and the US.

Ulaanbaatar and Washington also support common goals and values in partnerships on the international scene. For example, Mongolia chaired the US-backed Community of Democracies, an intergovernmental organization based in Warsaw that advocates shared democratic values. The two countries also cooperated in the ASEAN Regional Forum. At the United Nations, Mongolia has proven to be a reliable US ally, consistently voting with the US on General Assembly resolutions. In addition, Mongolia has won America’s favor by implementing UN Security Council sanctions targeting North Korea’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs.

The alliance with the US influences Mongolia to prioritize the policy of the third neighbor at the expense of the policy of the good neighbor. In particular, Mongolia has resisted becoming a full member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), which is led by Moscow and Beijing, in part because of the signal it could send to Washington and other Western capitals. Similar considerations influence Ulaanbaatar’s participation in China’s New Silk Road initiative. By strengthening ties with the US, Mongolia can stand up to powerful neighbors and chart its own foreign policy direction.

In the end, although it may sound contradictory, it is true: the biggest guarantors of Mongolian sovereignty and influence in the region are Russia and the USA. Russia, due to its fear of China, has a permanent interest in an independent Mongolia. Russia’s current strategic control over Mongolia’s energy and transportation sectors makes Mongolia a powerful deterrent to potential Chinese threats. Along with good relations with Russia, the alliance with America and allies in the Indo-Pacific also represent a strategic tool that will repel potential Chinese aspirations.

After nearly seven decades as a satellite state of the USSR, Mongolia made a peaceful transition to democracy and free markets. It currently plays an important role in a new chapter of world history in the 21st century. Mongolia can once again become an influential state through the application of freedoms and the rule of law, participation in international trade, and active diplomatic engagement among feuding states. Not only can it help the reconciliation of the two Koreas, but also the relaxation of relations between the superpowers, especially after the deterioration of relations between Russia and the USA because of Ukrainian crisis.