Debdou, The Moroccan City Of Enlightened Judaism – Analysis

Debdou is a small town in Morocco, and its Jewish community has a long and rich history dating back to ancient times. Over the centuries, the Jewish community in Debdou faced many challenges, including persecution and forced migration, but also experienced periods of peace and prosperity. During the 20th century, many Jews from Debdou and other parts of Morocco emigrated to Israel, Europe, and the Americas, leading to a decline in the size of the community.

The city

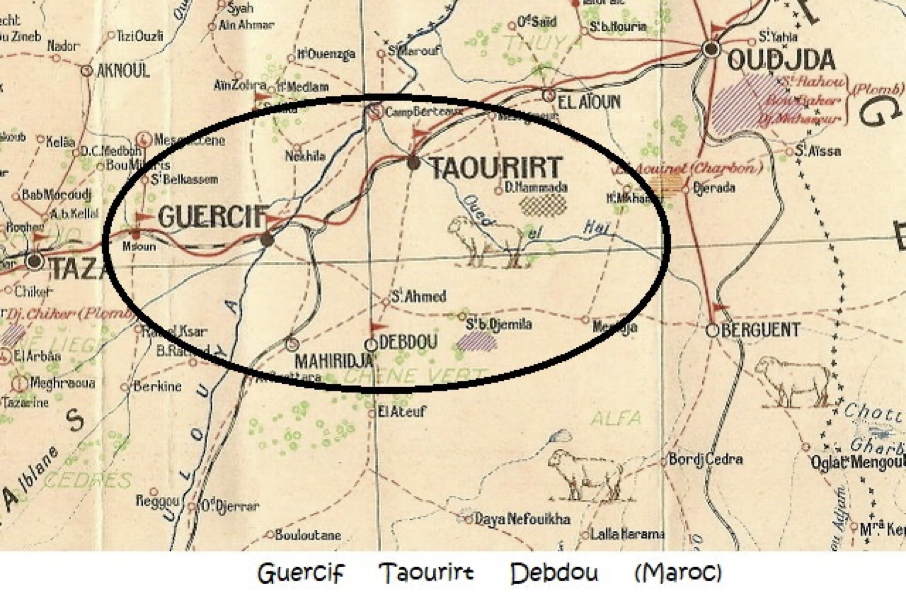

From a physical and structural point of view, Debdou is located at 33° 59′ 9N of latitude and 3° 3′ 4W of longitude at 957 meters of altitude in an enclavement at the foot of the right flank of the valley of Oued Debdou (tributary of the Moulouya) which rises in a perpendicular wall at 80 meters above the bottom surrounded by massifs, blocking the road to the fertile plains of northern Morocco, including that of Tafrata and Sedja, which are unavoidable because a secondary road (No. 410), connects it with the main cities of the north of the region, including Taourirt 53 km north. The latter extends further east to the Jerada mountains and west to Guercif and Taza.

The massifs constituting the surroundings of Debdou are: the mounts Zekkara, Beni Yala, Beni Bou, Zeggou, Gaâda or plateau of Debdou (1615 meters) which has pronounced projections and fall in a cliff and whose slope is marked by the presence of many pines and holm oaks, junipers whose anthropic origin is noticed by the organization in parallel bands of the forest massif, also a cordon of oleanders and a wadi specify the thalweg.

Debdou (in Arabic دبدو, and in Amazigh ⴷⴻⴱⴷⵓ) is a city and a commune – Moroccan municipality – in the province of Taourirt, in the Eastern Rif region. (1) Debdou is a small town in the Moroccan Oriental region, located 180 km from the Mediterranean, 150 km from the city of Oujda, capital of the Oriental region, and 53 km south of Taourirt, the capital of the province.

The assets of this city are multiple:

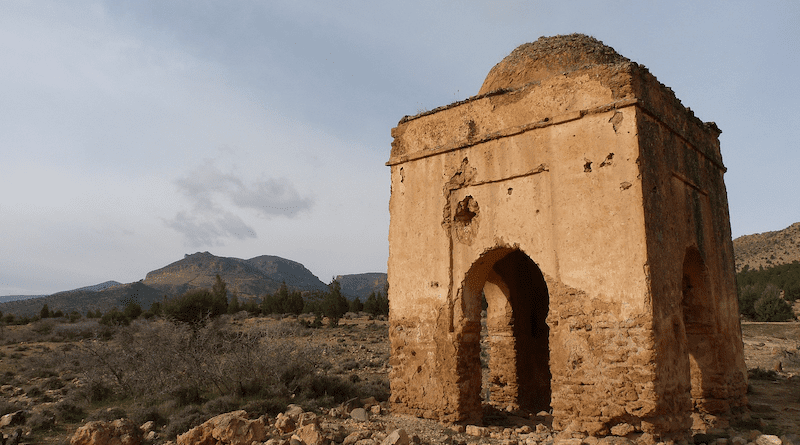

- A very rich past and history, as evidenced by the monuments still standing;

- A city known to be one of the few to have sheltered one of the most important Jewish communities of the Maghreb, until the first half of the 20th century. Debdou is known, also, for having been an example of peaceful coexistence between Jews and Muslims;

- Ancestral traditions jealously maintained, and;

- A fabulous geographical site.

Unknown and forgotten today, Debdou was, however, during several centuries a prosperous emirate which took part in the building of contemporary Morocco. It was a Marinid (1244-1465) city in the 12th century, and played a very important political role between the 13th and 16th centuries.

From an administrative point of view, Debdou is located in the south of the Oriental region, and more precisely in the province of Taourirt included in the Wilaya of Oujda: province created by the decree of April 9, 1997, following the division of the former region of the province Berkane-Taourirt, with the annexation of the Debdou circle (locality) belonging to the province of Jérada. The province of Taourirt covers an area of 8541 km2, with a population of 180,000 inhabitants, 106,000 of whom live in urban areas, and includes 3 municipalities and 3 circles with 11 rural communes.

The urban structure is divided into three levels starting from the historic center and annexed developments:

- On the right side of the valley at the upper level there is the source of Tafrant tourist place recently developed with several cottages. It is a place close to nature, and its tourist importance has been growing for some years. On a neighboring plateau stands the Marinid kasbah known as ‘’Caïd Ghomriche’’ dating from the thirteenth century whose site is classified as World Heritage by UNESCO and is the subject of archaeological research.

- The second is constituted around the Mellah below the valley, it is here around the “big street” leaving the main road that we find the Wilaya center which is noticed by the presence of warehouses and stores and thus of an important activity, and by which transit the main flows of human and commercial traffic. All around it, a more or less dense built-up area has developed, whose development seems to be in continuity with the center.

- The discontinuity characterizing the third part of the city on the “periphery” are the douars (group of houses). It is a part characterized by its identity particularities rather strong by its antiquity, indeed it is noticed by the presence of old clay buildings (red color) or adobe, and it is quite fragmented into different neighborhoods or localities, most of which are located on mountainous slopes or hills and are (for some) in disuse, eg: Lamssalla, Bou Ayach, Khelifit, and Oulad Choui.

- To this, one can add a fourth more recent part corresponding to the more or less anarchic development of the city, including in particular the districts of Khor, and Haouch. The latter have just been attached to the city center and have a sewerage system.

As far as the economy of Debdou is concerned, it is organized around a traditional irrigated culture around the city, the craft industry as well as the breeding of sheep, cattle, and poultry. It benefits from a fauna, and especially from a rich flora which gives it certain advantages in particular the rosemary very appreciated for the manufacture of essential oils, and the esparto.

However, one notices that the physical organization of the space around this city makes it partially isolated from the rest of the region, which means that in a way from a geographical point of view, it can be linked to the spaces of the Eastern Highlands even if its opening to the North tends to reduce this effect. Thus, there is an effective polarization with the North and the East, which can be seen in the presence of bus lines and cabs making the daily trip between Debdou and Taourirt and westward to Guercif, and Taza.

The relationship between Debdou and Taourirt is all the more important in terms of human and product flows since it is the largest city to be directly linked to Debdou, which has outlets, particularly for its fodder production, and its flock of sheep, goats, cattle (197 990 heads in 2005), a consequence that must be linked to the first sheep souk and national livestock exchange of the country, similarly, it also constitutes outlets for the pastoral economy of the highlands of the south of the east. It is important, also, to note that Debdou has long been located on the passage of Saharan tribes to Taza which are now largely sedentary as the Zouas.

In addition, it should be noted the presence of the weekly souk on Wednesdays, which is used to purchase domestic necessities such as food products (e.g. fruits and vegetables), laundry, textiles and hardware or other materials that feed the local crafts such as scrap metal (for the manufacture of doors, window grills, balconies, and railings), wood, not to mention construction materials in the building sector under the impetus of the RME (Moroccans residing abroad). There are, also, government administrative buildings, military barracks further north, and household equipment stores that sell televisions, satellite dishes, washing machines, refrigerators, and computers.

Debdou is located on the outskirts of the main axes of the regional economy without, however, being far from them by constituting a transition zone with the less dynamic south, that is to say “the periphery of the periphery”. Indeed, its endowment with equipment in a relatively isolated and poor area of the region has raised it to the chief place of the circle, it now has broader long-term claims to the rank of provincial capital as its sister Taourirt has, but next to which it still looks like a little stroller.

Population

Traditionally the region of Debdou is inhabited by 3 large tribes: (2)

- Beni Merines: this is the original tribe of the Marinid dynasty which dominated Morocco and part of Algeria between 1244 and 1465.

- Beni Ghoumrassen: there remains a fraction of this ancient tribe within the Beni Guil tribe.

- The Jewish tribes: a large Jewish community originally made up of families who left Andalusia in 1391, and formed several tribes that inhabited the area until the 1960s.

At the end of the 19th century, Ahl Debdou rallied to the throne pretender Rogui Bou Hmara (1860-1909) (3) at the expense of the Alouite Sultan Moulay Abdelaziz (1881-1943).

Nahum Sloushz introduced this city in the following term: (4)

[“Of very ancient foundation, Debdou played an important role in the history of Morocco, occupying a strategic place between Fez and Tlemcen which made it the stake of dynastic struggles. When Abd Al Hakk (1196-1218) distributed it among the Merinid tribes, it fell to the Berber Banu Urtajjen who, in charge of covering Fez against the undertakings of the Abd Al Wadides of Tlemcen, made it the capital of their fiefdom; this led to it being devastated in 1364-5 by the king of Tlemcen. However, around 1430, one of the chiefs of the Banu Urtajjen succeeded in founding a small principality in Debdou, whose lords kept their independence from the Wattassids and even competed with the project in 1499 to seize Taza; this small state only disappeared under the second soand vereign Sa’id Al Gahlib-Billah, who in 1563 placed its territory under the authority of a pasha. From then on, the history of the city, rather obscure, was reduced to local conflicts between Arabs and Berbers. Nevertheless, in the 19th century, Debdou still enjoyed an autonomous administration; the Muslim population depended on the ‘amil of Taza, which sent its khalifat to collect taxes, while the Jews paid their tribute to the pasha of Fez. At the end of the century after the advent of Mawlay ‘Abd Al Aziz (1894) and during the revolt of the pretender Bu Hamra a Berber named Bu Hasira tried to make himself independent; but in 1904, the city and its surroundings rallied to Bu Hamra, at the instigation of the Jew named Dudu B. Hayda who was appointed caïd. Hayda, who was appointed as mayor of Debdou and took advantage of this circumstance to take reprisals against his enemies, the Jews of Andalusian origin.’’]

‘’De fondation très ancienne, Debdou a joué un rôle important dans l’histoire du Maroc, occupant une place stratégique entre Fès et Tlemcen qui a fait d’elle l’enjeu de luttes dynastiques. Lors de la répartition effectuée par Abd Al Hakk (1196-1218) entre les tribus Mérinides, elle échut au partage aux berbères Banu Urtajjen qui, chargés de couvrir Fès contre les entreprises des Abd Al Wadides de Tlemcen, en firent la capitale de leur fief ; cela lui valut d’être dévastée en 1364-5 par le roi de Tlemcen. Cependant vers 1430, un des chefs des Banu Urtajjen réussit à fonder à Debdou une petite principauté dont les seigneurs conservèrent leur indépendance à l’égard des Wattassides et concurrencèrent même le projet en 1499 de s’emparer de Taza ; ce petit État ne disparut que sous le deuxième souverain Sa’id Al Gahlib- Bi-llah qui en 1563 plaça son territoire sous l’autorité d’un pasha. A partir de ce moment, l’histoire de la ville, plutôt obscure se réduit à des conflits locaux entre arabes et berbères. Il n’en reste pas moins qu’au XIX ème siècle, Debdou jouissait encore d’une administration autonome ; la population musulmane dépendant du ‘amil de Taza, qui envoyait son khalifat percevoir l’impôt, tandis que les juifs remettaient leur tribut au pasha de Fès. A la fin du siècle après l’avènement de Mawlay ‘Abd Al Aziz (1894) et durant la révolte du prétendant Bu Hamra un berbère nommé Bu Hasira essaya de s’y rendre indépendant ; mais en 1904, la ville et ses environs se rallièrent à Bu Hamra, à l’instigation du juif du nom de Dudu B. Hayda qui fut nommé caïd de Debdou et profita de cette circonstance pour exercer des représailles contres ses ennemis, les juifs d’origine andalous.’’

According to an article in the Encyclopedia of Islam, (5) “Debdou” (in Arabic دبدو) is the most common spelling designating this small town in eastern Morocco, it can also be written Dabdū. Similarly, one calls an inhabitant of Debdou a Debdoubi or Debdoubia, giving the plural Dbadba. (6)

Historically, there are three hypotheses for the origin of this name:

- The first is related to the coming of the Jews in the 14th century and in particular of one called David Dou (it is in fact Rabbi David Ha-Kohen);

- The second, more likely, is related to the first inhabitants of the region, the names of Debdou being close to an Amazigh term meaning ‘’funnel’’, and;

- The third is related to the occupation of the Marinids with the same meaning as before, in any case Debdou is mentioned in the texts only from the 18th century.

This city has a glorious past. It was a Jewish city par excellence, inhabited by Jews coming from Spain, during the conquest of this country by the Arabs. “Debdou la Juive” as it was called in the 16th century occupied a great place in the Jewish intellectual movement of the 15th and 16th centuries. (7) Several rabbis, by their science as well religious as profane, illustrated this time which was a glorious moment in the history of Moroccan Judaism. (8)

On the subject of the population of Debdou, C. El Briga writes in the Encyclopédie berbère: (9)

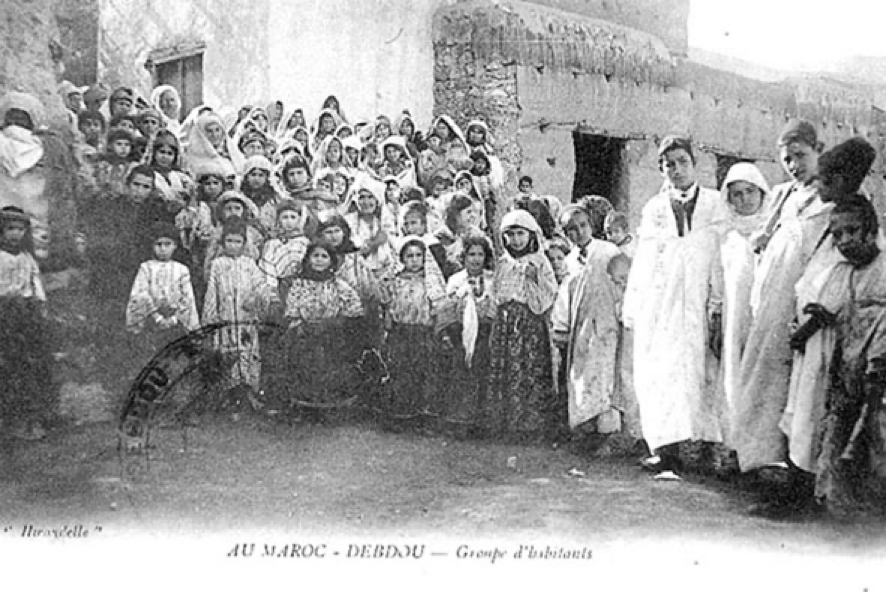

[‘’Debdou was one of the few cities in the Maghreb where the Jewish population outnumbered the Muslims; in 1910 it was 1,310 strong while the Muslims numbered 1,200. However, the Jewish community of Debdou gradually lost its importance, and in 1936 it numbered only 917 people out of 3,000 inhabitants. This decline was mainly due to the commercial decline of Debdou, which faced competition in the north from Guercif (5,600 inhabitants) and Taourirt (7,500 inhabitants), both of which were served by the railroad, although in 1950 the track from Taourirt to Debdou was not yet paved. In the south, the creation of new commercial centers, such as Missour, attracted merchants and services. Today the Jewish community has almost completely disappeared and the population of Debdou does not exceed 4,000 to 5,000 people, almost all of whom are Arabic-speaking, the Berber-speakers surviving only in the mountains of the Gada.’’]

‘’Debdou était l’une des rares villes du Maghreb où la population juive était plus nombreuse que les musulmans ; en 1910 elle était forte de 1 310 personnes alors que les musulmans étaient au nombre de 1 200. La communauté juive de Debdou perdit cependant progressivement de son importance, ainsi elle ne comptait plus que 917 personnes sur 3 000 habitants, en 1936. Cette chute s’explique essentiellement par le déclin commercial de Debdou qui fut concurrencé, au Nord, par Guercif (5 600 habitants) et Taourirt (7 500 habitants) tous deux desservis par le chemin de fer alors qu’en 1950 la piste de Taourirt à Debdou n’était pas encore bitumée. Au Sud, la création de nouveaux centres commerciaux, comme Missour attirèrent les commerçants et les services. Aujourd’hui la communauté juive a presque complètement disparu et la population de Debdou ne dépasse pas 4 000 à 5 000 personnes presque tous arabophones, les berbérophones ne subsistent que dans les montagnes de la Gada.’’

The history of Debdou

Debdou is located in north-eastern Morocco in a mountainous landscape, off the roads that connect western Morocco to Algeria. The origin of the Jewish community in this locality dates back to the Almohad (1121-1269) or th Marinid period. To the indigenous Jews (Toshavim), were added Jews expelled from Spain (Megorashim) during the anti-Jewish riots of 1391 in the Crown of Aragon. (10)

On this point, Abner Darmon writes: (11)

[‘’ Most of the Jews of Debdou came from Spain. Among them, some, the largest number, come from Murcia (Oulad Marciano), others from Seville – the spring that feeds Debdou still bears the name “Aïn Sevilla”. After having wandered in the mountains of the Rif and on the Moroccan coast, they ended up forming a large community in Debdou.’’]

‘’La plupart des Juifs de Debdou sont originaires d’Espagne. Parmi eux, les uns, le plus grand nombre, viennent de Murcie (Oulad Marciano) les autres de Séville – la source qui alimente Debdou porte encore le nom de « Aïn Sevilla » – Tous sont des exilés, échappés vers la fin du XIVe siècle aux massacres de l’Inquisition espagnole. Après avoir erré dans les montagnes du Rif et sur la côte marocaine, ils ont fini par former, à Debdou, une communauté importante.’’

Debdou is proud to have been able to maintain this intense religious focus despite the numerous persecutions. (12) This small town has had the honor of having given birth to a good number of rabbis whose fame spread all over North Africa, the most revered of whom, and the worthiest of general admiration, are: Rabbi Chelomo Cohen, President of the Rabbinical Tribunal of Mazagan, and Rabbi Bensoussan Aziz, President of the Rabbinical Tribunal of Mogador. (13)

The Jewish quarter of Debdou was built near a spring considered to be miraculous because it was said to have sprung up following the prayers of one of the exiles, Rabbi David Hacohen, leader of the community.

The Spanish connotation of this city continued for several centuries as it was called Seville within the community. The city reached its peak in the 17th and 18th centuries, although the French conquest of neighboring Algeria in 1830 shifted trade to Tlemcen. (14)

The city had a rabbinical court and the yeshivah of Debdou attracted many students; judges and ritual slaughterers, from other communities, who came here for training.

However, the plague epidemic of 1818-20 (15) decimated the Jewish population and in the 19th century, the Jews of Debdou were placed under the protection of the Pasha of Fez. In 1897 and again in 1904, Debdou benefited from food aid from the Central Committee of the Alliance Israélite Universelle due to the threat of famine caused by drought, locusts and the strong tensions in Morocco during these years of crisis. (16)

But the insecurity in the region continued until the French occupation in 1911. At that time, Debdou had 50% Jews – half of whom were Cohanim – out of a population of 4000 inhabitants and more than a dozen synagogues. Most of the inhabitants practiced the trades of jewelry, weaving, embroidery, leatherwork, and animal husbandry. (17)

Throughout the history of the city, some Jews benefited from good fortune, which went as far as the exercise of political powers, such as the Jew Aaron ben Mchcal, who, in the middle of the seventeenth century, gained suzerainty over the former stronghold of the kings of Debdou: a kasbah that, according to a Jewish chronicler, “he governed like a king “. (18) More recently, the rebel leader Bou Hmara had not hesitated to appoint David Cohen Saqali, who had rendered him “notable services,” “caïd without seal of the whole square of Debdou, ” (19) with authority over the Muslim populations of the city. Several Jewish families in Debdou owned agricultural properties in the immediate vicinity of the city.

Like their co-religionists in Morocco, the Jews of Debdou are involved in complex political games in which they are rarely in a position of strength, but which cannot be reduced to a litany of persecutions.

Following the creation of the State of Israel and after the independence of Morocco in 1956, the inhabitants of Debdou emigrated to the cities of the interior, i.e. Casablanca, Rabat, and Marrakesh, and, also, to France, and Israel. Among the figures who marked the history of the Jewish community of Debdou are: Rabbi Abraham BenSoussan, Rabbi Yossef Cohen-Scali, Rabbi David Hacohen and Rabbi Chlomo Hacohen. (20)

The Kings of Debdou

Moussa Ben Hammou announced the dynasty of what can be called the “Kings of Debdou” whose list is known by Leo Africanus (1494-1554). (21) This is a period that marked the apogee of Debdou in history. This period is linked by oral tradition to the Marinid dynasty although it is later. Thus Nahum Slouschz specifies that not much is known about the origin of this ruler, apart from the fact that a Jewish clan bears his name, as do the Oulad Hammou among the Ahl Admer in the region surrounding Réchida further west. (22)

Here are their names and dates of reign in chronological order, it is a hereditary dynasty that was recognized as a dynasty of Shorfa: (23)

- Moussa Ben Hammou (1430-1460);

- Ahmed (1460-1485);

- Mohamed Ben Ahmed (1485-1513), nicknamed “the King of Debdou”;

- Mohamed II (1513-1550), and;

- Ammar (1550-1563).

The reign of these rulers is linked to the weakness of the central authority after the fall of the Marinids under the Wattasids dynasty (1472-1554), and the Saadis (1549-1659).

Debdou took advantage of this dynastic weakness and knew its apogee under the reign of Mohamed Ben Ahmed (1485-1513), the latter being considered as the most prestigious sovereign of his family, hence his nickname “the King of Debdou”. He embellished the city with some buildings such as the al-Kasbah and the big mosque. He, also, wanted to take control of Taza at the request of the inhabitants of this city. But the Saadi Sultan Mohammed Esh-Sheikh (1490-1559) opposed it and went to make the siege of Debdou, which was forced to submit. The latter nevertheless remained full of respect for him and entrusted him with what became the viceroyalty of Debdou. (24)

After these events, the kings of Debdou remained subject to the Beni Wattas (1472-1554) and to the dynasty of the Saadi Shorfas who succeeded him while keeping a great autonomy, especially concerning the internal affairs of Debdou, which is one of the permanent features that can be noted throughout its history even after its decline until the arrival of the Rogui Bou Hamra and the French five centuries later.

Debdou, land of immigration

A series of socio-economic factors have allowed Debdou to maintain relative importance as the “port of the Orano-Moroccan steppes”. The place occupied by the Jews at this level has been decisive. Chronologically speaking, it is true that they could have been included from the reign of Mohammed Ben Ahmed, but the role that this community played in the history of Debdou was to take on its full importance in the centuries that followed. (25)

Thus, in the first place, the Jews expelled from Seville who came from Tlemcen. Another embryo from Tlemcen would have come around 1545 following the conquest of Tlemcen by the Ottoman Khar ad-Dine Barberousse (1476- 1546) (26) according to Rabbi David Hacohen in his Responsa book whose content proves that the presence of the Jews goes back at least to the 16th century.

The arrival of this community was therefore in a rather troubled context since it corresponded to the incursions of the Ottoman Turks in the region. Here again, Debdou occupied a strategic position both for the Ottomans and for the Europeans. Indeed, Debdou is located at the borders of the “Sublime Porte” occupying the region of Tlemcen at the gates of the Sherifian empire which touches Spain. A long and complex war began between these two empires ending in the Triumph of the Sherifian Empire and thus keeping the Ottomans at bay.

Even after these events Debdou still held an important place in regional history. The expulsion of the Jews and Muslims from Spain, especially from 1391 onwards, brought new blood to Morocco, especially to cities such as Fez, Sefrou, and Debdou, which received colonies of Sephardic Jews. This allowed Debdou to continue to shine for several centuries by boosting its trade, but also from a cultural and religious point of view. Thus, it continued to have an influence that is out of all proportion to its size for several centuries.

The Jewish Tribes of Debdou (see Annex I for their names)

The Jews of Debdou, just like their Muslim neighbors, split into multitudes of tribes, with antecedents in Djerba as Nahum Sloushz reminds us. This favored local particularisms but especially, as one can imagine, antagonisms between them. It is through latent and persistent conflicts through the centuries opposing the two large local groups that are the Morciano (or Marciano) and the Saqali (or Sqali) that these are revealed. The more or less legendary origins attributed to these tribes as well as their seniority in Debdou play a particular role, notably through the influence they had within the other tribes. (27)

Thus, for example, Nahum speaks of the etymology of the name Saqali, questioning the ancient and sacred origin claimed by the Cohen Saqali (although theoretically outside the conflicts, this can lead to confusion). The same goes for the Saqali who reproach the Morcianos for refusing to recognize the Saqali’s right of priority over the Mellah when they were expelled from the Dar Machcal. The latter consider them as intruders in Debdou because the Morciano, unlike the Saqali, resided in Tatsidalt, i.e. the Kasbah al-Makhzen before living in Debdou.

These tribes emigrated because of the insecurity that prevailed during the period of instability between the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. A certain number of families left Debdou and went to settle in Taourirt and Berguent, or in the other stations created by the French military authorities: they are attracted there by greater security. Other families stayed elsewhere than in Debdou while maintaining ties (family, and commercial), especially in the large cities of Morocco and Algeria. By 1950, the Mellah was already abandoned and by the end of the 1970s there were no longer any Jews living in Debdou.

The population of Debdou was mainly composed of Jews at the beginning of the 20th century according to Nahum Slouchz: (28)

“The population of Debdou presents a curious fact: the Israelites form three quarters of it; on approximately 2000 inhabitants, they are 1500. It is the only place in Morocco where the number of Jews exceeds the number of Muslims.’’

The author admits later that he is exaggerating a little, and that there are other localities where the Jews form almost the totality of the population), the first traces of their presence in Debdou goes back to the 14th century. At that time, a series of persecutions hit Spanish Judaism with a brutality unknown until then, culminating in 1391.

Debdou is mentioned in the texts only from the 13th century as being a fortified place. As for the Mellah, it must date back to the 16th and 17th centuries. Is it reasonable to say that Debdou was a real ethnic dig? Insofar as one is going to see that at the scale of a douar one finds 4 or 5 different strains. Thus, Michel Lecomte (29) notes the absence of elements that could be considered as indigenous, which is the sign of a rich history and a past prosperous enough to attract all these people, showing that in the past Debdou was a frequented route for trade and pilgrimage. There was even talk of the “Trîq as-Sultân“. (30) It was also used for fighting. Debdou must have been a sort of refuge for the populations. This observation leads one to ask a question: before the arrival of these inhabitants, who was there? Did Debdou exist?

Visiting Debdou, a young French soldier of 26 years of age described the Jewish people of the city in the following friendly terms: (31)

[‘’What strikes the foreigner above all, as soon as he enters the slippery and tortuous gutters of the Mellah, is the decent dress, the air full of dignity and correctness with which the Jews know how to welcome him. Hospitable, as we said earlier, despite a certain reserve, they have a speech and manners that contrast with the coarse and savage personality of the local mountain people. One can say – and all those who have approached them will agree – that they have, in spite of the effect of the barbaric rudeness of their former persecutors, preserved their patriarchal mores which give the father all the rights but also all the duties.

The exile and the persecution, instead of extinguishing in them any feeling of dignity, could on the contrary, and it is there a psychological phenomenon known in the history of humanity, only to tighten them more in the same feeling of intimate solidarity; the religious unity which always dominated among them the known dissensions of the families and the clans, confuses them all in the same thought, in the same belief: the unshakeable faith in a unique and universal God, faith that a long martyrology could only exalt and strengthen.’’]

‘’Ce qui frappe surtout l’étranger, dès qu’il s’engage dans les boyaux glissants et tortueux du Mellah, c’est la tenue décente, l’air plein de dignité et de correction avec lequel les Juifs savent l’accueillir. Hospitaliers, ainsi que nous le disions plus haut, malgré une certaine réserve, ils ont un parler et des manières qui font opposition avec la personnalité grossière et sauvage du montagnard des environs. On peut dire – et tous ceux qui les ont approchés en conviendront – qu’ils ont, malgré l’effet de la rudesse barbare de leurs anciens persécuteurs, conservé leurs mœurs patriarcales qui donnent au père tous les droits mais aussi tous les devoirs.

40L’exil et la persécution, au lieu d’éteindre en eux tout sentiment de dignité, n’a pu au contraire, et c’est là un phénomène psychologique connu dans l’histoire de l’humanité, que les resserrer davantage dans un même sentiment de solidarité intime ; l’unité religieuse qui a toujours dominé chez eux les dissensions connues des familles et des clans, les confond tous dans une même pensée, dans une même croyance : la foi inébranlable en un Dieu unique et universel, foi qu’un long martyrologe n’a pu qu’exalter et raffermir.’’

The miracle of Debdou

A city known for being one of the few to have sheltered one of the most important Jewish communities of the Maghreb, until the end of the 19th century. Debdou is known for having been an example of peaceful coexistence between Jews and Muslims.

The city of the exiles from Seville, known as the city of the cohanim כֹּהֲנִים (priests) or the city of the soferim מסכת (scribes) is the abode of great families that made up its community: the Cohen Scali, the Marciano, the Benhamou, the Bensoussan, the Benguigui, the Marelli, the Sultan, and many others. (32)

A small group of refugees from Seville arrived in Debdou. The local tradition speaks of a dozen families, mostly cohanim, seeking a place of asylum under the leadership of Rabbi David Hacohen. But there was a lack of water, it is said. Rabbi David, after fervent prayers, struck the rock with his staff, and a spring sprang up that is still known today as cAyn Sbilya, the Spring of Seville.

It was near this spring that the Jewish quarter of Debdou was built, which has had a long history up to the present day. It should be noted in passing that, according to the recent testimony of several visitors, this legendary spring gradually dried up after the Jews of Debdou left the town in the years following Morocco’s independence.

Written documents confirm the oral tradition about the origins of the community. For example, Rabbi Yosef Cohen-Scali wrote to the rabbis of Fez: “Know that nearly a hundred years ago our ancestors (cohanim) left Seville…“, (33) or this text among many others: “…and the community of Seville which is in Debdou follows the minhag (custom) of the megurashim (exiles)…”. (34) But what better testimony to the Spanish origins and the attachment to the ancestral heritage than this document dating from 5481-1721: “It is well known that the synagogue of the city of Seville (sic), overlooking the main street to the east and adjoining the property of Rabbi Yossef Hacohen-Scali to the north, and which is called the Sabban Synagogue…”. (35) Thus, Debdou the Moroccan had simply become, in the official documents of its Jewish community, a new Seville in Muslim lands! (36) To attribute a new name to the host locality seems to have been a widespread phenomenon in Spanish Judaism, mentioned by Don Isaac Abravanel – “The Abarbanel” (1437–1508) (37) at the end of his commentary on Melakhim-Rois.

On this particular point, Lhaj Mohamed Nacik writes in Hesperis Tamuda: (38)

‘’A first wave of Jewish refugees from Catholic Spain arrived in 1391 as a result of the massacre of the Jewish community in Seville. Most of them settled in Debdou, giving the river there the name of Oued Sbila (river of Seville). However, the main influx was after the expulsion of the Jews from Spain and Portugal in 1492. The dispersion of the Jews from the Iberian Peninsula led to the establishment of an international network of whish the Sultans of Morocco were quick to take advantage in extending their diplomatic and commercial relations with Europe. Thus in 1591, under the Saadian dynasty, we first hear of the appointment of a Jew, Simon Pellas, as Moroccan Ambassador to Holland, where he concluded a trade treaty, while his brother, Joseph, was sent as Ambassador to the Court of Elizabeth I, and his son, David, as Ambassador to France in 1636. In the seventeenth and 180 Lhaj Mohamed Nacik eighteenth centuries a number of Jews were accredited to European courts and Morocco was represented at the Court of St. James by Haim Toledano during the reign of Moulay Ismail (1672-1727), by Jacob ben Abraham Benidder, hitherto British Consular Agent in Salé, in 1763 and successively by Mesod Cohen and his son, Meir, during the reign of Moulay Sliman (1792-1822).’’

In the above-mentioned opuscule Yahas Debdou, Rabbi Chlomo Hacohen Sabban writes on this subject:

“The fact that in their documents they attributed to Debdou the name of Seville (…) tells us (…) that it was a question of their perpetuating the name of the city from which they had been expelled, so as not to forget the torments of their exile…”.

It is true that Seville held a special place in the world of Spanish Judaism: the ancient times and the nobility of the Jewish families who lived there were known, and great masters resided there. Thus, for example, the Ritva, Abudarham, and Rabbi Yaacov Ben Acher, (39) author ofthe Arba’ah Turim. (40) The families of the cohanim who came from Jerusalem seemed to preserve the memory of their origins with jealous care, since the Juderia of Seville included alleys inhabited only by cohanim.

It is easy to understand why these same families, constituting the essential element of the community of Debdou, had a particular character: it was in their ranks that most of the spiritual masters of the city were recruited throughout the generations, whose influence often extended to the surrounding area; and the qualities of character of the Jews of Debdou, as well as the particular piety which impregnated their morals, were reputed in Morocco and in Algeria. The families of the cohanim preferred to contract marriages within their midst, without excluding unions with simple “Israel”. It should be noted that, as in Djerba, no family of Levi” was able to settle in Debdou: a Levi” was never allowed to stay more than a year in the city, no doubt for fear of a kind of unfriendly “competition”.

The cohanim of Debdou are commonly called Cohen-Scali, which means “brilliant” cohen, i.e. of pure ancestry. Some explain that the word Scali has the same numerical value as the word Tsadoq: this indicates that the cohanim of Seville and Debdou were descended from the high priest Tsadoq. In his book Otsar Ha- Mikhtavim, (41) Rabbi Yosef Messas (42) explains another tradition concerning the nickname Scali: the clothes of the cohanim in Jerusalem were woven with shining golden threads.

Debdou, the Jewish city of religious knowledge

Nevertheless, the yeshiva of Debdou continued to be a reservoir of talmid Chakhamim תלמיד חכמים(disciples of the wise), dayanim דיין (rabbinic judge), and shohatim, who served in the city itself or in outside communities, even in Algeria.

When the French arrived in Morocco in 1912, Debdou had some four thousand inhabitants, of whom about two thousand were Jews: of this number, at least half were Kohanim כֹּהֲנִי (priests). (43) Of the fifteen or so synagogues and oratories in the city, more than half are attended mostly or exclusively by these descendants of Aharon who, even in the absence of simple “Israel”, pronounce the priestly blessing in chorus: in order, says the Shulhan Arukh, (44) to “bless their brothers who are in the fields“, and because they themselves are included in the blessing anyway.

Several important personalities illustrated the city of Debdou at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th: in the first place, Rabbi Chlomo Hacohen, a strong personality who led his community with wisdom and firmness.

Two of his students held rabbinical positions outside of Debdou: Rabbi Avraham Bensoussan, who was appointed dayan, then president of the rabbinical court of Mogador (Essaouira, today); Rabbi David Hacohen, appointed in 1913 as dayan in Oran, where he ended up leading the rabbinical court. His halakhic responses were published under the name of Kiryat Hana David. A second rabbi, Chlomo Hacohen, who was dayan in Oujda, left numerous manuscripts, and four volumes of Responsa שאלות ותשובות (questions and answers) have been published to date (notably Lekha Chlomo, Vayhal Chlomo, Vayéessof Chlomo, and Maâloth Lichlomo). (45)

The famous Charles de Foucauld, (46) who was later to end his days as a hermit in the Sahara, came to Debdou in 1883. (47) He was an officer at the time and, disguised as a Jew as he traveled through Morocco on behalf of the French intelligence services. In Debdou, he was offered lodging by a Jewish family.

Father Charles de Foucauld stayed there from 1883 to 1884, and it is said that he even learned Arabic and Hebrew there, which allowed him to cross Morocco and to penetrate Arab circles disguised as a rabbi. In his book “Reconnaissance au Maroc“, (48) he noted:

“the population of Debdou presents a curious fact, the Israelites form three quarters of it; on 2000 inhabitants, they are 1500. It is the only place in Morocco where the number of Jews exceeds that of Muslims.’’

The Muslims, however, got wind that a Christian was in the Jewish quarter, and it was only through the dedicated efforts of the community leaders that a catastrophe was averted. The Jewish quarter was nevertheless ransacked shortly after Charles de Foucauld’s hasty departure.

The post-war period, with immigration to Israel, Moroccan independence, and the settlement of many “debdoubis” in France, saw the end of the long history of Debdou, the city of the cohanim, the little Moroccan Seville. The miraculous “spring of Seville”, as was called, suddenly dried up after having supplied the city’s Jews with water for many centuries.

Debdou, Sevilla of North Africa

600 years ago, Jews fled Europe and took refuge in Debdou, a city in the Moroccan East and a land of Islam! At the end of the 14th century, Catholic Spain was going through one of the most troubled periods in its history. In the context of serious economic and social problems, a wave of anti-Jewish persecution overwhelmed the Iberian Peninsula and in particular southern Spain and Andalusia.

Several pogroms took place targeting the Jews of Spain. These events also called bloody baptisms and known in Jewish tradition as the decrees of 5151 (Hebrew: גזירות קנ “אgzeirot kana) result in a series of massacres and forced conversions that had begun in Seville on June 4, 1391 before spreading to much of Andalusia. (50)

With no other choice but to convert to Christianity or die, several thousand Jews took the path of exile and crossed the Mediterranean to find refuge in North Africa. Among them, a group of several Jewish families decided to go into exile in the north of Morocco and settled in the city of Debdou located at the foot of the Atlas Mountains in eastern Morocco. They were called the “Sevillians” of Geros Sbilia. (51)

Legend has it that Rabbi David Hacohen, who led these exiles to the foothills of the Atlas, saw that the town was experiencing a serious water shortage that would handicap the future settlement of the tribe, and struck a rock with his stick, from which a spring sprang up, certainly an Andalusian one, since it was joyful and babbling. This source still exists and it became today, a place of pilgrimage and worship, Debdou always venerates “Aïn Sbylia” Arabic translation of “source of Seville”. It is around this source that the Mellah, the Jewish quarter, was built.

Debdou can boast a long tradition of hospitality. Thus, it has welcomed the Jewish populations expelled from Spain and which came to add to those already settled in the city. The Jews felt safe there. The city is protected by the mountains, the Anti-Atlas plateau, and steep terrain that made it safe from attack. As it was located off-center, it was less exposed than cities such as Fez or Marrakech, which regularly experienced unrest related to the conquest of power.

What is special about the Jews of Debdou? First of all, the fact that they were for a long time in the majority in this town, making up in fact three-quarters of the population. At the beginning of the 20th century, Debdou was proportionally the town with the largest population in Morocco.

In the Jewish world, Debdou was known above all for the making of law scrolls by the sofer סופֵר(scribes), who were true experts appreciated for their piety and their exceptional knowledge. The calligraphy of Debdou was known beyond Morocco. In Israel, one can appreciate today a very rare Sefer-Torah from Debdou, written on a deer skin parchment. It was a gift to former Prime Minister Yitzhac Rabin. (52)

The history of this city, now forgotten, is edifying and extraordinary. Over time, it became a hotbed of enlightened Judaism, a mecca for Talmudic studies whose reputation and influence extended from Morocco to neighboring Algeria. For Jews exiled from the Iberian Peninsula and nostalgic for the glory days before the Christian persecutions, life in Debdou was an extension of the Seville era. This period was the golden age of Debdou. (53)

In the 15th century, Debdou was a fortified and powerful citadel. This is the period of the Kings of Debdou. Debdou is no longer a city, it is a kingdom that weighed of all its weight on the Moroccan dynastic destiny. This kingdom was so powerful that the Alaouite dynasty had to turn to Ibn Mashcal, the Jewish ruler of Debdou and Taza, to find human and financial support. Without this support, the first Alaouite sultan would probably not have been able to establish his power. Indeed, it is thanks to the powerful support of Ibn Machcal that the first Alaouite sovereign was able to negotiate with the Rhiata, the Branes, Tsoul, Gzennaya, Mtalsa, and Aït Wrayn a bayca which was granted to him. The majority of Moroccans forget that the first capital of the Alaouites was none other than Taza from where the conquest of Fez was undertaken.

The Jewish Kingdom of Debdou

The Jewish history of this place is edifying on the weight of Judaism in the Moroccan dynastic destiny. Indeed, Debdou was the center of a historically known Jewish kingdom. There was only one mosque in the area and a dozen synagogues. This Jewish kingdom was so powerful that the Alaouite dynasty had to turn to Ibn Mashcal, the Jewish ruler of Debdou and Taza, for human and financial support. Without this support, the first Alaouite sultan would probably not have been able to establish his power. Indeed, it is thanks to the powerful support of Ibn Mashcal that the first Alaouite sovereign was able to negotiate with the Rhiata, the Branes, Tsoul, Gzennaya, Mtalsa and Aït Wrayn a baïâa which was granted to him.

The first capital of the Alaouites was none other than Taza from where the conquest of Fez was precisely engaged. In reality, the history of Debdou is that of a city located on the caravan trade route linking the Sahelo-Sudanese region via the Touat-Tafilelt to the Mediterranean. This trade was to run out of steam when the Europeans managed to divert it via the sea route. The Jewish community of Debdou has experienced various vicissitudes that have hit it hard. One of these vicissitudes in the history of Debdou was the defeat inflicted on the army of Sultan Moulay Abderrahmane (1778-1859) during the battle of Isly (1844).

The Jews of Dedbou left the city and withdrew to the tribal Kasbahs reserved for the Jews among the Rhiata, the Branes, and the Gzennaya. Many of them had converted to Islam. Even though cholera almost decimated the community in the 18th century, at the end of the 19th century, two-thirds of the population of Debdou were Jews. Today, what remains of this community has migrated entirely to Israel. Thus, Morocco was the first Jewish state in the world (after the exile) and this long before the appearance of Israel. (55)

Debdou was a Jewish city par excellence, inhabited by Jews who came from Spain at the time of the Arab conquest of that country. “Debdou la Juive” as it was called in the 16th century, occupied a great place in the Jewish intellectual movement of the 15th and 16th centuries. Several rabbis, through their religious as well as secular science, illustrated this period which was a glorious moment in the history of Moroccan Judaism.

Their disciples were the greatest Rabbis and Debdou is proud to have been able to maintain this intense religious center despite the numerous persecutions of the Arabs. To this day, this small town has had the honor of having given birth to a good number of rabbis spread throughout North Africa, the most revered of whom, and the worthiest of general admiration, are Rabbi Chelomo Cohen, President of the Rabbinical Tribunal of Mazagan, and Rabbi Bensoussan Aziz, President of the Rabbinical Tribunal of Mogador.

Aaron ibn Mashcal

Aaron ibn Mashcal was a Jewish ruler who ruled the kingdom of Debdou, in eastern Morocco, in the 17th century. His figure is a mixture of legend and historical reality. He was a character of primary importance for the rise to power of the Alaouite dynasty, which still reigns in Morocco. (56)

After the death of the famous Sultan of the Saadi dynasty (1549-1659), Ahmad al-Mansur (1549,1603), Morocco entered a period of turbulence marked by civil war for the throne between the sons of the late sultan, and the fragmentation of the country to the benefit of different warlords. (57)

At the beginning of the reign of Zaydan al-Nasir who ruled from 1603 to 1627,the Sultanate was weakened. The mystical brotherhood of Zawiya Dila controlled the center of Morocco, while the Zawiya of Illigh extended its influence over the regions of Sous and Draa and the warlord Sidi al-Ayashi took possession of the plains, the coasts of the northwest Atlantic, Salé became a republic ruled by privateers, Tetouan became a city-state ruled by the family Naqsis. [3] In the region of Tafilalet the Alaouites founded an independent principality. (58)

Among the many lordships were formed, there was also born a Jewish kingdom: The Kingdom of Debdou, which included the region Taza, Debdou was the capital, there were dozens of synagogues opposite a mosque.

The city’s Jews descended mainly from Jews of Seville They sought refuge in the city after anti-Jewish riots broke out in the Kingdom of Castile in 1391. The city was rich thanks to its strategic position made the center of trade between the Sahel, Tafilalet, and Mediterranean. The last (and perhaps the first) ruler of this kingdom was Aaron ibn Mashcal.

According to legend, he became so powerful and feared that, as a tribute to keep the peace, asserted each year by the city of fez a young Muslim virgin. the Alaouite Sultan ar-Rashid was attracted by the legends about the immense wealth and military and political influence of Ibn Mashcal, and initially sought an alliance with this Jewish king. Without the support of Ibn Mashcal, probably ar-Rashid could have never consolidated his power. It was thanks to Ibn Mashcal that the sultan was able to negotiate and receive recognition from the tribes of Rhiata, Branes, Tsoul, Gzennaya, Mtalsa and Ait Wrayn.

Increasingly eager for the wealth Ibn Mashcal, Moulay ar-Rashid sent a student, disguised as a beautiful virgin, who managed to enter the residence of the Jewish ruler, killing him, and allowing the sultan to take possession of his wealth and his kingdom, and establishing his capital temporarily in Taza and forming a large army, preparing for the conquest ofSijilmasa and fez.

Nevertheless, there was throughout history a great intimacy between the Jews and the Alaouite dynasty as stated clearly by Robert Assaraf: (59)

[‘’The history of the Alawite dynasty begins in 1666 with the reign of Moulay Rachid. If we exclude the case of a particularly tyrannical and openly anti-Semitic sultan, Moulay Yazid, the Alawites have cultivated throughout the centuries – and still do – a great intimacy, if not complicity, with Moroccan Jews, because of their responsibilities as religious leaders and in their capacity as Amir El Mouminin (Commanders of the believers). While it is true that there were many abuses, they were rarely committed by the sultans, but rather by local authorities, dissident tribes, or the rebellious populace, usually in times of political or dynastic uncertainty.

The persecutions from which the Jews suffered were not the result of any fatality but of the weaknesses of the central power. Jews and Muslims shared their share of misery and humiliation. But because they constituted a vulnerable religious minority, the Jews were more willing to dramatize their fate. Thus, from the middle of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, they were relatively more permeable to European influences, in particular to the “civilizing” role of France.

A medieval country at the beginning of the dynasty, more often closed in on itself than open to ideas and techniques from the open sea, Alawite Morocco did not, however, have a body of anti-Semitic doctrine or a declared policy of discrimination. The massacres or exactions that punctuate a history of more than three centuries can be explained by general factors that go beyond the fate of the Jews alone…’’]

‘’L’histoire de la dynastie alaouite commence en 1666 avec le règne de Moulay Rachid. Si on exclut le cas d’un sultan particulièrement tyrannique et ouvertement antisémite, Moulay Yazid, les alaouites ont cultivé au long des siècles — et cultivent encore — une grande intimité, sinon une complicité, avec les juifs marocains, en raison de leurs responsabilités de chefs religieux et en leur qualité de Amir El Mouminin (Commandeurs des croyants). S’il est vrai que les exactions furent nombreuses, elles furent rarement commises par les sultans, mais plutôt par des autorités locales, par des tribus dissidentes ou par la populace en révolte, généralement en période d’incertitudes politiques ou dynastiques.

Les persécutions dont eurent à souffrir les juifs ne procèdent pas d’une quelconque fatalité mais bien des faiblesses du pouvoir central. Juifs et musulmans ont partagé leur lot de misère et d’humiliations. Mais, parce qu’ils constituaient une minorité religieuse Vulnérable, les juifs dramatisèrent plus volontiers leur destin. Ils seront ainsi, dès le milieu du XIXe siècle et au début du XXe, relativement plus perméables aux influences européennes, en particulier au rôle « civilisateur » de la France.

Pays médiéval aux débuts de la dynastie, plus souvent recroquevillé sur lui-même qu’ouvert aux idées et techniques venues du grand large, le Maroc alaouite n’a pourtant connu ni corps de doctrine antisémite ni politique déclarée de discrimination. Les massacres ou exactions qui jalonnent une histoire vieille de plus de trois siècles s’expliquent par des facteurs généraux qui dépassent le sort des seuls juifs…’’

the Tolba (Students of Quranic schools) in Fez remember and still celebrate the anniversary of the assassination of Ibn Mishcal, which had thrown the city of Fez into panic, the city had to pay tribute to him.

The festival of the Sultan of the Tolba (La Nozhat Talaba), or the Sultan of the Students, (60) has been described by many travelers since the 19th century. This festival took place in Fez (or Marrakech) every year in spring. The office of the Sultan of Carnival was sold at auction. This pseudo-sultan surrounded himself with a court and imitated the acts and behaviors of the royal court, as many high officials were imitated in a grotesque way. The real sultan agreed to satisfy the demands of his double (in reality the person who had financed the purchase of the office by the penniless student). After a week, everything was back to normal and the fake sultan disappeared. Obviously, it is the question of power that is raised by this ritual. But just as much it is the question of knowing if this ritual really enters the category of theater or if it is not only a form of theatralization. It is absurd to believe that there could have been theater in ancient Moroccan society.

Popular legends trace this student tradition to the early reign of Moulay ar-Rashid the Alaouite (1644-1672). Around 1664, Moulay ar-Rashid is said to have authorized the Tolba of al-Qarawiyine university to elect a sultan from among themselves each year, as a reward for their help in eliminating a Jew named Ibn Mashcal, who ruled despotically over the cities of Taza and Fez. After the death of Moulay ar-Rashid in 1671, his brother and successor Moulay Ismael preserved this tradition which was respected and perpetuated by the Alaouite rulers for centuries and until a very recent date.

On the account of this celebration of the Tolba of Fez, which is still perpetuated today, Weill writes: (61)

[‘’The Tolba, or medersa students, celebrate a burlesque festival every year in the second half of April, which includes the appointment of a Sultan, a sort of “carnival king” whose crown is auctioned off, who presides over all sorts of festivities, receives gifts, and for a few days enjoys extensive powers, including that of jokingly haranguing and parodying the real Sultan and his court. If the Makhzen tolerated these irreverent facetiousnesses, it was, according to the Fasis, to reward the Tolba for having given the throne to the first sovereign of the Filalian dynasty in the XVth century. During the anarchy that marked the last years of the Sa’dian reign, a Jew by the name of Ibn Mechal seized power, according to the legend. King of Taza, he terrorized the region and demanded that the people of Fez deliver to him the most beautiful young girl of the city for his harem. Moulay-er-Rachîd, a student in Fez, implored by the mother of the designated victim, young, handsome and beardless, veiling himself with a haïk, pretended to be the young girl, and went to Taza with great pomp, accompanied by forty chests containing ornaments. Ibn Mechal made the procession enter his palace. From the chests came out forty tolba, who massacred the tyrant. Er-Rachîd, proclaimed sultan, returned in triumph to Fez and married the young girl. Such is the legend. The Arab sources, the oldest of which is 60 years after the accession of Er-Rachid, which took place in 1664, and the European sources, English and French, which are almost contemporary with the events, relate the facts in a much more sober manner, but fantasy still has its share. M. de Cenival believes he can, by confronting the various documents relating to Moulay-er-Rachîd and by classifying them, identify the primitive history, which is very simple, and follow the later developments of the legend which was grafted onto it.’’]

‘’Les Tolba, ou étudiants des médersas, célèbrent chaque année, dans la seconde moitié d’avril, une fête burlesque comportant la nomina¬ tion d’un Sultan, sorte de «roi de carnaval », dont la couronne est mise aux enchères, qui préside à toutes sortes de réjouissances, reçoit des cadeaux, jouit quelques jours de pouvoirs étendus, jusqu’à celui de haranguer plaisamment et de parodier le vrai Sultan et sa cour. Si le Makhzen tolère ces facéties irrévérencieuses, c’est, au dire des Fasis, pour récompenser les Tolba d’avoir autrefois donné le trône au premier souverain de la dynastie filalienne, au xvne siècle. A la faveur de l’anarchie qui marqua les dernières années du règne des Sa’diens, un juif du nom d’Ibn Mechal se serait, à en croire la légende, emparé du pouvoir. Roi de Taza, il aurait terrorisé la région et exigé des gens de Fès de lui livrer pour son harem la plus belle jeune fille de la ville. Moulay-er-Rachîd, étudiant à Fès, imploré par la mère de la victime désignée, jeune, beau et imberbe, se voilant d’un haïk, se fit passer pour la jeune fille, et se rendit en grande pompe à Taza, accompagné de quarante coffres enfermant des parures. Ibn Mechal fit entrer le cortège dans son palais. Des coffres sortirent quarante tolba, qui massacrèrent le tyran. Er-Rachîd, pro¬ clamé sultan, rentra en triomphe à Fès et épousa la jeune fille. Telle est la légende. Les sources arabes, dont la plus ancienne est posté¬ rieure de 60 ans à l’avènement d’Er-Rachîd, qui eut lieu en 1664, les sources européennes, anglaises et française, presque contemporaines des événements, relatent les faits de façon beaucoup plus sobre, mais la fantaisie y a encore sa part. M. de Cenival croit pouvoir, en confrontant les divers documents relatifs à Moulay-er-Rachîd et en les classant, dégager l’histoire primitive, fort simple, et suivre les développements ultérieurs de la légende qui s’est greffée sur elle.’’

Life in Debdou

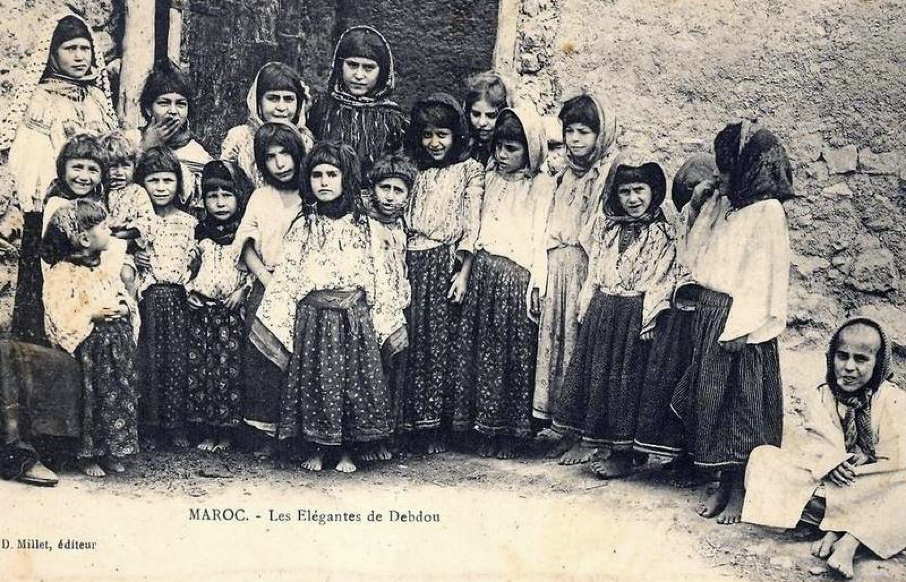

In his description of Jewish life in Debdou, Darmon Abner, (62) a French soldier turned teacher, in his description of the Mellah and the dwellings insists on the destitution – the “worm-eaten” doors -, the absence of hygiene – “the narrow streets of the Mellah where unfortunately no principle of hygiene is still observed” (p. 6), the promiscuity with animals in the courtyard of the houses, the absence of ventilation in the rooms of the houses which often have only one opening, and the fact that the families sleep together, even in the summer, in a single room “in a promiscuity that is in stark contrast to their austere morality’’. (63)

But it is especially in the paragraphs devoted to the Jewish women of Debdou and the rites of marriage that the author lets his ‘’indignation’’ explode pushed mainly by his feeling of pseudo-superiority:

[“The Jewish women of Debdou are unfortunately the innocent victims of a deplorable practice: early marriages are frequent there and a young girl who has reached the age of 16 has long been discarded. It is not uncommon, despite the platonic character of which the early unions claim to be, to meet girls of 13 to 14 years withered prematurely.”]

‘’Les Juives de Debdou sont malheureusement les victimes innocentes d’une pratique déplorable : les mariages précoces y sont fréquents et une jeune fille qui a atteint 16 ans est depuis longtemps mise au rebut. Il n’est pas rare, malgré le caractère platonique dont se réclament les unions hâtives, de rencontrer des fillettes de 13 à 14 ans flétries prématurément.’’ (P. 10.)

The fact that most marriages are consanguineous is noted without further comment, but this detail appears, in the economy of the text, as an additional sign of the enclosure of the community. Endogamy is also reflected in the particular “type” of women who “[have none of the physical characteristics of their co-religionists from Algeria or even Morocco]/’’n’ont aucun des caractères physiques de leurs coreligionnaires d’Algérie ou même du Maroc’’” (p. 10), but whose features, blue eyes and blond hair would rather evoke a “Spanish type”.

Darmon Abner in his booklet, poses as a condescending European who sees the world around him with a haughty air, not to say inquisitive and giving lessons to others even if they are his co-religionists. He rejects the thousand-year-old traditions and seems to condemn them without any restraint, or sheer knowledge of their humanity, as practices of backward people.

His descriptions of the wedding rites quickly move away from the folkloric description of the family and neighborhood festivities to evoke rather the pitiful fate of the young girl, or more exactly of the girl child. The ritual bath is described as a ‘’torture session’’ in winter when the water is frozen:

[“The thin layer of ice is broken and, in spite of the cries of pain that the unfortunate woman utters, a vigorous hand supports her by the hair and plunges her two or three times into the purifying bath. This is the beginning of a painful ordeal for her because the impatient husband – now that the priest18 has consecrated the union – does not always wait, in spite of his promises, until his young spouse has reached the age of puberty to assert his rights.”]

« La mince couche de glace est brisée et, malgré les cris de douleur que pousse l’infortunée, une main vigoureuse la soutient par les cheveux et la replonge à deux ou trois reprises dans le bain épuratoire. C’est là pour elle le commencement d’un douloureux calvaire, car l’époux impatient – maintenant que le prêtre18 a consacré l’union – n’attend pas toujours, malgré ses promesses, que sa jeune conjointe ait atteint l’âge de la puberté pour faire valoir ses droits. » (P. 11.)

Abner’s attitude embodies the European liberator and bringer of the light of white civilization to the backward peoples living in the darkness of ignorance and this is the message contained in his conclusion:

“And to close our study, we must wish that the French influence expunges as soon as possible, from the local traditions of Debdou, what they may still have of deplorable. Let us also hope that it does not damage, in this small people, its own originality, the distinctive character of its civilization.’’

‘’Et pour clore notre étude, nous devons souhaiter que l’influence française expurge au plus tôt, des traditions locales de Debdou, ce qu’elles peuvent avoir encore de déplorable. Souhaitons aussi qu’elle n’entame point, chez ce petit peuple, son originalité propre, le caractère distinctif de sa civilisation.’’

Thus for him the European culture is not only the only alternative that this world waited for more than 2000 years but it is also saving from backwardness and ignorance.

Conclusion

A whole world vanished, as it were, during the last century. Moroccan Judaism has undergone French or Spanish influence, even though it was the vehicle for a particularly rich Judeo-Arabic, Judeo-Spanish, and Judeo-Berber cultures. The great social upheavals that accompanied the transition to modernism and the various migrations that the community has experienced have meant that the ancestral cultural heritage has been somewhat neglected. It is well known that present generations of Moroccans, Muslims and Jews, are looking more and more into its past and trying to reconstitute the elements that allowed it to survive and flourish in a context that was not always the most favorable. (65)

For the Moroccan historian Mohammed Kenbib, the Judeo-Muslim coexistence in Morocco is a sound reality though it was punctuated by dire times and numerous hardships:

[‘’The centuries-old cohabitation between the Jews and their neighbors, based on cultural, social and economic foundations, consolidated over time and through the course of time and the ordeals experienced in common, was from time to time going through difficult phases, punctuated by all kinds of turbulence and violence. It was, in particular, the case, during the rebellions of tribes and of their “descents” on the cities, of disorders in the big cities, of inter-regnum troubles, natural calamities such as the persistence of drought, foreign drought, foreign invasion and millenarian tensions.’’]

‘’La cohabitation multiséculaire entre les Juifs et leurs voisins, basée sur toutes sortes de fondements culturels, sociaux et économiques consolidés au fil du temps et les épreuves vécues en commun, traversait de temps à autre, à l’évidence, des phases difficiles, ponctuées de toutes sortes de turbulences et de violences. C’était notamment le cas lors des rebellions de tribus et de leurs “descentes” sur les villes, de désordres ans les grandes cités, de troubles d’inter-règnes, de calamités naturelles telles que la persistance de la sécheresse, d’invasion étrangère et de tensions millénaristes.’’

“Allah ybarek f cmar sidi” in the mouth of Israeli special national security advisor Meir Ben Shabbat, the time-honored phrase came as a surprise. (66) The expression is ritually pronounced by Moroccan notables during the Feast of the Throne, and testifies to their renewed loyalty to the king. The Israeli Prime Minister’s advisor, Benyamin Netanyahu, made a symbolic pledge of allegiance when he was received by King Mohammed VI at the Royal Palace in Rabat on the occasion of the agreements signed between Morocco and Israel on December 23, 2020. And who recalled how the Jewish community of Moroccan origin retains strong ties with the Sherifian monarchy.

The majority of Moroccan Jews left to Israel after the Six-Day War in 1967 but for Shlomo Miara, Rabbi and Moroccan writer of Jewish origin, though they have their feet in Israel they still have their hearts in Morocco. Indeed, Moroccan Jews have lived in Morocco among Muslims for more than 2500 years. They found refuge there after their multiple expulsions from Asia (Mesopotamia 560 BC and Palestine 71 AD) and Europe (Spain and Portugal 1391 and 1492). The Moroccan people and their sultans welcomed them with open arms.

Certainly, their long history in Morocco was not without some pogroms and persecutions, but generally speaking their place in the hearts of Moroccans was always great to the point that they were always yesterday and today great intercessors of the country in diplomacy, politics, finance, and business. Throughout history, they shared with Moroccan Muslims beliefs, (67) festivities (68) and culture (69) without any ambiguity but rather with great conviviality. Moroccan Muslims still carry them in their hearts: they regret their departure and are the guardians of their cemeteries and shrines of their saints as well as their schools, synagogues and Mellahs. Today, what remains of this community has emigrated entirely to Israel. A destiny both Homerian and Cornelian!

Annex I: Jewish extended families of Debdou

1-Ben Hammou, Haron di Chmouel, Ben Soussou Sbiaâ, Avida Asmimen, Zaroual Touita, Salem, Massôd, Ben Zagai, Sbata, Fofo, Lekdim, Soussous Amouchi, Dabid, Ben Waw, Bar Rafaël, H’kika, Tababa, Bziza’h, and Bouz’ît.

The leader of the local resistance during the Hilalian invasions in the region in the 15th century was called Moussa Ben Hammou.

2- Benaïm.

3- Aconina, Ben Conina, Tsiguiour, and Chouaâ.

4- Benguigui, Âtsidi, Sbiaâ, Asmimen, and Touita (this tribe came from the Sahara Desert around the 17th century).

5- Bensultan,Benissim, Bentata, Benefraim, andBenchmouel (this tribe is of Spanish origin. It presence in Debdou dates back to the 17th century).

6- Marelli, Ben Harona, Oulad Mniguets, Zemama (these tribes came from Morella (Spain) after the Reconquista).

7- Tordjman (Does it go back to the 18th19th century? There are different hypotheses as to its origin: either it is an offshoot of the Bensoussan or the Marciano or it would be due to the installation of a Tordjman in Debdou during the 19th century).

8- Bensaoud.

9- Cohen Saqali (the Cohen Saqali have an Aaronic origin from the lineage of Zadok. They originate from the city of Seville), Cohen Sabban Archidi, Benaoud Benisrael, D’cheikh, Aryaich Lougzal, Benchmouel Boukaâva, Zagouri Leknouch, Daresther Tsfia’h, Lebagdadi, Naâs Benoughraba, Lebitiwi, Hamiza, Akouch Lefsoukh, Benbouzi Elbouz, Benmchich Enbouz, Bennafha, Benzamila, Ben’hida, M’Khelef, D’Icohen, Mhigan, Benchmiân, Barmalil, D’Imagrod, L’mokhalt, Aouz Eregba, Bousseta, Tmiss, L’aâjya, Roubin, and Tamar.

10- Bensoussan (of Sephardic origin, present in Debdou since the 16th century), Coulilef, Bentana, Bziz, Mrika, Douieb, Soussan, Boussabaniya, Benbéridi, Ben Chimon, Brihem, Benâlou, and Manina.

11- Marciano, Belchguer, Ben Ako, Ako, L’herher, Limama, L’khihel, Ben Aouizer, Ben Bibi, Mchicho-L’himmer, Bihi, Alouga, Ben Ychou, and Ben Yaza’h.

Cross-referenced sources:

M. Nehlil, M. ‘’Notice sur les tribus de la région de Debdou’’, Bulletin de la société de géographie d‘Alger et de l’Afrique du Nord, quatorzième année, tome XVI, 1911.

Slouchz, Nahum. ” Les Juifs de Debdou”, Revue du monde musulamn, Paris, 1913, pp. 221 -269.

Martsiʼano, Eliyahu Refaʼel, et al. Une nouvelle Séville en Afrique du Nord: histoire et généalogie des Juifs de Debdou (Maroc). Paris : Éditions Élysée, 2000.

Annex II: A Road That Leads Nowhere Else

‘’Debdou is at the end of a road which leads nowhere else. It is a small town which today is left apart, unaffected by the many highways and railroads that connect the rest of eastern Morocco to Oujda and Algeria. The plateau and steppe rise suddenly to form rolling hills that reach over 1650 meters.

Beyond the hills is a relatively green zone 25pecific a to horticulture, which stretches 40 kilometers to Moulouya. There lies Debdou, which in 1973 was still home to seven Jewish families, the last members of a once thriving community, which especially at the turn of the century, made up the majority of the town’s inhabitants. Today, it is a small market town and a meeting place for pastoral tribes and hunters who go there for the abundant fowl and game found nearby.

It is hard to imagine that Debdou was ever any different. But if you scour the map with the eyes of an ancient caravan 25pecific , it is easy to understand its advantageous position as a secure and resourceful junction between Taza, Fes, and Tlemcen. The trail descends the Atlas through the Moulouya valley to join the route which comes up from Tafilalt, linking the Sahara to the Mediterranean and Algeria.

This explains Debdou’s commercial and political importance in the eyes of the Makhzen and regional powers. This position also explains how Debdou became a center of learning and culture for the Jewish community. Heavily influenced by Fez, Tafilalt, and Tlemcen, it became home to the first “Sevillian” refugees from Spain in 1391.

This first wave of Spanish refugees had only a small impact on Moroccan Judaism, but the communities of Tunis, Algiers, and Tlemcen can trace some of their ancestry back to the exodus from the Kingdom of Aragon, which sparked the fi rst great crisis of Spanish Judaism. It is hard to trace the path followed by the Megorashim who ended up in Debdou. Did they go there “directly” or rather slowly, after an extended stay in Oran? Either way, there is an obvious similarity between the Jewish dialects of Debdou, Tlemcen, and Algiers.

The Jews of Debdou, or more 26pecific ally their two dominant clans, the Kohen Skalli and Ulad Marsiano (or Morsiano) were strongly attached to their roots in Seville, and until 1929, they still used the name Sbilia (Seville) on all starots (contracts). They even went as far as to symbolically name the main water well in town Aï n Sbilia. In fact, before arriving in Debdou, the Ulad Marsiano had settled in Kasbah el Makhzen, leading to believe that the settlement of the region by Geros Sebiyanos took time and happened in several stages. They assimilated with the local population in Debdou and were joined by other Baldiyyin families.

A massive migration then took place in the 17th Century, taking the Jews from Debdou to Dar Mashaal, in the Beni-Snassen foothills. They returned in 1690 when Moulay Ismaï l destroyed their village. This community, which was very active in both local and long-distance trade, spread quickly throughout the Oriental region of Morocco: Ksabi, Missur, Utat al-Hazz, Taza, Oujda, Taourirt, Guersif, Midelt, the Rif and Melilla; Algeria too. Finally, close ties with Tlemcen and Algeria had an infl uence on the Debdou dialect, and there are common loanwords from Spanish in the dialects of Oran, Oujda, and Debdou. French infl uences mostly came from Algeria… ‘’

Simon Lévy (1934-2011), Founder of the Museum of Moroccan Judaism in Casablanca.

Excerpt from: Région de l’Oriental. The Jewish Heritage of Eastern Morocco. Casablanca : La Croisée Des Chemins, 2021. https ://www.oriental.ma/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/The-Jewish-Heritage-of-Eastern-Morocco.pdf

Endnotes:

- Lecomte, Michel, contrôleur civil adjoint. Étude des tribus de l’annexe de Debdou. Mémoire présenté pour l’admission des hautes études administratives marocaine, février 1953.

- Nehlil, M. ‘’Notice sur les tribus de la région de Debdou’’, Bulletin de la société de géographie d‘Alger et de l’Afrique du Nord, quatorzième année, tome XVI, 1911.

- Le Glay, Maurice. La Mort du Rogui. Paris : Berger-Levrault, 1926. https://books.google.be/books?id=ajw0AAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=fr&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Slouchz, Nahum. ” Les Juifs de Debdou”, Revue du monde musulamn, Paris, 1913, pp. 221 -269.

- Cour, A. ‘’Debdu’’, Encyclopédie de l’Islam (Première édition), I, pp. 958-960.

- Pellat, Ch. ‘’Nemrod et Abraham dans les parlers arabes des Juifs de Debdou’’, Hespéris, t. XXXIX, 1953, pp. 1-15.

- Foucauld, Ch. Reconnaissance au Maroc. Paris : Challamel, 1888, t. 1, pp. 248-250.

- Slouchz, Nahum. ” Les Juifs de Debdou”, Revue du monde musulamn, op. cit.

- El Briga, C. “Debdou”, Encyclopédie berbère, 15, document D27, 1995, pp. 2254-2255. http://journals.openedition.org/encyclopedieberbere/2230

- Gampel, Benjamin R. Anti-Jewish Riots in the Crown of Aragon and the Royal Response, 1391–1392. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Darmon, Abner. “Petite étude sur les Juifs de Debdou (Maroc) à l’époque de la Première Guerre mondiale”, in Bocquet, Jérôme (ed.). L’enseignement français en Méditerranée : Les missionnaires et l’Alliance israélite universelle. Rennes : Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2010, pp. 301-309. http://books.openedition.org/pur/103295

- Slousch, Nahum. ‘’Etude sur l’histoire des juifs et du judaïsme au Maroc’’. Publication de la Mission Scientifique du Maroc, in Archives Marocaines, vol. 40, 1905, pp. 345-411.

- Martsiʼano, Eliyahu Refaʼel, et al. Une nouvelle Séville en Afrique du Nord: histoire et généalogie des Juifs de Debdou (Maroc). Paris : Éditions Élysée, 2000.

- Meakin, Budgett. The land of the Moors; a comprehensive description. London: S. Sonnenschein & co. lit.; New York: The Macmillan company, 1901. https://archive.org/details/landofmoorscompr00meak/page/n11/mode/2up

- Kaukonen, Emil. ‘’ Science in the Time of the Plague: Jakob Gråberg and the Moroccan Plague Epidemic of 1818–20’’, Arcadia, Autumn 2020, no. 38. https://www.environmentandsociety.org/arcadia/science-time-plague-jakob-graberg-and-moroccan-plague-epidemic-1818-20

- Bulletin de l’Alliance israélite universelle, January 1, 1897, p. 69 and January 3, 1904, p. 98.

- British National Archive-Confidential, Department series, Near East and North Africa Department DS No 3/75. The Jewish Community in Morocco, From Her Majesty’s Ambassador at Rabat to the Secretary of state for foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, Rabat 18 March 1975.

- Slousch, N. ‘’Les Juifs de Debdou’’, Revue du Monde musulman, vol. XXII, Paris, Ernest Leroux, 1913 (http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k103817g)., op. cit., p. 238.

- Ibid., p. 267.

- Boum, Aomar & Park Thomas K. Historical Dictionary of Morocco. Third Edition. London, New York: Rowan & Littlefield, 2016.

- Maalouf, Amin. Leo the African. London: Time Warner Books Uk, 1994.

- Nahum Slousch’s insistence on evoking the glorious episodes of Debdou’s history, from the viceroyalty of the fifteenth century to the Jewish kingdom of Ben Mechaal, the claim of autonomy vis-à-vis the Muslim authorities that he lends to the Jews of Debdou, and the links with Palestine that he mentions are consistent with the author’s Zionist commitment. This commitment earned him the resolute opposition of Lyautey and Gouraud to his appointment as advisor to the Moroccan state for Jewish affairs, and to the establishment of a chair of Jewish language and civilization.

- Shorfâ pl. Shrîf: descendant of the Prophet Muhammad.

- Kenbib, Mohammed. ‘’Études et recherches sur les Juifs du Maroc: Observations et réflexions générales’’, Hespéris-Tamuda LI (2), 2016, pp. 21-55. https://www.hesperis-tamuda.com/Downloads/2010-2019/2016/fascicule-2/2.pdf

- ‘’Taourirt: Debdou, berceau confessionnel, renaît de ses cendres’’, L’Économiste, 10 mars 2014. https://www.leconomiste.com/article/920591-taourirt-debdou-berceau-confessionnel-rena-t-de-ses-cendres

- Belachemi, Jean-Louis. Nous, les frères Barberousse, corsaires et rois d’Alger. Paris : Fayard, 1984.

- Chouraqui, André. Between East and West: A History of the Jews of North Africa. New York: Scribner, 1973

- Slousch, Nahum. ‘’Résultats historiques et épigraphiques d’un voyage dans le Maroc oriental et le Grand Atlas’’, Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 58-2, 1914, pp. 179-185. https://www.persee.fr/doc/crai_0065-0536_1914_num_58_2_73366

- Lecomte, Michel. ‘’Il était une fois Debdou’’, https://debdou.fr/il-etait-une-fois-debdou/

- It is through the south of the Taza corridor that the “Marinids’ road” used to pass: the famous “Trîq Sultân” that linked Fez to Eastern Morocco via Sefrou, Rchida and Debdou. The transhumant Bni Waraïn and Houwara Oulad Rahou arrived at the corridor of Taza in the wake of the Marinids from Figuig where they nomadized formerly.

- Darmon, Abner. “Petite étude sur les Juifs de Debdou (Maroc) à l’époque de la Première Guerre mondiale”, op. cit.

- Une nouvelle Séville en Afrique du Nord, op. cit., p. 6, p. 83 and p. 89-91.

- https://moreshet-morocco.com/category/debdou-histoire/

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Martsiʼano, Eliyahu Refaʼel, et al. Une nouvelle Séville en Afrique du Nord: histoire et généalogie des Juifs de Debdou (Maroc), op. cit.

- Don Isaac Abravanel was one of the greatest Jewish statesmen who played an important part in European history. At the same time he was not merely a loyal and strictly religious Jew, but a great scholar, Bible commentator and philosopher. He was the last of the long line of great Jewish leaders and heroes of the Spanish Golden Age.

- Nacik, Lhaj Mohamed. ‘’ The Emigration of Moroccan Jews to Palestine After the Six-Day War A Report by Mr. P. M. Johnston the British Consul, Casablanca (February 1968)’’, Hespéris-Tamuda, LIII (3), 2018, pp. 165-196. https://www.hesperis-tamuda.com/Downloads/2010-2019/2018/fascicule-3/7.pdf