Sudan And South Sudan Energy Profile – Analysis

By EIA

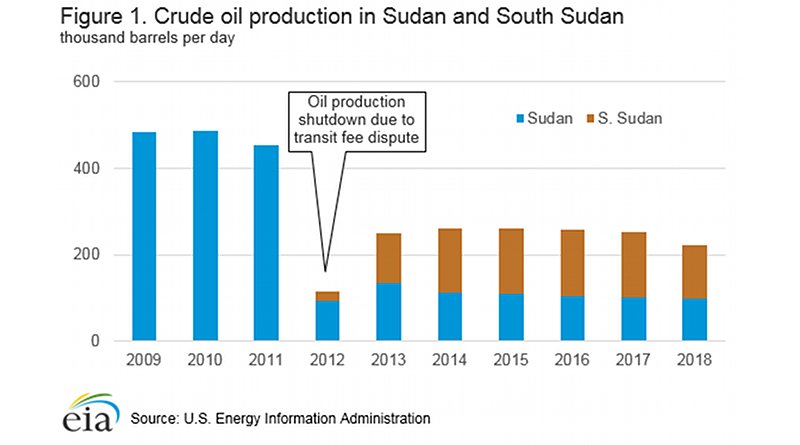

South Sudan was officially recognized as an independent nation state in July 2011 following a referendum held in January 2011. The South Sudanese voted overwhelmingly in favor of secession, which led to Sudan losing 75% of its oil reserves to South Sudan. Although South Sudan now controls a substantial number of the oil–producing fields, it is dependent on Sudan for transporting oil through its pipelines for processing and export. The transit and processing fees South Sudan must pay to Sudan to transport its crude oil are an important revenue stream for Sudan.[1]

After an agreement was reached on the transit dispute that led to a temporary shutdown of crude oil production, the governments of Sudan and South Sudan shifted their focus from border conflicts to the mitigation of their respective domestic opposition factions. The domestic political dynamics and the security situations in both countries will continue to be a potential risk for disrupting the countries’ oil supplies and exports.

In Sudan, the economic shock of the secession has had a significant effect on the economy, which has been hurt by economic mismanagement, corruption, and unsustainably high levels of spending on the military. The partial lifting of U.S. sanctions on Sudan in October 2017 has allowed for increased foreign investment, but Sudan has made little progress toward developing the upstream sector.[2] In August 2019, Sudan’s military and civilian leaders signed a power-sharing deal that paved the way for a transitional government led by Abdalla Hamdok, an economist, to take power in the hope this government would address the country’s problems. However, Sudan remains on the U.S. government’s list of state sponsors of terrorism, which prevents the country from receiving debt relief through the World Bank-International Monetary Fund’s Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative (HIPC).[3]

In South Sudan, President Salva Kiir and the leader of the main opposition faction, Riek Machar, reached a peace agreement in September 2018, which led to reduced violence from the civil war in South Sudan. Although the peace agreement indicates progress, whether the agreement will bring prolonged stability and an inclusive and stable form of governance is unclear. The current agreement is similar to the previous one, which was signed in 2016 and collapsed after two months, and the current iteration does not address crucial elements such as power sharing between the factions and security arrangements that would allow Machar to safely return from exile.[4] Without significant progress in improving the security and political environment, South Sudan’s ability to attract investors and restart production at its fields to increase production will be limited.

Sector organization

Asian national oil companies (NOCs) dominate the oil sectors in both countries. The China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), India’s Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC), and Malaysia’s Petronas hold large stakes in the leading consortia operating in both countries: the Greater Nile Petroleum Operating Company, the Dar Petroleum Operating Company, and the Sudd Petroleum Operating Company.

The state–owned Sudanese Petroleum Corporation (SPC) was dissolved in March 2019, by order of Prime Minister Mohamed Tahir Ayala, and all assets and employees were transferred to the Ministry of Petroleum. The SPC was responsible for the exploration, production, and distribution of crude oil and petroleum products. The reason for the dissolution of the SPC has not yet been released.[5]

| Consortium/subsidiary | Company | Country of origin | Share % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greater Nile Petroleum Operating Company (GNPOC) | CNPC | China | 40 |

| Petronas | Malaysia | 30 | |

| ONGC | India | 25 | |

| Sudapet | Sudan | 5 | |

| Greater Pioneer Operating Company (GPOC) | CNPC | China | 40 |

| Petronas | Malaysia | 30 | |

| ONGC | India | 25 | |

| Nilepet | South Sudan | 5 | |

| Dar Petroleum Operating Company (DPOC) | CNPC | China | 41 |

| Petronas | Malaysia | 40 | |

| Nilepet | South Sudan | 8 | |

| Sinopec | China | 6 | |

| Tri-ocean Energy | Egypt | 5 | |

| Sudd Petroleum Operating Company (SPOC) | Petronas | Malaysis | 67.9 |

| ONGC | India | 24.1 | |

| Nilepet | South Sudan | 8.0 | |

| Petro Energy Operating Company (PEOC) | CNPC | China | 95 |

| Sudapet | Sudan | 5 | |

| Source: Company websites and presentations, Africa Oil & Power |

Petroleum and other liquids

Exploration and production

The lifting of U.S. sanctions imposed on Sudan has led to a renewed push by the Sudanese government to attract foreign investment in the upstream sector during the past few years, but Sudan has not made any substantial progress toward developing new fields that would lead to increased production.

In March 2019, an offer of 10 oil and natural gas exploration blocks in the Red Sea’s Halayeb triangle sparked a dispute between Egypt and Sudan. Egypt controls the territory, but Sudan has claimed the territory as Sudanese since the 1950s.[6]

South Sudan has restarted production at some of its previously shut-in fields in the Toma South and Unity fields in September 2018 and January 2019, providing a marginal increase to its total production. South Sudan seeks to increase total production to more than 200,000 b/d by the end of 2019. However, uncertainty remains on whether Sudan can do so under the export licensing restrictions the U.S. Department of State imposed on South Sudan’s Ministry of Energy, Nilepet (the National Oil and Gas Corporation of South Sudan), and the three major oil field operators in the country: DPOC, GPOC, and SPOC.[7] The licensing restrictions hinder the operators’ ability to secure the equipment and services required to develop or re-start production at its fields.[8]

In 2018, the government withdrew from negotiations to explore and develop blocks B1 and B2, and it is reportedly in talks with CNPC to acquire the blocks.[9]

Midstream infrastructure

Plans for the construction of a separate pipeline have been reported that would allow South Sudan to export crude oil through neighboring Kenya or Djibouti through Ethiopia to avoid transit fees.[10] However, the pipeline is not likely to be built in the near future because of the overall weak security environment and resulting supply disruptions to crude oil production in South Sudan.

Refining and refined oil products

Discussions between Sudanese and Chinese officials on a proposed second expansion to the refinery in Khartoum that could double the refinery’s capacity have been reported, but no significant progress has been made.[11]

Petronas signed a contract with the Ministry of Energy and Mining to expand the inactive Port Sudan refinery through a 50/50 joint venture and to add 100,000 b/d to its capacity, but development has been postponed as a result of rising costs.[12]

In South Sudan, two refineries were under construction: a 3,000-b/d refinery at Bentiu in the Unity State and a 10,000–b/d refinery at Thiangrial in the Upper Nile region. Plans to expand the Bentiu refinery to increase its capacity to 5,000 b/d have been reported. However, security issues have delayed completion, and unclear when or if the refineries will be operational is unclear.[13]

Petroleum and other liquids exports

According to ClipperData, Sudan and South Sudan exported about 114,000 b/d of crude oil in 2018. Although this level is higher than the 65,000 b/d exported in 2012 during the production shutdown, it is lower than the 182,000 b/d exported in 2014.

China is the largest export destination for Sudan’s and South Sudan’s crude oil. China received almost 60% of both countries’ total exports in 2018, although the total volume of exports has declined during the past few years. India and the United Arab Emirates have also imported relatively small volumes of Sudan and South Sudan’s crude oil.

Natural gas

Natural gas associated with oil fields is mostly flared or reinjected. Despite proved reserves of 3 trillion cubic feet, natural gas development has been limited. According to the latest estimates provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Sudan flared about 13.5 billion cubic feet of natural gas in 2017.[14]

Energy consumption

Petroleum consumption in Sudan and South Sudan peaked at 140,000 b/d in 2016 and has remained steady since then.[15]

In 2016, total primary energy consumption in Sudan was 0.357 quadrillion British thermal units (Btu) and in South Sudan was 0.017 quadrillion Btu, according to latest estimates. About 80% of total primary energy consumption in Sudan is derived from petroleum and other liquid fuels, and the remainder comes from renewables such as biomass. In South Sudan, nearly all of the primary energy consumption was from petroleum and other liquid fuels.[16]

Electricity

Sudan

Total electricity generation in Sudan was 14 billion kilowatthours (kWh) in 2016, of which 57% was generated by hydropower.[17]

Although power generation has continued to grow in the post-independence era, only 39% of the population had access to electricity in 2016, according to latest estimates from the World Bank.[18] Urban populations benefit from a substantially higher level of access than rural populations, according to the most recent estimates from the African Development Bank (AfDB). People who are not connected to a grid rely on biomass or diesel-fired generators for electricity.[19]

Given its heavy reliance on hydropower to meet its electricity needs, the government of Sudan has sought to diversify its power portfolio mix with thermal and even nuclear power sources. However, it is uncertain whether there will be significant progress towards constructing power plants utilizing these fuel types.[20]

South Sudan

Total electricity generation in South Sudan was 0.4 billion kWh in 2016, nearly all of which was generated by crude oil.[21]

South Sudan has one of the lowest electrification rates in the world; only 9% of its population had access to electricity in 2016, according to the latest estimates from the World Bank.[22]

In 2018, the government of South Sudan commissioned a 100 megawatt (MW) thermal power plant in Juba, which could potentially meet a substantial portion of the country’s electricity needs. The plant is expected to reduce consumption of heavy fuel, upon which generators, the primary source of electricity in the country, rely.[23]

The government of South Sudan signed an agreement with the government of Uganda in October 2017 to construct an interconnection line between the two countries. The line will connect the electricity grid in Kampala, the Ugandan capital, and supply electricity to Kaya and Nimule, two of South Sudan’s border towns. The agreement is reportedly in line with the East African Power Pool agreement and should address the serious lack of access to electricity in the remote and rural areas of South Sudan.[24]

Renewable Energy Sources

Hydroelectricity

Development of the Kajbar dam, located further north in the Nile Valley, has stalled. The dam was strongly opposed by local communities because of its potentially significant environmental impact, and there has been no sign of progress on its construction. The Kajbar dam, along with two other proposed hydropower projects, the Dal and El-Shireig dams, are heavily financed by the Saudi government.[25]

According to BMI Research, five hydropower projects have been identified as potential opportunities for development: Fula Rapids (42 MW), Grand Fula (890 MW), Shukkoli (230 MW), Lakki (410 MW), and Bedden (570 MW). However, construction has been delayed because of a lack of funding.[26]

Notes

- In response to stakeholder feedback, the U.S. Energy Information Administration has revised the format of the Country Analysis Briefs. As of December 2018, updated briefs are available in two complementary formats: the Country Analysis Executive Summary provides an overview of recent developments in a country’s energy sector and the Background Reference provides historical context. Archived versions will remain available in the original format.

- Data presented in the text are the most recent available as of September 5, 2019.

- Data are EIA estimates unless otherwise noted.

Endnotes

- IMF Country Report No. 17/73, March 1, 2017, pg. 6, accessed 1/10/2018.

- Sudan and Darfur Sanctions, U.S. Department of the Treasury Resource Center, accessed 10/17/2017. “US eases Sudan economic and trade sanctions,” Al-Jazeera, October 6, 2017, accessed 10/17/2017.

- “Improving Prospects for a Peaceful Transition in Sudan,” International Crisis Group, Briefing No. 143, January 14, 2019.

- “Bolstering South Sudan’s Peace Deal,” International Crisis Group, January 28, 2019.

- “Sudan dissolves state-owned Sudanese Petroleum Corporation,” Reuters News Agency, March 20, 2019.

- “Sudan says Egyptian Red Sea oil and gas blocks are on its territory,”Reuters News Agency, March 20, 2019.

- “South Sudan gears up to re–start shut–in oil fields with Sudan’s help,” IHS Markit, August 10, 2018.

- “US Imposes Oil Restrictions on South Sudan,” Middle East Economic Survey, Vol. 61, Issue 13, March 30, 2018.

- “Interview: South Sudan turns to China to develop key blocks after Total walks,”S&P Global Platts, September 10, 2018.

- “Regional Alliances Leave Juba in Two Minds Over Planned Oil Pipeline,” Middle East Economic Survey, Vol. 56, Issue 44, November 1, 2013, accessed 1/26/2018.

- “Sudan Plans 100kbd Hike,” Middle East Economic Survey, Vol. 58, Issue 44, October 30, 2015, accessed 10/25/2017. Also, “Company Overview,” Khartoum Refinery Company Limited, accessed 10/25/2017. “Black and white, China turns Sudan’s oil, cotton into gold,” XinhuaNet, August 25, 2017, accessed 10/25/2017. “Review of 15 Years of Sino–Sudanese Petroleum Cooperation,” China National Petroleum Corporation, accessed 10/25/2017. “Private Sector–Led Economic Diversification and Development in Sudan,” African Development Bank Group, East Africa Regional Development & Business Delivery Office, 2016, pg. 133, accessed 12/19/2017.

- “Sudan Energy Profile: Most Oil Produced in South, But Pipeline, Refining in North – Analysis,” Eurasia Review, October 1, 2011, accessed 10/25/2017. “Petronas Steps Up Petroleum Investments in Sudan,” Petronas Media Release, August 30, 2005, accessed 10/25/2017. John Irish, “Costs delay Sudan refinery eyed by Petronas,” Thomson Reuters, May 27, 2008, accessed 10/25/2017.

- “Sudan & South Sudan Oil & Gas Report Q4 2018,” BMI Research, July 2018 “South Sudan president directs oil minister to speed up work on oil refineries,” S&P Global Platts, July 1, 2016, accessed 10/25/2017.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the World Bank Global Gas Flaring Reduction Partnership, Global Survey of Natural Gas Flaring Database, accessed 3/20/2019.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration, International Energy Statistics Database.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration, International Energy Statistics Database.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration, International Energy Statistics Database.

- The World Bank Group, World Development Indicators DataBank, accessed 3/20/2019.

- “Sudan & South Sudan Power Report Q2 2018,” BMI Research, March 2018. “Private Sector–Led Economic Diversification and Development in Sudan,” African Development Bank Group, Sudan Country Office, 2016, pg. 134.

- “Sudan & South Sudan Power Report Q2 2018,” BMI Research, March 2018.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration, International Energy Statistics Database.

- The World Bank Group, World Development Indicators DataBank, accessed 3/20/2019.

- “South Sudan works to increase electricity supply,” Africa Oil & Power, June 28, 2018.

- “Uganda seals cross border electricity trade deal with S. Sudan,” ESI-Africa, October 6, 2017.

- “Sudan & South Sudan Power Report Q2 2018,” BMI Research, March 2018.

- “Sudan & South Sudan Power Report Q2 2018,” BMI Research, March 2018.