How The 2024 US Presidential Election Could Affect Europe – Analysis

By ECFR

By Célia Belin, Majda Ruge and Jeremy Shapiro

America is changing and US foreign policy is changing with it. For most EU member states, the European alliance with the United States has long been the central feature of their foreign and security policy. But the tumult of the Trump administration and the more polite foreign policy revolution of the early Biden administration have demonstrated beyond any doubt that the old world that America made – and the old bargain that it struck with Europe – will not long persist.

For Europeans, who remain highly dependent on US security guarantees, navigating the turbulent world of US domestic and foreign policy remains a matter of existential importance. Accordingly, European anxiety about a potential Republican president in 2025 is particularly high. The spectre of a return of Donald Trump to power is often raised to argue for greater strategic sovereignty for Europe. This sense of dread naturally inspires curiosity about how the various Republican presidential candidates differ in their foreign policy approaches. Republicans will always define their policy in opposition to an incumbent Democratic administration. But it will nonetheless matter a great deal whether Trump, Ron DeSantis, Nikki Haley, Mike Pence, or some other Republican occupies the White House.

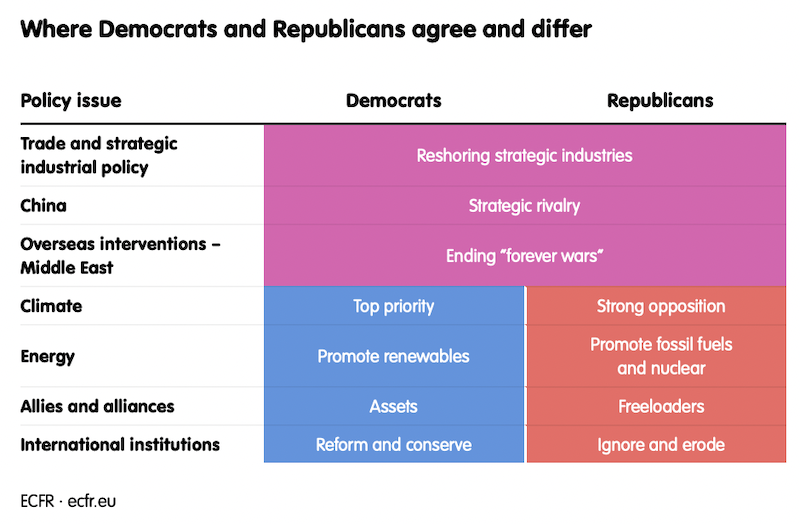

We can expect some continuity in US foreign policy, no matter which party wins the 2024 presidential election. Pressure from the base in both parties in favour of working-class interests has created several overlaps between Republican and Democratic party positions on foreign trade, strategic industrial policy, the US strategic rivalry with China, and overseas interventions. Still, the parties remain hopelessly divided along partisan lines on many important issues. On energy and climate, the utility of allies, and the approach to international institutions, Republican and Democratic foreign policy positions differ vastly. A change in leadership in the White House would thus entail deep swings in policy.

The two parties also have serious internal divisions on foreign policy. On the right, the Trumpian wing of the Republican party sees the war in Ukraine entirely differently from most Republican congressional leaders. On the left, progressive lawmakers have been highly critical of the militarisation of foreign policy that finds widespread support among mainstream Democratic leaders. In both parties, foreign policy ‘tribes’ – have formed, and engage in fierce internal debates over distinct policy approaches. America’s future foreign policy will depend greatly on which group prevails.

This paper explores the similarities and differences within and between the parties on the most important foreign policy areas that affect America’s relationship with Europe. It offers recommendations on what Europeans can do to protect their interests, independent of who sits in the Oval Office in January 2025. Ultimately, it warns Europeans to take the United States’ foreign policy debate seriously – not to ignore it, and to prepare for the profound changes it may bring.

Where Democrats and Republicans agree

A bipartisan consensus has emerged on some foreign policy issues despite the deep polarisation of US politics. Republicans and Democrats are increasingly pushing in similar directions on foreign policy issues that have a strong resonance with white working-class constituencies in swing states. This includes growing bipartisan support for promoting US manufacturing jobs in the face of international competition, efforts to build greater domestic production capacity, and a rejection of overseas military interventions, especially in the Middle East and North Africa.

Foreign trade and industrial policy

Republicans and Democrats are increasingly coming together around a new, less neoliberal vision of the American economy. Traditionally, Democrats have been more sceptical than Republicans about free trade pacts, which they viewed as failing to protect environmental and labour standards. However, faced with a deepening US-China rivalry and a fierce competition for working-class voters in the swing states, the parties are now converging on this issue. Their leaders feel the domestic political need to protect and promote US manufacturing jobs and they increasingly view certain industries and technologies as too important or too strategic to be allowed to go abroad.

Republicans are building on the record of Trump, who disrupted the party’s traditional commitment to the free trade agenda in 2016. To him, US trade policy had trapped America in unfair trade agreements while allies were free-riding on US security guarantees, and enemies were gaining advantage over the US. Pledging to reduce trade deficits and protect domestic industries, Trump imposed sweeping tariffs on enemies and allies alike and withdrew the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which had been set to cover 40 per cent of the global economy. Trump also renegotiated the US free trade deal with Canada and Mexico to create more incentives for car manufacturing to relocate from Mexico to the US.

The Republican party did not return to its pre-Trump consensus after the 2020 election. Overall, Republicans now call for greater government intervention in markets to limit the power of corporations, revive domestic industries, and regain US independence in key strategic sectors. Josh Hawley, a Republican senator from Missouri, now warnsthat, because of neoliberal policies, “thousands of factories have shuttered, millions of jobs have been shipped overseas … and America is dangerously dependent on the productive capacity of China, our chief adversary.”

This view seems to have become common in Washington. The Biden administration has retained the Trump administration’s focus on reshoring and restoring America’s manufacturing capacity. In a speechin April 2023, Jake Sullivan, President Joe Biden’s national security adviser, lamented the impact of America’s neoliberal ideology in the 1990s and 2000s, which pushed overseas “supply chains of strategic goods, along with the industries and the jobs that made them”.

According to Sullivan, the US needs to “forge a new consensus” in favour of a “modern American industrial strategy [that deploys targeted public investments in] specific sectors that are foundational to economic growth, strategic from a national security perspective, and where private industry on its own isn’t poised to make the investments needed”.

Accordingly, under Biden, the tariffs on aluminium and steel imports from the European Union were simply replaced by quotas and voluntary export restrictions; the US did not rejoin the successor to the TPP or show any interest in brokering a free trade agreement with the EU. The Biden administration has instead pursued a targeted strategic industrial policy that subsidises domestic industries in which the US wants to retain an edge; and it aims to reduce dependence on foreign sources, especially China. Several of the major pieces of legislation passed by the Biden administration embody this effort, including the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Whether it is the expansion of domestic preference in procurement or domestic content requirements to qualify for subsidies, the US is on a clear trajectory towards strategic industrial policy and reshoring.

Ending an era of military operations and nation building

Increasingly, both parties reject the idea of military intervention abroad, particularly for the purposes of nation building. From its first days in office, the Biden administration has deprioritised the Middle East and has carefully avoided getting dragged back into the region. The US National Security Strategy, released in October 2022, describes the previous nation building efforts in the region as distracting from the priorities of outcompeting China and constraining Russia: “We have too often defaulted to military-centric policies underpinned by an unrealistic faith in force and regime change … while failing to adequately account for opportunity costs to competing global priorities or unintended consequences.”

That policy course, while messy and at times inconsistent, has been pursued by three successive presidents, as seen with: Barack Obama’s announcement of the full withdrawal of US forces from Iraq in 2011; Trump’s agreement with the Taliban on phased withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan in 2020; and Biden’s withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan, regardless of how his NATO allies felt about it. As Biden’s Afghanistan speech highlights, the decision was more than just to bring the troops home – it was “about ending an era of major military operations to remake other countries”.

Sentiment in both parties is strongly that the era of intervention and nation building in the Middle East is over and the region is no longer America’s priority.

China

There is also a solid bipartisan agreement that China represents the greatest challenge to US national security interests and to the global order. Both the Trump and Biden administrations identified China as the main rival and the top foreign and security policy priority in their respective National Security Strategies from 2017 and 2022. While there are differences between and within the parties in how they see the nature of the Chinese military threat and ways to deal with it, the ambition to prevail in the US-China strategic rivalry will drive America’s foreign policy regardless of which party wins the presidency in 2024.

This consensus is strongly pronounced in the economic realm, where both parties are focused on succeeding in the technological competition with China. The Trump administration imposed tariffs amounting to $350 billion on Chinese imports and introduced restrictions on exports of advanced technologies to China. In 2018, Congress, working on a bipartisan basis, expanded the powers of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States to review and block Chinese investments. The Biden administration has built on Trump-era policies and passed additional restrictions under the Foreign Direct Product Rule, which prevents companies from, for example, selling items to Huawei that contain US technology or software without previously obtaining a US licence. Similarly, measures for strengthening US competitiveness in semiconductors as well as in green technology are aimed at helping the US in its rivalry with China.

Despite intensifying internal debates on the security challenge posed by China, the US commitment to Taiwan’s security is largely bipartisan. Voices in both parties stress the urgency of bolstering the US capacity to deter a Chinese attack on Taiwan. The bipartisan Taiwan Policy Act of 2022, introduced by Senators Bob Menendez and Lindsey Graham, was a comprehensive attempt to strengthen US diplomatic and military tools to deter potential Chinese aggression against Taiwan.

Beneath this broad agreement, there remain important differences in how the parties see the role of allies in the US-China competition. A future Republican president would likely take a more unilateral approach towards China, penalising European allies if they do not play along. Any future Republican administration will be more transactional in its relationship with the EU and will make its trade policies vis-à-vis Europe dependent on the EU’s strategic industrial policy on China. The current Republican frontrunners are also more likely to push for a faster redeployment of military resources away from Ukraine to the Indo-Pacific. In the event of a second Biden administration, the US is more likely to continue to engage allies to contain China, even if the administration’s patience may eventually wear thin. But, in any event, the US will increasingly expect the EU to align its strategic industrial policy on China with that of the US, while demanding greater European contributions to military and security matters in Ukraine, in order to free up US military resources for the Indo-Pacific.

Where Democrats and Republicans differ

Not all Europeans worry about the risk of Trump, or a Trump-like candidate, being elected in 2024. Quite a few European leaders even enjoyed the former president’s style, or at least were able to accommodate themselves to it, and were rewarded with visits or a nice tweet. European diplomats, in our experience, see both Republicans and Democrats as having their quirks, but ultimately believe they can and must work with both. Republicans lay out their interests more clearly, which makes negotiations more straightforward, although they can also be more unpredictable in their actions. Democrats are less brutal and more predictable, as well as more likely to respect previous engagements.

Therefore, if Europeans can adapt to any US president – and if there is a national consensus emerging in favour of defensive trade policies, against military interventions, and for competition with China – then perhaps it does not matter who sits in the White House.

Alas, there are at least four areas where it would matter a lot to Europeans whether 2025 opens to a second Biden administration or a second Trump(ian) administration.

Energy and climate

Few foreign policy topics are as divided along partisan lines as the issue of climate change. The election of one leader or another is likely to shift the needle entirely on this topic.

Since taking office in January 2021, the Biden administration has made several strides towards tackling the climate crisis: rejoining the Paris climate agreement, appointing former secretary of state John Kerry as the first special presidential envoy for climate, hosting the leaders summit on climate, and adopting new ambitious targets for reducing US greenhouse emissions and achieving a net-zero economy by 2050. The Biden administration doubled down with its IRA, a $737 billion piece of climate legislation that creates subsidies and tax credits for investment in clean energy technologies, such as electric vehicles and batteries, hydrogen, energy storage, and electricity transmission, and to diversify these strategic supply chains away from China. If re-elected, Biden will push for allies and partners to follow America’s lead on the IRA and subsidise the energy transition in their own countries or regions, transforming their economic model in favour of renewable generation and energy efficiency. Driven by its objective of domestic renewal to compete with China, climate-friendly investments and technology competition will continue.

No congressional Republicans voted for the IRA, even though it will direct billions in subsidies to many Republican congressional districts. Over the past decade, shale gas and offshore technologies have revolutionised the American energy sector, and transformed the US from an energy importer to the world’s top oil and gas producer and a leading exporter. Alongside this, Republicans came to believe that climate legislation kills jobs, and that it erodes America’s competitiveness, particularly vis-à-vis China. Since the days of vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin in 2008 chanting “Drill, baby, drill”, support for oil and gas extraction has been massive in the Republican party. Today, there is a 56-point difference between the support among Democrats who believe climate change should be given top priority as a foreign policy goal (70 per cent) and support among Republicans in favour of the same (14 per cent). It is the foreign policy issue that most divides the two parties.

Accordingly, any incoming Republican administration in 2025 is highly likely to take a different course. With wide support from the base, a Republican president would renew Trump’s pro-fossil fuel policy. Among the tools at that president’s disposal will be deregulation in favour of oil and gas, increased numbers of drilling permits, the dismantlement of the Environmental Protection Agency, and the provision of tax incentives for the oil and gas industries. Internationally, a Republican White House would ally with fossil fuel producers and promote fossil fuel exports with new partners in the global south, as well as with Europeans.

International institutions and cooperation

“America is back, diplomacy is back” was Biden’s message in his first major foreign policy speech as president. The previous four years of Trump’s “America First” policy had seen the US quit a host of international organisations and agreements and participate in the erosion of international institutions. The Biden administration has worked to reverse this trend, re-entering many of these agreements, although it was unable to salvage them all, including the nuclear deal with Iran. It has also tried to form new diversified partnerships in sub-Saharan Africa and south-east Asia, making offers to promote economic opportunity, expand energy access, and increase connectivity, with the aim of regaining a footing in an increasingly contested world. With the Summit for Democracy, Biden linked America’s internal struggles to the larger ideological competition with authoritarian countries.

However, increased competition with China and the war in Ukraine continue to erode multilateral frameworks of cooperation, while the global south has become increasingly transactional. Any future US administration will have to contend with the rapid transformation of the world order, which risks rendering international organisations ineffective or antagonistic to Western interests. Faced with this challenge, a Democratic or Republican administration would likely take different approaches.

If re-elected, Biden would continue to work to shape the system, with the end goal being to reform but ultimately conserve it. For example, although Treasury secretary Janet Yellen opened the door for World Bank reform to secure more resources for energy and climate transition, the US is unlikely to agree on amending the institution’s fundamental decision-making structures. Because Democrats view international institutions as an opportunity for leverage, a Democratic president would have little incentive to cede influence within them to China.

A Republican administration, by contrast, would be unlikely to invest time and effort in regaining influence in these arenas. Unwilling to let themselves be bound by international agreements, a Republican president would focus on negotiating new bilateral or regional agreements. Trump would renew his deal-making ambitions, perhaps even succumbing to the temptation to seek a negotiated solution between Ukraine and Russia. Meanwhile, Republicans will focus on the US being able to maintain its military advantage and shunning arms control negotiations.

Not coincidentally, each party’s political base agrees with the instinct of their leaders. Republicans are 30 percentage points more likely than Democrats to say that getting other countries to assume more of the costs of maintaining world order should be a top priority for US foreign policy (56 per cent v 26 per cent). More generally, Democrats believe in international cooperation, with a large majority viewing global challenges (such as refugees and infectious diseases) and global cooperation (strengthening the United Nations) as priorities for US foreign policy. Meanwhile, Republicans believe in increasing defence spending.

Allies and alliances

Biden believes in the value of allies and alliances in strengthening America’s position as a global leader. Since taking office, he has carefully managed and invested in relationships with European, Canadian, and Asian allies that share his views on democracy, competition with China, and countering Russian aggression. Nevertheless, his administration has at times failed to take foreign policy decisions collectively, such as the retreat from Afghanistan or the formation of the AUKUS alliance, which alienated France. America’s strategic investments in its high-end and green technology industry (with its CHIPS Act and the IRA) have caused friction with Europeans who worry about the long-term consequences of the US gaining such a competitive advantage and skewing the rules of global trade in its favour. As the EU loses economic and military ground to the US and the security situation in Europe worsens, the risk of vassalisation is growing.

In contrast to Biden, Trump openly vilified traditional US alliances, cheered on the prospect of additional member states leaving the EU after Brexit, and at times betrayed allies, as the Syrian Kurds experienced in 2019. He cultivated an affinity with nationalist, conservative strongmen, and authoritarian figures, from central and eastern European and Arab state leaders to Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong-Un. Trump’s return would only embolden them. Trump also made no mystery of his annoyance with allies that, in his view, cost the US money to defend and competed with America for market share. His scepticism fixed in Republican minds the idea of allies as free-riders on American security and established a consensus within the party base that NATO allies should pay up for their defence. Germany in particular, a favourite scapegoat of the Trump administration, would remain a target.

Current Republican leaders, such as Ohio senator JD Vance and Florida governor Ron DeSantis, continue to disparage allies for their lack of investment in defence. American spending on the war in Ukraine will be scrutinised in light of how much Europeans are contributing. Imbalances may be used to justify further disinterest in the region and rebalancing towards Asia. Even in Asia, most Republican leaders would ask American allies for greater contributions to regional security. For instance, despite Japan’s recent significant increases in military spending, some Republicans continue to see it as too little. By contrast, a more restrained second Trump administration would introduce new uncertainty about America’s commitment to the defence of Taiwan and treaty allies in Asia. Taiwan would risk becoming a bargaining chip in US trade negotiations with China.

Debates within the parties

Both parties have embraced a foreign policy of competing with China, limiting engagements in the Middle East, and focusing on industrial renewal. Republicans push for energy dominance and breaking free of entangling multilateral institutions and alliances. Democrats are united on climate action, building alliances, and leading international institutions.

However, each camp also experiences profound divisions on some key aspects of foreign policy. The Republican party in particular remains deeply split on the use of force and on the importance of US global leadership. Meanwhile, Democrats disagree on the military build-up in the competition with China and are split on the use of US coercive power. The internal tribes that have formed around these issues will shape the foreign policy of the next administration and, at the very least, constrain the choices of the next president.

Republican divisions

Three main Republican foreign policy tribes are emerging and competing for the mind of the next Republican president. These are: the restrainers, the prioritisers, and the primacists.

All three tribes begin from accepting the Trump-era inheritance on domestic policy and applying it in the international arena. This includes the anti-‘wokeness’ agenda, the demand for a much more restrictive immigration policy, and a belief that the US has suffered economically and culturally from globalisation. Such stances suggest that any potential GOP president will: reverse the current administration’s efforts to combat climate change and expand investments in the fossil fuel sector; express the antipathy towards free trade inherited from the Trump era; and maintain the focus on the rivalry with China.

But, beyond this core, the tribes, and the potential leaders of the next US administration, differ over the nature of the United States’ role in the world, the attitude toward allies and alliances, and the commitment to European security and the war in Ukraine.

Restrainers

The ‘restrainers’ in the party advocate strength at home and restraint in deploying and using military force abroad. Hardcore restrainers such as Senators Rand Paul and Mike Lee support fewer commitments for the US abroad and disentanglement from US alliances, including NATO. Along with prominent Trump advisers such as Steve Bannon and Richard Grenell, they advocate reducing US assistance to Ukraine. Restrainers are currently a minority within the Republican party elite, but their positions reflect the views of the Republican base that it is not America’s job to defend wealthy European nations from Putin, and that US tax dollars would be better spent on building a wall to stanch the “spiraling tsunami” of immigrants at the United States’ southern border.

The restrainer camp, whose foreign policy discourse is shaped by current and former allies of Trump – including Bannon and Grenell as well as television presenter Tucker Carlson – often likes to consider Trump one of their own. However, during his presidential term, Trump demonstrated only a very fickle adherence to this tribe. At times, he declared he would withdraw US forces from Syria and Afghanistan, and even end US membership of NATO – before failing to do any of these things, while at times threatening interventions in Iran and North Korea. On Ukraine, he has insisted that Biden is leading the US into world war three and declared that, once back in the White House, he would end the conflict within 24 hours. Overall, Trump continues to espouse a more restrained foreign policy than any other post-cold war US president, but his inconsistencies allow each tribe to imagine he might be a member.

Prioritisers

For those Republican foreign policy thinkers who want to maintain a forward presence in the world, the key split is over the priority to give to China. The ‘prioritisers’ see the strategic challenge that China presents to the US as profound and existential. Like the restrainers, they emphasise that US resources are limited, but they feel that the Chinese threat requires a forward response on a par with the American effort against the Soviet Union. They worry that US attention and resources devoted to other, less critical theatres such as Europe and the Middle East will sap US strength for the coming battle with China.

Republicans such as Josh Hawley, Ohio senator JD Vance, and Elbridge Colby, former deputy assistant secretary in the defence department, see the intensity of the US competition with China over Taiwan as producing two inevitabilities: a military confrontation with China over Taiwan and a US withdrawal from Europe and the Middle East. They insist that the scale of the China challenge means that the US does not have a two-war military capacity. Senator Hawley voted against NATO membership for Sweden and Finland as well as against continued military support to Ukraine, arguing that America is overstretched and unable to defend its more important ally Taiwan.

Ron DeSantis remains difficult to categorise, but he gave the prioritisers hope that he might be one of them when in March 2023 he declaredthat, “[w]hile the US has many vital national interests … becoming further entangled in a territorial dispute between Ukraine and Russia is not one of them.” He specifically cited China as one of the reasons that the US should avoid further involvement in the “dispute” between Russia and Ukraine. DeSantis begins the foreign policy chapter of his recent book with “The Chinese Communist Party represents the most significant threat – economically, culturally and militarily – the United States has faced since the collapse of the Soviet Union.”

Primacists

The ‘primacist’ camp believes that Washington can and must maintain US leadership and military presence worldwide. It includes individuals such as Nikki Haley, Mike Pompeo, John Bolton, and Mike Pence, establishment figures who all joined the Trump bandwagon and served in his administration. The primacists were against the withdrawal from Afghanistan. They see Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as a direct consequence of that withdrawal, which they believe signalled American weakness. They thus argue that the US must stay engaged and maintain a strong deterrent posture not only in Asia but also in Europe and the Middle East. They do not accept the idea that the US lacks the resources to maintain global leadership, but they do acknowledge that doing so will require America’s allies, particularly in Europe and east Asia, to contribute more to global security challenges.

Democratic divisions

Three tribes are also emerging on the Democratic side: leaders, realists, and progressives will shape Biden’s foreign policy, should he be re-elected.

Foreign policy divisions among Democrats are less stark than those tearing apart the Republicans, in part because of the Democrats’ political imperative to support the president. When a group of 30 progressive lawmakers published a letter to Biden urging talks to end the war in Ukraine in October 2022, they retracted it just three days later. With Biden now officially running for re-election, the party has mostly united behind a strategy of trumpeting the successes of the president’s first two years. Democratic lawmakers have thus rallied behind the president to support Ukraine; they have backed his choices to retreat from Afghanistan; and they have endorsed the Biden administration’s “foreign policy for the middle class”, through large climate and industrial legislation.

Nonetheless, increasingly visible foreign policy divisions lurk beneath the surface of this Democratic unity. The following three tribes represent broad groupings of lawmakers and experts who rally around certain instincts and approaches.

Leaders

A substantial portion of the Democratic party – inheritors of the cold war internationalism tradition – continues to believe in America’s role as a guarantor of world order. They believe that the US must assume a leadership position, stay focused on its alliances, and push back against revisionist powers – Russia and China foremost. Along with Biden, this group includes individuals such as Senator Bob Menendez, chair of the foreign relations committee, Senator Dick Durbin, chair of the Senate Ukraine Caucus, and former intelligence officer Congresswoman Elissa Slotkin, who calls herself a “believer in a strong American leadership in the world”. The members of this ‘leaders’ tribe express strong support for NATO and they back Finnish and Swedish NATO membership. They are also highly focused on building up Asian alliances: the Quad, AUKUS, US-Japan-ROK, and US-ASEAN are all now cornerstones of American strategy in Asia.

On Ukraine, the leaders are focused on imposing a strategic defeat on Russia. In the words of Congressman Seth Moulton, “any weapon should get to Ukraine; there is no negotiating with Putin; he must be stopped or another NATO country is at risk.” The same goes for China: the leadership tribe encourages the administration to do more in Ukraine in order to send a message to China. Senator Menendez, for example, advocated “clarity in word and deed” on Taiwan after Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s trip to the island, in contrast with the decades-long US policy of strategic ambiguity on Taiwan.

Realists

As the war in Ukraine has reinforced the leadership tribe, a more ‘realist’ tribe has begun to emerge. This loose group is more prevalent in think-tanks than in Congress. Its members believe American power is limited, that the international system is moving inexorably towards multipolarity, and that the US should focus primarily on vital interests while leaving allies and partners to take up more of the slack.

Realists are wary of military entanglements and viewed the Afghanistan withdrawal as a necessary, long-overdue decision. Senator Chris Murphy, a member of the US senate foreign relations committee, has spoken in favour of sunsetting future authorisations for use of military force after two years, in order to place a check on the interventionism of the executive branch. Realists pay close attention to military strategies that may drag the US into future conflicts and they denounce rhetoric that, in their view, increases the risk of US-China conflict over Taiwan. For Senator Brian Schatz, who voted against legislation intended to boost Taiwan military defences, these efforts offer Taiwan “symbols of sovereignty” that “may irritate the Chinese”.

On Ukraine, realists are focused on finding an exit. They are ready to support negotiations when conditions are appropriate, even if Ukraine may have to make territorial concessions – ultimately, they believe that Russia will have learned its lesson by paying a price for these concessions. Realist think-tank experts have made the case for caution and diplomacy and warned of the risk of a long war.

Realists advocate the use of sanctions, or even economic warfare, as elements of integrated deterrence, but also anti-corruption and anti-kleptocracy legislation as ways to undermine the strength of authoritarian powers. They believe in the rules-based order as a means to constrain actors and build global consensus. Similarly, climate-friendly policies are to be used to constrain revisionist power. As Senator Ed Markey puts it, “we can destroy the business model of Russia and of Saudi Arabia if the West goes to all-electric vehicles.”

Progressives

‘Progressives,’ by contrast, believe that American power is too militaristic, supports oppressive regimes, and has to be redirected. With deep roots in the Congressional Black Caucus and in trades union activism, progressives care about social and racial justice and advancing the working class. In domestic as in foreign policy, progressives are pro-poor, pro-minorities, pro-immigrant, pro-LGBTQ, and pro-worker. For many of them, such as Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the US should lead a climate-focused foreign policy that would tackle climate change as a source of poverty and migration in the global south. Others, such as Congressman Ro Khanna, believe the US should seek to become once again a global manufacturing superpower.

Progressives are committed to the defence of Ukraine, which they view as the victim of a war of aggression. They voted largely in favour of economic assistance, although several of them opposed increased military aid. In the long term, progressives worry about nuclear escalation and the use of offensive weapons. They lament the over-militarisation of foreign policy in general and believe that the US is pushing to a military build-up in Asia through AUKUS and other military agreements. A small group of members of Congress, called the Defense Spending Reduction Caucus, are pressing for a reduction in the military budget, and for some of this to be redirected towards social programmes at home. In early 2023, the caucus’s co-chairs, Representatives Barbara Lee and Mark Pocan, argued for $100 billion of the Pentagon’s budget to be slashed.

How Europeans can survive the US election

This fervid US foreign policy debate means there is great uncertainty and risk for Europeans in the US presidential election. They cannot vote, but they can prepare.

The first and most essential way to prepare is to admit you have a problem. Traditionally, the European approach to any new US presidential administration, even evident after Trump’s election in 2016, is to scramble to establish contacts with the personnel of the new administration. In a desperate attempt to mitigate the cost of a political transition to a President DeSantis or Trump, European diplomats may be tempted to rush to find common ground with the new masters – filtering out the uncomfortable messages. Instead, Europeans needs to listen closely to US foreign policy debates and believe what the candidates say.

The war in Ukraine is a case in point. Despite the growing opposition to US involvement in Ukraine among the Republicans, too many decision-makers in Europe continue to dismiss the trends in the Republican party as limited to fringe groups. European leaders still tend to interpret the positions of the primacists among the congressional elite as representative of the party and the next Republican administration. For example, in his March 2023 visit to Washington the prime minister of Poland, Mateusz Morawiecki, essentially dismissed the stances of DeSantis and Trump as political “poker games” and insisted that the views of Republican primacist senators remain prevalent. But the positions of the congressional elite sharply diverge from those of the two frontrunners in the GOP primaries and of the Republican base. Failing to take the US debate seriously will not make it go away.

European leaders need particularly to prepare for shifts in other areas of US foreign policy that a new Republican administration may bring about, even beyond Ukraine. These include the abandonment of international cooperation on climate action and renewable energy; disdain for international institutions and the liberal democratic order; lower tolerance for shortcomings in European military capabilities and strategy; greater affection for populist conservatives such as Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orban; and a more transactional approach towards traditional allies in Europe that will result in higher levels of coercion and stronger linkages between policy areas.

A continuation of the Biden administration would, by definition, mean much less change in US policy towards Europe, but it would still present challenges. The foreign policy debates within the Democratic party will have less of an immediate effect on a second Biden term, but over time we can expect them to weigh on a Democratic president. The realist tribe will grow stronger if the war in Ukraine continues to take resources away from other more pressing priorities, particularly a possible contingency in Taiwan. The progressive tribe is increasingly capturing the base of the party and so its influence will grow as the next generation of Democratic leaders position themselves to take over from Biden. We can thus expect these alternative perspectives to slowly gain influence over the new course of a second Biden term. And should the Democrats lose the election, these tribes will gain influence even more quickly in opposition.

Responding to either of these challenges will be difficult for European states that are so dependent on America. The US, with its strong relationships with most European countries, retains a much greater capacity to divide the EU than Russia or China do. If the bitter splits over the role of the US in Europe persist, none of the other strategies to protect European interests will work. Any US administration will simply use these divisions to ensure its policy preferences are protected. As with almost any element of European foreign policy, an essential requirement is achieving greater unity – not only to deal with a potentially more distant or disruptive America, but also to confront an increasingly assertive China.

Beyond those core approaches, European leaders may want to consider the following strategies.

Build climate coalitions and leverage European power in trade. In contending with a Republican administration, the EU should seek to impose costs on the US for non-cooperation on climate goals. Building coalitions around the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) could be an effective way to incentivise a Republican administration into cooperation on climate goals. This could be done first by strengthening climate diplomacy with like-minded countries (such as Canada, Japan, and South Korea), as well as with countries such as China, India, and Brazil, which account for a substantial part of global emissions and global trade. Together with these nations, the EU could form a “global climate club” that would rely on economic incentives and regulations such as the CBAM to coerce the US into returning to cooperation. At the same time, the EU could proactively engage the US business community, industry associations, and state governments to build a coalition of supporters for global climate goals and highlight the economic benefits of climate action. The ultimate aim would, of course, be to bring the US into that climate coalition eventually. Some of our ECFR colleagues have explained in more detail how to create such coalitions.

Move towards a more autonomous European defence capability. The war in Ukraine, security challenges in the Middle East, and the US disengagement from less relevant theatres to focus on China all mean that the EU needs to quickly mature into a sovereign foreign and security policy actor, capable of acting independently in security and defence affairs. The case becomes even more compelling if a Republican candidate wins the election. The next Republican president is likely to regard the current levels of assistance to Ukraine as conflicting directly with domestic priorities or the goal of deterring a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. In such a scenario, Europeans would be expected to take the lead in dealing with Russia, and would find themselves left to support Ukraine on their own.

In a second Biden term, by contrast, the administration would want to achieve the pivot to Asia that the war in Ukraine slowed down and may be amenable to accepting greater European autonomy. Biden has argued for “the importance of a stronger and more capable European defense” as a benefit to overall transatlantic security. If Europeans were to develop more independent capabilities, Biden, under increased pressure within the Democratic party, might be inclined to support them.

Under any circumstances, a militarily dependent Europe will be more vulnerable to US pressure to align with America’s dictates in other critical fields. Our ECFR colleague Camille Grand has outlined how to at least begin what would certainly be a generational project.

Develop an independent capacity to support Ukraine in the long war. As part of that autonomous capability, Europeans need to hedge against a reduction in US support to Ukraine. The idea that the wealthy nations of Europe cannot take the lead in countering aggression on their own continent, when all EU members (except possibly Hungary) agree that such an effort is necessary, is a startling testament to Europe’s strategic inadequacy. Some of our ECFR colleagues, including one of us, have suggested a plan to support Ukraine that contains four essential elements: long-term military assistance through a new security compact; security assurances in the case of various conceivable Russian escalations; economic security efforts that would provide financial assistance and begin the long reconstruction process as part of a “partnership for enlargement”; and energy security measures that would integrate Ukraine more tightly into EU energy infrastructure. The EU, its member states, and the United Kingdom should pursue these measures and work together to achieve them.

Manage US disengagement in the Middle East and North Africa. Europeans will also need to pick up the pieces in the Middle East as America retrenches. The US risks leaving behind a region home to armed conflicts, political instability, failed or weak states, and waves of refugees seeking sanctuary in Europe. The Europeans will be increasingly responsible for protecting their own core interests there – whether on peace and security, energy security, migration, or counterterrorism. This will require a more integrated and coordinated foreign policy and enhanced military capabilities, and a more strategic approach to engaging with the regional powers that are increasingly turning towards China and Russia. Our ECFR colleagues have produced some suggestions for the European strategy in the region in the light of US retrenchment, elaborating on how Europeans can act as credible security partners there.

Find a voice in strategic economic policy through a geo-economic NATO. The US-China rivalry puts Europeans in a difficult position. The US expects Europe to align with its geo-economic efforts aimed at China – whether on export controls, investment screening, or strategic industrial policy. Recent debates over 5G and green technology subsidies show that the struggle with China will penetrate deeply into the Western domestic sphere and will securitise questions that heretofore have been purely economic. Indeed, in the coming competition between the China and the West, the geo-economic realm will likely become the central front. If Europeans wish to preserve a voice on these questions, they will need a forum in which the US and Europeans can jointly consider the geostrategic implications of economic issues such as industrial policy. A ‘geo-economic NATO’, as suggested by one of us and our ECFR colleague Jana Puglierin, would allow the transatlantic partners to think strategically about geo-economic issues and decide jointly on foreign economic policy, rather than Europeans just accepting US decisions.

Build multilateral coalitions to address real world problems.As noted, a Republican administration is likely to be hostile to various international institutions that are important to the EU, including the World Trade Organisation and the World Bank. A second Biden administration would take a less ideological approach, but nonetheless would increasingly demand more effective action from international institutions as the price of its continued support. Given the EU’s investment in the multilateral system, the bloc needs to hedge against the worst and prepare to capitalise on the best by seeking new coalitions within international institutions that can address real world problems that matter to both Americans and Europeans. Our ECFR colleagues Anthony Dworkin and Richard Gowan have proposed how to do this in four areas: international trade, migration, human rights, and the multilateral regulation of new technologies. These coalitions would usually include the US but might in some cases need to operate without American participation.

None of these policy interventions is easy – they all entail difficult internal European negotiations and painful compromises. The EU, like most complex democracies, has never excelled at long-term planning or strategic hedging. So, it seems that the most likely response to the US presidential election is to worry quietly and hope loudly. Hope, alas, is not a strategy. The two parties and the various tribes within them present very distinct problems for Europeans. Europeans need to prepare for the best as well as for the worst.

About the authors

- Célia Belin is a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations and head of its Paris office. She is a former visiting fellow at the Center on the United States and Europe at the Brookings Institution, in Washington, DC, and she briefly served as the interim director of the Center in 2022. She also served as an adviser on US affairs in the policy planning unit (CAPS) of the French foreign ministry between 2012-2017.

- Majda Ruge is a senior policy fellow at the European Council of Foreign Relations in Berlin. Between 2017-2019, she was a research fellow at the Foreign Policy Institute, School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University in Washington, DC.

- Jeremy Shapiro is the director of research at the European Council on Foreign Relations and a non-resident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. He served at the US State Department between 2009-2013.

Source: This article was published by ECFR

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank each other for their patience, cooperative spirit, and lack of violence in writing what was at times a contentious paper. If a French person, a Bosnian-German, and an American can come together in writing about US politics then surely there is hope for bipartisanship in America. We would also like to thank Mark Leonard for his inspiration, Susi Dennison for her sage advice, Susannah Foussard for her able leadership and encouragement, Adam Harrison for his patient and diligent editing efforts, Nastassia Zenovich for her graphical genius, and Donald Trump just for being himself. None of these people (except Donald Trump) bear any responsibility for any errors that may have crept into this paper