Japan’s Forthcoming Election And Abe’s Political Dilemma – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

By K. V. Kesavan

On July 10, Japan goes to polls to elect half the members of the House of Councillors, the Upper House. In the Japanese legislative structure, the Upper House is less powerful than the House of Representatives, though both are elected directly by the voters. Members of the House of Councillors are elected for a period of six years and one half of the total 242 members face election every three years.

Though less powerful than the Lower House, the House of Councillors still has an important role to play. It can considerably delay the passing of laws if the ruling party does not enjoy majority strength in it. This was seen particularly after 2000 leading to what was known as the “divided Diet”.

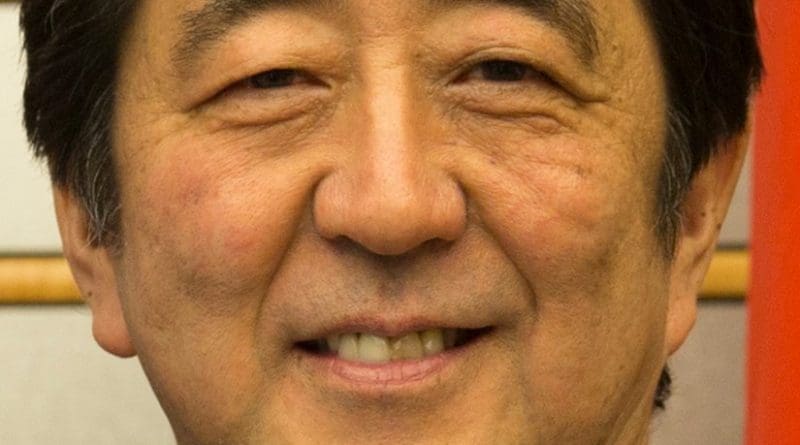

Since the Upper House election takes place once in three years and that too in between the Lower House elections, its outcome is considered as a mid-term assessment of the government’s performance. It provides a reality check on the pulse of the electorate. In 2007, during the first tenure of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, the ruling LDP-Komeito coalition performed very poorly in the Upper House election which accelerated the fall of the Abe cabinet.

On the contrary, in the July 2013 Upper House election, the same coalition scored an impressive victory, gained a commanding majority in the House and consolidated the position of the government. The present election is the second Upper House election Abe faces since his return to power in 2012. Most media surveys indicate that the ruling LDP-Komeito coalition will be able to secure a comfortable majority. But what the coalition seeks to achieve is a two thirds majority which would enable Abe to propose an amendment to the constitution.

Though the Prime Minister has always strongly advocated the need for amending Article 9 of the constitution, this time he has shown considerable caution to keep the focus away from that issue. In fact, the ruling coalition’s election campaign has been marked by a conspicuous absence of references to constitutional revision. The reasons for this are not far to seek. Recent public opinion polls consistently showed popular opposition to constitutional revision. Secondly, LDP’s ally Komeito has always shown its resistance to amending Article 9 of the constitution. Abe has therefore chosen to consider the present election as a “referendum” to know from the electorate whether he should continue to pursue his economic policies further. He also seeks an endorsement of the electorate for his decision to delay the second hike of the consumption tax from 8% to 10 % until 2019. He states that this delay is intended to prevent the global economic showdown from upsetting his efforts to eliminate deflation. According to Abe, “This is an election to decide whether we will forge ahead strongly with economic policies or return to an era of darkness and stagnation.”

But the opposition parties expectedly consider Abe’s postponement as a clear admission of the failure of Abenomics to deliver. Abe, however, counters their criticism by citing significant increases in the country’s tax revenue as well as in the creation of new job opportunities.

As for the nature of the present election, it is necessary to take note of three important changes that have occurred recently and it is too early to say whether they will have any impact on the outcome of the polls.

First, the election law has lowered the voting age from 20 to 18 and this will enable about 2.4 million young voters to exercise their franchise for the first time. In order to woo the young voters, political parties have come out with such proposals as reduction in educational expenses, better employment opportunities and higher minimum wages. Second, under pressure from the judiciary, the government has also redrawn electoral boundaries to avoid glaring disparities in the value of votes between constituencies. The Supreme Court had earlier declared the 2013 Upper House election as “a contest conducted in a state of unconstitutionality.” Under the new system, several modifications have been made to ensure a proper balance in the distribution votes among constituencies. Third, a certain degree of realignment of political forces has taken place on the eve of this election. Even in January this year, realising the need for fighting the ruling coalition in a united way, the main opposition Democratic Party and the New Innovation Party got merged to form a new party called the Democratic Party (Minshinto). In addition, for the first time in Japan’s post-war politics, the Japan Communist Party (JCP) will cooperate with other opposition parties including the Democratic Party in fielding common candidates in the 32 single member constituencies in order to avoid dividing their votes. Both the LDP and the Komeito have understandably criticised this ‘unholy’ electoral understanding. It is well-known that these 32 constituencies have been the real source of LDP’s electoral strength.

The LDP-led coalition is already having 84 uncontested seats in its tally and in the present election, it needs to win 78 seats out of the 121 seats up for the grab to reach the magic number of 162 which is the 2/3 majority in the House. If this happens, the ruling coalition, with its 2/3 majority strength already in the House of Representatives, could initiate a proposal in the Diet for amending the Constitution.

Understanding this situation, the opposition parties, mainly the Democratic Party under Katsuya Okada, are showing their utmost determination to stop Abe from capturing 78 seats. They perhaps do not mind Abe winning a simple majority by securing 38 seats. But considering the intensity of the campaign carried by the ruling coalition and the weaknesses of the opposition, one should not be surprised if the LDP coalition manages to secure 2/3 majority in the Upper House.

In such a scenario, will Abe be in a mood to immediately embark on his initiative for a constitutional amendment? Many analysts and commentators believe that Abe will be politically prudent not to show any haste in pushing his pet political goal. He knows that mere numerical strength in the Diet alone is not enough, because any proposal for constitutional change will have to be endorsed by the people in a national referendum. Apart from opposition leaders who are vehemently against constitutional amendment, even Abe and many party colleagues are not confident about the outcome of a national referendum. Further, the Komeito, LDP’s trusted political ally, has many reservations on the question of amending Article 9 of the Constitution. There is a strong belief across the political spectrum that a national consensus on the issue is still evolving and that more persistent efforts are needed to prepare the nation for such a major constitutional turning-point.

This author does not address what Abe proposes to change via constitutional amendment. I believe it relates to the US desire for Japan to rearm itself so as to give added weight to the US plans for its “pivot to Asia” which aims to ‘contain’ China. Enlisting Japan in this “pivot” will simply strengthen the already considerable tension in the S. China Sea. Put into the context of the current US/NATO push to provoke Russia by running military exercises right on its border and activating the Roumanian ABM “missile shield” aimed at Russia, the US is laying the foundation for WWIII. US Russia/China experts are warning, as they have warned for some time, of the dangerous consequences of the US for military/economic hegemony over the entire planet and its remaining resources.