Self-Immolations In Tibet: The ‘Neutral Stance’ On A Political Instrument – Analysis

By IPCS

By Bhavna Singh

A series of events necessitates revisiting the Tibetan self-immolations issue – from the resignations of Lodi Gyari and Kelsang Gyaltsen, (the primary envoys for the Dalai Lama in negotiations with the Chinese authorities), the 77th birth anniversary the 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, his ‘neutral stance’ on the self-immolations issue and the repetitive condemnation of such incidents as ‘splittist’ activities by the Chinese government.

This article explores the rationale for self-immolations and what have been the responses of the Dalai Lama and the Chinese government?

The Tibetan Rationale

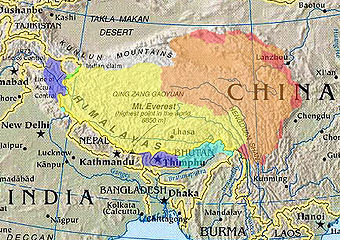

Repeated calls for ‘meaningful autonomy’ by the Tibetans and demands of religious and personal rights have been constantly disregarded by the Chinese government. Tibetans all over the world, especially from across Europe have been pushing for a “strong” resolution on China’s human rights violations in Tibet at the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) session in Geneva (held June-July 2012) but to no avail. Self-immolation seems to be the primary responsive strategy of the Tibetans, undertaken as a strategic effort directed towards political goals; in this case, the return of the Dalai Lama to his birth place and not simply as the product of irrational individuals or expression of fanatical hatred (towards the state). The aim is to compel the Chinese government to change its policy decisions on Tibet and acknowledge the desperation amongst Tibetans.

Despite the lack of alternative political means for the Tibetans, self-immolation does not seem to be evoking a positive response from a hardnosed Chinese state. The testimonies of the special envoys, who were compelled by the deteriorating situation inside Tibet to resign substantiate the fact that the China’s United Front (CUF) did not respond positively either to the Memorandum on Genuine Autonomy for the Tibetan People presented in 2008 or its note in 2010. In fact, there was an indication towards abrogation of the minority status itself to remove the basis for autonomy. Such rejoinders by the Chinese government have forced the Tibetans into desperation and subsequently in the renewal of their long-suppressed demands.

Why is the Dalai Lama Silent on Suicides?: Deconstructing his Neutral Stance

Recent statements by the Dalai Lama reflect the conundrum he faces being the spiritual leader of the Tibetans. He had voiced strong faith in the people and their political maturity during the elections to the Tibetan Government–in exile (TGIE) last year; however, the current events indicate the peripheral nature of that political transition. In a recent interview, he was quoted as saying “now, the reality is that if I say something positive, then the Chinese immediately blame me… If I say something negative, then the family members of those people feel very sad and thus the best thing is to remain neutral” (The Hindu). Even if he chooses to stay neutral the Chinese government is likely to interpret his gestures according to their own convenience, rather by staying mum, he is leaving it to the individual interpretation of the Tibetan monks to construe their own ‘altruistic gestures.’ Thus, at a time when the need for direction is an absolute imperative for these Tibetans, his reluctance to take a stand reeks of leadership subversion.

While Tibetans are fighting to get him back home, he has chosen to make a ‘politically correct’ statement rather than endorse the cause that he had been fighting for so long. This might serve his personal image consciousness as a politician but does not augur well for the Tibetan movement. Despite the devolution of the political authority the Tibetans still look for guidance from him and are increasingly concerned about the reincarnation of the next Dalai Lama. Orphaning the movement at such a time will prove fruitless even if it is done with the intent to let the younger generation (the new Kalon Tripa) take control of the situation. It will certainly not be enough to merely acknowledge a dilemma arising from the violent acts of an increasingly frustrated younger generation (Of the 31 self-immolators who died seven were monks, nine former monks and two nuns) of Tibetans in China and in exile, as this might further confuse the local population which is in dire need of supervision.

The Chinese Response

The Chinese government meanwhile refuses to even acknowledge the enormity of the matter. For them the matter ends with discussing the Dalia Lama and his rights to return. In principle, it neither recognizes the TGIE, nor any office-bearers in this government or its right to establish a dialogue on Tibet’s future. It views these incidents as politically motivated acts of separatism and any kind of human rights-violation allegation is scorned upon as in the case of the Human Rights Report issued by the US in May 2012.

The need for realistic solutions to the Tibetan issue however, is palpable amongst some sections within China who argue that an ethnic policy reform is unavoidable lest China wishes to see the state follow the USSR, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia model. The impending socio-political crises can be avoided only by allowing reasonable regional autonomy and bearing in mind local voices. Yet, whether China will be willing to reconsider its approach is highly doubtful.

Bhavna Singh

Research Officer, CRP, IPCS

email: [email protected]