Commanding Right And Forbidding Wrong: Rising Influence Of Muslim Mainstream Groups – Analysis

By ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute

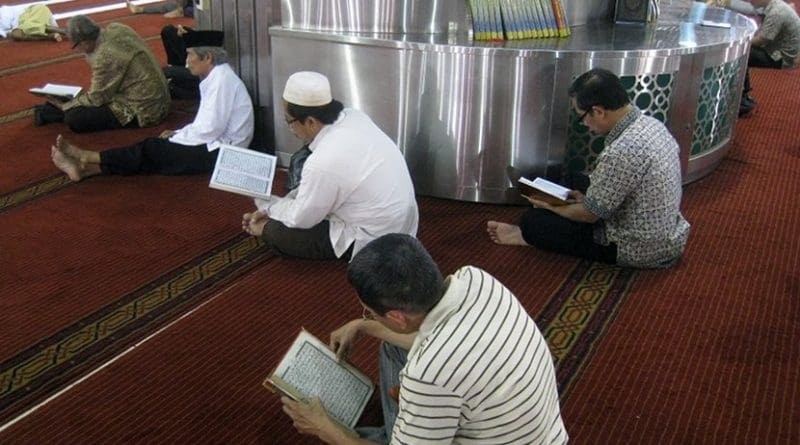

The banning of FPI (Front Pembela Islam) in December 2020 may have reduced the incidence of vigilante actions taken to enforce Islamic laws and norms in Indonesia. But this belies the fact that mainstream Muslim organisations such as Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) and Muhammadiyah, as well as the Indonesian Ulama Council (MUI), have increasingly stepped in to uphold more conservative Islamic strictures, albeit through less confrontational ways.

By Syafiq Hasyim*

INTRODUCTION

Prior to its official banning on 30 December 2020, Front Pembela Islam (FPI or Islamic Defender’s Front), the vigilante group led by radical cleric Habib Rieziq Shihab, had played a major role in moral policing and enforcing Islamic strictures in Indonesia. It had been at the forefront of efforts to enforce the Islamic practice of amar ma’ruf nahi munkar (commanding right and forbidding wrong) by conducting raids on nightspots and cracking down on deviant Islamic sects. Over the years, the group had also been increasingly politically active – supporting the Prabowo Subianto-Hatta Rajasa pairing in the 2014 presidential election and taking the lead in agitating against former Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (aka Ahok) over alleged blasphemy charges. President Jokowi eventually moved to ban the group when it became increasingly clear that FPI was also taking a lead role in mobilising Islamic opposition to Jokowi’s position as President.

Following the Jokowi administration’s banning of FPI, there was some hope that the more conservative and puritanical actors shaping Indonesian Islam would be neutralised. This Perspective argues that, in fact, the enforcement of conservative Islamic laws and norms has continued, championed by the mainstream Muslim organisations – NU, Muhammadiyah, and the MUI.

RECONNECTING WITH THE MUSLIM GRASSROOTS

Compared to the FPI, the mainstream Muslim organisations NU and Muhammadiyah had seemed relatively out of touch with the Islamic political agenda of the Muslim grassroots (umma). The FPI was popular at the grassroots level primarily because it had championed Islamist populist issues and was seen as defending the interests of marginalised Muslims. It was also able to connect with the grassroots at an emotional level as it had demonstrated its willingness to boldly confront the Jokowi government for alleged unjust acts committed against the Muslim community. For example, FPI had cast the arrest of Rizieq Shihab and other Muslim figures as examples of the Jokowi government’s criminalisation of and legal discrimination against ulama who expressed dissenting views about the government.[1] The FPI also tapped into longstanding Muslim grassroots unhappiness over the perceived injustices of Jokowi’s government in managing the economy. As Din Syamsuddin (former General Chairman of Muhammadiyah) had previously highlighted, many Muslims had felt unfairly treated and perceived the Jokowi government to be supporting the economic marginalisation of Muslims.[2] In this context, Thamrin Amal Tamagola, a sociologist from the University of Indonesia, observed that the FPI had been much more responsive in addressing the needs of poor urban communities, especially in Jakarta, compared to NU and Muhammadiyah which were perceived as elitist. The lack of grassroots presence by NU and Muhammadiyah amongst the urban poor had allowed FPI space to build up its following.[3] NU and Muhammadiyah are generally seen as championing their narrow causes. NU has prioritised issues such as education in pesantren, social welfare and upholding moderate Islam, while Muhammadiyah has appeared to be more focused on the economy, education and health issues of umma.

However, the banning of FPI in end December 2020 provided NU and Muhammadiyah with opportunities to reclaim their credibility and influence with the Muslim grassroots. Even prior to the banning of FPI, NU and Muhammadiyah were already aware of their weaknesses on this front and had begun making some changes to their dakwah in order to draw closer to the Muslim grassroots. Both NU and Muhammadiyah have given more attention to the phenomenon of the hijrah community among millennial groups through the use of social media platforms such as YouTube. Marsudi Syuhud of Nahdlatul Ulama has acknowledged that the conventional strategies of conducting face-to-face dakwah is no longer enough and stated that Nahdlatul Ulama’s preachers have started to use YouTube as the medium of their dakwah.[4] Some figures in Muhammadiyah have begun to make more appearances in social media.[5]

JOKOWI’S ACCOMMODATION OF THE MUSLIM ORGANISATIONS IN UPHOLDING CONSERVATIVE NORMS

Since the banning of FPI, NU and Muhammadiyah, together with MUI, have also taken positions that are very critical of some policies of the ruling regime. But unlike FPI which employed mass mobilisation to make their views heard, the mainstream Muslim organisations have instead opted to exercise pressure through less confrontational ways, often via the media and through institutional processes. And as the Jokowi government’s decisions on recent issues have shown, these mainstream Muslim organisations have been able to impose some conservative Islamic “supervision” over government policy. The following examples show that the Jokowi government’s accommodation of such pressure by MUI, Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah have sometimes come at the expense of pluralism and minority interests.

The first case concerns Indonesia’s Covid-19 vaccine rollout. Notwithstanding the fact that the government had made very early efforts to order China’s Sinovac and Sinopharm vaccines, and the UK’s AstraZeneca, the vaccines could not be released for public use without a fatwa from MUI being obtained first. Vice-President Ma’ruf Amin (who was General Chairman of MUI from 2015 to 2020) had said that the MUI could authorise the use of vaccines either by ruling that a vaccine was halal, or ruling that a non-halal vaccine could be used on the basis of darura, which allows for exceptions under emergency situations.[6] This appears to be an example of the MUI asserting sole authority of Indonesian Islam. The MUI eventually ruled that the Sinovac vaccine was halal. In contrast, the MUI ruled that the AstraZeneca vaccine was haram (due to its use of trypsin, a non-halal ingredient) but could nonetheless be used under emergency situations by invoking the principle of darura. This haram ruling on AstraZeneca’s vaccine status appears to have impacted its roll-out to some extent, with the Ministry of Health deciding not to use it in Jakarta. Interestingly, the AstraZeneca vaccine was approved for use in East Java where the provincial branch of Nahdlatul Ulama had declared AstraZeneca’s vaccine halal.[7] (East Java NU did so in opposition to MUI’s haram ruling and had justified it by using references to the Hanafi school of Islamic law, instead of the Shafii school of law which MUI and most other Muslim leaders in Southeast Asia subscribe to.) The fact that the AstraZeneca vaccine could be used in East Java indicates the importance of support from local religious leaders in implementing government policy. At the national level, it is also significant that President Jokowi had to respect the influence of MUI when he assured the Indonesian Muslim public that Sinovac would not be used without the issuance of halal fatwa from MUI. The visual image of Jokowi receiving his Sinovac shot under a huge banner with the tagline “Vaksin Halal dan Aman” (Vaccine: Halal and Safe) reflects how religion is prioritised in government policy.

The second case concerns Jokowi’s decision to cancel his Presidential Regulation No. 10/2021 on Investment which allowed for investment in the business of alcoholic drinks in four provinces—Bali, Nusa Tenggara Timur (NTT), Sulawesi Utara, and Papua.[8] Despite this policy being intended to apply only to the four non-Muslim majority provinces, the mainstream Muslim organisations stepped in to pressure the Jokowi government to cancel this regulation. MUI was at the forefront in rejecting this regulation on the basis that the consumption of alcohol is banned by Islam. As a consequence, investing alcoholic businesses should also be prohibited. Nahdlatul Ulama, which usually adopts moderate positions, was also irritated with this Presidential Regulation. Said Aqiel Siradj (General Chairman of Nahdlatul Ulama) proposed that the regulation be delayed because it was against the spirit of Islam. Muhammadiyah also shared the same opinion with MUI and Nahdlatul Ulama. After sustained pressure from these Muslim groups and Vice-President Ma’ruf Amin, Jokowi cancelled this regulation. Jokowi explained that the cancellation was based on his acceptance of the advice from ulama.[9] This reversal of policy by Jokowi disappointed many who saw it as an example of the government’s submission to religious authority, at the expense of pluralism. It also suggested that Jokowi, despite his efforts to crack down on hardliners like the FPI, has chosen to draw more closely to conservative ulama than before.

The Jokowi government also had to give in to pressure from mainstream Muslim organisations on at least two other policies. The first was over the exclusion of the word “religion” in the vision statement of the Ministry of Education and Culture’s Roadmap of Indonesia’s Education 2020-2035). Various key leaders from NU and Muhammadiyah had protested over its omission in the original draft. The crux of their unhappiness centred around concerns that the exclusion of the word “religion” could undermine the centrality of religion in education and daily life. Vice-President Ma’ruf Amin[10] also intervened to ask the Minister of Education and Culture to include the word “religion” in the draft vision statement to address criticism that the Indonesian education system could be perceived as a secular system.[11] Eventually, the Education Minister Nadiem Makarim acceded and included the word in the vision statement.[12]

The other policy which saw the Jokowi government reverse its position was over the proposal by the Ministry of Religious Affairs (under its former minister Fachrul Razi) to implement Islamic preacher certification to strengthen the moderation of Islam. This was an effort to deal with the rise of Islamic conservatism and radicalism in Islamic dakwah in Indonesia.[13] The Ministry of Religious Affairs had targeted the certification programme to involve around 8,200 Muslim preachers. But this programme was criticised by Muhammadiyah which questioned the need for it. Muhammadiyah stated that dakwah was a religious calling, and therefore the certification of this activity had no relevance.[14] MUI also opposed the move. Anwar Abbas from MUI stated that the dakwah certification programme would be used by the government of Indonesia as a political tool to control religious life in Indonesia. The MUI published a Maklumat (Announcement) stating that MUI as an ulama organisation rejected the initiative by the Ministry of Religious Affairs to implement the programme.[15] Due to the strong opposition from these organisations, the Ministry discontinued the programme.

EROSION OF MINORITY RIGHTS UNDER JOKOWI

Taken together, the cases cited above show that the mainstream Muslim organisations have been increasingly active and assertive in pressuring the government to uphold conservative Islamic laws and norms. The response of the Jokowi government shows an increasing tendency to accede to such pressure, a trend that has also extended to the continued marginalisation of minority groups. Ahmadiyyah followers have long hoped that Jokowi would prove to be a pluralist national leader that could protect their religious freedom.[16] Such expectations were strengthened when the Jokowi government weakened the role of radical and hardline Muslim groups such as FPI and other Islamist organisations. However, the marginalisation of groups like Ahmadiyyah has continued. For instance, attempts by the Ahmadiyyah community in Garut, West Java, to rebuild their mosque were blocked by the local government of Garut because it was considered to be against Joint Decree of Three Ministers No. 3/2008 on the restriction of Ahmadiyyah.[17] The Ahmadiyyah have also faced similar obstacles in other regions like in Kuningan, West Java. Apart from Ahmadiyyah, other local indigenous groups have also faced continued curbs on their religious freedom from the mainstream Muslim organisations. For instance, the followers of Sunda Wiwitan (an indigenous religion in Kuningan, West Java) that has long struggled for their religious rights such as building their place of worship, are still facing discrimination. They also face difficulty accessing basic civil rights such as getting their identity card (KTP) to include mention of their belief or religion. The absence of mainstream Muslim organisations’ response to all these cases reflects their regressive position and their lack of willingness to empower the marginalised minority groups.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The banning of radical groups such as FPI has not resulted in a reduction of conservative enforcement of Islamic laws and norms regulating Muslim life in Indonesia. The established mainstream organisations like NU, Muhammadiyah and MUI have stepped in to fill the void. What makes them different from FPI is their approach in enforcing the supervision of Islam in daily life. FPI had used a hard and confrontational approach, while the mainstream Muslim organisations have preferred using softer tactics. Based on the various cases discussed, it would seem that these organisations have been more effective in exerting their influence and advancing their agenda. This is probably because they have people in key positions in the Jokowi government and also a strong network among policy makers and state administrators. They have also been greatly helped by having Ma’ruf Amin as Vice-President. The response of the Jokowi government to pressure from them has been accommodative, indicating Jokowi’s political pragmatism in dealing with issues of Islam.

*About the author: Syafiq Hasyim is Visiting Fellow at the Indonesia Studies Programme, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. He is also Lecturer and Director of Library and Culture at the Indonesian International Islamic University (UIII), a newly established international graduate university, and Adjunct Lecturer at the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta.

Source: This article was published by Indonesia Studies Programme, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute.

ENDNOTES

[1] https://kumparan.com/kumparannews/fpi-soal-praperadilan-habib-rizieq-berantas-kriminalisasi-ulama-1umj5ispaVW, viewed on 24 May 2021.

[2] https://kbr.id/nasional/01-2017/sebut_umat_islam_dipojokkan__din_syamsuddin_kritik_negara__ahok_dan_pers/88226.html, viewed on 24 May 2021.

[3] Thamrin Amal Tamagola is a sociologist of University of Indonesia. He has highlighted the lack of attention from Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama towards poor urban communities, see https://www.cnnindonesia.com/nasional/20210122190358-20-597363/tamrin-jelaskan-klaim-pandji-soal-nu-muhammadiyah-elitis, viewed on 24 May 2021.

[4] https://www.cnnindonesia.com/nasional/20190516190532-20-395594/anak-muda-hijrah-di-mata-nu-dan-muhammadiyah, viewed on 24 May 2021.

[5] https://www.wartaekonomi.co.id/read182663/jokowi-sebut-muhammadiyah-sukses-berdakwah-lewat-media-sosial.html, 24 May 2021.

[6] https://www.merdeka.com/peristiwa/wapres-maruf-amin-sebut-izin-bpom-dan-fatwa-mui-harus-ada-sebelum-vaksinasi-covid-19.html, viewed on 24 May 2021.

[7] https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2021/03/25/after-mui-fatwa-astrazeneca-vaccine-sent-to-east-java.html, viewed on 8 June 2021

[8] https://www.cnbcindonesia.com/news/20210302182124-4-227338/siapa-yang-awalnya-desak-jokowi-restui-investasi-miras, viewed on 27 April 2021.

[9] https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2021/03/02/13105141/jokowi-putuskan-cabut-aturan-soal-investasi-miras-dalam-perpres-10-2021 , viewed on 30 April 2021.

[11] https://www.republika.id/posts/14856/wapres-minta-ada-agama-di-peta-jalan-pendidikan

[12] https://fulcrum.sg/pancasila-and-the-missing-word, viewed on 25 May 2021.

[13] https://www.liputan6.com/news/read/4351073/program-penceramah-bersertifikat-kementerian-agama-sasar-8200-dai, viewed on 24 May 2021.

[14] https://www.cnnindonesia.com/nasional/20200908074734-20-543830/pp-muhammadiyah-penceramah-dari-ormas-tak-usah-sertifikasi, viewed on 24 May 2021.

[15] https://news.detik.com/berita/d-5164473/mui-tolak-sertifikasi-dai-berpotensi-jadi-alat-kontrol-kehidupan-keagamaan, viewed on 24 2021.

[16] https://tirto.id/saat-pemerintahan-jokowi-membiarkan-pemberangusan-ahmadiyah-cq7p, viewed on 25 May 2021.

[17] https://www.cnnindonesia.com/nasional/20210506195757-20-639703/bupati-setop-pembangunan-masjid-ahmadiyah-di-garut, viewed on 25 May 2021.