Pakistan’s Civil-Military Relations – Analysis

Pakistan’s demographic makeup, with ethnic groups spread across borders, contributes to security and governance challenges.

By Riaz Hassan*

Of Pakistan’s many problems nothing is perhaps as enduring or as debilitating as the conflictual relationship between its civilian leadership and the military. Unlike in most democratic countries, Pakistan’s elected civilian government rarely commands the gun. Scholarly debates and analyses have identified multiple reasons including weak political institutions and parties, incompetent political leadership, the entrenched power of the civil-military bureaucracy, and threats to Pakistan’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Other contingent factors arising from the country’s demography and geography contribute to Pakistan’s difficulties, but are rarely given attention for shaping the civil-military relations, governance and security challenges that the Pakistani state has faced from the onset. The imperatives of geography, demography and security play a critical but varying role in shaping relations between civilian and military leaders in other countries as well.

Weak institutions are often attributed to the lack of well-established political parties headed by competent leaders. This, in turn, has failed to develop the basis for a robust and effective political and constitutional system, seriously impeding the government’s ability to respond to a myriad of internal and external challenges it faces related to national cohesion and integration, ethnic tensions, sectarianism, regional inequalities and international relations. In this space the bureaucratic military elite has become steadily more assertive, increasing its power at the expense of the country’s political elite.

The military is Pakistan’s most trusted, disciplined and cohesive Institution. Its composition closely corresponds to Pakistan’s demography. At 57 percent Punjabis make the majority followed by Sindhis, 17 percent; Pasthun, 15 percent; Kashmiris, 9 percent; and Balochis, 3 percent.

Between 1980 and 2000 four democratically elected governments were dismissed by the country’s presidents on charges of corruption, inefficiency and an inability to meet security challenges. This resulted in the strengthening of the civil-military bureaucracy. Indeed, civilian bureaucrats or military generals have governed Pakistan for almost 45 of its 70 years. These factors have undoubtedly played a role in shaping civil-military relations in Pakistan.

Before the July national elections Pakistani media were replete with stories about the army’s role in the removal of Nawaz Sharif as prime minster and the support of his archrival and now prime minister – Imran Khan, a Pashtun with strong family roots in the Punjab. The army of course vehemently denies these allegations. But perceptions matter.

The Montevideo Convention on Rights and Duties of the States, a treaty signed in 1933, defines a state as possessing a permanent population, a defined territory and a government capable of maintaining effective control over its corresponding territory and conducting international relations with other states.

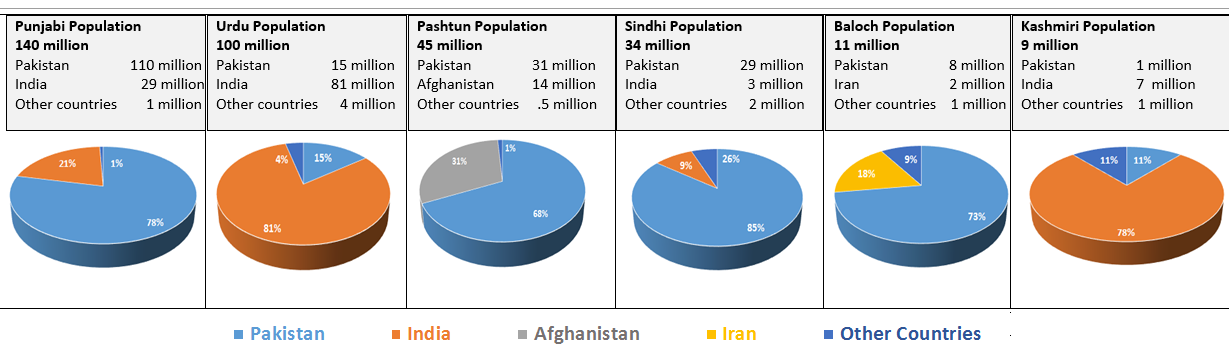

The most striking aspect of Pakistan’s demography is that it is made up of six “nations,” each divided between two or, in the case of Balochis, three countries. All are predominantly Islamic, but also endowed with their own distinct, historically grounded cultural identities. The geographical contour of Pakistan and its demographic heterogeneity has had profound implications for Pakistani’s territorial integrity, social cohesion, political stability, security and international relations – and the table shows the geographical contour of the state of Pakistan and the ethnic heterogeneity of its population.

Kashmir has been a source of intermittent military skirmishes and conflicts with India since 1947, and these have been the source of Pakistan’s deteriorating relations with its neighbor. The area remains a major political and security challenge for Pakistan. Baluchistan, Pakistan’s largest province, resource-rich and sparsely populated, straddles Pakistan and Iran. Around 75 percent of the Balochi population resides in Pakistan, while the rest live in Iran and Afghanistan. It too has been a site of decades of ethnic conflict with the Pakistani government over regional inequalities and the exploitation of its mineral and gas resources, which failed to deliver real economic and social benefits to Balochis. The Pakistani army has carried out numerous operations in the province under the rubric of counterterrorism, only serving to heighten ethnic tensions. The province also continues to be a site of incidents carried by Balochi nationalists.

But perhaps the most serious political challenge facing Pakistan concerns the conflict in Afghanistan, which, like the other disputes, also shares a significant demographic dimension. The Pashtun nation consists of approximately 45 million people. Pakistan is home to 31 million Pashtuns, about 70 percent of the population, with Afghanistan home to another 14 million or about 30 percent. The Pashtuns are overwhelmingly a tribal society, their identity grounded in the historical memory of a common lineage, Islam and the over-arching universal tribal code of Pashtunwali. These features constitute the social and cultural “glue” of solidarity among the Pashtuns of both countries.

While Pashtunwali rules are not a detailed legal code, they provide an all-encompassing framework for behavior and managing conflicts in Pashtun society. According to the code, when one’s honor is harmed, a person has a duty to respond by seeking revenge greater than the original slight. This dynamic offers deeper insight into the Taliban insurgency. Most Pashtuns are deeply conservative and strongly attached to their tribal values. Moreover, the majority of Taliban fighters are Pashtuns in culture and character, with a deep sense of shared identity. They are outraged by those who usurp their autonomy and denigrate their culture. The core logic of the Taliban insurgency is that they fight for the defense of their country, honor and religion, to avenge the deaths of relatives killed by Western forces and allies alike.

The proxy wars between the United States and the Soviet Union in Afghanistan following occupation in 1979 by Russia and after 2001 by the United States, its allies and the Taliban have made Pakistan an intersection of several global fault-lines. This, too, has had serious consequences for its economy, political stability, sovereignty and territorial integrity. Under these conditions, and in the face of the external threat of aggression and war, the Pakistani military has been obliged to perform its constitutional duty to ensure national security and unity, and to assist the government in its humanitarian mission. The conditions in Afghanistan, over which Pakistan has no real control, have compounded the problems of chronic political instability and difficult civil-military relations.

In conclusion, weak political institutions and parties and incompetent leadership as well as the country’s geography and demography contribute to governmental failings and complex civil-military relations in Pakistan. This reality is reflected in public opinion polls that show a low level of trust in the government at 36 percent along with parliament, 27 percent; political parties, 30 percent; and politicians, 27 percent. In this context the most trusted institution in the country is Pakistan’s army, which is trusted by 82 percent of the population. But despite the lack of confidence in political intuitions and high trust in the army, most Pakistanis do trust democracy. According to a December 2017 Gallup Poll, 81 percent of Pakistanis prefer democracy, while only 19 percent would rather have a military dictatorship. Recent electoral developments suggest that Pakistan may be heading towards sustainable democracy.

*Riaz Hassan is a visiting research professor at the Institute of South Asian Studies National University of Singapore and senior honorary fellow at the Asian Institute, University of Melbourne. He is also director of the International Centre for Muslim and Non-Muslim Understanding at the University of South Australia and emeritus professor of Sociology at Flinders University.