China’s Modus Operandi For Assertion In South And East China Seas: Relevance For India – Analysis

By SAAG

By D. S. Rajan

To suit to its grand strategy of achieving modernization of the country by middle of the century and convey to the outside word that its rise will be peaceful , the People’s Republic of China (PRC ) is implementing a foreign policy model which, as it visualizes, would create a ‘win-win ‘ situation in international relations. However, with the introduction of the ‘core interests’ principle in external relations in the post-2009 period , which gives equal priority to the need for protection of the country’s sovereignty, disallowing any compromise and even suggesting the use of force for the same, an assertive character is getting more and more pronounced in the model, somewhat diluting its original benevolent goal. As a result, the countries having land and sea territorial disputes with China are being subjected to a high degree of uneasiness.

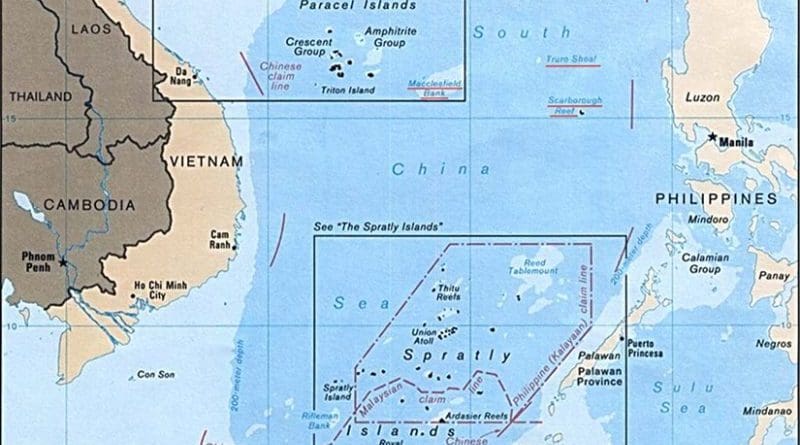

The disputes have led to sudden flare ups now, mainly due to the fresh competition between China and other powers in exploring off-shore oil and gas resources as well as the repercussions from the announced US ‘Asia-Pivot’ policy aimed at bolstering its regional military profile. They involve four island chains, all with resource-rich surroundings. Three of them, contested by China and several ASEAN nations, are in South China Sea – Paracel (now under China’s control), Spratlys ( reefs and shoals with China) and Macclesfield Bank ( China-the Philippines stand off point), called respectively by Beijing as Xisha, Nansha and Zhongsha. The fourth, claimed by China and Japan, is in the East China Sea – the Senkakus islands as Japan calls them ( now under Tokyo’s control), Diaoyu as the PRC calls it.

A study of patterns of China’s assertiveness with regard to the above mentioned disputes , reveals that in its application, there are five dimensions – administrative , military, economic, diplomatic and policy support . The Chinese official media call them as “combination punches” (People’s Daily, 13 August 2012). What follows is a detailed account of the patterns , in which an attempt has been made to examine the features of the PRC’s modus operandi that is being adopted for the purpose of asserting its sea territorial claims in East Asia and correlate them to questions concerning India – whether or not Beijing can use the same or some aspects of that modus operandi while dealing with New Delhi and if so, how India should react . The exercise undertaken is on the acceptable premise that at a time when it is finding necessary to resort to an aggressive assertion in the case of sea boundaries in East Asia, China in its overall geo-political interests, is inclined towards adopting a low-key approach towards land border issues like the one with India. However, the study tries to make some projections , looking at the situation in a long term , considering prudent not to rule out the possibility of China vigorously asserting its border claims against India at an opportune time, given its likely consistent position of ‘no compromise’ on all ‘sovereignty’ related issues.

Taking the administrative dimension first, what is striking is that China’s assertiveness is assuming certain new forms. The PRC’s major thrust has so far been on gathering historical evidences to strengthen its territorial claims. It is now is using an additional mean – taking administrative measures intended to gain jurisdiction over the claimed regions. Notable are legal steps now being taken by China to “ select and protect base points” of islands under dispute under the ‘ China Islands Protection Law’, passed by the China State Oceanic Administration ( Xinhua, 13 September 2012). Sansha city in Yongxiung island of Hainan province is one such base point selected. The administrative status of Sansha city, so far ranking as a County, was upgraded to the level of a Prefecture on 24 July 2012; the responsibilities assigned by the PRC Ministry of Civil Affairs to the status-updated Sansha city are “ further strengthening of China’s administration and development” of the three South China sea island groups – Xisha, Nansha and Zhongsha. In such situation, the dispatch by authorities of Chinese trawlers and escort vessels to the disputed islands in South China Sea in June-July 2012 appears to have been a step to justify that action on legal grounds. Also not to be missed is the establishment of a military garrison in Sansha city on 26 July 2012, with the stated charter of ‘military mobilisation ‘; to prevent any misgiving abroad naturally arising out of this measure, Beijing is giving adequate media publicity to its defence that the Sansha city garrison is not for ‘combat’ purposes, which are being handled by the Xisha (Paracels) garrison (China Daily, 27 July 2012)

The Sansha city example, when subjected to a closer scrutiny, may have relevance to studies on future trends in China’s land border dispute with India. Chinese official literature ( http// eng.tibet.cn/2010/home/news/201204/t2012 dated 15 A pril 2012) have described Tawang in India’s Arunachal Pradesh as “the‘ birth place of the Sixth Dalai Lama belonging to Cuona county of Shannan prefecture in the Tibet Autonomous Region”. Also, in some unofficial media coverages in the PRC , the Chinese occupied Aksai Chin is being termed as an area under “Hotan County of Hotan Prefecture “in Western China. In such context, following questions may be of interest to India – whether China can assert its claims over Tawang and Aksai Chin through issuing Sansha-type notifications formally bringing the two areas under the administrative controls of Shannan and Hotan Prefectures respectively ? Or, whether such notifications have already been issued by China? Will China chose to provoke India by taking such measures? Does India have adequate mechanisms to monitor such notifications if issued? Undoubtedly, answers to them may equip India with some useful indicators to Chinese thinking on the boundary problem.

China’s assertiveness with respect to East China Sea island issue is manifesting in a form, not seen before- domestic channels of the PRC’s National TV have begun to broadcast from end August 2012 weather reports for Senkakus, as a firm message to the Japanese side that Senkakus is China’s internal part. How about the possibility of Tibet domestic TV broadcasting weather reports on ‘Southern Tibet’, i.e India’s Arunachal Pradesh? Or, is this already being done? These points should not be missed by India.

China’s use of maps to assert its border claims or ‘cartographic aggression’ as some call, is not new. But what was the need for the PRC’s recent setting up of a Steering Sub-Committee for guiding, coordinating and supervising preparation of country’s maps ? What is the role of PRC Foreign Ministry’s Department of Boundary and Ocean Affairs established not long ago? What is the purpose behind the recent formation of a Strategic Planning Agency under the General Staff Department of the People’s Liberation Army? Are the opinions of such rather new administrative units contributing in any way to China’s present territorial assertion abroad? Again, these aspects merit India’s attention.

China has opened Xisha islands (Paracel) under its control for tourism – marking another indirect way of asserting territorial sovereignty. Will China object to India’s launching of tourism projects in Arunachal? New Delhi should be alive to any indication to this effect, as Beijing even contested Indian PM’s official visit to Arunachal.

The PRC is apparently encouraging its nationals to go to Senkakus, in attempt to signal its intention to assert its territorial rights over that island. ‘Grass roots’ activists from Hongkong have also gone to Senkakus. Tokyo, a claimant to Senkakus, has arrested 14 Chinese nationals on charges of intrusions. These developments may be relevant to India. There have been Chinese troop intrusions into Indian border. It is however not clear whether Chinese civilians were found entering Indian boundaries. In any case, New Delhi may have to be careful over China using intrusions as a mean to assert its claims.

Concerning military dimension of China’s territorial assertiveness, what can be seen without difficulty is Beijing’s tendency of applying strategic pressure on contesting nations under a belief that the same may indirectly strengthen its negotiating position on sea and land border disputes with the latter. To illustrate, there were island landing drills by Chinese troops around Huangyan island (Scalborough Shoal, under dispute with the Philippines) . Combat-ready Chinese patrols were in operation in the disputed areas in South China Sea in June 2012. A Chinese Naval exercise was held in the Yellow sea. China’s Marine Corps has conducted amphibious combat training operations. A sixth Type 052C Luyang-class destroyer was added so as to augment naval capabilities for enforcing claims over South and East China Seas. New civilian ships capable of carrying out maritime transportation of military troops are being launched by the Chinese Navy.

Through increasing its military profile across the Indian border, Beijing seems to be intent on applying strategic pressure on New Delhi also, with a view to gaining a position of strength during border negotiations with India. Military infrastructure building in Tibet is in full swing, about which details are already known. Notable are the reported deployment of missiles and the trend to conduct integrated ground-air operations in Tibet. Such operations with live ammunition were organised ‘over Himalayas’ by a mountain infantry brigade under Tibet Military Command on 13 August 2012. Use of Air Force in Tibet has an external dimension; Beijing does not need Air Force to suppress civilian unrest in Tibet; definitely, it has an external target – India. New Delhi is reacting to this situation by taking steps to develop its own border infrastructure. Notwithstanding such signs of India-China strategic competition, their common border is now quiet and as a result of resumption of high-level military exchanges between the two sides, the military trust-deficit between them seems to have subsided. However, it would be in India’s interests to develop a long term view of Chinese strategic pressures.

Looking at the economic dimension, China’s assertiveness can be seen in relation to the competition that has erupted between contesting powers in South and East China Seas over the rights to exploit the offshore oil and gas deposits. The Chinese decision to open nine offshore areas in South China Sea for commercial joint exploration and similar actions by Vietnam, are exacerbating the crisis in the region. This factor needs to be given a careful consideration by India which has signed an agreement with Vietnam on oil exploration in areas being contested by China and Vietnam in South China Sea. Overall, New Delhi’s challenge will be on how to strengthen its position globally on exploration of off-shore energy conducive to its development, without getting sucked into any regional territorial dispute.

China is taking diplomatic initiatives to improve relations with ASEAN nations and Japan with the objective of reducing the levels of present sea territory tensions in the region. “Shelving the disputes and working for common development”, is China’s formula being applied in this regard. Beijing’s charm offensive, is however, not leading to desired results. The diplomatic visits of Chinese Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi to Indonesia, Brunei and Malaysia in August 2012 provided an opportunity for the PRC to explain its position on the maritime issues in East Asia – they need to be solved bilaterally between the concerned nations. The US, also an Asia-Pacific player, on the other hand, wants a multilateral solution. The ASEAN opinion on code of conduct in South China Sea is also divided. Under the circumstances, the Chinese diplomacy seems to be operating with a limited aim- reducing tensions, leaving solutions to a later date. China’s diplomatic initiatives in the case of India also, need to be seen from this angle. The Indian External Affairs Minister has paid a visit to China in February 2012, followed by that the PRC Defence Minister to India in September that year. The created good atmosphere notwithstanding, it looks certain that a long way awaits the two nations in solving strategic issues dividing them, like the border problem. A firm indicator one sees in the current Chinese flexing of military muscles on South and East China Seas is that Beijing’s basic ‘uncompromising’ attitude towards all sovereignty-related issues, including the India-China boundary question, will remain forever.

The last dimension of China’s assertiveness in South and East China seas lies in policy support. It cannot be denied that Beijing’s territorial assertiveness is a result of policy formulations made at high levels. Statements being made at leadership levels reflect the agreed policies. First example relates to expressions of China’s unambiguous commitment to the need for not giving any ‘concession’ on issues concerning its sovereignty and territorial integrity. Premier Wen Jiabao has himself declared it (10 September 2012). China’s Defence Minister Liang Guanglie has stated in an interview (December 2010) that “in the coming five years, China’s military will push forward preparations in every strategic direction”. The editorials in the PRC’s official press including in the PLA Daily, are also making repeated stress on the need for the country’s diplomacy to maintain ‘uncompromising’ territorial positions. China’s last Defence White Paper has found ‘local conflicts’ possible. It may be wrong to take such statements as only rhetoric; on the contrary, they seem to reflect a leadership consensus on directions of Beijing’s foreign policy. Turning to India, suffice to say that it would be essential for it to correctly understand the practical meaning of China’s present ‘core interests’ based foreign policy- China may not be not willing to give up its option to use force at an opportune time, if it considers necessary, to settle territorial issues, including the one with India.

(The writer, D. S. Rajan, is Director, Chennai Centre for China Studies, Chennai, India. Email: [email protected])