The Kissinger Story – OpEd

By Uri Avnery

I am writing this (may God forgive me) on Yom Kippur.

Exactly 43 years ago, at this exact moment, the sirens sounded.

We were sitting in the living room, looking out on one of Tel Aviv’s main streets. The city was completely silent. No cars. No traffic of any kind. A few children were riding about on their bicycles, which is allowed on Yom Kippur, Judaism’s holiest day. Just like now.

Rachel, my wife, I, and our guest, Professor Hans Kreitler, were in deep conversation. The professor, a renowned psychologist, was living nearby, so he could come on foot.

And then the silence was pierced by a siren. For a moment we thought that it was a mistake, but then it was joined by another and another. We went to the window and saw a commotion. The street, that had been totally empty a few minutes before, began to fill up with vehicles, military and civilian.

And then the radio, which had been silent for Yom Kippur, came on. War had broken out.

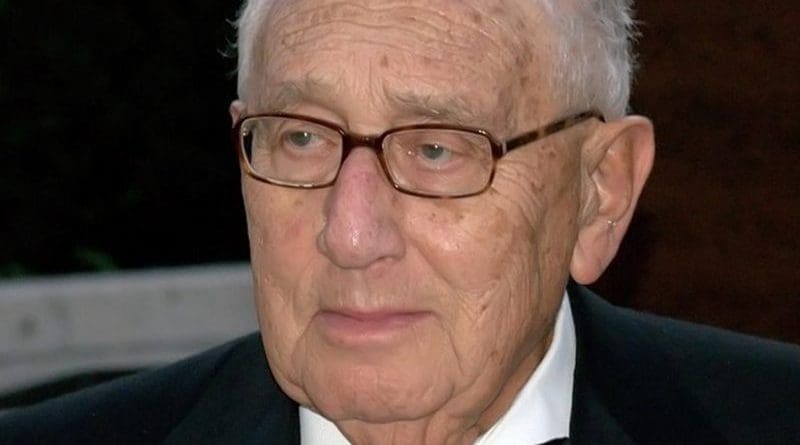

A few days ago I was asked if I was prepared to talk on TV about the role of Henry Kissinger in this war. I agreed, but at the last moment the program was canceled, because the station had to devote the time to showing Jews asking God for forgiveness at the Western Wall (alias the Wailing Wall). In these Netanyahu times, God, of course, comes first.

So, instead of talking on TV, I shall write down my thoughts on the subject here.

Henry Kissinger has always intrigued me. Once my friend Yael, the daughter of Moshe Dayan, took me – in the great man’s absence, of course, since he was my enemy – to his large collection of unread books and asked me to choose a book as a present. I chose a book of Kissinger’s, and was much impressed by it.

Like Shimon Peres and I, Kissinger was born in 1923. He was a few months older than the other two of us. His family left Nazi Germany five years later than I and went to the US, via England. We both had to start working very early, but he went on with his studies and became a professor, while poor me never finished elementary school.

I was impressed by the wisdom of his books. He approached history without sentiment and dwelled especially on the Congress of Vienna, after Napoleon’s downfall, in which a group of wise statesmen laid the groundwork for a stable, absolutist Europe. Kissinger stressed the importance of their decision to invite the representative of vanquished France (Talleyrand). They realized that France must be part of the new system. To ensure peace, they believed, no one should be left out of the new system.

Unfortunately, Kissinger in power disregarded this wisdom of Kissinger the Professor. He left the Palestinians out.

***

The subject I was to speak about on TV was a question that has intrigued and troubled Israeli historians since that fateful Yom Kippur: Did Kissinger know about the impending Egyptian-Syrian attack? Did he deliberately abstain from warning Israel, because of his own nefarious designs?

After the war, Israel was rent asunder by one question: why had our government, led by Prime Minister Golda Meir and Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, disregarded all the signs of the coming attack? Why had they not called up the army reserves in time? Why had they not sent the tanks to our strongholds along the Suez Canal?

When the Egyptians attacked, the line was thinly held by second-class troops. Most soldiers were sent home for the high religious holiday. The line was easily overrun.

Israeli intelligence knew of course of the massive movement of Egyptian units towards the canal. They disregarded it as an empty maneuver to frighten Israel.

To understand this, one has to remember that after the incredible victory of the Israeli army only six years earlier, when it smashed all the neighboring armies in six days, our army had abysmal contempt for the Egyptian armed forces. The idea that they could dare to carry out such a momentous operation seemed ridiculous.

Add to this the general contempt for Anwar al-Sadat, the man who had inherited power from the legendary Gamal Abd-al-Nasser a few years earlier. Among the group of “Free Officers” who, led by Nasser, had carried out the bloodless 1952 revolution in Egypt, Sadat was considered the least intelligent, and therefore appointed by consent as Nasser’s deputy.

In Egypt, a country of innumerable jokes, there was joke about that, too. Sadat had a conspicuous brown spot on his forehead. According to the joke, whenever a subject came up in a Free Officers’ Council meeting, and everyone expressed his view, Sadat would stand up last and start to speak. Nasser would put his finger on his forehead, press it gently and say: “Sit down, Anwar, sit down.”

In the course of the six years between the wars, Sadat several times conveyed to Golda that he was ready for peace negotiations, based on Israel’s withdrawal from the occupied Sinai Peninsula. Golda contemptuously refused. (In fact, Nasser himself had decided on such a move just before he died. I played a small role in conveying this information to our government.)

Back to 1973: almost at the last moment Israel was warned by a well-placed spy, no less than Nasser’s son-in-law. The message gave the exact date of the impending attack, but the wrong hour: instead of noon, it predicted the early evening. A difference of several fateful hours. In Israel it was later debated whether the man was a double agent and had give the false hour on purpose. It was too late to ask him – he had died in mysterious circumstances.

When Golda informed Kissinger about the impending Egyptian move, he warned her not to carry out a preemptive strike, which would put Israel in the wrong. Golda, trusting Kissinger, obeyed, contrary to the views of the Israel Chief of Staff, David Elazar, nicknamed Dado.

Kissinger also delayed informing his own boss, President Nixon, by two hours.

***

So what was Kissinger’s game?

For him, the main American aim was to drive the Soviets out of the Arab world, leaving the US as the sole power in the region.

In his world of “realpolitik”, this was the only objective that mattered. Everybody else, including us poor Israelis, were just pawns on the giant chessboard.

A major but controlled war was for him the practical way to make everybody in the region dependent on the US.

When the Egyptian and Syrian attacks initially succeeded, Israel was in panic. Dayan, who in this crisis showed himself to be the nincompoop he really was, bewailed the “destruction of the Third Temple” (adding our state to the two Jewish temples of antiquity which were destroyed by the Assyrians and the Romans respectively.) The army command, under Dado, kept its cool and planned its counter-moves with admirable precision.

But munitions were running out quickly and Golda turned in despair to Kissinger. He set in motion an “air bridge” of supplies, giving Israel just enough to defend itself. Not more.

The Soviet Union was helpless to interfere. Kissinger was king of the situation.

***

With remarkable resilience (and the weapons delivered by Kissinger) the Israeli army turned the tables, pushing the Syrians back well beyond their starting point and nearing Damascus. On the Southern front, Israeli units crossed the Suez Canal and could have started an offensive towards Cairo.

It was a rather confused picture: an Egyptian army was still east of the Canal, practically encircled but still able to defend itself, while the Israeli army was behind its back, west of the canal, also in a dangerous position, liable to be cut off from its homeland. Altogether, a classic “fight with reversed fronts”.

If the war had run its course, the Israeli army would have reached the gates of Damascus and Cairo, and the Egyptian and Syrian armies would have begged for a cease-fire on Israeli terms.

That’s where Kissinger came in.

The Israeli advance was stopped on Kissinger’s orders 101 km from Cairo. There a tent was set up and permanent cease-fire negotiations started.

Egypt was represented by a senior officer, Abd-al-Rani Gamassi, who soon captured the sympathy of the Israeli journalists. The Israeli representative was Aharon Yariv, former chief of army intelligence, a member of the government and a general of the reserves.

Yariv was soon recalled to his seat in the cabinet. He was replaced by a very popular regular army general, Israel Tal, nicknamed Talik, who happened to be a friend of mine.

Talik was devoted to peace, and I often urged him to leave the army and become the leader of the Israeli peace camp. He refused, because his overriding passion was to create the Merkava, an original Israeli tank that would give its crew maximum security.

Immediately after the fighting I met Talik regularly for lunch in a well-known restaurant. Passersby may have wondered about these two – the famous tank general and the journalist universally hated by the entire establishment – conversing together.

Talik told me – in confidence, of course – about what had happened: one day Gamassy had taken him aside and told him that he had received new instructions – instead of talking about a cease-fire, he could negotiate an Israel-Egyptian peace.

Immensely excited, Talik flew to Tel-Aviv and disclosed the news to Golda Meir. But Golda was cool. She told Talik to abstain from any talk about peace. When she saw his utter consternation, she explained that she had promised Kissinger that any talks about peace must be held under American auspices.

And so it happened: a cease-fire agreement was signed and a peace conference was called in Geneva, officially under joint US and Soviet auspices.

I went to Geneva to see what would happen. Kissinger was there to dictate terms, but Andrei Gromyko, his Soviet counterpart, was a tough customer. After a few speeches, the conference adjourned without results. (For me it was an important event, because there I met a British journalist, Edward Mortimer, who arranged for me to meet the PLO representative in London, Said Hamami. Thus the first Israeli-PLO meeting came about. But that is another story.)

The Yom Kippur war cost many thousands of lives, Israeli, Egyptian and Syrian. Kissinger achieved his goal. The Soviets lost the Arab world to the United States.

Until Vladimir Putin came along.