Can Life At Sea Teach Us To Live In A More Meaningful Way?

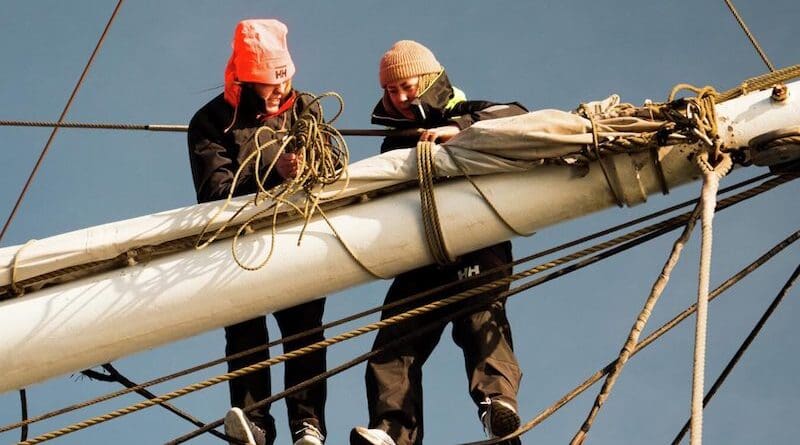

‘Eric’ loves climbing the mast. In the summer of 2022, he is on his second voyage with the tall ship Christian Radich.

He will spend a whole month at sea and has long since become famous among the 40 other young people on board for his climbing skills and nerves of steel.

If it were up to him, he would sail for months, says ‘Eric’. This is despite hard work, night shifts, sea sickness and almost no alone time. The time he has spent on board the tall ship has turned his life around.

“Before the first voyage, I was a real loner: I just sat in my room. I couldn’t talk to other people and I didn’t even want to meet them. But after two weeks of sailing, I finally plucked up enough courage and started talking to people. It was as if something just fell into place,” says ‘Eric’, with a snap of his fingers.

Therapy in the blue

‘Eric’ is not the young seaman’s real name. He has been anonymised in connection with a research interview.

The aim is to investigate the effect of the programme he has taken part in, Windjammer, a project for children and young people who are at risk of exclusion from working life and education.

The idea of spending time at sea to grow as a person is by no means new. In the 1940s, the Outward Bound movement began offering four weeks of sailing to young Americans as a way to build character.

Later, many of the same principles have been continued in forest and mountain camps.

“It is from here that what we know today as outdoor therapy has its origins,” says Gunvor Marie Dyrdal.

She is a psychologist and associate professor at the Department of Health Sciences at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) in Gjøvik. Together with her colleague Helga Synnevåg Løvoll, she has led the research collaboration with Windjammer.

Although a lot of research has already been done on outdoor therapy, Dyrdal believes that there are still important pieces of the puzzle missing in our understanding of the effects of these types of programmes.

One thing is that little research has been conducted into outdoor therapy specifically in the blue element, i.e. at sea. The role that meaningfulness plays is also poorly understood, she explains.

Adding meaning to life

“Meaningfulness or purpose is an important ingredient in the lives of all people, but it is especially important for young people. Adolescence is a vulnerable period for many people, characterised by difficult questions related to identity, values, education and independence.

A lot of research shows that having a sense of purpose and meaning is especially important during this period. It is therefore natural to believe that meaningfulness also plays a crucial role for young people at risk,” says Dyrdal.

She feels it is important to make a distinction between the big, rather overwhelming questions about the meaning of life and the more tangible role meaningfulness plays in our lives.

The latter is the thing she is most interested in. She believes this perspective is less passive and encourages a sense of being more in control of your own life.

“When we regard meaning as something we create, rather than something abstract that is somewhere out there and needs to be discovered, we suddenly have a little more control over our lives.

It also encourages an important curiosity about oneself: Who am I? What am I good at? What is important in my life? Many people have never had the opportunity to stop and ask these questions. Many just do what their parents do or what they think society expects them to do,” says the psychologist.

Her research suggests that the young people who get to go on a voyage with Christian Radich get the opportunity to think about such things.

In the same boat – for better or worse

The young people taking part in the Windjammer voyage are often recruited through the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration (NAV) or the Follow-up Service. In addition, some of the young participants have signed up themselves via the project’s website.

When they are not out working on one of the two daily 4-hour shifts, they sleep, eat or stay in the confined living quarters under the main deck.

“Good collaboration is crucial not only for living on board a tall ship, but also for operating it,” says Dyrdal.

Even something as basic as hoisting the sails requires many people to do the job.

“You have to pull together at the same time, and everyone who does the task knows that what they are doing at that moment is important for the whole crew, for the whole ship. As a result, the significance of your work tasks becomes very visible.”

“It is the same thing regarding the expectations of those around you. Unlike in many other situations in life, there is nowhere to hide or escape to when you are at sea. You are simply in the same boat – for better or worse,” says the researcher.

So, it probably wasn’t that strange that the social aspect on board the ship emerged as one of the four most important interview topics, and was absolutely crucial in terms of how much the participants got out of the voyage.

Accepting oneself, learning practical seamanship and being open to what the experience has to offer were other important aspects.

Post-sailing depression

In addition to interviews, researchers have collected psychological and demographic data from the participants using digital surveys both before and after the voyage:

By comparing these with the results of the national survey, the researchers found that the Windjammer participants experienced life before the voyage as less meaningful than most young people.

What is perhaps more surprising is that after their four weeks at sea, the young participants’ sense of meaningfulness and purpose was lower than it had been before the voyage.

Does this mean that the voyage only made things worse?

“The interviews suggest that the voyage had a positive effect on the participants’ perception of themselves and their lives. Among other things, they talk about a sense of being more in control and having a clearer purpose in life,” says the NTNU researcher.

However, she thinks that the fact that the follow-up data suggest a lower perceived meaningfulness in life among participants after the voyage may be because they have now had a taste of a different kind of life.

“Many of the participants really feel the contrast when they return home. Maybe they have seen new possibilities and discovered new aspects of themselves during the voyage, and they might not have had the time or managed to implement the necessary changes in order to take advantage of these insights afterwards,” says Dyrdal. Because change takes time.

The researchers are now going to test whether this hypothesis holds water.

“So far, we have only looked at the follow-up data from three months after the voyage. As we now begin to analyse the follow-up data for six and twelve months, we hope to gain an even better understanding of what causes this phenomenon,” says Dyrdal.

The observed decline after returning home is called ‘PSD’ or ‘post-sailing depression’ by the sailing community, and describes the emptiness that may arise when returning home after weeks at sea.

Follow up is crucial

It is not only three-masted tall ships that find it difficult to implement major changes of course.

“We all tell stories about ourselves. These stories help define our perceived scope of action. If I tell myself that I am a shy person who wouldn’t dare to speak in front of a group of people, then I am probably not going to be able to do it,” says Dyrdal.

The research now suggests that the circumstances on board Christian Radich can facilitate the rewriting of such stories. The psychologist says it could eventually lead to new opportunities.

“But it takes time. That is why it is so important what the young people return to after the voyage – that there is someone actually there to follow them up and help them build on what they learned about themselves during their voyage.”