A Post-Nuclear Deal Iran Prepares For Elections – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

The Iranian political landscape is multilayered, with a juxtaposition of conservatives, moderates, liberals, the military, intelligence and others fighting to build influence zones within the polity.

By Kabir Taneja

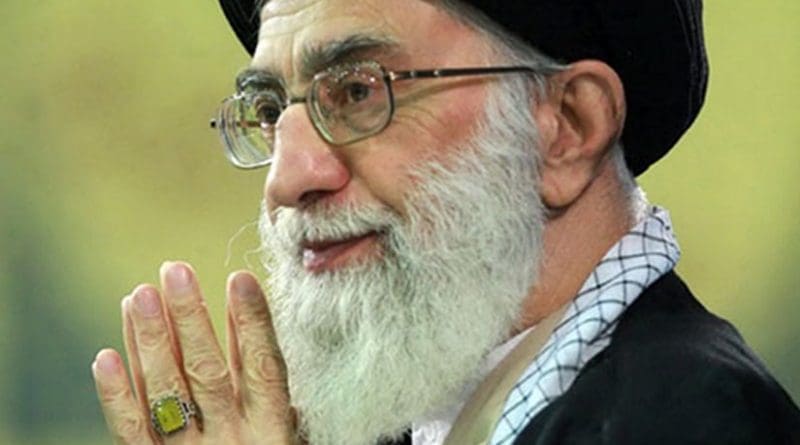

Iran has kicked-off its month long election campaign with the announcement of the finalists approved by the supreme leader of the Islamic republic, Ayatollah Khamenei, after a vetting process orchestrated by the Guardian Council which works under his ambit. Current president, Hasan Rouhani, will be joined by competitors Mostafa Aqa-Mirsalim, Mostafa Hashemi-Taba, Es’haq Jahangiri, Mohammed-Baqer Qalibaf and Seyyed Ebrahim Raeisi to lead Iran in an era of uncertainty, specifically with President Donald Trump at the helm in Washington DC.

The run-up to these elections have already been filled with drama, with former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, despite saying he is not running for the polls, surprising the Iranian electorate by submitting his candidacy during the final minutes of the application process. In total, more than 1,600 candidates applied to contest the elections, including 137 female candidates, none of whom made the final cut.

President Rouhani, under whose guidance Iran agreed to the critical nuclear agreement with Western nations (all United Nations Security Council members plus Germany), according to analysts, will have competition from quarters of Tehran politics that he is very familiar with. His competitors can be divided into two groups, the reformists and the conservatives. First Vice President Jahangiri and former minister of mines, Hashemi-Taba along with Rouhani are from the former grouping. The conservatives are represented by the Mayor of Tehran Ghalibaf, former minister of culture and Islamic guidance Mirsalim and the odd candidacy of Raeisi, who is the custodian of the holy shrine of the eighth Shiite imam, but more importantly, touted to be a potential replacement for the now ageing Ayatollah Khamenei himself.

Popular expectations are that Rouhani, Ghalibaf and Raeisi are to be the electoral leaders in a race that is going to reflect both the political and economic outcomes of the post-nuclear deal Iran. According to a recent poll conducted by Canada based consultancy IranPoll, the economy and jobs are the foremost areas of concern that the people of Iran want their leaders to address, the same issues that were flagged before the previous elections and the subsequent swearing in of Rouhani as president. According to the poll, 52% of the participants of the modest 1,005 Iranians who took part in the study said that the economic situation in the country under the leadership of Rouhani was getting worse, while 31% agreed that it had gotten better. On a narrower question, when asked whether the economic situation of ordinary people had improved due to the successful negotiation of the nuclear deal, 72% replied in a negative tone saying that it had not improved.

The nuclear deal’s effect on the elections may be a red herring. Similar to the situation prior to the election of Rouhani in 2013 that ousted Ahmadinejad, under whom Iran’s ties with the West hit a new low, joblessness amongst the youth and lack of economic upliftment became the key political issue in Iran. Years of Western sanctions had rendered the Iranian economy severely strained, which in return gained public support in the country for its governance to thaw relations with the West. This was used by the moderate and reformist political circles in Tehran against the conservatives who, throughout the negotiation process, criticised Rouhani and Foreign Minister Javad Zarif for giving too many concessions to the West in return for Iran’s basic rights to develop civil nuclear energy resources. Even Ayatollah Khamenei often took to Twitter; the social media site banned for common Iranian citizens, to threaten the US even as Iranian delegations were in Vienna, Austria, negotiating the agreements.

The Iranian political landscape is multilayered, with a juxtaposition of conservatives, moderates, liberals, the military, intelligence and others fighting to build influence zones within the polity. The premiere example to illustrate this is decoding the role of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard’s Corps (IRGC), a highly trained military structure directly under the command of the Ayatollah, tasked with protecting the Islamic revolution itself from foreign interventions and internal dissent.

However, the IRGC is now also heavily involved in the Iranian economy and is known to have ownership of various companies and state enterprises in fields such as construction, telecom, mining and so on. In January this year, the Iranian government along with entities closed to the IRGC signed commercial deals with the Syrian government for assisting the Bashar al-Assad regime in the Syrian war. As much as the conservative or reformist power blocks, including former presidents, matter in the outcome of the elections, the extension of the military/intelligence apparatus into electoral posturing has perhaps grown in Iran over the past few years it was under Western sanctions.

This also gives Raeisi a good chance at the presidency. Despite popular understanding seems to point towards the re-election of Rouhani, the conservative lobby along with the intelligence sector, made few qualms about its reservations over the nuclear deal known. This in effect could give the likes of Raeisi a well-orchestrated and strong bogey against the reformists club that backs Rouhani, which now includes the likes of former president Mohammad Khatami, a pro-reforms leader himself who led the Iranian government from 1997 until 2005. Such an endorsement could be of pivotal importance, as Khatami, like many of his predecessors and successor Ahmadinejad, had a falling out with the Ayatollah in his post-president years and was banished from politics.

India, one of Iran’s largest buyers of oil across the Arabian Sea, has had a relationship with the country that has been both fruitful and fractured simultaneously. Oil and gas has featured as the top most priority of the Iranian economy, and by extension, critical to political stability of the country. India and Iran are home to civilisational ties spanning thousands of years, and despite the relationship being cordial and consequential; it has more than often found it hard to develop an all-encompassing working diplomatic understanding between the two. Despite India voting against Iran at the UN over the latter’s nuclear program in 2009, predominantly under US pressure, New Delhi pushed for Washington to give it concessions from international sanctions against Iran on order to continue buying oil from the country. Along with this trade, India also committed more than $1 billion in Iran’s Farzad B oil and gas field, which has been embroiled in traditional bureaucratic entanglements that have become definitive of the bilateral dynamics between the two countries.

Beyond oil and gas, the possibility of greater strategic engagement between the two countries relies on the Chabahar port project. During previous high-level ministerial visits by Iran to India and Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Tehran last year, the mirage of the Chabahar project’s strategic importance to India has been even more elevated despite the fact that the entire dance between the two countries to develop it has been an excruciating display of bureaucratic red tape. Attempts to push forward the development of Chabahar is today an excellent, systematic and step-by-step guide on how to fail at diplomacy where both parties stand to gain significantly on their respective interests, yet fail to establish the same. India’s interests span a far-searching policy attempt, with Iran also being crucial for stability in Afghanistan and providing access to Central Asia, while Iran is perhaps yet to recognise that most of its markets for hydrocarbons for the next three decades lie towards the East.

From an Indian perspective, re-election of Rouhani could perhaps see a continuation of the stalemate between the two countries over critical issues, which now includes a war of words over the Farzad B oil and gas field as well. However, it is in India’s interest that Tehran remains on a reformist path, and the Iranian economy continues its movement towards an open market attached to global trade. While it is true that the election of Donald Trump as president of America has thrown many uncertainties over investing in Iran, the fact that the nuclear agreement is a multi-dimension one involving five other powers could be seen as both a balm and safety net over fears of an American withdrawal from the agreement.