On Mexican Border: Triangle Resident Receives Education From Immigrants Hoping To Settle In US – First person

Sir, I have to ask for help. Could you print my I-94 so I can prove I entered legally?

At the door of Annunciation House here in El Paso, I see a very pregnant woman with pink nails, frilly running shoes, and a pink parka. In rapid-fire Cuban Spanish, she is asking me for a copy of the I-94, the Arrival/Departure document from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. She says she needs the paper since it is the only document to prove she entered the U.S. legally. I ask this woman—her name is Delia—why she walked instead of coming on the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) bus that delivers hundreds of immigrants every day. She says ICE refused to let her bring her pit bull and she won’t abandon her dog. I tell her that, since she did not arrive on an ICE vehicle, I cannot admit her but that I’ll call a volunteer to print her I-94.

While waiting for the I-94, we prop our elbows on steel railings and Delia tells me how she fled Cuba by taking a boat to Guyana on the northeastern coast of South America. Then she and her husband embarked on a two-year odyssey that ended in El Paso.

I worked my way across 15 countries by painting nails. Fifteen! My husband is a barber and cuts hair, so we saved a lot of money. Pesos. Quetzals. Do you realize that almost everyone wants their nails painted or hair cut? And colored, too. We had so much time that we planned our Miami nail salon and barber shop. My husband almost got killed, though. In Mexico, he met some narco-traffickers who wanted a personal barber. My husband agreed but kept offering cuts to others, too. When the narcos told him to serve them only, my husband said, ‘Fuck off!’ They broke his nose, so we fled, hitchhiking to the Texas border.

“Did ICE let you enter?” I asked.

We got a “lawful entry” so we can be in the U.S. But then I had a problem because ICE did not like my pit bull, Chanel. I think Chanel smells wonderful, but ICE kicked us off the bus. I had to walk hours from the bridge to here.

“How did you get the dog,” I asked, “if ICE was detaining you?”

Delia laughed.

When I was still in Mexico, my brother devised a plan. He was already in the U.S. and stood in a parking lot next to the Rio Grande. He waved dog biscuits at Chanel, and Chanel ran across the dry gully, from Mexico into his arms in the U.S. When I got across, he handed me my dog. ICE got angry and stopped me from boarding that bus.

The more I talked with Delia, the more I was convinced that the U.S. should welcome her and her husband. Her journey was hard, but she has remained optimistic, tough, persistent, funny, and kind. She reminds me of my great grandfather, another optimist. He fled European wars only to encounter debt peonage and anti-Semitism. Like Delia, he persisted.

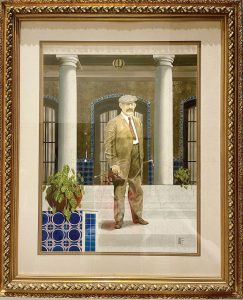

The immigrants’ road is rough. Many of us happily employ immigrants but our system rarely offers legal status or citizenship. Some immigrants have been murdered, including my great grandfather, who, in 1910, was shot in the back by a man who hated Jews. During his short life, Ernst Kohlberg was an entrepreneur par excellence. After three years in debt peonage, he bought his freedom. His gold mining ventures in Mexico failed, but he bought two hotels, started a bank, and built cigar factories in El Paso and Philadelphia. Millions of Americans smoked his Selectos that, of course, were filled with the finest Cuban tobaccos. His creative energy was legendary, and it is no surprise that he is featured in The Wonderful Country, a novel by Tom Lea. Today, he is remembered with a plaque in the synagogue he founded, Temple Mount Sinai, and in the Hotel Paso del Norte, where his portrait hangs next to one of Pancho Villa. He built a palatial home that was completed just before his death. Nowadays, curious descendants like me visit the University of Texas in El Paso to see archived letters Kohlberg wrote about how a cowboy town morphed into a modern city.Expand

I used to think the U.S. should block most of today’s immigrants. Thanks to seven years of teaching ESL classes, interviews in El Paso, and visits to detention facilities, I have changed my mind. This was not a sudden development. Rather, my views broadened over several years and were deeply enhanced by my time at Annunciation House. I see that immigrants are idealistic, tenacious, and courteous. They have qualities I would seek in an employee or neighbor. Companies throughout the U.S. are desperate for workers. Instead of vilifying immigrants, why not pass laws that provide work visas and paths to citizenship for the millions who cut lawns, clean hospitals, build roads, operate food trucks, and construct homes?

In El Paso, there are “help wanted” signs everywhere, and in Juarez, a mile away, there are Mexicans and Central Americans ready to work but unable to cross. Many immigrants have the traits that we want in an employee: willingness to work hard, dependability, punctuality, and determination. Do we really need a southern border? If we allow goods to cross freely, why not labor? What about the law of supply and demand? Why not welcome those who are ready to work? Today, residents of the 50 states, including millions without legal status, travel around the country without state border checks. Why not remove the border checkpoints and the wall?

The wisdom of opening borders is accepted in most of Europe, and, today, when a German drives into France, no one asks to see their passport. Isn’t it time to end our hostility towards the nations that provide the men and women who we employ as gardeners, carpenters, road builders, and chefs?

At Annunciation House, I speak Spanish, French, and Haitian Creole. I interview immigrants and call relatives in far-off cities. I fill out forms, pass out hand cleaner, mop up vomit, and change diapers. When someone has a positive Rapid COVID Test and breaks down in tears, I learn to adjust. A co-worker named Shawn reminds me of Confucius’s words: The green reed which bends in the wind is stronger than the mighty oak which breaks in a storm.

As I witness the nobility of the immigrants I meet during my time here in El Paso, I feel called to serve. Immigrants are assets to our souls and our futures. I am proud of my great grandparents, and I am proud of the people who cross the Rio Grande. Americans are the descendants of immigrants, and, like the men and women from centuries past, the new arrivals act generously in ways that make me weep.

Sunday

Forty-three years ago, Ruben Garcia, 70, founded Annunciation House (AH). Today, AH’s largest facility is the Casa del Refugiado, a former blue jeans factory where immigrants released by ICE and the Border Patrol are welcomed by volunteers. After a day or two, the refugees travel by bus or plane to the homes of relatives where they will live until their deportation hearings.

Located in El Paso a couple of miles from the Rio Grande, the 125,000 square-foot building houses hundreds of cots, a kitchen, and a canopy for COVID testing. The building is so gigantic that it took me a week to figure out how to get from the front door to the office. It offers a dispensary, clinic, and showers.

With gray hair and twinkling eyes, founder Garcia looks like a benevolent uncle. In his welcoming speech to me and other volunteers, he talks with a measured kindness. He seems like the perfect foil to those who insult migrants and block their entry.

Welcome to Annunciation House.

There are about 70,000 refugees waiting in Mexico, of whom some 26,000 qualify for an immigration hearing in the U.S. What happens before they get here? ICE and the UN prepare manifests so that refugees are ready for transportation to a relative’s home in the U.S. A few months later, they appear before an immigration judge and present reasons why they should not be deported. About 60 percent have no legal representation and need an advocate. These days, politics is affecting everything, and this is a real tragedy. Texas governor Greg Abbott is following the Trump playbook since he wants to run for president. No longer do we send the governor a Christmas card. Trump did not get all of his wall built, but he got something even better: No. 42. This rule was instituted when he claimed that migrants created a public health emergency, and it means that many are stuck in Mexico for years.

The first rule at Annunciation is ‘no one dies here.’ We are a petri dish, so we wear masks and use hand sanitizer. We do the Rapid Test, but it is not always accurate, so, if someone tests positive, we use the PCR, the gold standard.

We come out of the faith tradition, but we don’t impose our social justice perspective on anyone. We are conscious that the Creator, Allah, and so on identify with the ‘least’ among us. We in this room are not among the least, but we do this work because it puts us amongst them. God resides in that bus in which refugees ride. You volunteers affirm the spirit and soul of this nation. It is what this nation truly aspires to be. I think of Jesus and the apostles and the 5,000 who needed something to eat. Jesus could have said ‘we will feed a few because I have so little,’ but he said, ‘all are welcome’ and the small offering was enough for all.

We say: ‘All who come have a place. Be the light for hope.’ Life here is a joyous set of interruptions. Remember this saying: ‘Blessed be the flexible for they will not get bent out of shape.’

We want volunteers to serve in Juarez, but there is too much violence. In fact, violence is part of the reason I call them refugees. The UN calls them ‘refugees’ but the U.S. government is terrified of using that word, because it would entitle them to certain rights. Nonetheless, I use the term, and this drives the U.S. government crazy. I don’t say ‘asylum,’ because that is a status the government grants. I see them as having a status already, because they are fleeing their homes.

Haitians are incredible self-advocates. After all, they have come across the water and through Mexico. This is a tough situation for them. ICE takes away their shoelaces, their clothes, and they arrive here with nothing. Shoelaces? ICE says it stops them from running or hanging themselves. It sucks, it really sucks. What do we do? We keep doing intake, often until 2 am.

Don’t forget this saying: ‘Live in the moment. Share the life of the refugee. You have the chance right now to know the people right in front of you.’

Monday

I clean two bathrooms, load toilet paper, and move boxes of blankets and clothing. A colleague with COPD almost collapses after climbing the steps to the dorm rooms, so we make sure to find him a room downstairs. I wonder if he will stay.

Tuesday

I complete intake forms for a Haitian family of three and contact their relatives in Florida. I end up using three languages in addition to English to arrange tickets for the 62-hour trip.

I interview a Honduran mother and daughter. They waited in Juarez for two years, but today they will take a bus to Austin, Texas. I welcome them to the U.S. and tell them I am glad they are safe. They smile timidly. It occurs to me that very few people have said a kind word to them in the past few months. My job is to be friendly, harm no one, and find a safe harbor.

Wednesday

A dust storm blows through El Paso, making it nearly impossible to see anything on Interstate 10. A Honduran tells me his relatives refuse to pay for the bus ticket, so his family is stuck. Forty Haitians, Cubans, and Hondurans arrive. The Cubans don’t have ankle bracelets, many have new clothes, and one even has a multicolored bouffant hairdo. Another has a mohawk. Our shift supervisor welcomes the new arrivals, but three Cubans interrupt and ask to be taken to the airport. They have already arranged flights and do not want food, cots, or intake. They are ready to fly to Miami, so we print the I-94s and send them on their way.

Thursday

I talk with Marie, a Haitian woman whose husband was detained. Today, single women and couples with children are allowed in. Marie is seven months pregnant, but her husband must stay in detention. Our nurse discovers that Marie has a urinary tract infection, so I explain in Creole that she should take antibiotics. I am unsure she understands. I call the lawyers at Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center and complete the intake paperwork for the husband. I have no idea if he will be released before Marie heads to the airport. What will happen in the Dallas airport to a woman in pain who speaks no English and who is ready to give birth?

Marie’s husband was detained after he lawfully entered the United States. This peculiar injustice reminds me of the first detainee I ever met. Her initials are Y.M., and I met her at Eloy Detention Center in Arizona. Since Y.M. had never had a visitor, Tucson’s Unitarian Universalist church arranged for me and my wife to go to Eloy. She sobbed as soon as she saw us. She told us that, at the border, she asked for asylum; ICE told her that she had the right to apply but that she would be in detention first. She languished there, utterly isolated. After our emotional visit, I sent her ESL books, commissary money, and jokes in Spanish. She and other women taught each other and formed a community. She was thrilled to learn some English phrases and sent us monthly letters the old-timey way, on paper. We called an Arizona law office and, after almost two years in prison, Y.M. flew to Louisville, Kentucky. Now, she is working at an automotive factory and applying for asylum.

Friday

This morning Ruben speaks to the new arrivals.

Welcome. How many were in Juarez for two years or more? Wow. You could get old there! No danger here. We are not “la migra.” You can stay here or in a hotel. If you leave the building, you can’t return here because of COVID. Don’t do reservations on your phones please. We will give you meals. We are all volunteers to help. When you get to where you are going, get a lawyer. Agreed? Immigration will try to deport you. You must have a lawyer so as to improve your chances of being allowed to stay. The press is here and if you want to be interviewed, raise your hand. Anyone kidnapped in Juarez? No one? OK.

I do intake for a family from Honduras. The 18-year-old son has thick glasses and says he wants to be a doctor. The mother tells me that merciful God has protected me, and because of his blessings, I am here.

Saturday

I practice imitating Ruben’s welcome speech, and, today, I am asked to give the talk to a new group.

“Welcome. We are happy that you are here. We want you to know we feel honored to know each of you. Bienvenidos, todos! We will assist you on your journey from El Paso to the home of a friend or family member.”

People clap and say Gracias! and Bueno! I realize that I am the first U.S. citizen to say anything nice.

“Ahora esta es su casa.” Our house is your house.

“For us, you are a gift. You bring your language, culture, ideas, dreams, and willingness to work. We want to serve you and your families. We will make sure you are safe. You will get a cot, cosmetics, clothes, a shower, and a wash basin. We will help you get to relatives’ homes. It is there that you should prepare immigration paperwork. Contact a lawyer or an agency to assist you. Questions?”

I intake a Cuban woman and ask how she felt when she realized she was in the U.S. She says, Honestly, nothing. I was numb; it was so unexpected. I didn’t know what to think, so I didn’t think. Now I’m here and I still don’t know what to think.

Monday

I interview Yoli, a Guatemalan from San Marcos, the very town in which my Guatemalan-American son was born. Silently, I think that if I had not adopted my son, Marco might be sitting in front of me today. Yoli speaks Mam, a Mayan language, is 28 and has four children. She tells me that her drunk husband was incapable of taking care of the children, so she fled with two of her kids, leaving the others with her mother. She teaches me how to say hello by touching hands and tapping my face. I appreciate this tender gesture so much that I can barely murmur “gracias.”

Marta, also a Guatemalan, is next. She left her home eight days ago and traveled by bus and train to Juarez. She tests positive with the Rapid Test, so she and her daughter have to move into quarantine. She bursts into tears and says that the delay is too much to bear. I assure her that she will not be deported during the next 10 days, but I feel helpless. I want to offer something but all I can do is sit and listen.

Tuesday

I meet a Honduran, Dia, and two of her friends. After getting their bedrolls, they grab yellow buckets and mop the vast floor.

“Thanks!” I say to Dia. “Want to take a break?”

No, we got to get it done.

“When you’re finished,” I tell her, “let’s get some shoes to replace your flip flops.”

OK.

Later, I take them to the clothing room, and they search through piles of shoes on dozens of shelves. A volunteer comes in and scolds me, Soon, everybody will come in here and take garbage bags full of stuff.

“No discussion necessary,” I say. “They need shoes for the cold bus ride and we have hundreds.”

It turns out that Dia is a teacher and much better educated than many. She opposes the president’s political party, so she cannot get work. She tells me that her mother had six siblings, four of whom died at birth. Only a brother survived, but he contracted polio. His arms are rigid, and her mother spoon-feeds and clothes him. Years ago, Dia’s brothers made their way to Virginia to raise money for their stricken uncle.

Even though her life seems overwhelmingly difficult, Dia says, I’ve been watched over by angels. I crossed the border on my first attempt, but many others were deported.

I am so impressed by Dia, her family story, and her mopping that I ask if there is anything else she needs. She says she lost her cell phone, so, against the AH rules, I go to Walmart and buy one and pay for the plan. By the time I get back to AH, Dia has found her phone and so I still have an extra.

Later, I call her a few times in Virginia to see how she is doing. No one answers.

Wednesday

A group of detainees arrives from Laredo, but they can’t get off the bus because the COVID testers haven’t arrived. Kneeling on the bus’s stairs, I chat with Border Patrol drivers who have embroidered patches saying “Mr. Rodriguez” and “Mr. Ruiz.” They announce that they are ready to retire so they can explore new hobbies.

Guess what I’m going to do?, Mr. Ruiz asks me.

“Hmmm. I have no idea. Fishing? Sailing? Camping? RVing?”

No. You’ll never get it in a million years. Give up?

“Racing cars on a dirt track? Paragliding? I don’t know.”

Dude, I’m gonna have SEX! Lots of sex, sex, and sex!

“OK! Well, that is something!” I say.

Told you you’d never guess.

“You’re right! Hey, you guys seem like great friends.”

We’ve relied on each other for 15 years. We’re buddies.

I look through the grimy, translucent barrier that separates us from the passengers and ask, “Who’s getting off the bus?”

They were flown in from the Rio Grande Valley. They get to keep their clothes. We ran out of sweatpants and T-shirts.

“Any problems today?” I ask.

We don’t have problems. Hey, we gotta go! Stay young!

Thursday

I help a mom dispose of soggy diapers, and I clean up an infant’s vomit. A man cannot figure out an airfare, so I show him the current price on the internet. I am irritated that there are things we can’t change. A one-year-old has a fever, but we cannot give him Tylenol. Almost no one has money, but we cannot give out cash.

A woman squats on her bed and tries to pull off her skinny jeans. No matter how hard she tugs, she cannot get the denim to slide over the clunky, black ankle monitor. She starts to cry.

“Excuse me. Any way I can help?” I ask.

Cut my jeans! I can’t get them off. I have to wash them. This grillete (shackle) won’t let me take my pants off.

“Tell you what. Pull your pants back on and we’ll find a woman who has scissors,” I say, having no idea which volunteer to approach. We go to the office, and a colleague quickly takes out a pair of scissors and rips the seam halfway up to the woman’s knee. The two women smile.

Friday

I learn to ask if women want “feminine towels.” Few can afford to be discreet about the body, especially the women who breastfeed and all those who make sure to leave the bathroom door open.

We get a busload of depressed, smelly people. It turns out that officials took their street clothes, and the immigrants were flown from Brownsville to El Paso. Of all the things I don’t understand, this is the most confounding. Why does our government (that is, the taxpayers) fund planes to fly 800 miles across Texas and then deport most of them?

Saturday

I realize it is time to leave Annunciation House, at least for now. I recall tense discussions with other volunteers. Who gets priority with clothing and first aid? How does the chlorine sprayer work? Despite hassles, we recognize we are serving brothers and sisters in need. We are blessed with the opportunity to welcome the newest among us.

Among the volunteers, there were sharp disagreements, so I was touched to get a ‘thank you’ from colleagues. One wrote, My man, it has been such a gift to have you here. I appreciate and love so much your hilarious sense of humor, your empathy, and care for both the guests and fellow volunteers, and just your presence in a room. I’m gonna miss you, dude, and may our paths cross again.

Another said, It was wonderful to work with you, welcoming our kin on the border. Thank you for sharing so much in so little time. Bendiciones y buen viaje. (Blessings and have a good trip.)

It is hard to imagine anything more inconsistent than U.S. immigration laws. During the thousands of years that Native Americans inhabited the Americas, there were no restrictions. For most of the time that the U.S. has existed, there were no restrictive laws. Many laws passed by Congress, like the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, were unjust and, in recent decades, have resulted in over 12 million people living in a legal limbo. Immigration restrictions are a blot on American history, akin to the Japanese-American internment camps.

My experience here at Annunciation House makes one thing abundantly clear: It’s time to reform the system.

*While volunteering at a refugee center in El Paso, Craige came to appreciate what life was like for his great grandfather, Ernst Kohlberg, who arrived on Ellis Island in 1875. Due to experiences in Texas and North Carolina, Craige is becoming an Accredited Representative, so he can advocate for immigrants in court. After a career in public schools, Craige is teaching Civics and English as a Second Language at Durham Technical Community College.

Source: This article was published at Indy Week and is reprinted with permission.