Persian Cultural Nostalgia As Political Dissent – Analysis

By Sarah Katz*

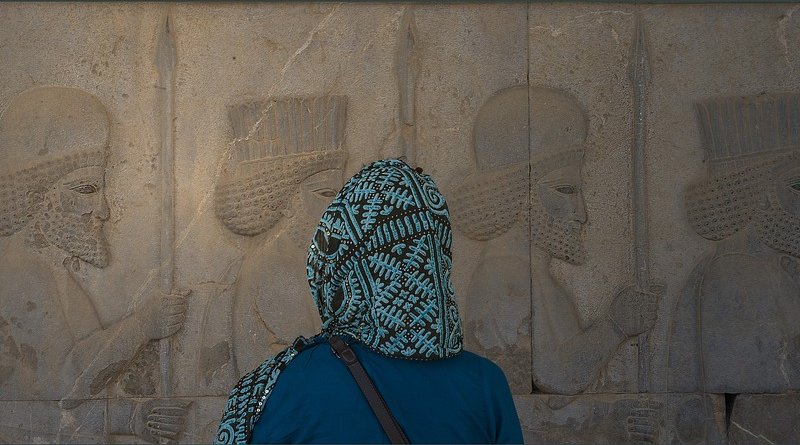

Since the founding of Iran’s Islamic Republic in the wake of the 1979 revolution, the government in Tehran has smothered the country’s rich, diverse, and ancient culture beneath a theocratic dictatorship. The regime is openly contemptuous of Iran’s history, its ethnic and religious minorities, and its secular-minded citizens. It enforces its own rigid Islamic values in a variety of ways, from requiring women to cover their hair to imposing religious principles in schools.[1] Repression has resulted in various social issues among Iran’s youth, such as drugs and prostitution.[2] As a result, nostalgia for the Persian Empire’s pre-Islamic past legacy is steadily rising, especially among Iranian exiles and their children in the United States. Washington would be well advised to take note of it and understand what it may portend for the future.

Islamic Conquest

The early Islamic conquerors of the seventh century spread Islam and the Arabic language throughout the Persian Empire and attempted a wholesale replacement of the indigenous culture. Over time, most of the country’s population converted to Islam, but Persia’s historical and cultural legacy proved resilient. This fact was so central that when Col. Reza Khan established a new dynasty in 1925, he linked his family to Persia’s pre-Islamic history by adopting the ancient Persian surname Pahlavi for the dynasty. Reza’s son and heir, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, occasioned the October 1971 celebration of his fifty-second birthday, probably the biggest birthday extravaganza in modern times, to coincide with the supposed 2,500th anniversary of the founding of the first Persian empire in the sixth century B.C.E. by the Achaemenids.[3]

That changed in 1979 when the Islamic Republic founded by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini recast Iran as a full-fledged theocracy with a “guardian jurist” (vali-ye faqih) as its supreme leader; spurned Iranian nationalism in favor of a world conquering Islamist vision; and dissociated itself from Iran’s pre-Islamic past, for instance, by Arabizing many Tehran street names from their classical Persian.

The Islamization of Iranian politics and society stirred discontent among the country’s minority groups, which viewed the regime’s policy as designed to suppress their identities, not least given Islamic law’s institutionalized discrimination against religious minorities. Sidelined and marginalized, they have been officially referred to as aqaliyat (minorities) and excluded as the “stranger” or the “other” (gheyr-e khodi).[4]

Many Iranian dissidents—both active and passive, at home and abroad—have responded to this diminished status with a revived Persian pride based on nostalgia for the pre-Islamic culture of classical Persia. Exiled Iranian journalist Amir Taheri and University of Montana professor Mehrdad Kia find evidence of such pride in the desire for purification of the Persian language, the emphasis on Zoroastrian culture over Arab and Islamic culture, and a revulsion against the theocratic government.[5] As University of Toronto professor Mohamad Tavakoli-Targhi explains,

The refashioning of Iran and a rescripting of “the people” and “the nation” in Iranian political and historical discourses was to take place through a selective remembrance of things pre-Islamic and a disassociation of Iran from Islam.[6]

Many Iranian nationalists and scholars hope to de-Arabize the Persian language to distinguish their ancient culture from the Islamic one imposed by the government. Writes historian Kia:

The dominance of the Shi’ite clergy led some nationalist intellectuals to believe that the cultural hegemony of Shi’ite Islam must be challenged and replaced only by a new form of identity which emphasized Iran’s pre-Islamic history and culture as well as the Persian language and its rich literary heritage.[7]

This scope of pre-Islamic pride has been established via “a linguistic nationalism that became part of a programmatic plan to “purify” Persian of Turkish and Arabic contamination.”[8] Its proponents call for a complete return to the Persian language as it existed before the arrival of the Muslim conquerors.

The experiences of non-Muslim minority groups and the suppression of pre-Islamic sentiment have encouraged some nationalists to rebel with unmistakable love for Iran’s earlier culture. This nationalistic pride has arisen in Iran primarily in response to the establishment of the Islamic Republic rather than in opposition to Islam itself. “Much of this longing for the purity of ancient Persian culture,” writes Taheri, “has arisen with the societal dislike of the contemporary Iranian religious regime as well as the regime’s very aversion toward such pre-Islamic identity.”[9]

Roya Hakakian’s memoir, Journey from the Land of No, is the personal account of a young Persian, Jewish girl caught in the middle of the Islamic Revolution. She describes how many Iranian Jews yearn for a less suppressed and more inclusive Persian culture. “Instead of their given Hebrew names, they went by Persian names, borrowing heroic titles from old myths, like Rostam or Zaal.”[10] She explains further, “With more than two thousand years of history in Iran … Jews were right at home exactly where they were, as they would be nowhere else.”[11]

The Iranian-American Narrative in California

California is home to the largest population of Iranians and Iranian-Americans in the United States.[12] If a mainstream Iranian-American narrative exists anywhere, it will be found here.

This author interviewed five University of California-Berkeley students regarding their views of the Islamic Republic of Iran, U.S. foreign policy in Iran, and their identification or lack thereof with Iran’s pre-Islamic culture. These interviews provide an in-depth look at the opinions of several individual students along with a broader survey of Iranian-Americans in California, discussed below. The surveyed students are first generation, U.S.-born Iranians and are the most likely to represent the views of future Iranian-American politicians and organizers of Iranian-American lobbies. Understanding what they think and why could help reveal where their loyalties lie, a common concern regarding influential figures with dual citizenships and backgrounds.

Interviews

Three University of California-Berkeley students—Shahrzad Makaremi, Tina Noohi, and Taraneh Harirchi—were asked the same questions used in a wider survey of Iranian-American college students throughout California.

Makaremi is one of the founding members and leaders of the UC Berkeley Iranian Students’ Cultural Organization (ISCO). Hailing from a Muslim background, Makaremi’s family left Iran for the United States to pursue better educational and professional opportunities. When asked whether she identifies more closely with the contemporary culture of Iran or with the pre-Islamic culture of ancient Persia and how she views current foreign involvement in Iran, Makaremi appeared perplexed:

I have a lot of interest in the pre-Islamic culture of Iran. It’s quite romanticized, but still very important. Still, it is very difficult to separate Islam from Persia because the Islamic conquests happened so long ago. Radical pre-Islamic pride is misleading, since Islam and Persia influenced each other so much. … Although I am not strongly averse to the Islamic Republic myself, I would say that it has turned off many Iranian and Iranian-American people to the Islamic nature of today’s Iranian government. As far as foreign activity in Iran, such as sanctions, it hurts the people just as much as the government does.[13]

Overall, Makaremi believes that several problems face Iran today and that the regime is not necessarily the worst of them. She does not seem to harbor much opposition to the Islamist regime and does not dislike it strongly enough to favor pre-Islamic Iran.

Similarly, the other leader of ISCO, Tina Noohi, also exhibits a general acceptance of the Islamic Republic. Born into a family of practicing Muslims, she explains that the real conflict is not with the regime’s religious nature but with the political strife that accompanied the revolution and the war with Iraq immediately afterward. These were the reasons her family chose to remain in the United States after pursuing American degrees:

I definitely have an interest in Iran’s pre-Islamic culture and history. It’s part of who I am—the Zoroastrian holidays, like Norouz [Persian New Year]—that’s something the government can never take away. I identify foremost as an Iranian and secondly as a Muslim Iranian. Both my cultural heritage and my religion are part of me as a person. Regarding foreign sanctions, it’s harmful to the people, and it would be best if the U.S. just left.[14]

Like Makaremi, Noohi is opposed to U.S. sanctions. But she makes no connection between her interest in ancient Persian culture and her negative opinion of the current Iranian leadership.[15]

The third respondent and student cultural leader, Taraneh Harirchi, shares her classmates’ perspectives regarding cultural identity, the current Iranian leadership, and international involvement in Iranian affairs. Harirchi does not belong to a religious minority, and she identifies more with pre-Islamic Persian culture despite her family’s Muslim background:

Even though I am technically Muslim, I identify more with the classical Zoroastrian culture of the ancient Persian Empire because I am extremely proud of my culture and not necessarily my “religion.” Both my family and I practice all the traditional Persian holidays, and it is taken very seriously especially around New Year’s time. My family and I never go to mosque or acknowledge any of the martyrs like some religious Iranians do.

On the government and international sanctions, Harirchi said:

For me, the religion largely represents the government, not the Iranian people. As far as sanctions, I believe that they’re very dangerous and only hurt the Iranian people. Foreign involvement is obviously the most debilitating risk to Iran right now.[16]

All three student leaders emphasize their cultural identities over their religious ones. The separation of culture from religion among Iranian-Americans appears to originate from a broadly negative view of the Islamic Republic. However Harirchi, like her two peers, does not view the government as more detrimental than foreign involvement.

The interviewees perceive pre-Islamic culture as important but do not necessarily oppose the regime because of it. One even viewed it as “romanticized.” Still, all state that the Islamic Republic creates problems for Iranian society, from cultural suppression to limitations on education. It is clear from these students’ responses that they do, indeed, oppose the regime.

Statewide California Survey

While the interviews provide some personal details from student activists at a particular university, a survey conducted at the same time used the same questions to gather more data about Iranian-American views of the regime and the extent of opposition to it; U.S. intervention; and pre-Islamic Persian pride. Respondents were polled anonymously from the campuses of University of California, Berkeley, Los Angeles, Irvine, and Santa Barbara; University of Southern California; University of San Francisco; Santa Clara University; San Jose State University; Mission College, and West Valley College.

Seventeen out of twenty-five (68%) expressed pre-Islamic pride and cultural nostalgia in opposition to the Islamic Republic while only five out of twenty-five (20%) identified more with the contemporary Islamic culture of Iran, were not averse to the regime, and considered U.S. involvement to be the biggest threat to Iranian society. Another two participants (8%) favored neither pre-Islamic nor contemporary Iranian culture due to a lack of knowledge while only one (4%) felt pride for both pre-Islamic and contemporary Iranian culture and expressed a strong interest in Iran’s ancient history as well as its current political situation.

As expected given Taheri’s analysis of minority oppression and the Middle East Institute’s Hossein Godazgar’s description of the downplaying of Iran’s pre-Islamic history by the regime’s Islamist educational system,[17] students who identify more with pre-Islamic classical Persian culture also oppose the regime. These students are mainly inspired by the plight of their parents, who fled religious oppression in search of a freer and better future elsewhere. The majority considers U.S. intervention a lesser evil than the regime itself and regards their cultural nostalgia as part of their broader feelings of dissent.

In 2018, the Public Affairs Alliance of Iranian-Americans released an annual survey measuring opposition to the Islamic Republic. It found that by an eight-to-one margin, respondents oppose U.S. support for the Islamist-socialist People’s Mujahedin of Iran (or MEK) party as a legitimate opposition force in Iran while backing Washington’s support for exiled Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi by a two-to-one margin.[18] Opposition by Iranian-Americans to Islamic groups is primarily anti-theocratic. And since Pahlavi states on his social media channels that he supports a secular democracy in Iran,[19] widespread support for him is indicative of the secular route many Iranian-Americans would like to see their ancestral homeland take. Pahlavi’s enthusiasm for Iran’s pre-Islamic Persian history also echoes the cultural nostalgia felt by many Iranian-American civilians.

Pre-Islamic Persian Pride

Additional data published in an article by Nilou Mostofi in The Sociological Quarterly sheds light on the Iranian-American diaspora’s feelings of kinship with Iran, their views of the Islamic Republic, and how many choose to identify with their heritage. The majority of Iranian immigrants, especially in southern California, left Iran in the wake of the Islamic revolution. They tend to be secular and “anti-Islamic,” and most emphasize their pre-Islamic roots by identifying as Persian. Like the students interviewed and surveyed earlier, they left Iran for the United States hoping for better opportunities, professional careers, and education.[20] Estimates place the number of Iranians living in Southern California at 300,000-500,000, with some 87,000 people of Iranian ancestry living in Los Angeles alone.[21]

According to an analysis by Radio Payam, Persian Jewish immigrants in the United States identify with Iran’s classical Zoroastrian culture more than with Iran’s contemporary Islamic culture:

Not identifying themselves with the current Iran—stigmatized by fundamentalism and terrorism—Iranian [web]sites attempt to [re]construct a Persian profile by using tokens, symbols, and signs from the pre-Islamic cultural heritage.[22]

This response is common among Iranians living outside Iran, especially among Iranian minorities.

Conclusion

Following its progression from Iran, pre-Islamic Persian pride in California seems to have merged with American democratic ideals to pit most young Iranian-Americans against the Islamic Republic and some against foreign involvement in the region. And while not all Iranian-Americans necessarily wish for the complete return to pre-Islamic Persian culture, they are proving loyal to both Iran (though not the Islamist regime) and the United States. Indeed, politically active Iranian-Americans who oppose both the Islamic Republic and foreign interference could promote the withdrawal of all financial support from the regime, so as to force it to reform, while supporting the development of a strong, independent Iranian society that will be less dependent on foreign aid.

*About the author: Sarah Katz is a cyber security engineer and author of the Cygnus Award-winning science fiction novel Apex Five. She has been published in AHF Magazine and Cyber Defense Magazine. She was a nominee for the 2018 Women in IT Security Champion of the Year Award.

Source: This article was published by Middle East Forum, Winter 2020

[1] Hossein Godazgar, The Impact of Religious Factors on Educational Change in Iran: Islam in Policy and Islam in Practice (Lewiston: Edwin Mellen, 2008), p. 153.

[2] Amir Taheri, The Persian Night: Iran under the Khomeinist Revolution (New York: Encounter, 2010), p. 319.

[3] Efraim Karsh and Inari Karsh, Empires of the Sand: The Struggle for Mastery in the Middle East, 1789-1923 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999), epilogue.

[4] Ali Gheissari, Contemporary Iran: Economy, Society, Politics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), p. 303.

[5] Maggie O’Neill, Asylum, Migration and Community (Bristol: Policy, 2010), p. 44.

[6] Mohamad Tavakoli‐Targhi, “Contested Memories: Narrative Structures and Allegorical Meanings of Iran’s Pre‐Islamic History,” Iranian Studies, Winter-Spring 1996, pp. 149-75.

[7] Mehrdad Kia, “Persian Nationalism and the Campaign for Language Purification,” Middle Eastern Studies, Apr. 1998, pp. 9-36.

[8] Nasrin Rahimieh, Missing Persians: Discovering Voices in Iranian Cultural History (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2001), p. 78.

[9] Amir Taheri, The Persian Night: Iran under the Khomeinist Revolution (New York: Encounter, 2010), p. 18.

[10] Roya Hakakian, Journey from the Land of No: A Girlhood Caught in Revolutionary Iran (New York: Crown, 2004), p. 179.

[11] Ibid., p. 180.

[12] Maboud Ansari. The Making of the Iranian Community in America (Marietta, Ga.: Pardis Press, 1992), p. 1.

[13] Interview with Shahrzad Makaremi, University of California-Berkeley, Mar. 2012.

[14] Interview with Tina Noohi, University of California-Berkeley, Mar. 2012.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Interview with Taraneh Harirchi, University of California-Berkeley, Mar. 2012.

[17] Hossein Godazgar, The Impact of Religious Factors on Educational Change in Iran: Islam in Policy and Islam in Practice (Lewiston: Edwin Mellen, 2008), p.153.

[18] “National Public Opinion Survey of the Iranian American Community, 2018,” Public Affairs Alliance of Iranian-Americans, Washington, D.C., Oct. 2018.

[19] “Prince Reza Pahlavi Says Unearthed Mummy Most Likely Reza Shah,” Radio Farda, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Prague, Apr. 25, 2018.

[20] Nilou Mostofi, “Who We Are: The Complexity of Iranian-American Identity,” The Sociological Quarterly, Autumn 2003, pp. 681-703.

[21] BBC News (London), Sept. 29, 2012; Los Angeles Times, Feb. 24, 2019.

[22] Shahram Khosravi, “An Ethnographic Approach to an Online Diaspora,” ISIM Newsletter, International Institute for the Study of Islam in the Modern World, Aus., 6.1 (2000): 13.

While Itanians everywhere celebrate their çultural roots, politically-motivated articles dressed up as scholarly efforts are a reminder that Israeli propaganda, like its territorial ambitions, continue to expand.