Deterrence Across The Taiwan Strait Demands A Diplomatic Touch – Analysis

By Charles KS Wu, Lin (Kirin) Pu, and Cathy Fang

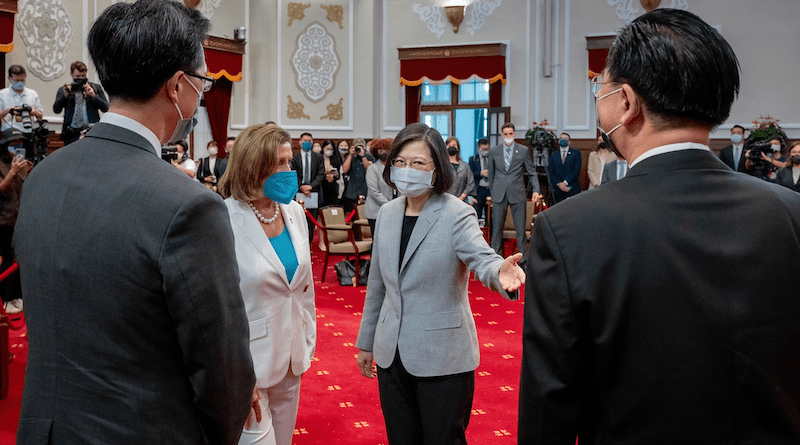

Few observers of US–Taiwan relations would have predicted the monumental events that have transpired in 2022. There was the surprise visit from House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi, President Joe Biden’s commitment to defend Taiwan with US military forces in the event of a Chinese attack and strong support for the Taiwan Policy Act (TPA) in the US Senate.

US extended deterrence, which consists of security treaty commitments and military deployments designed to protect allies, was created as a distinct practice from traditional deterrence. Washington intends to provide billions of dollars in military assistance to Taiwan under the proposed TPA. In addition to building military bases and sending troops to allies, the US government seeks to invest in Taiwan’s defensive weapons capabilities indirectly and enhance the credibility of its threats through diplomacy.

Given the risks associated with military deterrence, diplomatic deterrence can fill in the gaps, especially in the case of the Taiwan Strait. Diplomacy gives the United States more options in its toolbox to support Taiwan, such as encouraging high-level US officials to visit Taiwan and, as the TPA bill proposes, designating Taiwan as a ‘major non-NATO ally’.

This diplomatic strategy is critical because Taiwan on its own can do little militarily against China. The island’s defence has been met with challenges, such as civil–military relations, low popular support for more military spending and resistance to reintroducing conscription. Promised but unfulfilled US arms sales also make it difficult for Taiwan to improve its deterrence capabilities.

After President Biden came to office, it became clear that confrontation with Beijing would not be enough to deter China from invading Taiwan. The US government’s strategy of countering Chinese influence worldwide does little to shift the balance of power across the Taiwan Strait.

At its core, the diplomatic deterrence strategy has two components. The first includes the diplomatic actions the United States has taken in supporting Taiwan in recent years. The second and more crucial aspect is the use of diplomacy to strengthen the island’s defence without directly involving the US military.

Diplomatic deterrence dodges some of the potential drawbacks of pursuing a policy of military deterrence for Taiwan. Its most considerable benefit lies in its flexibility. For example, though President Biden’s pledges could seem destabilising, Beijing has the flexibility to interpret these messages in ways that do not deviate from current policy toward China. This frees China from having to react with overt military force.

Such flexibility was exhausted when Speaker Pelosi visited Taiwan. In response, China blockaded Taiwan with missiles and military exercises for several days.

Still, diplomatic deterrence provides a safety valve and allows Washington to achieve its strategic goals. Parallel to the rhetoric of the Biden administration and the US Congress, other agencies in the United States have been in close communication with their counterparts in Taiwan. These conversations have resulted in tangible progress in the island’s defence, from increasing arms sales to new cooperation between Taiwan’s National Guard and military.

Critics caution that the island could pursue independence on receiving US commitments to defend it. But Taiwan, even after the pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party took office in 2016, has never been the side to change the status quo. Since Xi Jinping came to power a decade ago, China has been more aggressive globally and regionally, militarising islands in the South China Sea and sending warplanes into Taiwan’s air defence zone.

The public in Taiwan is now galvanised, partially by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, to take defence into their own hands. Homegrown efforts such as the Kuma Academy, a non-profit organisation providing civil defence training programs to civilians in Taiwan, have demonstrated how receptive the public is to beefing up the island’s self-defence capabilities.

As the country debates whether to restore its conscription system and adopt an asymmetrical military strategy, visible US support is more critical than ever. A survey in 2022 showed that simply informing citizens in Taiwan that the United States would come to help them in a war created a significant boost in their willingness to defend themselves.

The Biden administration decided to remove some provisions in the TPA that might be considered US diplomatic recognition of Taiwan in Beijing’s eyes, suggesting that the US government remains cautious of provoking China unnecessarily. But the act will still play an essential role in deterrence once it is passed. In addition to military assistance, there are provisions that aim to improve cultural and economic exchange between Taiwan and the United States, such as the creation of a Taiwan Fellowship Program.

Deterrence requires consistent and visible demonstrations of US political resolve and military capabilities. A pledge by the United States to use military force to protect its allies and partners from potential adversaries makes sense. But as Washington confronts growing challenges from China on all fronts, it must prioritise diplomatic deterrence.

In evaluating the upcoming TPA, it is more important to examine its impact from the rhetoric surrounding it.

About the authors:

- Charles KS Wu is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of South Alabama.

- Lin (Kirin) Pu is PhD student in Political Science at Tulane University. He has worked for the Institute for National Defence and Security Research and National Security Council, Taiwan. Pu is also a member of the Formosan Association for Public Affairs.

- Cathy Fang is MA student in the international affairs program at George Washington University.

Source: This article was published by East Asia Forum