Illusions Versus Reality: Turkey’s Approach To Middle East And North Africa – Analysis

By FRIDE

By Soli Özel and Behlül Özkan*

When the Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power in Turkey in 2002, it was able to build upon an emerging regional role to create a new, multifaceted Turkish foreign policy brand. Having positioned itself as a regional mediator during the first decade of the 2000s, by the time of the 2011 Arab uprisings Turkey had shifted its role towards a more intrusive style in dealing with its Middle Eastern neighbours. Four years later, Turkey’s once so promising regional standing lies in ruins. Ankara has lost its gamble on Islamists holding power in transitioning neighbours; has discredited its discourse on the need for democratisation across the region as a thinly veiled hegemonic

ambition; and has squandered most of its regional geopolitical capital.

THE GENESIS OF TURKEY’S CURRENT GEOPOLITICAL PARADIGM

The end of the Cold War freed Turkey from a dependent relationship on its Western allies and reinvigorated Ankara’s urge to be a ‘lone wolf ’ exploring, during the Presidency of Turgut Özal, what Malik Mufti from Tufts University has called an ‘imperial paradigm’ for its foreign policy. Economically driven, and carefully calibrating Turkey’s existing alliance relations and the opportunities offered by the post-Cold War environment around Turkey, Özal’s policies tried to free Turkey of its heretofore timidity in foreign affairs.

When Ismail Cem – Turkish Foreign Minister from 1997 to 2002 – took office, he announced that his goal was to make Turkey a state with global influence. By the end of 1999, the alignment with Israel since 1996 had beefed up Turkey’s intelligence and military capabilities, and when Turkey demanded the ouster of PKK (the Turkish Kurdistan Workers Party) leader Abdullah Ocalan and threatened Syria with war, Damascus was forced to let him go. Turkey’s rapprochement with Greece was well on track. Ankara also started to take serious steps towards European Union (EU) membership, and in 1999 the EU declared Turkey a candidate for EU accession. Ankara was now in a position to make overtures to Damascus since Ocalan was in jail and the war with the Kurds was effectively over. Cem was actively working to mediate in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Relations with Iran were also rehabilitated as economic interests brought the two neighbours closer together. In short, Turkey seemed to enter the new millennium with a much more active and constructive regional foreign policy.

The 2001 terrorist attacks in the United States (US) made the ‘Turkish experience’ (a secular, democratic, economically globally integrated country with a Muslim population that was a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation and sought membership in the EU) exceedingly attractive as a partner and ally. The aftermath of the 2003 Iraq war, which Turkey, now under AKP leadership, did not support, created an unexpectedly propitious environment. Against the jihadist dystopia of al-Qaeda, the Turkish alternative presented a viable synthesis of religious conservatism and democratic liberalisation. At the same time, because of the failures of the Iraq war and its destabilising impact in the region, the US needed Turkey’s weight as a balancing force. Finally, important domestic business constituencies of the AKP, in search of new markets, favoured closer economic and social relations with the Middle East. The AKP’s ‘zero problems with neighbours’ principle along with the concept of ‘strategic depth’ responded to these requests.

THE MIDDLE EAST AS TURKEY’S HINTERLAND?

The first decade of the 2000s was a golden age of Turkish ‘soft power’ in the Middle East, (further boosted by the immense popularity of Turkish soap operas throughout the region). During this period, Turkey’s foreign policy motto of ‘zero problems with neighbours’ seemed a viable strategy. Turkey marketed itself as an impartial ‘mediating actor’ in the region’s conflicts, such as Israel-Palestine, Israel-Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq.

Enjoying growing influence in its new neighbourhood, Ankara pursued cordial relations with a broad range of players in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. These included close ties with Syria and Iran despite tensions with Washington over such policies. While seeking good relations with Tehran, the AKP all the same tried to balance Iran’s expanding influence in the region following Washington’s misadventure in Iraq. Until Israel’s 2008-9 Operation Cast Lead in Gaza, relations with Jerusalem were also close, and Turkey helped set up indirect talks between Israel and Syria.

Pragmatism informed Turkish foreign policy choices, even if a preference for ideologically kindred spirits also motivated some policy makers. Prime Minister Erdoğan’s furious response to the 2008-9 war in Gaza and the May 2010 attack on a Turkish aid ship, Mavi Marmara, in which 10 Turks were killed by Israeli soldiers, led to a dramatic cooling of diplomatic relations. The immense popularity of Erdogan’s anti-Israeli stance among Arab publics inspired the AKP to cash in on this popularity and build further domestic political capital with the broader Turkish public.

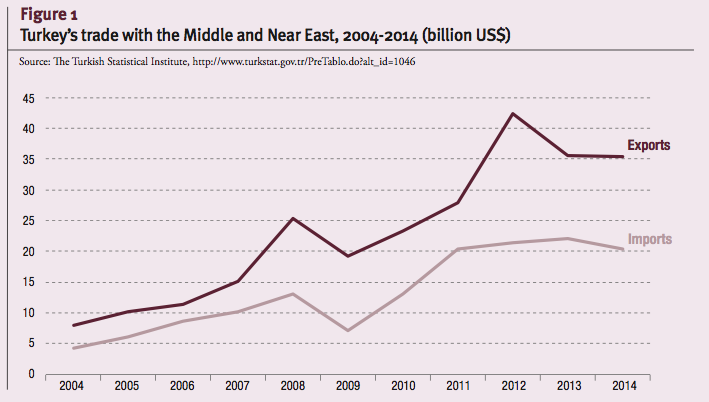

During its first term, the AKP focused on building close ties to the EU and promoting economic integration with Middle Eastern nations. This resulted in a trade boom in the years after 2002. Turkey’s trade with the Middle East, which stood at US$5 billion dollars in 2002, had multiplied eightfold by 2011, reaching US$43.5 billion (see Figure 1).

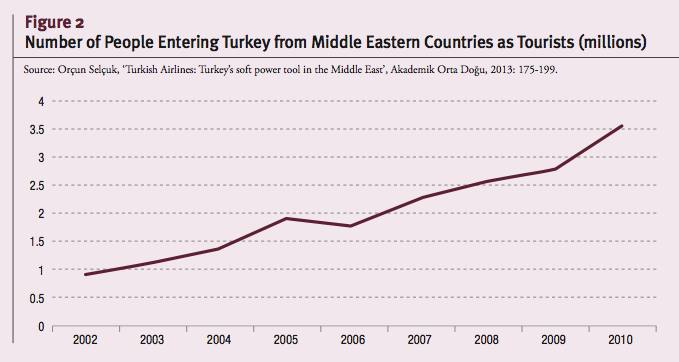

During the same period, the Middle East’s share of Turkish exports increased from 7.2 per cent to 18.9 per cent. Turkey’s reciprocal no visa agreements with Middle Eastern countries from Syria to Libya, which started in 2009 with Syria and gradually expanded, fuelled a rapid rise in the number of Middle Eastern tourists visiting Turkey, from 957,000 in 2002 to 3.57 million in 2010 (see Figure 2).

The appointment of foreign policy advisor Ahmet Davutoğlu as foreign minister in 2009 was a turning point for Turkey’s Middle Eastern policy. By the time of the 2011 Arab uprisings, Turkey was no longer describing itself as a ‘mediating actor’, but as an ‘order instituting actor’. This signified a shift from the careful approach of treating the region as a ‘zone of interest’ to seeing and treating it as a ‘zone of influence’. The latter implied a more intrusive style in dealing with neighbouring states. Davutoglu’s foreign policy goals for Turkey, laid out in detail in his 2001 book Strategic Depth, formed the backbone of Turkey’s Middle East policy for the following decade. For instance, Davutoglu told the Turkish Parliament in December 2011:

‘We are trying to implement this ‘strategic depth’ in order to make Turkey a global actor […] this is the essence of the foreign policy which we are attempting to put into practice every day’. Unlike traditional Turkish statecraft, Davutoglu’s vision was imperious, depicting Turkey as the successor of the Ottoman Empire which ruled over the Balkans, Caucasus, and Middle East for five centuries. Accordingly, Davutoglu defined these territories as Turkey’s ‘hinterland’.

According to Strategic Depth, the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in 1918 and the emergence of ‘artificial’ Arab nation-states were the main causes of the political and economic disintegration of the Islamic World. However, Davutoglu saw these triggers merely as having opened a century-long ‘parenthesis’ in the Middle Eastern order, which was now coming to a close. The Middle East, he held, was bound to witness democratic revolutions like those of post-Cold War Eastern Europe. Dictatorships like Egypt, Syria, and Libya, and monarchical regimes like Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and the Gulf states, that lacked popular support would be unsustainable. Although the AKP’s policy in practice was largely pragmatic in its dealings with Middle Eastern regimes and accepted the regional political status quo, Davutoglu’s vision was inherently revisionist. For a country like Turkey that had been a status quo power since its inception, that position was revolutionary and potentially disruptive.

THE MIRAGE OF OPPORTUNITY OF THE ARAB UPRISINGS

Davutoglu’s strategic view was that Turkey should enhance its prestige with the peoples of the region by establishing close economic ties with Middle Eastern autocracies. But once the winds of change had begun to blow, Turkey should back ascendant Islamist parties, which enjoyed widespread support across the Middle East. Davutoglu held that it was impossible for Turkey, a non-Arab country, to hold sway in a Middle East beholden to Arab nationalism. Accordingly, prior to the Arab uprisings, Turkey supported Islamist parties and regimes wherever they operated. Ankara forged ties with the Islamist regime of al-Bashir in Sudan. It provided critical support to Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated parties such as the Iraqi Islamic Party and Hamas in Palestine. Wherever such parties were in a precarious position, on the other hand, Turkey bided its time, establishing friendly relations with dictators like Assad in Syria, Mubarak in Egypt, and Gaddafi in Libya.

Davutoglu saw the overthrow of Ben Ali in Tunisia and Mubarak in Egypt in 2011 as the start of the long-awaited transformation of the Middle East. Once the initial hesitation vis-à-vis these transformative events subsided, Turkey started to behave as a revisionist, ‘order-instituting actor’ that would bring about the ascendancy of political Islam throughout the region. Yet the seeming moment of triumph that the Arab revolts were meant to be turned into the demise of the carefully calibrated Turkish image and record instead. As the AKP proved unable to suppress its regional hegemonic aspirations, the ambitious foreign policy it had forged began to unravel. Indeed, hubris had led it astray. The ‘Turkish model’ that nearly all major international players evoked at the beginning of 2011 turned out to be a mirage. International hopes invested in Turkey for guiding the emerging regimes on the path of moderation, inclusiveness and openness were bitterly betrayed.

Ankara’s wise policies of earlier years such as remaining above sectarianism, not intervening in domestic affairs of neighbours, calibrating the language of foreign policy with care and regard for others’ interests were precipitously dropped. Nowhere was this deterioration of patience more visible than in Syria. After futile attempts to convince Bashar al Assad to liberalise, Turkey took an unbendingly bellicose line against the Ba’athi regime. Not only did it criticise the regime’s violence, it chose to become the midwife of the opposition in order to facilitate the rise of the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood as a relevant political actor.

Ankara, along with Qatar and Saudi Arabia, supported the Free Syrian Army, favouring the Muslim Brotherhood component and thus became party to its neighbour’s civil war. Acting in concert with oppressive regimes like Saudi Arabia and Qatar, though, seriously undermined Ankara’s own claim to be the agent of democratisation in Syria.

In its haste to oust the Syrian regime, the government chose to turn a blind eye to the activities of radical, dangerous Jihadist elements that crossed the border unimpeded. These militants typically moved into Syria via the Turkish-Syrian border, a route popularly known as the ‘Jihadi Highway’. As the war dragged on much longer than Ankara anticipated, Turkey fell into the trap of sectarianism, and became identified with the Sunni camp. Due to its lack of military, economic, and political reach, the Turkish government could only watch as radical Islamist groups took over and controlled large parts of Syria. Turkey’s inability to respond to Syria’s provocations militarily and its failure to persuade its allies to intervene exposed the great gap between Ankara’s ambitions and its capacities.

NOT ABOUT DEMOCRACY: TURKEY’S LOST ISLAMIST GAMBLE

After 2011, Turkey viewed Islamist parties in Tunisia, Syria, Yemen, Egypt and Libya as its natural allies. It appealed to Saudi Arabia, the US, and the EU for support, arguing that the ascendancy of these parties was a democratic imperative. However, Saudi Arabia, Turkey’s ostensible partner in Syria, viewed the Muslim Brotherhood – which came to power through elections – as an existential threat. At the same time, Turkey’s overt or covert ties to radical Islamist groups in Syria gave rise to serious misgivings in the West. These failures – combined with the government’s reluctance to normalise relations with Israel, despite an apology by Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu for the Mavi Marmara incident that President Obama personally brokered – soured relations with Washington as well.

The desire to see kindred spirits (i.e. Islamist parties) in power undid Turkey’s policy towards Egypt, and throughout the region. Having been exclusively concentrated on helping out the Muslim Brotherhood government, Ankara’s Egypt policy fell apart when that government was ousted in the 2013 military coup. Prime Minister Erdogan’s response to the coup went beyond simple criticism.

The Turkish discourse of sanctifying the will of the people turned into a diatribe against all parties that either kept quiet or actively backed the Sisi regime.

For example, Erdogan said in July 2013 that ‘those who cannot call a coup a coup are supporters of the coup’. No country was spared the abusive language used by Erdogan and his colleagues, with the result being that Turkey found itself cut off from Egyptian affairs, and isolated in the international community.

Yet, it was obvious that Ankara misread the correlation of regional forces at a crossroads moment, including within Turkey itself. Just prior to the Egyptian coup, the Turkish government responded with fury and intense violence to the domestic urban protests triggered by urbanisation plans for Istanbul’s Taksim Gezi Park in June 2013. The prime minister presented this genuine demonstration of frustration and discontent as part of a wider conspiracy, and gave unconditional support to the police that overused pepper gas, killing 8 individuals and blinding 11. As Ankara’s own governance practices undermined the rule of law, Turkey’s democratic credentials were devalued internationally. Under such circumstances, Turkey’s defence of various Brotherhood outfits in the name of majoritarian electoral legitimacy was stripped of credibility.

But not only did Turkey lose the high ground in terms of the democratic image that had been among its major geopolitical assets internationally. Ankara’s choices in Syria and its inability to adjust to changing conditions on the ground also led to an erosion of its geopolitical advantages. By the end of the fourth year of the Syria conflict, Turkey had lost much of its prestige throughout the region as well as among its global allies. Its permissive policies towards Jihadist groups were widely criticised, including by the Vice President of the United States.

Today, Turkey’s once so promising regional standing lies in ruins. Ankara’s main political partners in the region are non-state actors such as Hamas and the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood. Ankara has no ambassadors in Israel, Egypt and Syria.

In the Eastern Mediterranean, two triangular alignments, one between Greece-Israel and Cyprus and the other between Israel, Egypt and Cyprus, threaten Turkey’s core interests. Under immense pressure, Ankara’s main remaining ally, Qatar, has been forced to get in line with other Gulf countries (especially Saudi Arabia). Even in its most promising strategic investment, its close relations with the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq, Turkey’s choices have led it to lose ground to Iran and Ankara’s nemesis, the PKK.

The coup de grace against Turkey’s Middle Eastern policy came in the predominantly Kurdish town of Kobane in Syria, where forces of Daesh (the self-proclaimed ‘Islamic State’) besieged the city. The sudden expansion of Daesh in June 2014 and its takeover of Mosul in Iraq changed the strategic balances in Syria and Iraq. Effectively, the border between the two countries in the predominantly Sunni parts of each country disappeared. Despite warnings, the Turkish government chose not to evacuate its Consulate in Mosul before it was taken over by Daesh. As a result, Daesh took 49 Turkish hostages.

Ultimately the fighters of Kobane were aided by US air strikes, and US pressure finally led Turkey to allow Kurdish Peshmerge forces from Iraq to cross its territory and go fight alongside the defenders of the city, forcing Daesh to withdraw. In addition, Turkey’s Kurdish citizens had relatives in Kobane and wanted to fight there but were prevented from crossing the border, so Ankara’s policy towards Kobane also harmed Turkey’s domestic Kurdish reconciliation process. In sum, Turkey’s failure to respond effectively to the Kobane siege sealed the demise of its ambitions to be a regional power with the capacity to shape the new structure of the Middle East’s tragically collapsed order.

CONCLUSION

The AKP government’s Middle Eastern policies in the wake of the 2011 Arab revolts clashed with much of Turkey’s time-tested traditional geopolitical inclinations. Davutoglu’s preferences, supported by Erdogan, did away with Ankara’s erstwhile pragmatism and let ideological considerations guide policy instead. The behaviour that ensued in recent years, as a result of this imprudent delusion, cost Turkey the one realistic window of opportunity to become a key regional power. Turkey’s thinly veiled geopolitical expansionism has discredited its superficial democracy discourse, which was undone both by Turkey’s domestic record and its tacit support to anti-democratic forces across the region, including as a midwife of Sunni Jihadist radicalisation in Syria and Iraq. Picking up the pieces, the realist tradition of Turkish foreign policy is likely to make a comeback: whatever its governmental rhetoric in the coming years, Turkey will seek to reposition itself along more traditional lines, by the side of its American ally and mending ties with the key regional powers.

About the authors:

Soli Ozel is Lecturer at Kadir Has University and Behlul Ozkan is Assistant Professor at Marmara University.

Source:

This article was published by FRIDE as Policy Brief 200 (PDF).

This Policy Brief belongs to the project ‘Transitions and Geopolitics in the Arab World: links and implications for international actors’, led by FRIDE and HIVOS. We acknowledge the generous support of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway. For further information on this project, please contact: Kawa Hassan, Hivos (k.hassan@ hivos.nl) or Kristina Kausch, FRIDE (kkausch@ fride.org).