Japan’s Quest For A New Normal – Analysis

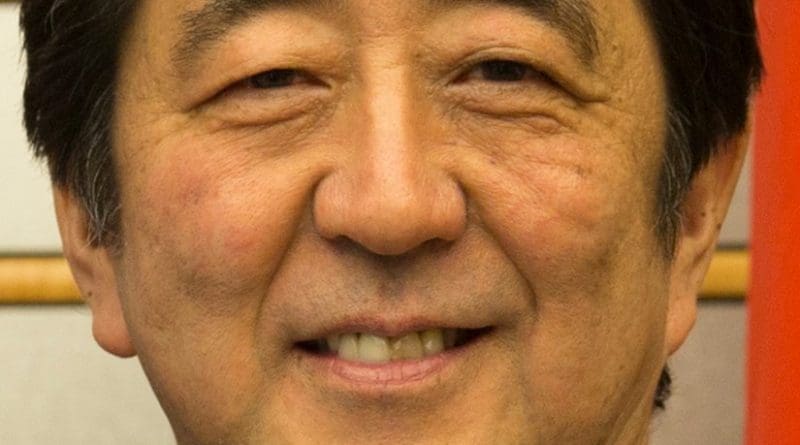

Shinzo Abe’s quest to transform Japan into a ‘normal’ sovereign state is a risky and dubious proposition, warns Samir Tata. What he should be focusing on is becoming a better neighbor – i.e., on resolving Tokyo’s ongoing territorial disputes and improving its relations with Indonesia and North Korea.

By Samir Tata

Japan, under the leadership of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, is on a quest for a new normal. The ultimate objective is to restore Japan to the status of a normal sovereign state that has “the inherent right of individual and collective self defense” as recognized in Article 51 of the United Nations Charter of 1945. Japan remains the only country to have voluntarily renounced this right pursuant to Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution of 1946, drafted under the guidance of the United States.

Abe’s ambition is to amend the Japanese Constitution to effectively repeal Article 9 so that Japan can once again be considered a normal state. Unfortunately the path to achieving this goal risks rekindling aggressive Japanese nationalism by juxtaposing assertive territorial claims to three sets of disputed islands and an ambitious program of military modernization and expansion. It is time then for Tokyo to push the reset button and execute a course correction. A reconfigured Japanese strategy to regain its status as a normal state must incorporate two key elements: (1) resolving territorial disputes, and (2) crafting a “good neighbor” policy that starts with North Korea and Indonesia.

Peace on the Rocks

Currently, Japan’s quest for normalcy risks being wrecked by three sets of disputed islands: the Kuril Islands in the Sea of Okhotsk (occupied by Russia since 1945), the Takeshima/Dokdo Islands in the Sea of Japan (unoccupied but administered by South Korea since 1954), and the Senkaku/Daioyu Islands (unoccupied but administered by Japan since 1971). As a result of these disputes, Japan has been unable to fully normalize relations with Russia, South Korea and China.

Japan and Russia have yet to sign a peace treaty formally ending the Second World War because of the dispute over the Kuril Islands. And while a resolution of the dispute has been on the table since 1956, Japan still refuses bring this matter to a close. It’s time for a change. Indeed, Tokyo can capitalize on the success of signing this treaty by negotiating an oil and gas pipeline deal (bringing Russian oil and gas resources to Japan) that only enhances Japan’s energy security. Moreover, as the Bering Sea becomes navigable year round due to global warming, Japan will be in a favorable position to secure transit rights through Russian waters, significantly reducing shipping time to northwest Europe and northeast America.

Similarly, the dispute over Takeshima/Dokdo Islands in the Sea of Japan remains a major obstacle to closer cooperation between South Korea and Japan. Yet, the chances of Japan ever regaining the islands are nil. Continuing to press its claims has no upside for Tokyo. If anything, it helps to maintain frosty relations between Seoul and Tokyo, encourages further South Korea – China cooperation against Japan and weakens the US effort to counterbalance China. Accordingly, it is in Japan’s interest to unilaterally renounce its claims to Takeshima/Dokdo Islands (which are also claimed by North Korea). Tokyo could couple this renunciation with a reaffirmation of its repentance for its actions during the period Korea was under Japanese rule. Such a move would dramatically transform South Korean-Japanese relations.

Perhaps the single biggest threat to peace in East Asia today is the increasingly strident dispute between Japan and China over the Senkaku/Daioyu Islands, a group of 5 barren rocks in the East China Sea. Washington’s position on the dispute is that it is neutral with respect to the question of sovereignty but recognizes that the islands are under Japanese administration. Accordingly, the Senkaku/Daioyu Islands are covered under the US-Japan Mutual Defense Treaty (1960). In the event of an armed Chinese takeover of the disputed islands, the US would be obligated to take action pursuant to Article V of the treaty, but the nature of its response would be determined independently by the US “in accordance with its constitutional provisions and processes”, and could range from a verbal statement deploring the Chinese action to a military intervention. It is highly unlikely that the US would allow itself to be sucked into war by virtue of this dispute.

The risk Japan faces by escalating its rhetorical assertions of sovereignty over Senkaku/Daioyu is that China responds by initiating a series of intrusions (such as the November 2013 declaration of an Air Defense Identification Zone) that effectively undermine Tokyo’s claims to sole administrative jurisdiction. The end result of this “salami slicing” tactic could be a physical takeover of the islands by the Chinese. Under the present escalatory dynamic, it is Chinese forbearance and strategic patience that determines when and not if the Senkaku/Daioyu Islands revert to Chinese sovereignty. It is clearly in Japan’s interest to step off the current escalatory ladder.

Indeed, Japan has a unique opportunity to create a new dynamic by selling part of the Senkaku/Daioyu Islands to Taiwan (which has asserted its own claims to the islands). In 2013, Japan and Taiwan signed an agreement sharing fishing rights in the waters surrounding the disputed islands. Japan, which purchased three of the five islands from a private Japanese owner in 2012 for about $ 25 million, could now turn around and sell the three islands to Taiwan for the same price, while retaining the present arrangement with respect to fishing. Again, Tokyo could couple this deal with a reaffirmation of its apology to China and Taiwan for the actions of the Japanese Empire against the Chinese people. Since Japan, China, Taiwan and the US agree on the “One China” policy, these three islands will eventually revert to Chinese sovereignty and administration upon Taiwan’s reunification with China. Tokyo will have demonstrated that it has the wisdom to exchange barren rocks for a mutually beneficial peace.

Crafting a “Good Neighbor” Policy

By resolving its territorial disputes with Russia, South Korea and China, Tokyo will have laid the foundation for a mutually beneficial “good neighbor” policy. Japan can leverage its success by normalizing its relationship with North Korea, and establishing a new anchor relationship with Indonesia.

North Korea is the only member state of the United Nations with which Japan has no diplomatic relations. By contrast, Japan normalized its relations with South Korea in 1965. It is high time, therefore, for Tokyo to do the same with the North. Then Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi (Shinzo Abe was then Deputy Cabinet Secretary) took the first step towards rapprochement when he visited Pyongyang on September 17, 2002. At that time, Koizumi apologized for Imperial Japan’s rule over Korea, with Kim Jong-Il apologizing for the abduction of Japanese citizens by North Korean intelligence services in the 1970s.

Unfortunately, further progress on normalization foundered on Japan’s displeasure over what it considered unsatisfactory explanations of the deaths of eight of the abductees. Japan should separate and compartmentalize this issue so that it does not become an obstacle to establishing diplomatic relations with North Korea. Additionally, Japan should unilaterally make a significant down payment on a reparations package to be negotiated with North Korea. As part of this reparations package, Tokyo should propose the establishment of a North Korean special economic zone within which Japanese companies could have assembly and manufacturing facilities, thereby providing North Koreans with badly needed employment opportunities. It will be essential to delink the intermittent six-party talks regarding North Korea’s nuclear weapons program from any bilateral Japan-North Korea discussions with respect to the establishment of diplomatic relations or reparations. Both reparations and diplomatic relations are quintessentially bilateral issues that have no intrinsic relationship to the multilateral discussions on the North Korean nuclear program. Reparations arise from Imperial Japan’s occupation and annexation of Korea.

From both a strategic and economic perspective, it is also vital for Japan to have friendly and mutually beneficial relations with Indonesia. As an island nation with virtually no resources, Japan needs to have secure sea lines of communication (SLOCs) to sustain its trade. The SLOCs linking the western Pacific Ocean to the eastern Indian Ocean have four critical chokepoints – Malacca, Lambok, Sunda and Makassar straits – that pass through Indonesia. Safe passage through these waterways is vitally important to Japan as virtually all of its trade with Australia, South Asia, Middle East, Africa and Europe flows through at least one of these chokepoints. From Tokyo’s perspective, strengthening relations with Jakarta is a necessity and not a choice.

Japan also needs to reduce its reliance on China as a low cost manufacturing base for products that are then exported (primarily to Europe and the United States). Indonesia, an emerging democracy with the largest population in Southeast Asia, can serve as an alternative low cost manufacturing base that will help Japan reduce its economic dependency on China. While Japan already has an important presence in Indonesia, Tokyo’s objective should be to diversify and expand its manufacturing activities in the country so that it becomes the single largest foreign investor and manufacturer in Indonesia. Japan’s economic and maritime security will be enhanced if it can build an anchor relationship with Indonesia.

Germany successfully carved a path to a new normal and so can Japan. Resolving territorial disputes over barren rocks, reaffirming the remorse and repentance for the excesses of Imperial Japan, and forging mutually beneficial political and economic relationships with its neighbors will do more to restore Japan’s role in Asia than assertive nationalism. With a prudent and pragmatic course correction to avoid a setback, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s slogan “Japan is back” can be transformed from rhetoric to reality.

Samir Tata is a foreign policy analyst. He previously served as an intelligence analyst with the National-Geospatial Intelligence Agency, a staff assistant to Senator Dianne Feinstein, and a researcher with Middle East Institute, Atlantic Council and National Defense University.