The West In Crossfire And Crosshairs – OpEd

The West is caught in both the crossfire and crosshairs of an historic internecine war for control of the Islamic world. Historic Arab control of that world in the post-World War I period is challenged by non-Arab powers like Iran and Turkey, and Arab countries that have long been Western allies, like Saudi Arabia and Jordan, are threatened. The West is in a repetitious and futile posture, responding at each turn to one attack after another. An approach to some meaningful strategy may involve taking several steps back, assessing the history and roots of the problems, determining our essential interests and reserving our efforts to achieve objectives consistent with those interests.

Islamic terrorism is creating chaos around the world. Massacres by Palestinian groups in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, notably the murders at the 1972 Munich Olympics, kicked off the modern movement of Sunni terrorism vitally affecting the West. In 1979, Shiite terrorism sprung onto the scene with the Islamic coup in Iran and the establishment of the Islamic Republic. The 444-day seizure of the U.S. Embassy in Teheran was followed by Iran’s export of Shiite Islamic terror, first to Lebanon and later to other parts of the Middle East. Sunni terrorism once again drilled itself into the consciousness of the West with the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center and the massive attacks of September 11, 2001.

Theology defines the difference between Sunni and Shiite–essentially a dispute over the legitimate succession to Muhammad–and the two tendencies are often at odds and sometimes violently so. And the Islamic world includes much more than Sunni and Shia, for example, Sufi, Alevi, Alewite, and other sects treated as heretical by the two mainstream groupings. Within Shia and Sunni there are subgroups that differ, sometimes to the point of warring with each other. Although Sunni and Shia vie for power, they have, however, at times also cooperated in terror operations, such as funding by Iran, the leading apostle of Shiite terror around the world, of Hamas, a Sunni organization. Turkey, with aspirations to recreate a Sunni Ottoman caliphate, along with a Shia world dominated by Iran, would be the grandest of such cooperation.

By now, an alphabet soup of other Islamic terror organizations of both Sunni and Shiite stripes, has come to the fore. These include Boko Haram in Nigeria, ISIS/ISIL/Islamic State in Syria and Iraq, the Houthis in Yemen, the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) in the Philippines, Al-Qaida in the Arabian peninsula ( AQAP) in Yemen, Ansar al Islam and AQI in Iraq, Al-Qaida in the Maghreb (AQIM) in North Africa, the Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade and the Abdallah Azzam Brigades (AAB) in Gaza, Hamas in the West Bank and Gaza, the Haqqani Network (HQN) in Afghanistan and Pakistan , Harakat-Ul Jihad Islami in Pakistan, Hezbollah (Party of God) in Lebanon, Jaish-e-Mohammed (JEM) in Pakistan, Jemmah Ansharut Tauhid (JAT) in Indonesia, Jemaa Islamiyah (JI) in Southeast Asia, and Al-Shabaab in Somalia, to mention a few.

The Ottoman Empire, a Sunni dynasty, established what some historians refer to as the Pax Ottomana, a period of seeming relative economic and social stability in the subjugated provinces of Asia Minor, the Middle East, the Balkans, North Africa, and the Caucasus in the 16th and 17th centuries. In roughly the same period, a series of Shiite dynasties ruled in Persia, beginning with the Safavid in 1501. Although the Muslim conquest of Persia in the 7th century was spearheaded by Sunni Arabs, the Safavids forcibly converted the population to Shiism beginning in the early 16th century, and it became fully established in Persia by the early 17th century.

And the Shia have been largely limited to Iran until the 1979 revolution led to an aggressive, expansionism vying for control in Sunni countries.

On the international stage, Sunni Muslims, even after they suffered a series of territorial rollbacks after their defeat at the Battle of Vienna in 1683, appeared to be the more dynamic force. In what turned out to be its final years, the Ottoman Empire–under the influence of the revolutionary movement the “Young Turks”– entered World War I on the side of Germany in 1914, and at the same time declared a jihad– holy war–on Germany’s opponents, Britain, France, and Russia. It was during this period that the most severe stage of the genocide of Armenian Christians also took place.

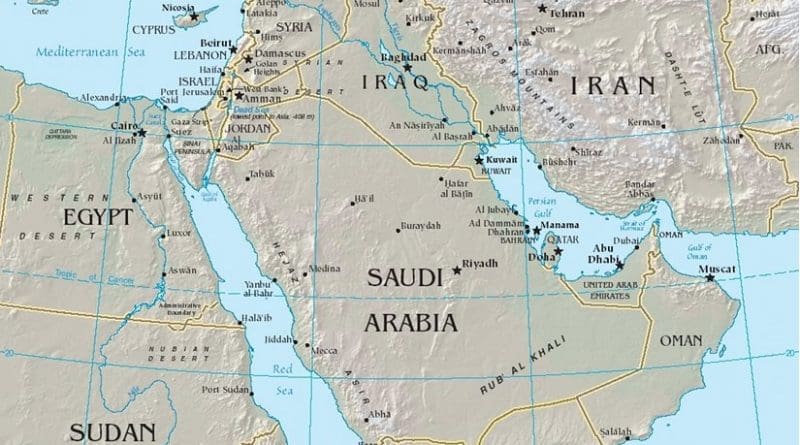

After World War I and the defeat of the Sunni Ottoman empire, the League of Nations sought to avoid chaos and religious wars established mandates in the predominately Arab Middle Eastern territories of the former Ottoman Empire under France (Syria and Lebanon) and Great Britain (Mesopotamia and Palestine). From these agreements emerged new nation-states: Syria, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Iraq. The mandate for Palestine remained until the British withdrawal in 1948, and the declaration of the State of Israel.

Lebanon–which became independent in 1943, while its mandate-holder, France, was occupied by Nazi Germany–sought after the war to establish a system based on quotas for their major religious groups. Syria also became a republic. A series of coups led to the seizure of power by the Ba’ath Party, an Arab nationalist and nominally socialist movement, another branch of which also took over in Iraq in1963. Under the British mandate, branches of the Sunni Hashemite dynasty were established as royal houses after World War I in Iraq and Jordan.

Sunnis retained the dominant position in the Arab world in the interwar period, and Shia and many other Islamic sects in the region were given short shrift by the new regimes. This semblance of order lasted for decades, but by the late 1970’s was frayed and fractured. Today it is in shambles, with conflicts on many fronts.

Foremost among these disruptive forces was the seizure of power in Iran in 1979 of a radical Shia movement, giving this Islamic sect a platform with a degree of influence not seen in centuries. It has driven to dominate not only its own country, but also Iraq, with its majority Shiite population but historically under Sunni rule; Lebanon, through its proxy terrorist group Hezbollah; Syria, though its ally Hafez al-Assad; and most recently Yemen, through the Houthis. In Iraq, for example, Iran for all practical purposes controls the oil- rich Basra region. Shiites now have at least partial control of both straits bordering the Arabian peninsula, potentially affecting key oil routes in the Persian Gulf and world trade routes thought the Suez Canal.

Iran has allied with countries and non-state entities as far away as Argentina. It has been effectively at war with the United States–the “Great Satan”–since the 1979 takeover, and, of course has long been pushing to acquire–if it hasn’t already done so– nuclear weapons.

The West in general, and the U.S. in particular, seems to be in a kind of zugzwang–the chess term for a position in which any move will make the player worse off. For the West to fight the Islamic State (IS), a Sunni rival, redounds to Iran’s benefit, while seeking advantage over Iran, to forestall its gaining atomic status, for instance, may further empower IS and other Sunni terrorist states or organizations. There are some “win-win” moves for the U.S.; support for Israel, which is on the front lines against both Sunni and Shiite enemies, and which is the nation under the most dire threat from Iran, is an example.

In the past, control could be maintained by agreement of the major powers to divide the warring territories, as happened for a time after World War I. Strong transnational powers, like the Soviet and Ottoman Empires, and tyrannical states, like Iraq under Saddam Hussein and Yugoslavia under Tito, could rule by suppressing religious differences. The results were not necessarily lasting and were certainly not pretty.

In any event, such “solutions” are not now possible. All the West can do is decide who its allies are at any given moment–in this region they will not be forever–and support as points by which to navigate the terrain. Such Middle East allies now include Saudi Arabia, Jordan, the Emirates, Kuwait, Israel, Egypt, and Iraqi Kurdistan.

On January 1, speaking to clerics in Cairo, Egyptian President al-Sisi, noting that the “corpus of texts and ideas that we have sacralized over the years . . . is antagonizing the entire world,” called for a “religious revolution.” “The entire world,” he declared, “is waiting ” for the imams’ “next move,” lest the entire Islamic world become “a source of anxiety, danger, killing and destruction for the rest of the world. Impossible!” “All this that I am telling you, you cannot feel it if you remain trapped within this mindset. You need to step outside of yourselves to be able to observe it and reflect on it from a more enlightened perspective.” If such sentiments are real, those who undertake this task deserve support.

Barry A. Fisher, is former Chairs Religion and Law Committee World Jurist Assoc., ABA Religion Subcommittee, counsel to Kurdish groups, and has worked on religion issues many countries from Argentina and Japan to Russia and elsewhere, including religion cases at the U.S. Supreme Court and throughout country.