Limits Of Political Development In Maoist Badlands – OpEd

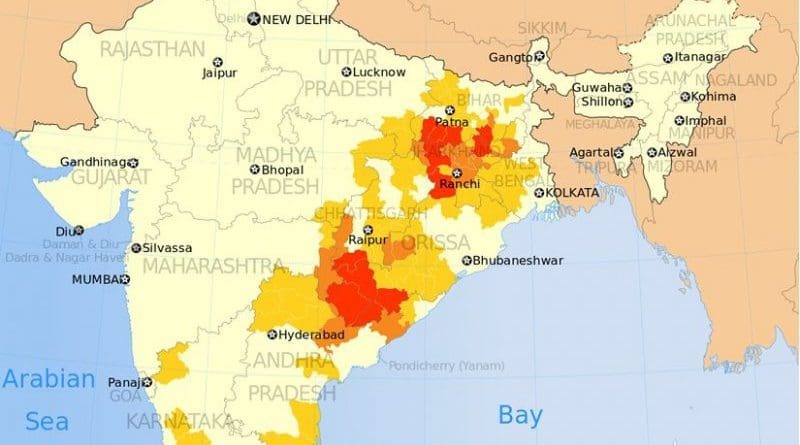

It is ironic that perimeters of the venue, used by Union Rural Development Minister Jairam Ramesh to address a public meeting in Odisha’s Malkangiri district on May 28 during which he belittled the role of the security forces in providing a solution to the Maoist problem, had to be first sanitised and protected by the same forces. While the minister did try to score a brownie point by spending a night in Odisha’s worst Maoist-affected district, the extremists too managed to send an equally forceful message reiterating their area domination. A day before Ramesh’s arrival, Maoists carried out an attack on the forces in the district, injuring three personnel. The minister’s proposed tour to interior areas had to be cancelled in view of the security threat. New Delhi’s current anti-Maoist approach continues to amuse, to say the least.

Since his taking charge of the rural development ministry, Ramesh has managed to launch a parallel strategy to fight the extremists, which sometimes runs in conjunction with the home ministry’s broad plan and sometimes in contravention. There is a surge in the resources available for the Maoist-affected districts under both the Integrated Action Plan (IAP) and also special action plans. Notwithstanding the below par records of the state governments in spending the IAP funds in the past years, Ramesh says that the district collectors and the village panchayats can now become the agents of change.

Many would have missed the subtle modification in the approach of the rural development ministry under Ramesh, elaborated for the first time in his October 11, 2011, Sardar Patel Memorial Lecture. Ramesh eloquently outlined a “two-track approach”, calling for dealing with the Maoist leadership and revamping of administration and governance in tribal areas. Over the next months, however, this two-track approach not only was expanded to a three-track strategy, called the “3Ps”, it involved some tactical prioritisation as well. The new addition is the “intensification of political activities” in the Maoist belt, which Ramesh believes should be the first step before the role of the people and the police/para-military. On May 28, Ramesh said in Malkangiri: “Political intervention is the need of the hour to eliminate Left wing extremism. Political parties must play a big role to deal with Naxal menace… security forces alone cannot fight the menace.”

The critique of the development approach is not a commentary on the sincerity, or the lack of it, of the rural development ministry. What is being argued here is that this alternate approach, both in its initial form and in its expanded version, is based on some grave errors of judgment. It is necessary to test few of these erroneous assumptions against hard realities.

First, any principled opposition to the development strategy would have been sacrilege had the writ of the collectors and panchayats been running over the areas Ramesh wants to develop. The hard reality points to the contrary. The recent and past abductions of the district collectors and panchayat members by Maoists and how that effectively curtails the development activities need no elaboration.

Second, the minister’s advocacy of an enhanced role for the political parties in the tribal belts appears to have been based on the widening influence of the Trinamool Congress (TMC) in the previously Maoist-affected Jangal Mahal area in West Bengal. The reality is that the TMC’s surge was a follow-up to the Maoist decimation, not a precursor. It further needs mention that Jhina Hikaka, the Member of Odisha Legislative Assembly who was abducted by the Maoists and was released on the condition that he would resign from the Assembly, now cools his heels in a protected house in state capital Bhubaneswar. To prod the likes of Hikaka to start being politically active in the Maoist-affected Malkangiri is bound to be a failed venture.

Third, the leeway Ramesh continues to receive to carve out his own approach has mostly to do with the failure of the grand-scale security force operations against the extremists which received some serious setbacks, thereby leading many to conclude that there is indeed no military solution to the Maoist problem. It is important, however, to reiterate that a badly planned security operation had suffered a setback, not the force-centric approach per se. The past counter-insurgency successes India has had in Mizoram, Punjab, Tripura and Andhra Pradesh are predominantly security force-centric, where development either followed the forces or went along with them.

Whether the political leadership is honest about developing a region which has been cleared of Maoist presence is a different question. And it is in that sphere that Ramesh has a lot to do.

This article appeared in Indian Express and is reprinted with permission