Why Philosophy? Reflections On Fides Et Ratio – OpEd

It never has to be faith versus reason. Centuries of Christian philosophical and scientific inquiry attest to this.

By Sarah Negri

“Faith and reason are like two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth; and God has placed in the human heart a desire to know the truth.”

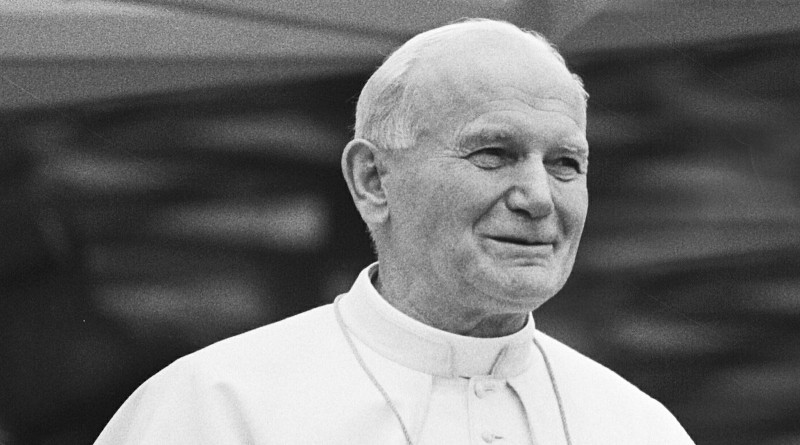

Twenty-five years ago today, Pope John Paul II (JPII) opened his 13th papal encyclical, Fides et Ratio, with these profound, beautiful, and now familiar words. The missive launches from there into an extensive exploration of the relationship between faith and reason, and in particular the relationship between theology and philosophy. On the anniversary of its release, it’s worth reflecting on this rich document and its treatment of themes still relevant to our spiritual and intellectual life today.

The supposed antagonism between faith and reason has occupied a great deal of the thought-space of philosophers, theologians, scientists, clergy, and ordinary Christians throughout the centuries, and contemporary interest in it has not flagged. In today’s philosophical arena, religious epistemologists such as Alvin Plantinga and Lara Buchakwrestle with questions regarding how Christian faith might be compatible with the proper use of our reason. It makes sense why this matters: both faith and reason have to do with belief-forming processes, ways of coming to knowledge about the world, yet superficially approached they often seem to be in conflict. Indeed, many view religion and reason as diametrically opposed to each other. If, however, they are irreconcilable, which should we take as our guiding light when trying to answer the fundamental questions of our existence?

Fides et Ratio (FR) is a valuable contribution to this discussion, offering an ecclesiastical, theological, and philosophical perspective from a unique source of authority. Past church documents had highlighted the connection of faith to reason in various capacities (Vatican I’s Dei Filius in 1870, Leo XIII’s Aeterni Patris in 1879, Vatican II’s Dei Verbum in 1965, and John Paul II’s own Veritatis Splendor in 1993), but FR’s appearance in 1998 was an attempt to provide a new, comprehensive, and timely response to certain trends John Paul II saw in the beliefs and behaviors of the Church, the world, and the academy. First, he emphasizes the need for a renewed interest in asking questions of ultimate meaning amid the technological advances of the modern age. He also wishes to counteract the “widespread distrust of the human being’s great capacity for knowledge” manifested in intellectual despair and desires to restore a metaphysical focus to philosophical inquiry to recover the idea of truth as correspondence to being. Finally, he wants to give the Church and her ministers philosophical tools so they can witness to the truth as known by reason and revelation, both in the teachings of the bishops and in the formation of new priests.

JPII’s observations and exhortations in FR still have relevance for Christians seeking to integrate their faith with their rational capacities as human beings. They provide material to contemplate the delicate interplay between divinely revealed truth and truth attained through human reason, an interplay we experience every day but often have trouble articulating. Most important, they highlight the perennial need for the ongoing study of philosophy by believers for the crucial assistance it provides in the search for truth. JPII especially stresses the value of philosophy because it is “the mirror which reflects the culture of a people,” acting as a sort of weathervane by which we can determine the relevant beliefs of groups and populations.

The most prominent themes of the document are quite simple to state, yet many pages are devoted to their exposition. The first is that truth is one. JPII reiterates this point over and over in his insistence that because they both have God as their source and are oriented toward the truth, faith and reason will never truly conflict. Different types of knowledge based on faith and reason may appear at times to contradict one another, but upon further scrutiny there will never be a lasting divergence. Nevertheless, it is appropriate that the realms of reason and faith pursue truth in distinct ways; therefore, “the truth attained by philosophy and the truth of Revelation are neither identical nor mutually exclusive.”

A second emphasis of FR is that we can know the truth. This strong affirmation of our capacity for knowledge is meant to combat the aforementioned intellectual despair that can arise from surveying the sea of conflicting views, now extensively available in our digital age. Encountering so many contrary opinions and worldviews can make one doubt whether it is possible to find truth at all. JPII asserts sed contra that with the assistance of both divine revelation, accessible by faith, and the powers of natural reason, we can arrive at an accurate understanding of the world. The important thing is to keep these spheres in proper balance, neither excluding revelation as mere dogmatism nor downplaying reason as intrinsically unreliable. More will be said on their proper relationship later.

Closely linked to this is a third emphasis in FR, that we not only can know the truth but that we deeply desire to know it. Drawing from Aristotle’s famous observation that “all men by nature desire to know,” JPII links this natural desire for knowledge with the dignity of the human person. In their rationality, human beings image divine wisdom, and our innate drive for knowledge and understanding, if kept within the bounds outlined for it by God, is a gift from him and leads them back to him. JPII affirms this desire in a paraphrase of Proverbs 25:2: “In God there lies the origin of all things, in him is found the fullness of the mystery, and in this his glory consists; to men and women there falls the task of exploring truth with their reason, and in this there nobility consists.” Our profound yearning to know the truth is a good thing, something to be encouraged, because it is ultimately fulfilled in God, the source of all truth.

A significant feature of JPII’s analysis is the foundation of certainty that faith provides to reason. This certainty of faith is grounded in God as the guarantor of revealed truth and a unique, interpersonal trust in his authority; thus, faith enjoys a certain primacy over reason as a manner of arriving at truth. However, this primacy of faith does not usurp reason’s autonomy as some might complain; rather, it provides “valid points of reference” to keep reason from going astray on its journey, as well as sublime insights from revealed truth that reason would be unable to grasp on its own. This frees reason to perform its role to the fullness of its capacity. Faith is not the enemy but “the convinced and convincing advocate of reason.”

The other major emphasis of FR is its unique focus on the role of philosophy in the search for truth. JPII lays out the long history of philosophy and its interaction with theology in which he discusses the influence of philosophy on culture, the preeminence of certain philosophers such as Thomas Aquinas in the development of philosophical thought, and a number of philosophical pitfalls the person of faith must avoid. Outlining the crucial role philosophy plays in evangelization and the development of theology, he pleads for a resurgence in specific areas, such as philosophy of language, ethics, and especially metaphysics. His words have special resonance for Christian philosophers, underscoring the necessity of their profession and reminding them of the service they can offer the Church through the full utilization of their intellectual gifts.

Fides et Ratio is required reading for anyone serious about understanding the interplay of knowledge, belief, divine revelation, and rational inquiry, and also for anyone looking to understand the importance of philosophy both in the search for truth and as a support to theology. In addition, it is a beautiful document to read and reflect upon for any believer, especially those academically inclined. Twenty-five years later, the issues prompting its release—the pursuit of technological advances in academia over answers to ultimate questions, skepticism and despair of reason’s capabilities, poor theological formation and intellectually informed evangelization—seem not to have dissipated but in some parts of the world to have grown even stronger. John Paul II’s clarion call for a forceful response from the Church is worth returning to.

About the author: Sarah Negri is a graduate student in philosophy at Baylor University.

Source: This article was published by the Acton Institute