French Academician H. Carrère d’Encausse And What Is Most Important In Kazakhstan’s Power Struggles – Analysis

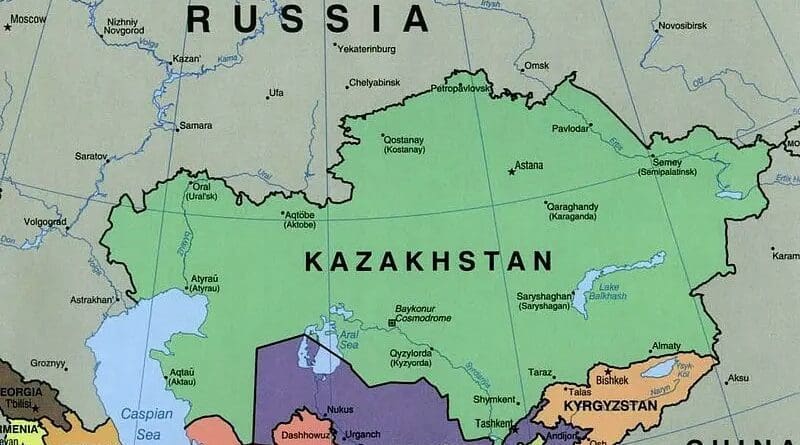

Recently, the Russian Nezavisimaya Gazeta, in an article entitled ‘The biggest risk for Kazakhstan is the loss of sovereignty’, quoted Kazakh Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Murat Nurtleu as having said that three issues in Central Asia, which needed special treatment, were water and environment, border disputes and the situation in Afghanistan. There, it also cited the following statement by Alexander Kobrinsky, a prominent Russian scholar, and director of the Agency for Ethno-National Strategies: “The multi-vector approach which Kazakhstan adheres to is a path to a coup d’état. Reliance on multi-vector policy will lead power and society to disaster. In today’s world, you need to make a choice. Kazakhstan needs not reform, but political and economic development which implies sovereignty”.

The above-quoted opinions related to problems and prospects of the situation in Central Asia, including in Kazakhstan, represent schematic visions of the topic, which are quite characteristic for politicians in Kazakhstan, on the one side, and political experts in Russia, on the other.

But there is one thing which is left outside the field of view when they consider the matter. This is a question of how the ruling regimes in Central Asia fit into the twenty-first century geopolitical and geo-economic reality and match the current level of development of social consciousness in their countries. According to some outside observers, everywhere in the region except maybe in Kyrgyztan, they bring to mind what had been in this part of the world before it ‘was annexed’ by the Russian empire.

Here’s how Hamid Golpira, an Iranian journalist and author, in his article entitled ‘Khans of Central Asia’ and published by the Tehran Times newspaper almost a decade and a half ago, described the position of the region in the post-Soviet period and the authoritarian regimes of Central Asia which had been formed after the dissolution of the USSR: “Central Asia is a key region of the globe, since it sits atop vast reserves of oil and gas and is at the crossroads of Asia and Europe. It will also be the main link in two major transport routes which are taking shape, the North-South Corridor between South Asia and Russia, and the New Silk Road, which is meant to be a recreation of the old trade route that ran from China to West Asia. When the Central Asian states…gained independence after the collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991, former communist party officials took charge, and the authoritarian systems they created strongly resemble the former khanates”. What he didn’t mention then is what those Central Asian khan regimes were like back in the XIX century, before the arrival of the Russians.

Here, before proceeding to consider the matter directly, it is necessary to shed some light on its prehistory. The specificity of the norms in the Central Asian political tradition that goes back thousands of years to the nomadic past is such that for at least a thousand years, the rulers have come to power and kept it (at first, in any case) relying primarily on their own clans and/or tribes.

This was the case in the 10th century, when the Kayi tribe, an Oghuz Turkic people and a sub-branch of the Bozok tribal federation, established the Ghaznavid empire, which came to encompass Afghanistan, Iran, and the Punjab. That also was the case in the 11th century, when people of the Qynyq tribe, a branch of Oghuz Turks, founded the Seljuk Empire, which, at the time of its greatest extent, was controlling a vast area, stretching from western Anatolia and the Levant in the west to the Hindu Kush in the east, and from Central Asia in the north to the Persian Gulf in the south. In later times, the same Kayi tribe established the Ottoman beylik (from which grew the Ottoman empire) in Asia Minor, and the Qizilbash tribal confederation contributed to the foundation and rise of the Safavid Empire in Iran.

Of course, not every tribe or even tribal confederation from Central Asia could lay claim to imposing their power on whole countries. But achieving that kind of scenario has seemingly represented a model of success for any nomadic group initially originating from Inner Asia. In Kazakh, there still is a saying “It is better to be a regular man in your own homeland than to be a sultan in a foreign country”, reminding of those days. It tells that one should appreciate his homeland. But there also is a mention in there about being ‘a sultan in a foreign country’ as an alternative to remaining at home.

And now about what the ruling regimes in Central Asia looked like right before the arrival of the Russians. In the region, the political tradition of taking and maintaining power through reliance on a certain tribal group remained current through the second half of the 19th century in the Kokand Khanate (founded by the dynasty of the Ming tribe) and to the beginning of the 20th century in the Emirate of Bukhara (which was ruled by the dynasty of the Mangit tribe) and in the Khiva Khanate (which was under the rule of the dynasty of the Konyrat tribe).

With the advent of Soviet power that kind of practice was interrupted. But the new generation of strongmen sort of resumed it in Central Asia following the collapse of the USSR. There is perhaps nothing surprising about it. In the post-Soviet period, there have been apparently no particular obstacles to resumption of the Central Asian political tradition of getting and maintaining power through reliance on a certain tribal group, as the time gap proved to be very short by historical standards.

Anyway, there is a strong impression that it got a new lease on life right after the collapse of the USSR in Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan. If to pay attention to the results presumably related to its revival in these three republics, the following can be seen.

Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan entered a period of state independence being under the rule of the leaders of the respective republican communist parties nominated and approved by the Kremlin. Under the changed political and social conditions, those heads of the local communist party organizations became presidents. And the clans, of which they are representatives, have invariably held power in these two Central Asian states all these years. The first of these has been and is being headed by the elites of the Teke tribe, the latter by those of the Senior (Southern) zhuz.

In Kyrgyzstan, there was a dual power shortly before the collapse of the Soviet Union represented by the first democratically elected president, Askar Akayev, and the last two leaders of the Republican Communist Party, Absamat Masaliyev and Dzhumgalbek Amanbayev, nominated and approved by the Kremlin. And, this is perhaps why Kyrgyzstan hadn’t a situation, in which a certain clan group could have secured its monopoly on power. Be that as it may, in that Central Asian country, unlike in Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan, there is no clear predominance of one traditional group community over all others. This is why it can be believed that the rivalry for the control of power in Kyrgyzstan can be quite fierce and intense at times. Whereas in Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan, the ruling clan groups have so strongly rallied their forces and strengthened their own leading positions in the state administration system during the post-Soviet period that there now is almost no possibility of challenging them.

Returning to the subject of Kazakhstan, we here must make a small note. The division of the Kazakhs into tribes is still being preserved and continues to play an important role in the political, economic, and social life in Kazakhstan. At the national level, the focus may be placed, first of all, on their dividedness into three tribal groups: the Senior zhuz, the Middle zhuz and the Junior zhuz.

The Russian political elites, which have a broad experience in acting as a kind of supervisory power instance for dealing with internal contradictions between the Kazakh clan/tribal groups, are clearly very knowledgeable about the matter. Certainly, the times are different now. Yet the Kremlin is obviously not averse to going on with the practice of exploiting this factor as a unique means of applying pressure on the Kazakh ruling regime with the aim to induce Astana to follow in the wake of Russian interests, a means that nobody else has in the club of great powers. In other words, Moscow has its trump cards regarding Kazakhstan that the Americans and their allies, as well as the Chinese, do not have. And understandably, the Russian side is not in a hurry to reveal them.

High-ranking official representatives of Moscow have never been seen raising the topic of political tribalism in Kazakhstan. Should the Russian authorities have a reason to be unhappy with Astana and hence the need to exert – through exploiting such a factor – pressure on it to get it to do what the Russian side wants they are making use of Russia’s media, taking advantage of the Russian television’s and the internet resources’ actually unchallenged dominance on the Kazakhstani information field. Here’s the thing. When there is an ambiguous situation in relations between Moscow and Astana, Russian journalists, political analysts, and even politicians who don’t occupy official positions in the executive branch simply begin to incite the Middle zhuz and the Junior zhuz Kazakhs against the Senior zhuz elites who embody the ruling regime in Kazakhstan. These demarches should probably be seen as a kind of warning to Astana by Moscow. That method seems to be working without fail. Whatever the developments, Astana never goes to the exacerbation of relations with Moscow. Anyway, over the last thirty or more years, the Kazakh ruling regime never once allowed itself to publicly criticize the Russian government, let alone Russia’s president.

This appears to be utterly paradoxical unless one takes into account the Kremlin’s being pretty clear in supporting the current Kazakh ruling regime in the Kazakhstani domestic political context. It is difficult to explain all of that in any other way. Our guess is that obvious signs of the consistently favorable attitude by Moscow towards the actual Kazakh regime are exactly what contributed significantly to the stability of its rule for many years now. That seems to be what is mostly needed by the official Astana from the Russian leadership. The flip side of the coin is preserving the Senior zhuz elites’ monopoly of power in Kazakhstan. When the Russian authors say that ‘the information environment [in the Central Asian country] now is quite friendly to the authorities of Kazakhstan solely thanks to the support of Moscow, which protects the republican elites’, what they mean, among other things, is apparently that the Russian side is the one who controls the public discussions of the topic of political tribalism in Kazakhstan and does prevent them from going bigger.

As for the matter of what is the degree to which the West’s political and public circles are aware of this specific aspect of Kazakh political culture and life, this remains an open question. Even less certain is the West’s ability to more or less successfully compete with Russia for influence in Kazakhstan with little or no regard for that factor. This is all perhaps worth regretting, especially given the fact that it was Western scholars who were the first to note at the academic level that the factor of belonging to a particular tribe or tribal group had a crucial role to play when the Kazakhs were determining their political choices.

Particularly noteworthy among these was French Academician Hélène Carrère d’Encausse, who introduced to science the idea about Kazakh political tribalism back in the mid-1960s (Central Asia, a century of Russian rule, New York, Columbia University Press, 1967). She then was referring to what was happening in Kazakhstan a century ago. Here is what the Kazakh ex-deputy-prime minister, Galym Abilsiitov, says about what’s the situation with that nowadays: “In Kazakhstan, the only form of the division [of society] that runs through force fields are the zhuzes [the tribal groups]; only on this basis – the fact of belonging to one or another zhuz – people identify each other”.

This means that the phenomenon, which was once mainly local in nature, has now gained nationwide relevance, as may be seen from the following independent (or impartial) testimony. Here is what French newspaper Le Figaro’s François Hauter wrote in this regard: “For all Kazakhs, political life boils down exclusively to the internal struggles of hordes [zhuzes] and clans [tribes]. “The transfer of the capital to the city of Astana neutralized the aggressive tendencies of the Middle zhuz towards the Senior one, because Astana is located on the territory of the Middle horde”, explains a keen observer” (‘Guerre de clan dans les steppes kazakhes’, Le Figaro, mardi 21 septembre 2004, p. 4).

The wider Western public, being aware of the talk going on in Russia about opening a second front in the Central Asian direction, and almost unequivocally assuming that Russia can intervene in Kazakhstan’s internal affairs just under the pretext of protecting the Russian minority in the country, risks being misled. A scenario in which Putin would commit aggression against Kazakhstan motivated by the problems of the Russian-speaking population and the ‘Russian issue’ in this nation was unlikely before and is much less real now, in conditions where Russia is turning east.

But this is unlikely to mean that Moscow would thenceforth be refraining from active intervention in Kazakhstan’s internal affairs. For this, the Kremlin may prefer to resort to using the factor described by, say, François Hauter in his Le Figaro article. Sooner or later, Moscow could be tempted to start pitting different groups of Kazakhs against each other, taking advantage of the Russian television’s and the internet resources’ actually unchallenged dominance in the Kazakhstani information field.

It is worth noting here that some Russian outlets are already carrying out such activities. Here and here and here are just some pieces of evidence. Should those who are behind such activities manage to bring about an internal Kazakh split and thus justify the need for Russia’s intervention in Kazakhstan as an impartial force, neither the West, nor China would see any serious pretext for accusing Moscow of aggression against its neighbor.