What Fallout From Russian Anti-Satellite Test Means For Space – Analysis

By RFE RL

By Mike Eckel*

In December 2020, pilots were warned by the Russian authorities: Stay away from a vast swath of airspace in the Laptev Sea off Russia’s northern coast during the second week of the month. The reason? “Hazardous operations, rocket launching.”

A few days after the warning was issued, U.S. officials described what happened — a Russian test of an anti-satellite missile weapon — and what might happen next. “If this weapon is tested on an actual satellite…it will cause a large debris field that could endanger commercial satellites and irrevocably pollute the space domain.”

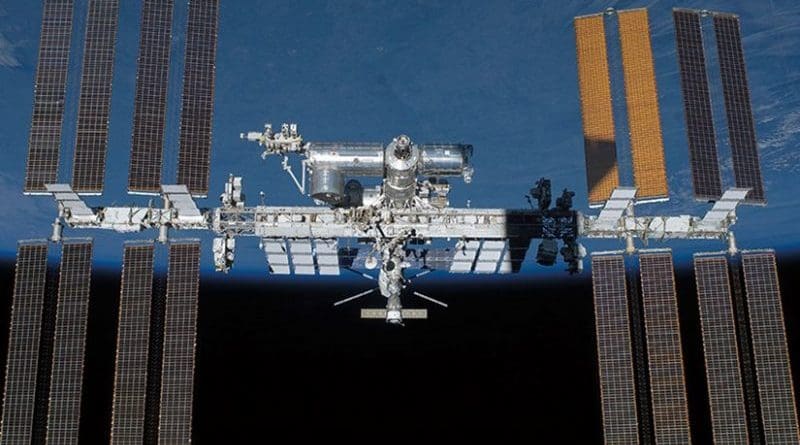

Eleven months later, that exact thing occurred: A cloud of deadly debris whipping around the Earth at a dangerous altitude, prompting NASA to wake the sleeping, seven-member, multinational crew of the International Space Station (ISS) and send them scrambling for refuge for two hours in docked spacecraft docked at the orbiting outpost.

The consensus among a growing number of experts is that the cause of the November 15 incident was a Russian test of a weapon intended to knock out hostile satellites.

What resulted was not only a scare for the space station crew, but also unusually angry rhetoric from Washington, which accused Russia of “reckless” and “dangerous” and “irresponsible” behavior.

“My take is that this is a very bizarre situation, in the sense that with any reasonable decision-making system, I just don’t see how this type of thing would happen,” said Pavel Podvig, a Geneva-based researcher and author of a well-regarded blog on Russian military activity.

As many as 1,500 larger fragments were kicked out from the destroyed satellite, U.S. officials said, something researchers said was likely only the tip of the iceberg. “There are a lot of things people could disagree on, but there’s one thing that everyone agrees on: You should not create debris, especially at a higher altitude, putting astronauts in danger,” Podvig told RFE/RL.

“This is not the Russians first rodeo with” anti-satellite tests, said Brian Weeden, a former U.S. Air Force officer who now heads the Secure World Foundation, a Washington think tank. “I would tend to hope they would know what would happen with the debris cloud after such a test.”

In Moscow, more than 24 hours after the station’s crew was first sent scrambling, there was no immediate response or confirmation that such a test had been conducted, or that a debris cloud had been caused in the first place.

‘Reckless And Dangerous’

Russia’s space agency, Roskosmos, issued the first of two statements on November 15, several hours after the reported incident, saying that the ISS had been forced to shift its orbit but was now operating normally in a “green zone.”

A second statement, on November 16, mentioned Russia’s longtime cooperation in space with other countries: “For us, the main priority has been and remains to ensure the unconditional safety of the crew,” the agency said.

Neither statement made any mention of any missile test or debris cloud.

The U.S. space agency, however, which has worked closely with Roskosmos for years, was quick, and unconstrained, in its annoyance.

“With its long and storied history in human spaceflight, it is unthinkable that Russia would endanger not only the American and international partner astronauts on the ISS, but also their own cosmonauts,” NASA administrator Bill Nelson said in a statement. “Their actions are reckless and dangerous, threatening as well the Chinese space station and the taikonauts on board.”

NASA’s rhetoric echoed that of the U.S. secretary of state, Antony Blinken, who called the test “reckless” and said the debris “risks astronauts’ lives, the integrity of the International Space Station, and the interests of all nations.”

The Russian Defense Ministry later confirmed there had been what it called a “successful test” that destroyed a defunct satellite — a Soviet-era military radio-surveillance satellite called Tselina that was put into orbit in 1987. The ministry denied that fragments that resulted from the test posed any danger to other satellites or the space station.

“It is hypocrisy to say that the Russian Federation creates risks for the peaceful use of outer space,” Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said. “There are no facts.”

Changes In Altitudes, Changes In Attitudes

Both the Soviet Union and the United States had formidable civilian space programs. Think Sputnik or Apollo. Both had formidable military space programs as well, and the two have engaged in a slow-motion space weapons race, testing anti-satellite weapons, researching things like lasers, or radio-wave blasts, or outright kinetic explosions like from missiles. Some of the efforts focused on destroying ballistic missiles from space, rather than satellites. The countries conducted at least 50 anti-satellite tests during the Cold War, according to Weeden.

In 1967, Moscow and Washington signed the Outer Space Treaty, which bans orbiting nuclear weapons while also stating that all countries are free to use space for peaceful purposes as long as they do so in accordance with international law. The treaty, however, does not prohibit deliberate attacks on satellites or prevent anti-satellite-weapons tests.

The two countries also began cooperating on civilian space programs, an effort that has continued despite politics and even the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In the 1980s, the U.S. military tested jet-launched missiles that would target orbiting satellites, but the result was clouds of shrapnel and various sized metal objects that ended up catapulting around the planet at potentially lethal speeds. Congress ended up canceling the program.

In 2007, China used a ground-launched missile to send a homing vehicle to destroy an aging weather satellite at an altitude of around 865 kilometers. According to the Union of Concerned Scientists, a U.S. nongovernmental organization, the destruction of the satellite “created more persistent debris than any other event in space.”

A year later, the U.S. military used its sea-based Aegis missile-defense system — which has drawn complaints from Moscow for years — to destroy a nonoperational U.S. satellite. In that case, the satellite destruction occurred at a lower altitude, and the debris that was sprayed out only lasted in orbit for a short time.

In 2019, India surprised the global space community by conducting its own anti-satellite test. That object was hit, and destroyed, at around 282 kilometers above the Earth, in a way that experts said minimized the longevity or breadth of an orbiting debris cloud.

Still, according to Marco Langbroek, a Dutch researcher who tracks spy satellites and military tests and is affiliated with Leiden University in the Netherlands, it took two years for nearly all of the Indian debris to leave orbit.

Nudol

Sometime in the early 2010s, weapons experts say, Russia began development of an anti-satellite system called PL-19 Nudol. The system is known as a “direct-ascent anti-satellite weapon” — essentially a missile launched from the ground at an orbiting object.

According to Podvig and other researchers who track such launches, Russia has conducted 11 tests of the Nudol system since 2014; some were just tests of the rocket engines or navigational systems; they weren’t vaulted into space. Some were from fixed launch pads, like the Plesetsk Cosmodrome, a major facility in the northern Arkhangelsk region used for civilian and military launches. At least one was from one of Russia’s well-known mobile truck launchers.

On December 15, 2020, the Russian authorities announced a NOTAM — an acronym for an internationally recognized announcement called a Notice To Airmen — for a section of the Laptev Sea.

On December 16, an Angara rocket was launched from Plesetsk in the direction of the Laptev Sea, to the northeast. Later that same day, U.S. Space Command issued a statement saying that a “direct-ascent anti-satellite” missile had been used:

“Russia’s persistent testing of these systems demonstrates threats to U.S. and allied space systems are rapidly advancing,” General James Dickinson said. “The United States is concerned by Russia’s continued development and deployment of several types of ground-based and space-based ASAT weapons.”

“If this weapon is tested on an actual satellite or used operationally, it will cause a large debris field that could endanger commercial satellites and irrevocably pollute the space domain,” he said.

In March 2021, less than two months after President Joe Biden was inaugurated, the United States and Russia convened an unusual working group for discussions on “space security.”

It was unusual, Podvig said, because “space security” is an issue that isn’t usually a top or urgent priority. Plus, the White House had publicly indicated it had other major issues to hammer out with Moscow: arms control and cyberattacks, first and foremost.

In May 2021, Russian officials issued another NOTAM for the same region off the Arctic Coast: a missile launch from Plesetsk that observers said appeared to be another test of the Nudol system. However, there was never any public confirmation of a launch.

‘A Denial That Has No Value’

The angry rhetoric from NASA contrasts with the diplomatic and restrained tone normally heard in public discussions of relations with Roskosmos.

The two agencies cooperate closely in maintenance and upkeep of the ISS. For most of the 2010s, after the Americans grounded their shuttle fleet, Russian Soyuz and Progress space craft were the only vehicles able to get crews and equipment up to the station and back — and NASA paid Russia hundreds of millions of dollars for the transportation.

In recent years, space relations have seen some testy moments. In August, a malfunctioning Russian module nearly knocked the space station off its orbit. In 2018, a Soyuz booster failure sent a space crew hurtling back to Earth in an emergency landing. Also that year, a mysterious hole was found in one module at the station, prompting a small leak of oxygen.

No explanation for the hole has been revealed publicly to date; NASA has repeatedly directed questions to Roskosmos.

In August, an unnamed “high-ranking official in the Russian space industry” was quoted as saying that there were in fact eight man-made holes. Moreover, the Russian official also asserted that a NASA astronaut on board at the time had experienced a medical problem that “could have provoked an acute psychological crisis,” which, in turn, might have led her to seek a way to return to Earth before the mission was over.

NASA officials pushed back publicly in support of the U.S. astronaut.

Weeden said that there had been some international discussions about banning anti-satellite weapons, and that the Russian test could have been an effort to try out the system before the entire technology is banned. “Why build it if you’re not going to test it?” he said.

Langbroek, the Dutch researcher, called Moscow’s responses to criticism over the anti-satellite “typical Russian response denying responsibility; denying they did anything wrong.”

“Everyone knows that any anti-satellite debris at this altitude will cause problems, it’s a denial that really has no value,” he said.

The altitude at which the Russian satellite appeared to have been destroyed — around 490 kilometers — means that the fragments won’t disappear after a few hours but in months, if not years, he said. “It’s not a short-term time problem, it’s a longer-term [one],” he said.

He said the fact that the entire crew of the space station was forced to take emergency refuge, Russians included, indicated that Roskosmos likely was not aware ahead of time.

As for the question whether this was an error — the missile was not intended to destroy the satellite — Langbroek dismissed the speculation. “I don’t think you make mistakes like that. You don’t target an object at this altitude if there’s any danger of that,” he said.

“I really don’t believe this could be a mistake.”

- Mike Eckel is a senior correspondent in Prague, where he reports on developments in Russia, Ukraine, and around the former Soviet Union, as well as news involving cybercrime and money laundering. Before joining RFE/RL in 2015, he worked for the Associated Press in Moscow. He has also reported and edited for The Christian Science Monitor, Al Jazeera America, Voice of America, and the Vladivostok News.