Antonio Negri: A Philosopher Of ‘Operaismo’ And A Citizen Of ‘Catastrophe’ – OpEd

By K.M. Seethi

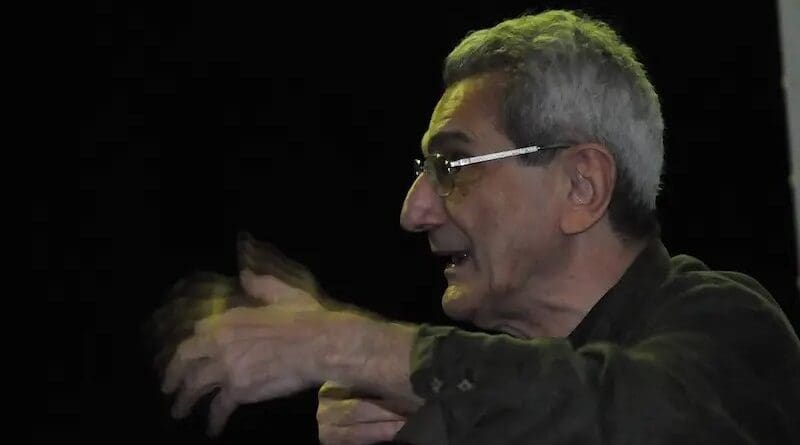

Antonio Negri, the renowned Italian political theorist and Marxist philosopher, passed away at the age of 90 in Paris on 16 December. Negri also carried different characterisations such as a post-Marxist and a confused postmodernist. Best recognized for his contributions to autonomism, Negri played a significant role in the establishment of the Potere Operaio (Worker Power) group in 1969 and was a prominent member of ‘Autonomia Operaia.’ Alongside his coauthor Michael Hardt, Negri earned international attention and criticism alike for their influential volumes that sparked widespread discussion. Negri served as a professor of philosophy and political science at the Universities of Padua and Paris.

Hardt and Negri significantly popularized workerism (operaismo), a political analysis aligned with autonomism that centres on empowering the working class. They defined operaismo by leveraging Marx’s idea that capital reacts to the actions of the working class, highlighting the active role of the working class and the reactive nature of capital. The theory contends that ongoing struggles of the working class influence technological and political changes, citing instances such as the correlation between strikes and the introduction of machines.

In the late 1970s, Negri faced accusations, including being the alleged mastermind of the left-wing militant organization Red Brigades and involvement in the May 1978 kidnapping of Aldo Moro. While the court couldn’t conclusively establish these connections, Negri was convicted in 1984 and sentenced (in absentia) to 30 years in prison. An additional four years were given for being ‘morally responsible’ for political activists’ violence in the 1960s and 1970s.

Negri endured four years in prison while awaiting trial, during which he was elected to the Italian legislature as a representative of the Radical Party. Although initially released on parliamentary privilege, this freedom was later revoked by the Italian Chamber of Deputies. Opting not to return to prison, Negri sought refuge in France with the assistance of Amnesty International and Félix Guattari. In France, he secured a position at the University of Paris VIII in Saint Denis, collaborating with intellectual luminaries like Alain Badiou and Gilles Deleuze. It was during his tenure in Paris that Negri encountered a young student named Michael Hardt, marking the beginning of a prolific collaboration spanning several decades. In 1997, Negri voluntarily returned to Italy to serve his sentence, aiming to draw attention to the plight of numerous political exiles engaged in radical activities in the 1960s and 1970s. His sentence was later commuted, and in 2003, he was released. Negri’s time in prison proved productive, yielding collaborative works with Hardt, including The Labor of Dionysus (1994) and the internationally acclaimed Empire (2000).

In the realm of continental philosophy during the late 20th and early 21st centuries, Negri, alongside influential thinkers such as Althusser and Deleuze, emerged as a central figure in a movement often referred to as French-inspired Neo-Spinozism. This philosophical orientation draws inspiration from the ideas of the 17th-century philosopher Baruch Spinoza.

In an interview, Negri said: “ it was precisely in Spinoza that we sought and found a principle of freedom that opened up the given being, our condition as defeated….Spinoza told us that divine does not mean transcendence (but I already knew this), but rather a plural horizon of immanence, populated by infinite ways of existence, therefore with infinite capacity of singularities to build the world, not as solitary individualities but as multitudes of singular ways. My atheism then lost even the appearance of a subtle negation of transcendence: the Spinozian God was built from the bottom of ethics, in the work of singularities. Immanence was constructive freedom.”

Negri’s contributions to Neo-Spinozism involve a reinterpretation and extension of Spinoza’s concepts, infusing them with contemporary relevance. The philosophy explores themes such as immanence, power, and the relationship between the individual and the collective. Like Althusser and Deleuze, Negri’s engagement with Neo-Spinozism reflects a departure from traditional philosophical frameworks, offering a fresh perspective on issues of subjectivity, politics, and social organization.

The release of Empire marked a decisive moment pushing Negri and Hardt to the forefront of critical theory. Published shortly after the influential ‘Battle in Seattle’ in November 1999, a key event for the global anti-globalization movement, the book offered a hopeful message. Hardt and Negri introduced the concept of Empire, a new form of sovereignty emerging since World War II, which they argued was global in nature and more influential than any nation-state. They contended that globalization, encompassing new global processes in manufacturing, labour management, and finance, was reshaping the composition of capital and giving rise to a novel class, termed the multitude. This, in turn, signalled a new chapter in the history of class struggle. At a time when many Left-leaning thinkers were expressing concerns about the ascent of neo-conservatism, Hardt and Negri’s work provided a refreshing perspective, leading to the widespread success of Empire as a bestseller.

The concept of Empire says that the contemporary regime of globalization represents a new form of sovereignty. It suggests that sovereignty has evolved into a structure comprised of various national and supranational entities, all unified by a singular logic of rule. According to this perspective, the current global manifestation of sovereignty is what Negri and Hardt term Empire.

According to Slavoj Žižek, what Hardt and Negri present in Empire is essentially a modern reimagining of The Communist Manifesto. According to Žižek, the book convincingly illustrates how global capitalism inherently produces conflicts that will ultimately lead to its unravelling. Žižek says that Empire not only challenges the complacent liberal proponents of the ‘end of history’ but also serves as a critical blow to pseudo-radical Cultural Studies, urging for a comprehensive engagement with the realities of contemporary capitalism.

Negri outlines a global power structure without a central authority in his description of Empire. Despite an unprecedented accumulation of power, sovereignty is decentralized in modern capitalism, creating a political order distinct from nineteenth-century imperialism and leading Negri to use the term Empire. The power structure has levels, including “apexes and summits of imperial power.” According to Negri, sovereign power is widely dispersed in a network fashion, although “Commonwealth” paints a somewhat uneven picture of a global ‘aristocracy’ atop various power pyramids, whether in states or corporations. The argument consistently maintains that even the strongest centres can, at best, conduct police operations and require assistance from other network components.

Simultaneously, Empire says that the system has become total in a certain sense. There is no external or transcendent ethical standpoint to effectively criticize its operations. While echoes of Foucault are present, Negri’s model is not one of universal capillary power or postmodern fragmentation. The dispersed sovereignty of the ‘Empire’ is identified as a system of domination, specifically capitalist domination. In Empire, capital and sovereignty converge, forming a system designed to perpetuate global exploitation and wealth accumulation in the hands of a privileged few.

Following Empire, Negri and Hardt published Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire in 2004. The book explores the emerging possibility of global democracy, a concept considered for the first time. The authors go into what they term the ‘project of the multitude,’ expressing a desire for a world characterized by equality and freedom. This project not only envisions an open and inclusive global democratic society but also outlines the means to achieve it. Multitude thus engages with the potential for a democratic transformation on a global scale. It contends that war has become a necessary and endemic component of the global order, with military force seen as essential for the functioning of the world market. In contrast to some globalization theorists, Negri sees global societal changes as reactive responses by capital to pressures from below, emphasizing grassroots movements and societal forces as drivers of transformation.

In 2009, the trilogy concluded with Commonwealth (Belknap Press), emphasizing the concept that a democracy of the multitude is conceivable and achievable because of our shared participation in the common. The term ‘common’ embodies the material wealth of the world, including air, water, soil, and nature’s resources. Moreover, it extends to the social products necessary for interaction and production, such as knowledge, languages, codes, information, and affects. This perspective sees humanity not as separate from nature but emphasizes practices of interaction, care, and cohabitation in a shared world. The focus is on fostering beneficial and limiting detrimental aspects of the common.

Negri has contributed significantly to political literature with various articles and books. Some notable works include The Porcelain Workshop: For a New Grammar of Politics (Semiotext(e) 2008), Time for Revolution (Continuum, 2003), Negri on Negri: In Conversation with Anne Dufourmantelle (Routledge, 2004), and Subversive Spinoza: (Un)Contemporary Variations (edited by Timothy S. Murphy, Manchester University Press, 2004). Other works include Insurgencies: Constituent Power and the Modern State (University of Minnesota Press, 1999) and The Politics of Subversion: A Manifesto for the Twenty-First Century (Polity Press, 1989).

In 2012, Negri brought out Declaration, a pamphlet on the Occupy movements. Furthermore, he collaborated with Hardt on Assembly (Oxford University Press, 2017), a book exploring the power of collective political action. The title Assembly reflects the idea of coming together and engaging in political action in concert. It offers a significant analysis of contemporary politics, going into various aspects of capitalism shaped by neoliberalism, finance capital, nationalism, and digital dynamics. The book critiques both capitalism and bureaucracy while advocating for progressive social movement politics. It calls for a rethinking of left-wing strategies, emphasizing the dialectics of movement/leadership, spontaneity/organization, and revolution/reform. The appropriation of fixed capital is a key element in their proposed strategy, termed the “new Prince” and the “entrepreneurship of the multitude.”

In his trilogy—Empire, Multitude, and Commonwealth—Negri presents an altermodernity thesis, asserting the obsolescence of the old class structure and dynamics. Departing from traditional dialectics, he introduced a new logic of history marked by endless diversity rather than growing class homogeneity. Negri’s departure from dialectical orthodoxy is often overlooked. Influenced by Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus, he terms this diverse ensemble ‘multitude,’ drawing inspiration from Spinoza. In his view, the postmodern multitude is a collection of singularities.

Raewyn Connell critiques Negri’s works, particularly Empire and Commonwealth, pointing out a notable absence of concrete knowledge in the discussion of power. Connell highlights that while Negri presents a theory of global capitalism in crisis, there is a lack of analysis regarding actual multinational corporations, their strategies, or problems. Similarly, discussions about a global aristocracy in Commonwealth lack specifics about their power. Connell notes that Negri extensively discusses theories of sovereignty but fails to analyse particular regimes and their ruling techniques or how they address problems. This renders the concept of “power” as an abstract postulate rather than a sociological reality.

Furthermore, Connell emphasizes the vagueness of the ‘multitude’ as a social entity, echoing criticism from others. Alex Callinicos suggests that the idea of the multitude is more an expression of good intentions than a tool for class analysis. Giovanni Arrighi, in a brief contribution to the debate about “Empire,” criticizes the heavy reliance on metaphors and theories while systematically avoiding empirical evidence. Arrighi argues that as a result, some key claims about globalization in the book are simply false.

Samir Amin criticized Hardt and Negri’s theses, arguing that their assertions rest on two flawed premises. First, they claim that globalization has rendered national policies obsolete, dismissing the concepts of nation and national interest. Second, they argue that there is no more imperialism, only an ‘empire’ with no central power. Amin contends that these propositions are false and emerged from a lack of understanding of the history of capitalist globalization. He asserted that imperialism persists as the mobilization of economic, political, and military means to subjugate peripheries to the dominant centres, a dynamic evident throughout history.

The shaping of peripheral capitalist societies has led to distinct forms of proletarianization, varying across regions based on assigned functions. These forms differ from those in dominant centers but are complementary. The apparent ‘multitude,’ representing the diverse global working classes, is structured differently from one country or phase of global capitalist development to another. Negri’s error is evident in his call to vote for the European constitution, believing it would hinder neoliberal capitalism by challenging the nation-state. Amin argues that Negri fails to see that European construction aims to consolidate, not weaken, this development. The apparent reduction in state functions is not to empower civil society but to eliminate its potential to protest. The Brussels pseudo-state’s diktats serve to strengthen the reconstruction of national states as exclusive servants of capital. Amin contrasts this with the Washington establishment’s understanding that Hardt and Negri deny. The control of globalization by imperialist powers involves a geostrategy of military control, a point downplayed by Hardt and Negri, according to Amin.

In an article in New Left Review in 2019, Negri and Hardt reflected on the shifting dynamics of globalization, noting its resurgence as a central issue. They observe a range of reactions, from the decline of the liberal international order to calls for national sovereignty. The authors argue for a transition from class-focused struggles to a multitude framework, aligning with intersectional analysis and the recognition of multiplicity in addressing various forms of domination. They emphasize the importance of understanding subjectivities in relation to diverse structures of domination.

Negri, having maintained a consistent hostility towards 20th-century socialism and the Soviet Union, eventually evolved into an advocate for modern social democracy, particularly in the later years of his life. In May 2005, he endorsed a ‘Yes’ vote in support of the proposed EU constitution during the referendum in France.

He expressed the view that he never considered the European Union as a constraint on the working class but rather saw it as a suitable arena for working-class struggle in the era of globalization. Despite differing from leftist forces, he supported referendums on the European Constitution. Particularly in the present period marked by a relative decline in American power, he believes a united Europe could serve as a powerful democratic alternative, fostering the invention of new life forms. He deems nationalist ideologies, even within patriotic movements, as inherently reactionary. In the current context of global reorganization dominated by the U.S., he advocated for the European Union’s disengagement from NATO, urging it to position itself as the heir to anti-fascism and socialism of the 20th century, reinforcing aspects like welfare and the culture of rights.

In an interview, Negri reflected on the defeat of socialism and the violent overthrow of communism. He described postmodernism as the current ideological framework legitimizing a global restoration of capitalist power. Having personally experienced the defeat of the class struggle and violence against the exploited, poor, and excluded, he identified himself as a citizen of this catastrophe. Despite the solitude of defeat and imprisonment, he maintained a recognition of the enemy and a sense of possible rebirth. Acknowledging the ongoing war between the West and the East, both incapable of producing freedom, he expressed a desire for them to weaken each other. From the resulting grief, suffering, and misery, he foresaw the possibility for a new strength to emerge—one that vehemently rejects war and envisions peace as the essential condition for human life.