Politics Block Solution As Mounting Debt Threatens China – Analysis

China’s leaders fail to tamp down corporate debt levels or expectations of government bailouts should financial troubles emerge.

By Chris Miller*

As leaders of the Chinese Communist Party assembled at their secretive annual conclave at the Beidaihe seaside resort, one might think that, from an economic perspective, they could relax on the beach with few worries. Unlike in 2015 and 2016, fears that declining foreign exchange reserves would force a devaluation of China’s currency, the renminbi, have receded. Thanks to stricter capital controls and rebounding confidence in China’s growth prospects, the outflow of capital has slowed. China’s currency has even appreciated over the course of 2017. But underneath the hopeful signs a crisis is growing, and vested interests make it hard for party leaders to tackle the issues before the crucial Party Congress later this year.

The most serious dilemma China faces is not its growth rate or the value of its currency, but a tremendous buildup of debt. China’s biggest firms – many state-owned – have accumulated debt at a rate and scale with few precedents in recent history. Though China’s GDP continues to grow rapidly, the country’s debt burden has grown faster still since the 2008-2009 crisis. Chinese leaders realize that although the debt is mostly domestic something must change, but they cannot agree about who should bear the cost of reducing debt growth. All tough decisions are on hold at least until this autumn’s 19th Party Congress, when China’s leadership will be reshuffled.

Yet the longer China fails to slow debt growth, the more it risks a financial crisis as lenders lose confidence in Beijing’s ability to maintain financial control.

Unlike the United States before the 2008 crash, China’s households do not have an outsized debt burden. According to data from the Bank of International Settlements, obligations of Chinese households stand slightly above 40 percent of GDP, compared, for example, to 92 percent in South Korea. China’s central government is also not particularly indebted, with Beijing owing only 45 percent of GDP of obligations to creditors. Many Western governments have twice that level of indebtedness.

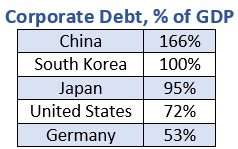

China stands out in the debt levels of its corporate sector, equivalent to 166 percent of GDP. That compares with 72 percent in the United States, 95 percent in Japan, 100 percent in South Korea, and 53 percent in Germany. Excluding small countries that operate as financial hubs, China’s corporate debt figure is among the highest on record.

The growth in Chinese corporate debt has been spectacular since the global financial crisis. Before 2008, China’s ratio of corporate debt to GDP was declining. When the crisis hit, a bout of government-backed stimulus lending from state-owned banks increased corporate indebtedness by more than 20 percentage points to above 120 percent of GDP. That much was understandable: Debt often increases as a result of stimulus. But then in 2011, Chinese corporate debt restarted its march upward, increasing from around 120 percent of GDP to over 160 percent today.

If lenders begin to fear that borrowers can’t repay their debts, they may cut lending or increase interest rates. This would force cuts to corporate investment – which has driven Chinese GDP growth – and could threaten the solvency of China’s biggest firms.

Specifics of China’s financial system have made a financial crisis less likely in the short term, but also made it more difficult for the government to change corporate behavior in a way that would reduce financial risk. Much of the corporate debt buildup is by China’s state-owned firms. In contrast to the West, China’s government plays a major role in the industrial sector, owning firms in sectors spanning from telecoms to tourism, and many lenders view these firms as having an implicit government guarantee – the firms borrow massive sums at low interest rates, with banks assuming that the government will bail them out if financial trouble emerges.

Specifics of China’s financial system have made a financial crisis less likely in the short term, but also made it more difficult for the government to change corporate behavior in a way that would reduce financial risk. Much of the corporate debt buildup is by China’s state-owned firms. In contrast to the West, China’s government plays a major role in the industrial sector, owning firms in sectors spanning from telecoms to tourism, and many lenders view these firms as having an implicit government guarantee – the firms borrow massive sums at low interest rates, with banks assuming that the government will bail them out if financial trouble emerges.

At the same time, China’s biggest banks are also state-owned and believed by many to benefit from the same implicit guarantee. Such banks can borrow far more cheaply than they would otherwise be able to do. This enables them to lend yet more to Chinese firms, thus staving off short-term crisis but increasing the scale of the adjustment that will at some point become necessary. Some analysts argue that China need not worry because the bulk of its debt is domestic and not at risk of foreigners pulling out their money. China is at risk, however, of Chinese savers pulling their money out of short-term financial products. This happened in 2007 and 2008. The US market for corporate paper – short term corporate debt instruments similar to those used in China’s vast shadow banking market – froze and firms found themselves unable to refinance.

China’s leaders, of course, realize the risk. In late 2016, Beijing began treating “financial security” as a national security risk. Chinese President Xi Jinping has made repeated statements stressing the need for “supply side structural reforms,” and his economic adviser Liu He has called for deleveraging – cutting debt levels. Beijing has coupled this rhetoric with some restrictive measures. Earlier in 2017, China’s central bank and financial regulatory bodies tightened rules governing short-term lending products. China is also beginning to experiment with allowing lossmaking companies to go bankrupt – previously it kept ailing firms alive with infusions of new credit – though the overall number of bankruptcies remains small. More recently, Beijing has cracked down on prominent and politically well-connected firms such as Anbang, HNA and Dalian Wanda, which raise money in China to buy assets abroad.

Yet despite the talk from Beijing, action on reducing debt levels remains insufficient. China’s corporate debt as a share of GDP did decline slightly in late 2016, from 166.8 percent to 166.3 percent of GDP. But the minor reduction in the growth rate of corporate debt has been counteracted by rising household debt. As recently as 2013, household debt was 30 percent of GDP and is now at 44 percent of GDP and rising. Government debt is growing, too. China’s aggregate debt levels keep climbing.

Despite rhetoric about reform and deleveraging, Beijing has failed to slow debt growth. The reason is politics. Most Chinese elite realize that debt growth must slow – but several crucial political constituencies correctly fear that reducing debt would also reduce available resources. It’s not a coincidence that management of the major state enterprises and financial institutions is dominated by children of senior leaders.

Some firms might face insolvency if interest rates rise or bank loans dry up, and others would face higher costs. Thus the bosses of state-owned firms lobby heavily against any reduction in credit provision. Similarly, China’s powerful real estate sector relies heavily on cheap bank loans to fund its rapid construction rate. A reduction in credit growth would threaten the stability of the real estate sector. Local governments, meanwhile, depend in part on land sales for funding. Any measure that hit the real estate market would also reduce the resources available to local governments.

Even as Beijing talks about reducing financial risk, a powerful array of political interests are aligned in favor of retaining the current system, whatever dangers it might pose. In advance of this autumn’s Party Congress, Xi is focused on placing his allies into leadership positions, spending political capital on that battle rather than push for financial reform. China’s leaders may refocus on the debt dilemma after the Party Congress. If not, China’s debt burden will only increase – as will the risk of a crash.

*Chris Miller is associate director of the Brady-Johnson Program in Grand Strategy at Yale. He is the author of The Struggle to Save the Soviet Economy.