Harm From ‘De-Risking’ Strategies Would Reverberate Beyond China – Analysis

By Diego Cerdeiro, Siddharth Kothari and Dirk Muir

China’s importance in the global economy has increased dramatically in recent decades, and it has been a particularly crucial driver of trade integration in Asia.

China’s medium-term growth prospects, like that of other countries, will be determined in part by major forces such as convergence to advanced economies’ income levels and demographics. Yet key structural policy drivers, including domestic reform momentum, and external factors, including geoeconomic fragmentation, also significantly affect this path.

What would be the potential implications for Asia and beyond from these different growth paths? In our latest Regional Economic Outlook for Asia and the Pacific, we assess the potential effects of a downside scenario from ‘de-risking’ between China and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development economies.

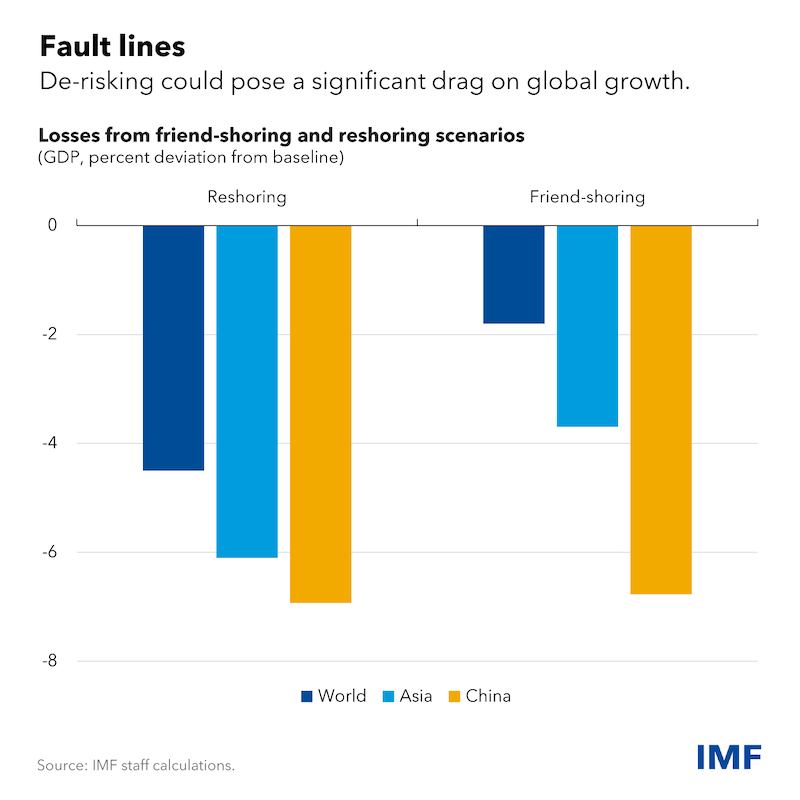

As the Chart of the Week shows, so-called de-risking strategies by China and the United States and other OECD countries that aim to reshore production domestically or friend-shore away from one another can result in a significant drag on growth around the world even assuming no new trade restrictions with third countries—especially in Asia.

While reshoring would be particularly painful to everyone, it is notable that friend-shoring does not generate net benefits for third countries in the long term. That’s because the benefits from trade diversion are offset by the effects of the contractions in both China and the OECD.

For the region, the results suggest that third countries should not expect to passively benefit from friend-shoring policies, but rather actively pursue reforms that can help them further integrate into global supply chains. For systemic economies around the world, there is an urgent need for constructive dialogue to resolve underlying sources of tensions and resist costly fragmentation outcomes.

In China, the risks that fragmentation poses on medium-term growth underscore the need for comprehensive structural reforms that would help income levels converge more rapidly with those in advanced economies—such as closing productivity gaps between state-owned and private firms and further opening up sectors to competition. Our research shows that achieving this would also have significant positive spillovers for other economies in Asia.

About the authors:

- Diego Cerdeiro is an economist at the IMF, currently working in the Regional Studies division of the Asia and Pacific Department. He has done research on international macroeconomics, international trade, and network theory. He obtained his PhD from the University of Cambridge.

- Siddharth Kothari is an economist in the IMF’s Asia and Pacific Department, where he currently works on the China team. His main research interests are in macroeconomics and development. He holds a PhD in Economics from Stanford University.

- Dirk Muir is a Senior Economist at the IMF in the Research Department’s Economic Modeling Division, focusing on the international macroeconomic dimensions of climate change mitigation, global fragmentation, global rebalancing, and oil markets. He has worked on Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, and Thailand and been the mission chief for Vanuatu.

Source: This article was published by IMF Blog