West African Governments Can Learn From The US Police Reform Movement – OpEd

By Michael Keen and Dr. Sam Cherribi

By most measures, the United States and Mali are worlds apart. However, both face a common problem: security forces in both countries have a history of brutality against certain communities, and this brutality has reached crisis proportions in recent years. In the US, local police forces kill Americans of color at staggeringly disproportionate rates.

In Mali, and increasingly in Burkina Faso and Niger as well, militaries are fighting a bloody insurgency spearheaded by Al Qaeda-linked groups. In the process, though, the militaries are killing even more civilians than are the jihadists—atrocities have been documented by NGOs and the UN (repeatedly) and even acknowledged by government officials.

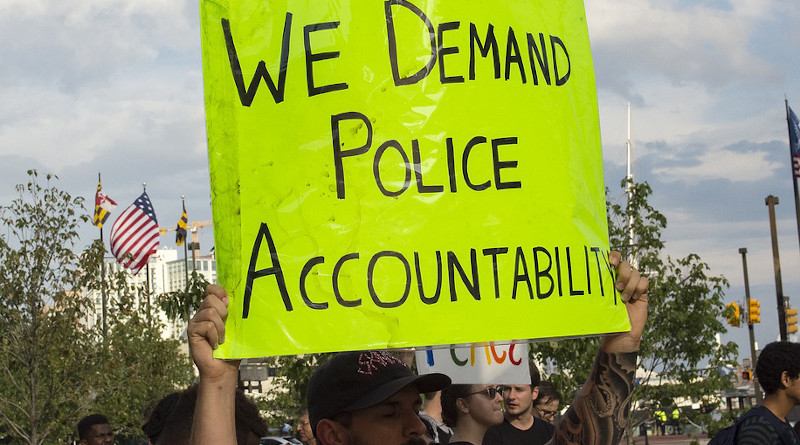

For Mali and its neighbors, ending violence against civilians by those responsible for protecting them is key to rolling back and eventually defeating jihadist groups: state violence against civilians provides a huge boost to jihadist recruiting, and security forces’ atrocities have contributed to a culture of impunity that has toxified national politics from Mali to Nigeria. The Black Lives Matter movement in the United States and American police reform efforts have illuminated five lessons that West African governments should apply in conducting their counterinsurgency operations.

Lesson 1: Classroom training on respecting human rights will not bring change alone

In the US, numerous studies have shown that Americans of color, especially Black Americans, are disproportionately likely to be killed by police. A common solution floated by reform advocates is racial sensitivity and implicit bias training. American police departments have responded: per one report, 69% of American police departments claimed to have provided such training. However, as a 2017 Atlantic article put it, “But even as the classes spread, it’s not clear whether they actually work.” At the very least, implicit bias training is no magical cure—its widespread adoption has not stopped the epidemic of police violence in the US.

The story in Mali is similar. Malian security services have received extensive training in human rights from the EU, the US, and Malian NGOs. Classroom teachings are not followed in the field, though, and all this training has had little effect. Indeed, it may have contributed to other problems—for example, the leaders of both the 2012 military coup and the 2020 military coup in Mali trained in the US.

More PowerPoint presentations on human rights will not make a difference. Concrete action is needed.

Lesson 2: There is no substitute for genuine accountability

In September 2020, Kentucky’s attorney general announced that one of the three police officers involved in the killing of Breonna Taylor would face criminal charges (though not actually for killing Taylor). The week before, the Louisville, Kentucky government announced Taylor’s family would receive a $12 million settlement. Although many American activists and political leaders had hoped all three officers would face greater charges, an officer facing prosecution and a multimillion-dollar civil settlement far exceeds the standard level of accountability in Mali. Despite overwhelming evidence of years of pervasive and lethal brutality, to this day, no Malian soldier has been prosecuted for extrajudicial killings of civilians in the areas most impacted by the insurgency.

Until individual soldiers are prosecuted and convicted for carrying out extrajudicial executions and until commanders publicly acknowledge their institutions’ bloody legacies, jihadist groups will not be defeated, and the bloodletting across the region will continue.

Lesson 3: Symbolic breaks from the past can help, but community input is more important still

A rallying cry of recent protests calling for police reform in the US has been “abolish the police!” The slogan channels a desire for a radical break with the failed approaches, structures, and institutions of the past. A few jurisdictions in the US have actually “abolished” their police. Camden, New Jersey, is among the highest-profile.

In 2012, Camden’s government disbanded and rebuilt its entire police force. Subsequent years saw a drop in violent crime and drastically fewer complaints about the use of excessive force by police. As a result, Camden is touted as a model for other municipalities. However, what really happened in Camden is more complicated. The departmental reshuffle was primarily a cost-cutting move, and most former officers were immediately hired back; the new department initially continued old policing methods. The subsequent drop in crime happened across New Jersey, not just in Camden. Most importantly, complaints about excessive force did not drop until community pressure forced reforms to police guidelines, independent of the initial police reboot.

In Mali, the closest parallel to Camden’s experience has been the formation of the G5 Sahel. The G5 Sahel (consisting of Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad, and Mauritania) aims to improve coordination on regional security challenges, and has also been an important vehicle for external security assistance to Mali. Unfortunately, putting Malian troops under the command of the G5 Sahel has not ended atrocities: the Malian soldiers responsible for a 2018 massacre were hatted under the G5 Sahel at the time.

In both the US and West Africa, cosmetic institutional changes are less important than correcting the personnel and practices that have worked so disastrously.

Lesson 4: When attempting reform, expect institutional pushback

In the US, even where government leaders have sought to implement reforms to reduce police brutality, police forces have taken direct action to undermine attempts to hold officers accountable. For example, in June 2020, when Atlanta’s district attorney announced the officer who shot unarmed man Rayshard Brooks would face murder charges, dozens of Atlanta police officers simultaneously called in sick.

In Mali, the security forces hold more power over the ostensibly civilian government. Perceptions the government was not sufficiently supporting the military helped fuel protests in both 2012 and 2020, both of which led to military coups. Although these protest movements were not explicitly linked to government attempts to reform the security forces, the military having overthrown the government twice in the last decade means Malian leaders must tread gingerly in pushing through reforms needed to address brutality against civilians. In neighboring countries, militaries have also had major roles in recent political movements—in Niger, overthrowing President Mamadou Tandja in 2010, and in Burkina Faso, playing a key part in President Blaise Compaoré’s 2014 resignation. If the security forces feel threatened by reform efforts, they will respond. Civilian leaders must then find a path forward.

Lesson 5: To prevent abuses, know the limits of security force

As American police killings come under increasing scrutiny, one question has repeatedly come to the fore: should police have been called in the first place? American police today face many responsibilities only tangentially related to law enforcement. Redirecting these responsibilities to non-violent specialists has become a focus of reform efforts.

The same lesson applies to West Africa. Both local leaders and the international community must be more aware of which problems security forces are not equipped to fix. Security forces alone cannot rebuild the schools destroyed by jihadists. They cannot inject money back into local economies. They cannot rebuild the state’s credibility as a neutral mediator in disputes over resource access. They cannot singlehandedly reverse 60 years of discrimination and state violence.

Across the region, none of these problems will be solved by security forces killing more people. It is easy to claim that deeper issues cannot be addressed until violence is under control. But absent reform, a security-first approach will only perpetuate bloodshed. Civilians, including those living in remote, marginalized areas, deserve to be treated as humans worthy of respect, not as potential security threats to be at best controlled and at worst eliminated by the state.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com or any institutions with which the authors are associated.