Primer On Myanmar Elections: Six Things You Need To Know About The Elections – Analysis

By ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute

By Su-Ann Oh*

Myanmar will hold its general election on 8 November, and for the first time in decades, there will be real competition between political parties and candidates in a general election. Given the popularity of Aung San Suu Kyi and her party – the National League for Democracy (NLD) – we may be about to witness a pivotal moment in the political history of the country. This, however, is overshadowed by concerns over how the military will react if the NLD secures electoral success.

Fully aware of the complexities of politics in Myanmar, this article provides background information about the process and the players by addressing six questions:

1. Which seats are being contested?

2. Who is in the running?

3. What role do the ethnic parties play?

4. Who will be president?

5. Will the elections be free and fair?

6. Will the results be upheld or will the military step in?

WHICH SEATS ARE BEING CONTESTED?

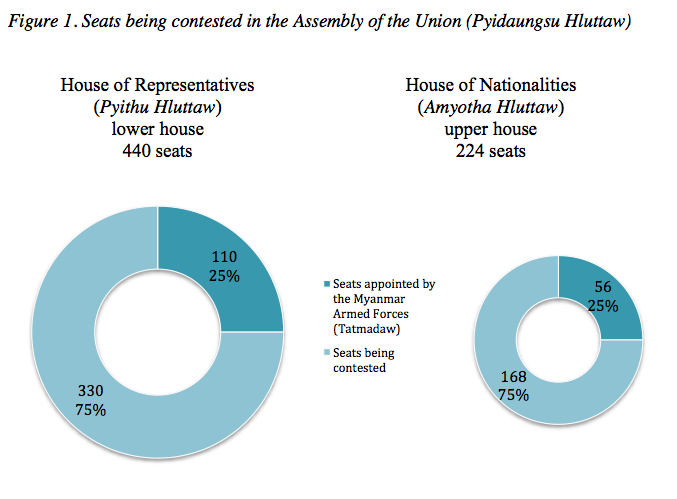

In all, 1,142 people will be elected to the Assembly of the Union (Pyidaungsu Hluttaw) and to the regional assemblies. The Assembly of the Union – the national-level bicameral legislature of Myanmar – is made up of a 440-seat lower house (House of Representatives, Pyithu Hluttaw) and a 224-seat upper house (House of Nationalities, Amyotha Hluttaw).

As Figure 1 shows, 25 per cent of the seats in the Assembly are reserved for members appointed by the Myanmar Armed Forces (Tatmadaw), as enshrined in the 2008 Constitution. In all, 330 seats in the lower house and 168 seats in the upper house will be contested. The constituencies for this year’s general election will be the same as those in 2010.

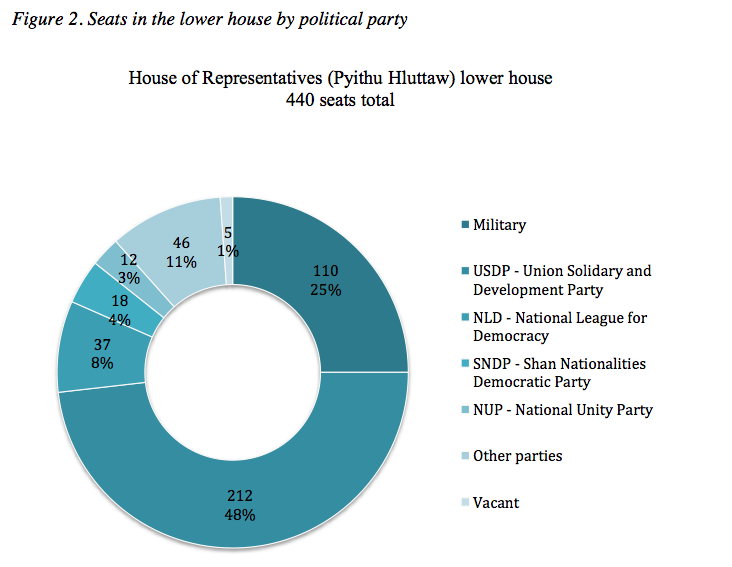

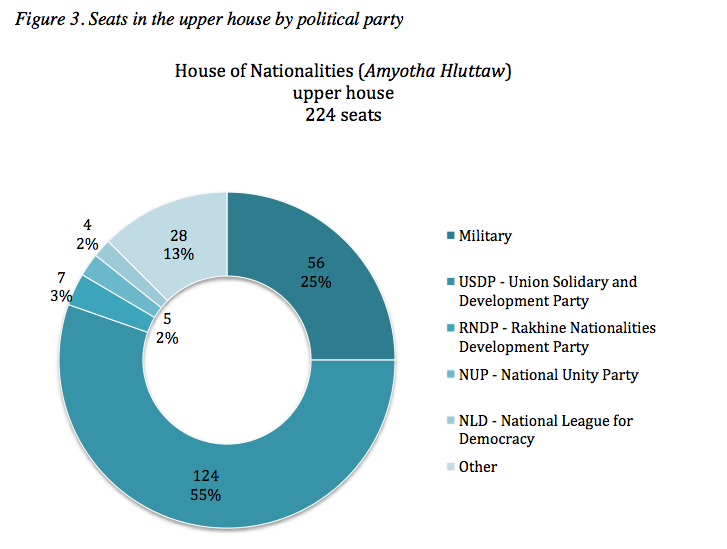

At present, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) – the ruling party – holds altogether 336 seats in the upper and lower houses. These were won in the general election in 2010 which had been boycotted by the main opposition party, the National League of Democracy (NLD). The NLD has 41 members of parliament who were elected during the by- elections in 2012 (see Figures 2 and 3).

In the lower house, the government, consisting of the USDP and the military holds 322 seats, while the other political parties hold 109 seats. The political parties in the ‘other’ category include the Rakhine Nationalities Development Party, the National Democratic Force, the All Mon Region Democracy Party, the Pa-O National Organization, the Chin National Party, the Chin Progressive Party, Phalon-Sawaw Democratic Party and the Wa Democratic Party. Shwe Mann, a former general and member of the USDP, was the elected Speaker of the lower house for the first two years. His post was later given to Khin Aung Myint, a former general.

In the ‘other’ category, a host of parties holds a small number of seats each and they include the All Mon Region Democracy Party, the Chin Progressive Party, the National Democratic Force, the Shan Nationalities Democratic Party, the Phalon-Sawaw Democratic Party, the Chin National Party among others. Khin Aung Myint, senior official of the Myanmar military government and a Major General, was elected Speaker of the upper house and Chairman of the Assembly of the Union.

Regional elections will take place as well in each of the 14 major administrative regions and states. Myanmar is divided into 21 administrative subdivisions (by state, region, union territory, self-administered zone, self-administered division).

However, members will be elected for the 14 administrative areas consisting of seven regions and seven states (see map in Figure 4), each with their own Assembly (Region Hluttaw or State Hluttaw); once elected, they will also be involved in the Leading Body in self-administered zones and divisions. The regions – Ayeyarwady, Bago, Magway, Mandalay, Sagaing, Tanintharyi and Yangon – are predominantly ethnically Bamar. The states – Chin, Kachin, Kayah, Kayin, Mon, Rakhine and Shan – on the other hand, have higher proportions of minority ethnic populations. The difference in ethnic composition has important implications on the election as ethnicity is highly political, politicized and part of the political infrastructure of the country.

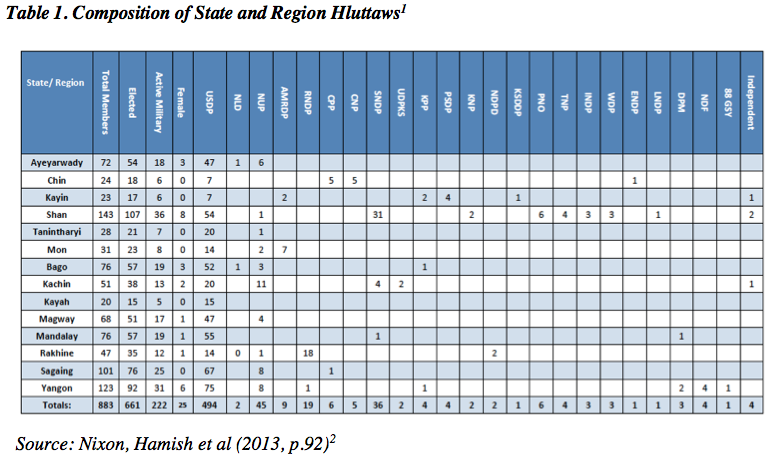

During the elections, 644 seats will be contested in these regional parliaments. The Shan State and Yangon Region have the largest Hluttaws at 143 and 123 seats respectively, while the Kayah State and Kayin State Hluttaws are the smallest at 20 and 23 respectively (see Table 1). In addition, 29 constituencies for regional or state parliaments for national races will also be contested.

Currently, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) holds the majority of the seats in all State and Region Hluttaws except in Rakhine State where the Rakhine Nationalities Development Party dominates. As Table 1 shows, there is a wide variety of political parties in these assemblies, including a host of ethnic-based ones.

WHO IS IN THE RUNNING?

In all, 90 parties3 have submitted more than 5,8004 candidates and more than 3005 have registered as independent candidates. The USDP, NLD and the NUP (National Union Party) have the highest number of candidates.6 However, the main battle will be fought between the USDP and the NLD.

The USDP registered as a political party in June 2010 and is the successor of the Union Solidarity and Development Association. The latter was formed by the military junta in 1993 as a way of mobilizing the masses to support the military, and “to perpetuate its influence in the society and carry out its policies.”7

In what appears to be a purge of the ranks, Shwe Mann has since been removed as head of the USDP. It is speculated that this has been done to pave the way for Thein Sein’s second term as president, to curb Shwe Mann’s efforts to reduce the military’s influence in parliament and the perception that he has been working in alliance with Aung San Suu Kyi.

The USDP has nominated more than 1,000 candidates nationwide. Among these are 45 senior officers who have retired from the military.8 Although the USDP is generally considered by international commentators to be unpopular, its candidates may win in many rural areas as they are seen to be able to meet local needs.9 It appears that the recent floods are another opportunity for the USDP and the NLD to further their political goals.10 The way in which the government handles the floods will, to some extent, determine how people will vote in these areas.11

It is generally believed that the NLD will do well in the elections, particularly in the Bamar- dominated constituencies. The party and its iconic leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, have long been viewed as stalwart and devoted proponents of democracy, having suffered persecution, imprisonment and personal loss for their cause.

The NLD was formed under the leadership of Aung San Suu Kyi in the aftermath of the 8888 Uprising, a series of protests against the military regime in 1988. In 1990, the NLD won 392 of the 492 available seats. However, it was unable to persuade the ruling military junta to transfer power over to it.12

The NLD is participating in the general elections after having boycotted them in 2010 during which the USDP won 70 per cent of the seats. However, in the by-elections of 2012, the NLD won 43 of the 45 seats on offer. It is widely believed that the geographic spread of seats suited the NLD because they were mainly in ethnic Bamar areas.

The NLD has fielded more than 1,000 candidates; but its choices have been challenged by its own members and those who were not selected. It has been argued that in rejecting all but one of the members of the ’88 Generation’ group – activists who took part in the 8888 Uprising – the NLD is “dissociating itself from the more radical elements” of its party.13 Nevertheless, this is but the first of a series of minor conflicts that are expected to occur and its impact on the NLD’s chances of success is as yet unknown.

The battle for votes will be determined by geography and ethnicity. In the seven central and southern regions where the Bamar dominate, it is expected that the NLD will dominate the polls. However, to obtain an overall majority, the NLD will need to win a substantial number of seats in the minority ethnic states as well. In these regions, strong competition will come from smaller local ethnic groups.

WHAT ROLE DO THE ETHNIC PARTIES PLAY?

The ethnic parties – all of which claim federalism and ethnic needs as priorities – can be classified into three main groups: those linked to the USDP, those connected to the NLD and those linked to neither. Most of the ethnic parties that contested in the 2010 election are from the first category – Rakhine State National United Party, Kayin State Democracy and Development Party, and the All Mon Region Democracy Party for instance. Although these were allied to the USDP during the 2010 election, they have since distanced themselves from a pro-USDP agenda.

Those parties allied with the NLD – Zomi Congress for Democracy, Shan Nationalities League for Democracy, Chin League for Democracy Party, Mon National Party, for example – seek to increase their influence through this association and strengthen their opposition to the USDP.

The ethnic parties in the third group were founded to represent their ethnic electorate, to promote equality and to support their ethnic identity. They include smaller parties whose aim is to limit their being discriminated by larger ethnic groups.14

The ethnic parties have formed several coalitions,15 two of which will be contesting in the elections: the Nationalities Brotherhood Federation (NBF) and the United Nationalities Alliance (UNA). Broadly, the NBF consists of the ethnic parties that successfully contested the 2010 election. The UNA, in contrast, was formed after the 1990 election and is “considered one of the most influential and experienced political alliances operating in the country”.16

The main strategic concern in the ethnic states is the competition with the NLD and the splitting of the ethnic vote. The NLD has not responded to a proposal from the UNA to not contest seats where UNA representatives will stand. 17 It appears that there will be an all-out fight for the ethnic vote. If the ethnic parties win a majority in the seven ethnic states, this could lead to a fragmentation of the local assemblies. Like Singapore and the UK, Myanmar uses the first- past-the-post (constituency-based) system in the general election. This means that the person with the most votes in a constituency is declared the winner and that in constituencies where three or more parties are running, it is difficult to foresee the outcome in many, if not most, instances.

WHO WILL BE PRESIDENT?

Although President Thein Sein has decided not to run in the general election, he has left the possibility of a second presidential term open. A recent amendment to the Constitution has made it possible for unelected representatives to become president. His fellow USDP member, Shwe Mann, has long expressed his desire to be president. It would seem, however, that his chances have diminished since his removal as head of the USDP.

At present Aung San Suu Kyi is not eligible to become president because Article 59F of the 2008 Constitution disqualifies anyone with “legitimate children” owing “allegiance to a foreign power”, i.e. with nationality of another country (Myanmar does not recognize dual citizenship) from doing so. However, if the NLD secures electoral success, pressure may be brought to bear on the military to alter this clause.18 As the selection of a president is likely to occur in the first quarter of 2016, there will be enough time for the NLD to campaign to remove Article 59F. Nevertheless, Aung San Suu Kyi would still need to garner the most votes during the selection in the Assembly, a veritable challenge given the different groups in the Assembly of the Union. As a quarter of the seats is occupied by the army, an anti-NLD coalition only needs a third of the elected seats to control who becomes president.

The selection process, which will involve much lobbying and voting, consists of three steps. First, the members of the Assembly of the Union divide into three groups: the elected representatives of the lower house, the elected representatives of the upper house, and the unelected army representatives. Each group puts forward a candidate and the three candidates are voted for in a joint session by all the elected and unelected representatives of both houses. The winner becomes president and the two losers become vice-presidents.

There has been speculation that a deal was made between Aung San Suu Kyi and Shwe Mann which might have involved the NLD backing Shwe Mann to be president, in return for him pushing through constitutional amendments to make Aung San Suu Kyi eligible to be president. Given that Shwe Mann has been sidelined in the USDP, the possibility of this plan succeeding is low.

Two names have since been tipped as possible NLD presidential candidates but it seems unlikely that they will run. Tin Oo, a former Commander-in-Chief of the Burmese army and a founding member of the NLD has announced that he is not interested.19 Win Htein, a former military officer, appears to be suffering from ill health.20

Finally, there are rumours that current Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing may be considering throwing his hat into the Presidency ring.

WILL THE ELECTIONS BE FREE AND FAIR?

There appears to be a strong drive to ensure that the elections are free and fair. The Union Election Commission (UEC) has collaborated with local civil society organizations to draft a code of conduct and to educate voters, and is willing to receive international observers during the elections. However, whether things will turn out that way may boil down to technicalities rather than will. One of the main obstacles that the UEC is facing is the capacity to produce accurate voter rolls. It has been in the process of computerizing more than 32 million21 voter names for the first time. This is a major undertaking and the electoral roll has been found to be riddled with inaccuracies. It is now issuing new identity cards, separate from existing National Registration Cards, that will guarantee the right to vote and will be useful in enhancing the accuracy of the voter list for future elections.22

WILL THE RESULTS BE UPHELD OR WILL THE MILITARY STEP IN?

Given Myanmar’s record, observers are leery of predicting what will happen after the results are announced. In an interview with the BBC, Myanmar’s Commander-in-chief Min Aung Hlaing asserted that the military would maintain a political presence until a peace agreement is reached with all the ethnic armed groups and that it would respect the results of the forthcoming general election.23 This pronouncement is believable as the military has a guaranteed 25 per cent block in the parliament, which it believes ‘safeguards’ the nation. Nevertheless, what the military will do if the NLD wins the majority of parliamentary seats remains to be seen.

CONCLUSION

The players are in place and the battle lines have been drawn. On 5 September, campaigning began in earnest: flags will be flown, gauntlets will be thrown down and marches will be stolen. One thing is for certain: we have many lively discussions and speculations of campaign strategies and poll results to look forward to in the coming months.

About the author:

* Su-Ann Oh is Visiting Fellow at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. She would like to thank ISEAS Perspective editors and reviewers for their help in editing and improving the draft of this paper.

Source:

This article was published by ISEAS as ISEAS Perspective 2015, Number 51 (PDF).

Notes:

1 USDP – Union Solidarity and Development Party, NLD – National League for Democracy, NUP – National Unity Party, AMRDP – All Mon Region Democracy Party, RNDP – Rakhine Nationalities Development Party, CPP – Chin Progressive Party, CNP – Chin National Party, SNDP – Shan Nationalities Democratic Party, UDPKS – Unity and Democracy Party of Kachin State, KNP – Kayan National Party, NDPD – National Democratic Party for Development, KSDDP – Karen State Democracy and Development Party, PNO – Pa-O National Organization, TNP – Taaung (Palaung) National Party, INDP – Independent, WDP – Wa Democratic Party, ENDP – Ethnic National Development Party, LNDP – Lahu National Democratic Party, DPM – Democratic Party (Myanmar), NDF – National Democratic Force, 88GSY – The 88 Generation Student Youths

2 Nixon, Hamish, Joelene, Cindy, Kyi Pyar Chit Saw, Thet Aung Lynn and Arnold, Matthew. State and Region Governments in Myanmar. Location unspecified: Myanmar Development Resource Institute (MDRI) Centre for Economic and Social Development (CESD) and The Asia Foundation, 2013.

3 Union Election Commission website. http://uecmyanmar.org/index.php/voters (accessed 24 August 2015).

4 The Global New Light of Myanmar. “UEC announces preliminary candidate lists”. 20 August 2015. http://globalnewlightofmyanmar.com/uec-announces-preliminary-candidate- lists/?utm_source=Daily+News+on+the+Southeast+Asian+Region+21+August+2015&utm_campaign=Info+Al ert+20150821&utm_medium=email (accessed 24 August 2015).

5 ibid.

6 ibid.

7 David Steinberg. “The Union Solidarity And Development Association: Mobilization and Orthodoxy in Myanmar”. Burma Debate. Jan/Feb 1997: 11.

http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs12/BD1997-V04-N01.pdf (accessed 24 August 2015).

8 “45 Senior Military Officers Retire to Contest Nov. 8 Poll”. The Irrawaddy. 11 August 2015. http://www.irrawaddy.org/burma/45-senior-military-officers-retire-to-contest-nov-8-poll.html (accessed 14 August 2015).

9 Reuters. “Unpopular but defiant, Myanmar ruling party unfazed about poll prospects”. 25 May 2015. http://uk.reuters.com/article/2015/05/25/uk-myanmar-politics-usdp-idUKKBN0OA1GI20150525 (accessed 14 August 2015).

10 RJ Vogt . “In Magwe, flood relief gets political for NLD”. Myanmar Times. 13 August 2015. http://www.mmtimes.com/index.php/national-news/15966-in-magwe-flood-relief-gets-political-for-nld.html (accessed 14 August 2015).

11 Nicholas Farrelly. “Myanmar and the politics of disaster”.

New Mandala. 12 August 2015. http://asiapacific.anu.edu.au/newmandala/2015/08/12/myanmar-and-the- politics-of-disaster/ (accessed 14 August 2015).

12 Derek Tonkin. “The 1990 Elections in Myanmar: Broken Promises or a Failure of Communication?” Contemporary Southeast Asia: A Journal of International and Strategic Affairs. Vol. 29 (1): 2007, pp. 33-54.

13 Timothy Simonson. “The taming of the NLD… by the NLD”. New Mandala. 12 August 2015. http://asiapacific.anu.edu.au/newmandala/2015/08/12/the-taming-of-the-nld-by-the-nld/ (accessed on 14 August 2015).

14 See Marie Lall, Nwe Nwe San, Theint Theint Myat and Yin Nyein Aye. Myanmar’s Ethnic Parties and the 2015 Elections. Location unspecified: International Management Group, 2015. http://www.networkmyanmar.org/images/stories/PDF19/Lall-MEP.pdf (accessed 24 August 2015).

15 Ibid. See page 25, footnote 18 for the list of alliances and their corresponding members.

16 Paul Keenan. “Ethnic Political Alliances”. Briefing Paper No.18. Burma Centre for Ethnic Studies Peace and Reconciliation, 2013.

http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs16/BCES-BP-18-Ethnic_Political_Alliances-en.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2015).

17 Ei Ei Toe Lwin. NLD snubs prominent politicians, activists – and ethnic alliance offer. Myanmar Times. 3 August 2015. http://www.mmtimes.com/index.php/national-news/15792-nld-snubs-prominent-politicians- activists-and-ethnic-alliance-offer.html (accessed on 24 August 2015).

18 Andrew McLeod. “Viewpoint: Aung San Suu Kyi still in running for Myanmar presidency”. BBC News. 10 July 2015. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-33476250 (accessed 2 August 2015).

19 The Irrawaddy. “NLD Patron Tin Oo: ‘I Have Never Wanted to be President’”. 16 July 2015. http://www.irrawaddy.org/interview/nld-patron-tin-oo-i-have-never-wanted-to-be-president.html (accessed on 10 August 2015).

20 Tun Tun. “NLD Says It Intends to Field a Presidential Candidate”. The Irrawaddy. 13 July 2015. http://www.irrawaddy.org/burma/nld-says-it-intends-to-field-a-presidential-candidate.html (accessed on 10 August 2015).

21 Nyein Ko and Htet Shine. “Myanmar expatriates among 32 million eligible voters”. Myanmar Eleven. 23 July 2015. http://www.nationmultimedia.com/breakingnews/Myanmar-expatriates-among-32-million-eligible-vote- 30265069.html (accessed 12 August 2015).

22 Lun Min Mang. “Voters to get identity cards”. Myanmar Times. 6 August 2015. http://www.mmtimes.com/index.php/national-news/15849-voters-to-get-identity-cards.html (accessed 12 August 2015).

23 Jonah Fisher. “Myanmar’s strongman gives rare BBC interview”. BBC News. 20 July 2015. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-33587800 (accessed 12 August 2015).