Afghanistan Counterinsurgency: The RIP/TOA Blues – OpEd

By James Emery

United States Counterinsurgency Operations (COIN) in Afghanistan and Iraq were significantly hampered by the haphazard manner in which the United States military deploys units to combat zones.

Replacement in Place/Transfer of Authority (RIP/TOA) is the process of the outgoing military unit in a respective Area of Operations (AO) transferring the authority and responsibility of that AO to the incoming military unit. Typically, there is very limited time for the respective components of the outgoing unit to transfer their knowledge, experience, and contacts to their incoming replacements. Additionally, the departing unit typically takes their files and reports with them when they leave.

It takes months for a new unit to learn enough about the districts and people in their AO to achieve an understanding of the core issues, positive and negative influencers, insurgent and criminal activity, and other key elements. The flawed policy of respective United States (US) military units being alternately sent to both Afghanistan and Iraq during multiple deployments, failed to acknowledge the fact that these were totally different Theaters of Operation. US mission objectives were further hindered by not sending units back to the respective AO they had previously worked in, significantly undermining the efficiency and effectiveness of military operations and stabilization efforts.

The history, geography, demographics, and insurgencies in Afghanistan and Iraq were very different, with additional variations and drivers within these two countries. If multiple deployments are in play, individual military units should return to the country of their prior deployment, preferably to the same AO, or at the least, one that is contiguous to it.

The negative impact of marginalized deployments and the RIP/TOA effect could have been significantly reduced by following core policies for successful counterinsurgency operations (COIN). This starts by having the priorities established by competent people who are experienced, knowledgeable, and skilled in counterinsurgency operations in collectivist cultures. Establishing core policies for respective counterinsurgency operations requires a group effort to maximize effectiveness and eliminate blind spots.

Afghanistan and Iraq are completely different countries, and the distinctions within them are substantially different – from the Pashtun, Tajik, Uzbek, Hazara regions in Afghanistan to Shia’, Sunni, Kurd regions of Iraq, in addition to numerous other factors.

Regardless of the number of rotations over a twenty year period, military units have to virtually start fresh each time, due to significant differences in the human and physical terrain in their new AOs. This includes variations in ethnic, tribal, and other demographic factors, mountain topography that affects ground and air operations, the specific people and groups that a unit has to engage, and many other factors.

There is much to learn about the players and population in the respective AO that a military unit is assigned to. In Afghanistan, this included the competency, effectiveness, and corruption levels of Government of Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (GIRoA) officials and the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF), which included the Afghan National Army (ANA), Afghan National Police (ANP), and other units. There are units from other countries with the International Security and Assistance Force (ISAF) that operate in the respective AOs, along with international and local Nongovernmental Organizations (NGOs), and a variety of other indigenous and international organizations, groups, and individuals.

There are numerous Afghan government and military officials, positive and negative influencers, powerbrokers, contractors, hundreds of elders in villages and towns, and many other individuals and groups to meet, assess, and deal with in each province. The new military unit sets up Key Leader Engagements (KLEs) and other meetings with many individuals and groups, requiring planning, travel, and time. With the exception of Ramazan (the month of fasting called Ramadan in most of the Islamic world), engagements should not be rushed or handled with a Western mindset.

Building the essential relationships takes time, some of which is allocated to nonstrategic topics that establish rapport and credibility. A solid foundation is essential to move the relationship forward to achieve the desired level of cooperation and support. This will usually require multiple encounters before proper assessments and meaningful relationships can be established.

The AO typically includes several provinces, with each province containing multiple districts and hundreds of towns and villages. The new military unit will be engaging GIRoA and ANSF officials and other players at multiple levels. They will also be dealing with powerbrokers, elders, and others in the cities, towns, and villages in their AO.

This is why it takes the first few months of a new unit’s deployment to gain a remedial understanding of all the districts, people, and issues in their AO. The first two or three months pass quickly, due to the travel required for most of these meetings, the number of people that need to be engaged, and the number of times this has to be done with key individuals to achieve a base level of connectivity that will enhance operations. There are also security issues when planning KLEs and other engagements, in addition to ongoing security operations and patrols within the respective AO.

In addition to all of this – and much more – there are also a variety of insurgent and criminal cells operating in the AO, which the new US military unit has to become familiar with, including their specific operations, criminal activities, and their links and relationships to other players and groups within and beyond the AO, including GIRoA and ANSF officials. If the AO has significant opium cultivation or narcotics activity, it creates additional issues.

It’s also important to know the links between corrupt Afghan officials at the national, provincial, and district levels. US and ISAF officials occasionally made appeals to high-ranking GIRoA and ANSF officials about the corruption and criminal activities of other Afghan officials, without realizing that the unsavory characters they were complaining about were giving a cut of their illicit income to the man they’re talking to.

In many cases, President Hamid Karzai and other high-ranking Afghan officials knowingly appointed corrupt officials to positions based upon their capacity to maximize profits from corruption, bribes, extortion, theft, narcotics trafficking, and other illegal activities in their respective area of influence and control. Karzai and other Afghan officials who appointed crooks to various positions got a share of their illicit income. US and ISAF military bases, development projects, banking facilities, and GIRoA and ANSF programs were especially targeted by corrupt Afghan officials, who stole billions of US dollars, including US $1 billion in the Kabul Bank scandal, alone.

It’s important to know the relationships when fighting or funding wars, especially when there are high levels of foreign aid, corruption, criminal activity, and narcotics trafficking. The primary export of Afghanistan during two decades of US and ISAF stabilization efforts was cash. Pallets of suitcases, stuffed with stolen US $100 bills were regularly shipped out of Afghan airports to banks in Dubai, UAE and other locations by corrupt Afghan officials and their cronies.

Implicit Knowledge and Skill

It takes time, skill, integrity, and intent to gain the implicit knowledge that will enable spontaneous, seamless comprehension and responses to individuals, issues, and events. The level of knowledge and skill must be significant to grasp the subtleties that could require a different action or response to multiple situations that look the same to people with less relevant knowledge, experience, or skill.

Applying the same rote response to what may appear to be similar situations and encounters can generate mixed or negative results if the observer cannot identify and distinguish the subtleties that make each one unique – including the specific people and relationships involved – requiring a different action or response. It would be like a physician administering the same treatment to every patient that had a stomach ailment, without knowing the specific causes or details of each person’s afflictions – from a spicy meal to cancer.

The capacity to consistently identify, comprehend, assess, and respond to varying situations when dealing with the indigenous population, positive and negative influencers, village elders, Afghan government and military officials, criminals and the insurgency will reap significant rewards, exponentially. The ramifications and benefits of quality assessments and actions go well beyond the individual encounters and events – on multiple levels. Unfortunately, so do the mistakes.

Overcoming the Flaws of Prior Deployed Units

One of the problems that deploying units must deal with is having to overcome the negative actions of some prior deployed units. This goes beyond the overly aggressive or culturally obtuse behavior of a few individuals or patrols, to include individuals and units that give out too much aid and resources without accountability or who promised jobs, aid, or other resources and projects, without following through.

Some resources, jobs, and assistance may not have been promised within the Western perspective, but by pulling out their notebooks, asking Afghan villagers what they need, and writing it down or collecting their previously requested submissions, it can convey a promise of goods or services to be delivered. This can occur, even when Western military and civilian representatives state they will submit the requests or see what can be done, without promising anything.

Communication on these issues must be direct within the respective cultural framework so that it is understood. Western officials should stress that their questions are for the purpose of information, not the guarantee of goods or services to be delivered.

If the visiting Westerner tells the village elders or other locals that they will look into their requests – from a tube well and jobs to various goods and services, this will often be elevated to the expectation of fulfillment. This goes beyond cultural misunderstandings to include deliberate manipulation by the locals. That’s why it is important to ensure clarification with verbal acknowledgements from the Afghan officials, elders, and others who are present. Failure to do that gives manipulators an opening they can exploit.

Many children on the streets of Kabul and other Afghan cities try to elicit a promise or commitment from the passing Westerner who just told them they were not interested in whatever the kid was selling or trying to obtain. Many of the kids will immediately come back with, “Next time you buy or next time you give. You promise, you promise.” Some Afghan adults use the same methods.

While a Westerner may carelessly agree, just to get away from the street urchins, Afghan children and adults will consider it a contract that they cleverly elicited. They’ll expect to collect on it the next time they see that Westerner. This could be within a few minutes when the Westerner steps out of the store he ducked in to or it could be months later.

During the 1980s, the Afghan kids living in refugee camps in Pakistani used to ask visitors for ink pens, which they would use or sell. Of course, Afghan refugees in Pakistan were existing on meager rations, inadequate housing, and limited prospects, so visitors to the camps provided entertainment and opportunities.

This behavior is not unique to Afghans, it’s occurred around the world for generations, to varying degrees. Anyone visiting tourist, entertainment, or shopping areas anywhere in the world has likely run into aggressive hawkers and touts, trying to get them into a store, into a cab, or into a compromising situation.

Three Month Learning Curve

It can take two to three months to achieve a basic understanding of a new AO and its players, factoring multiple encounters to develop relationships and obtain valuable insight on the effectiveness of GIRoA and ANSF officials, corruption, negative influencers, criminal activity, and insurgency operations. Some of the best contacts are people with the knowledge to provide vital information and background on individuals, relationships, situations, issues, and events.

When military and civilian units deploy with relevant training for their respective Theater (Afghanistan, Iraq, et cetera), along with elevated cultural knowledge, confidence, and commitment, they will be primed for assimilation. It takes time, skill, and contacts to facilitate peeling off the layers of initial assumptions, assessments, and experiences to get to the deeper levels of awareness and understanding that provide deployed individuals and units with an enhanced level of effectiveness.

During deployments, subconscious minds process everything, potentially creating a reservoir of implicit understanding, confidence, and skill that can substantially elevate performance and results. To effectively sustain and capitalize upon this process, units need to rotate back to the same Theater of Operations, preferably, to the same AO they previously occupied. This provides significant benefits to the respective troops, indigenous populations and forces in their AO, and the mission.

Good relationships with respected powerbrokers are essential in Afghanistan and most collectivist cultures. Their support can encourage many people to cooperate or assist the powerbroker’s Western friends, even when these individuals oppose the action or have no interest in it. The nature of relationships in these cultures is to comply with the requests or suggestions from powerbrokers, to remain in good standing so they can appeal to the powerbroker when they need their intervention or a favor.

Learning about the assigned AO and its players, issues, and drivers is ongoing. This will continue throughout the deployment, as US military and civilian units become more effective, deepening and expanding their local contacts and networks. As Western forces become more knowledgebase, confident, and relaxed in their interactions with Afghans, they’ll gain significant additional benefits that most of them will be unaware of.

Cross-Cultural and Nonverbal Benefits

The positive quality and subtleties of skilled, confident Westerner’s nonverbal communication – which includes facial expressions, gestures, body language, and paralanguage – will greatly enhance their credibility, likeability, and the trust and cooperation they’ll garner from Afghans – at all levels – from high ranking officials to local farmers.

The subconscious mind takes in everything, impacting how people feel about the person they are interacting with, during the engagement and long after it has taken place. Collectivist cultures are much better at reading nonverbal cues – and concealing their own – then the individualistic cultures of North America, Europe (especially northern), Australia, and New Zealand. This is especially important in war zones, where proper assessments can have life and death consequences. This is made more important and complex by the number and variety of Westerners the Afghans dealt during the twenty year conflict.

The quality, depth, and speed of knowledge gained and lessons learned will vary significantly between respective military and civilian units, depending upon their attitude, training, experience, and the length of their deployment. Obtuse fools and arrogant thugs insult and abuse Afghans, in a country where personal honor plays such an important role. The caustic, intimidating, and disrespectful behavior towards Afghans by some deployed individuals and units is a detriment to the mission and to others working that AO, as well as the units who deploy to the AO after they’ve left.

The benefits of enhanced cross-cultural and nonverbal skills honed in conflict areas are transferable to other locations and careers. It is advantageous for an individual to know what the people they are dealing with think, how they process information, and how they are likely to react in a variety of situations. This applies to law enforcement, teachers, sales reps, counselors and virtually every other profession, to varying degrees.

Arrogant Thugs and Obtuse Fools

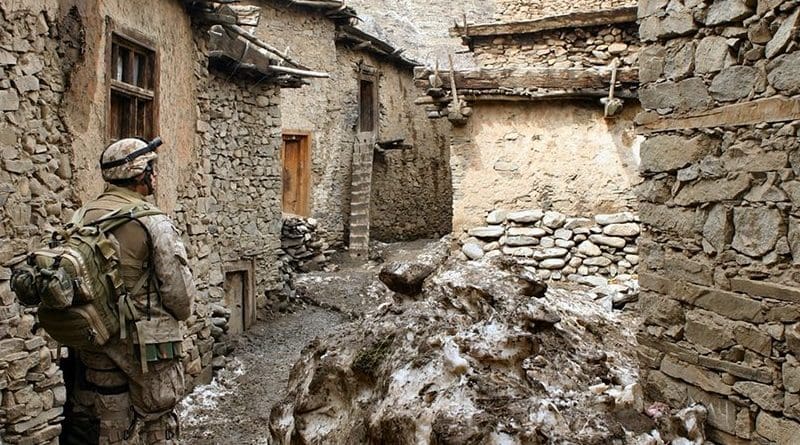

If some US or ISAF patrols in an AO become overly aggressive, insulting, and thug-like towards Afghan civilians, all of the other patrols in the respective area – from that point onward – may become targets for IEDs (Improvised Explosive Device), RPGs (Rocket Propelled Grenades), and other attacks. These will be carried out by insurgents, often with the help of the person who was abused, or one of their friends or relatives. Additionally, US and ISAF bases in the area will likely see an increase in mortar and rocket attacks.

A thug mentality among US and ISAF units patrolling the roads or visiting villages and towns is detrimental to stabilization efforts. If the US or ISAF officer in charge of these patrols is arrogant, obtuse, and aggressive, they’ll encourage a thug mentality among their troops. This can also be initiated from within the ranks, but encouraged, tolerated, or ignored by the officers. Transgressions can include aggressive driving, stomping on the car hoods of Afghan civilians for no reason, while pointing automatic weapons at the traumatized families in the cars, insulting and intimidating elders and locals during visits to villages and towns, and other repugnant behavior.

Fortunately, most of the deployed US and ISAF soldiers and civilians represented themselves and their countries in honorable ways, while striving to build good relationships and understanding with their Afghan counterparts and the local population. However, I’ve seen the dark side, as well, when a specific commander or patrols were spun up, aggressive, abusive, and insulting. Some of these patrols would occasionally stop and dismount to carry out intimidating foot patrols in villages and towns, to the detriment of local Afghans they abused, insulted, or argued with, and to all the other US and ISAF units operating in that area, from that point onward.

One deranged US Intel officer on a US base in Afghanistan, grew his narrow sideburns to meet his Van Dyke style beard, keeping the other areas of his face shaved. This was a strange looking beard in Afghanistan, where beards are full on the men growing them. This Intel operative went around the base telling people that he grew his bead in this unique style so Afghan villagers would be afraid of him, thinking that he was CIA (US Central Intelligence Agency) or Mossad (Israeli Intelligence Agency), and that he might kill them. He mistakenly felt he could get information by intimidating Afghan civilians.

This is a true story. He was not joking. What’s worse is the fact that this arrogant, threatening, and deranged officer was in charge of the military unit’s Intel Operations, with a focus on engaging the Afghan population. He and his team of thugs created problems for people on both sides of the wire, during his deployment.

Fortunately, overly aggressive patrols and deranged characters were the exception, but one to too many, and there were a lot more than one. This sordid behavior was responsible for getting other US, ISAF, and ANSF soldiers and civilians killed or maimed. These type of abusive and aggressive soldiers and civilians are best suited for permanent garrison duty at bases in the United States.

Allowing these type of abusive individuals to deploy is detrimental to missions, even if they never leave the base. Most bases have a significant number of locals working on them, who these toxic tyrants will insult and intimidate, diminishing local support for the US mission and encouraging some of those abused to join or assist the insurgency.

Additionally, having overly aggressive and prejudiced thugs in the ranks can negatively influence the beliefs and behavior of other deployed personnel, undermining their interactions with locals through their inappropriate behavior and negative nonverbal leaks that will resonate with the locals at the conscious and subconscious level.

Length of Deployments

Generally, with minor exceptions, US Army units deployed for a year, with a range of nine to fifteen months. Air Force Units did six months and the Marines did seven months. Factoring that it takes at least two months to gain a basic understanding of their AO and the last month is focused on RIP/TOA, leaves very little time for effective interactions and operations to secure and stabilize an AO from the external threats of insurgents and criminals and the internal threats of corruption and abuse by some GIRoA and ANSF officials, powerbrokers, contractors, and others.

Operating within the collectivist cultures of Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, requires multiple engagements with people to establish meaningful friendships, within the scope of their cultural parameters, not Western ones. This takes time and effort. It requires a positive attitude, because negative thoughts about the people will generate negative nonverbal leaks. The conscious minds of their audience will detect some of these, but their subconscious will absorb all of it, impacting what they think about the Westerners they’re dealing with. This will influence their levels of cooperation and support.

Building strong relationships – at the deeper levels of trust and cooperation that are needed in conflict areas – is a process that cannot be rushed. Some units and individuals try shortcuts, using bully-boy intimidation, which can cause people to switch their support to the insurgency. Other units tried to win local support by providing money, projects, and resources to people who may lack the integrity or capacity to properly utilize or distribute them as they were directed.

Local officials, powerbrokers, and others will take the resources Westerners offer, which can “rent” their temporary, conditional support, but it lacks the implicit, culturally defined fiber that will provide more meaningful information, assistance, and loyalty at the depths required for effective counterinsurgency operations and sustainable stability efforts. In some cases, specific US aid programs were reduced or eliminated, because they were temporary, ineffective, or the Afghan’s administering them are stealing or selling most of the aid they are supposed to be freely distributing to the population. When programs are curtailed, some Afghan administrators became surly and less cooperative.

For newly deployed US forces to achieve an advanced capacity of comprehension and an acceptable level of effectiveness throughout all the units operating within their respective AO, takes a long time. Some units will achieve this heightened, implicit sense of awareness and skill, but they’ll rotate out a couple months later, taking all of their valuable knowledge and experience with them.

Afghan government and military officials, village elders, contractors, and the Taliban know that the United States chose to fight two decades of a sequential series of semiautonomous, six to twelve month wars in smaller AOs throughout the country. Effective US and ISAF units operating in specific areas of their AO may be followed by overly aggressive units that are spun up or by culturally-obtuse, apathetic units, who operated like tourists – just passing through.

US RIP/TOA Policies were Stressful to Afghans

In collectivist countries like Afghanistan, meaningful relationships and implicit understanding is important, so having the units come back to their previous AOs will resonate positively with most GIRoA and ANSF officials, powerbrokers, contractors, village elders, and others in their AO. This is especially important in conflict areas.

To effectively work in these collectivist cultures, military and civilian units are encouraged to focus on group dynamics and key relationships, establishing essential support and a similarity of purpose to achieve sustainable mission objectives, with continuity provided by rotating units returning to their previous AOs.

Haphazard US rotations that repeatedly throw units into a new AO, require all of the Afghans in the AO to continually assess the capacity and skills of each new unit and their respective commander, officers, soldiers, civilians, and support groups. They will have to establish new relationships, monitor the new units’ actions and mistakes, and occasionally provide some knowledge and insight within an Afghan cultural context, usually with a focus of educating without offending or leaving themselves vulnerable, if the sensitive information they provide is mishandled by the Westerner.

Imagine having to do this with all of the primary and secondary units rotating into the AO over a 20 year period. This was stressful and frustrating for Afghans who were working to strengthen and defend their community and their country. This was especially traumatic for individual Afghans and groups who established meaningful and effective working relationships with units, only to have to deal with new individuals with diminished knowledge, challenging personalities, or significant changes in their priorities and approach to the AO.

There are many distinct military and civilian units operating within each AO. Overly aggressive, culturally obtuse, or operationally deficient military and civilian units and patrols can undo the good relationships and stability efforts accomplished by their predecessors and by other competent units operating in the respective AO. In addition to the detrimental impact upon these Afghans and specific sections of the AO, it can make it more difficult and time consuming for future units to gain the level of trust and cooperation they’ll need to be successful, further diminishing the short period of optimal rotational effectiveness.

The Afghan Shell Game

Relief in Place/Transfer of Authority (RIP/TOA) in which outgoing US military units transferred responsibility for their respective Area of Operations (AO) to the incoming unit, was a celebratory event for corrupt GIRoA and ANSF officials, negative influencers, criminal groups, and the insurgents. The outgoing military unit that had wised up to the unsavory antics of Afghan incorrigibles in their AO would be replaced by a new unit that could be deceived, stalled, and ignored, providing corrupt officials and criminal groups with a reset button for each new deployment.

Corrupt and criminal Afghan elements would engage and evaluate the naive incoming units the way seasoned, street hustlers around the world measure the vulnerability of potential “marks” frequenting tourist and entertainment areas.

President Hamid Karzai and other officials – at all levels – played the game that had become common among corrupt officials and negative influencers throughout Afghanistan, stall US officials until they rotate out, and deal with their replacements. Even if the new unit had experience in other parts of Afghanistan, and had read some of the previous unit’s reports on the AO, they would lack implicit knowledge of the deeper aspects of their new AO and the people within it.

The typical stages of dealing with corrupt officials often began with them flattering their Western counterparts. A few tried intimidation. Both scenarios would be followed by denials and indignation over accusations made about their corruption or incompetence. Agreements would be repeatedly made and ignored or broken for several months, which deteriorated into a stalemate that continued through the RIP/TOA. Corrupt officials hit the reset button when the unit departed. They continued to repeat the process with each new unit, while lavishly enriching themselves and their cronies through corruption, theft, and extortion, until all of the Americans finally left in 2021.

Sometimes, naive or willfully obtuse US and ISAF military and government officials would simply ignore the corruption and crimes to avoid controversy that could raise concerns further up the chain-of-command. Some US military and civilian bureaucrats submitted exaggerated or overly optimistic reports, along with selective omissions. It was known or assumed that revealing serious problems and ongoing issues and concerns to some of the people higher up the military and government chain-of-command could generate negative blowback that could be detrimental to careers.

There’s the rub. It’s risky to one’s career to point out that the lush oasis of agreements and accomplishments that top US officials are celebrating as an example of their success in managing the Afghan mission is actually a mirage, concealing a dessert wasteland, strewn with corruption, deceit, and incompetence that is empowering insurgents and losing the support of the population.

Arrogant, abusive officials, like US Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld, could be especially vicious when his statements, lies, and deceptions were countered by ethical US military officers and government officials, who told the truth about ongoing issues in Afghanistan and Iraq.

As a result, some military and government leaders, directing the Afghan and Iraq wars from the United States or from the respective Theaters, surrounded themselves with ideologues and incompetent, unknowing, or unethical staff members, who dutifully supported false narratives and lies regarding the capacity of indigenous security forces and government officials, support of indigenous populations, and the status of the wars. It’s reminiscent of the US War in Vietnam, where the body counts being reported made it appear that the US had killed every communist in Vietnam.

Tasking Military Commanders

A US military officer in Afghanistan was advised that the 300 temporary jobs he was going to give to the sub-governor of the province to equitably and freely distribute among the population were being sold by the sub-governor for US $200 each – in advance – netting him US $60,000. Some desperate Afghans took out loans so they could “buy” a job that was supposed to be given to them for free. The military commander was advised of the price being charged and the total sum being extorted.

The commander’s response was, “Corruption is a problem in Afghanistan, but it’s better to deal with the devil you know, than the unknown.” Nothing was done to investigate, deter, or punish the crooked sub-governor, whose cooperation was deemed necessary in other matters.

There are several things to consider with this example. Extortion and theft permeated all levels of Afghanistan. This is a just one small example. The commander in this case was a highly competent and effective military officer for the primary duties he was responsible for within the respective AO. He had significant responsibilities for security and other issues in the AO. The 300 jobs was a minor side request for a military officer whose focus was on security and patrols in a hostile environment.

US military officers are reluctant to make waves because some military and civilian officials further up the chain-of-command, discouraged debates over Afghan corruption and accountability. US officials trying to reduce corruption could find themselves blamed for stirring up problems. Additionally, challenging corrupt Afghan officials and submitting the reports through the chain-of-command, can diminish plausible deniability of US officials who distort reality to promote false narratives of a failing war.

These type of situations of ongoing corruption and theft being tolerated or ignored by US and ISAF officials occurred throughout Afghanistan for the duration of the US occupation. This gets back to the need to have skilled, experienced people establish the guidelines and priorities for the respective missions in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Corruption and incompetence by local officials is fatal to counterinsurgency operations, making it more likely that indigenous government and security forces will collapse when US forces are withdrawn. Rank and file government officials and soldiers were aware of the extensive corruption taking place among high ranking officials, who liquidated and moved their assets out of Afghanistan to facilitate their departure after the US announced it was ending all military operations in Afghanistan

While there were US military Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs) and other military, governmental, and civilian organizations operating in Afghanistan, virtually all of them shared similar issues and time constraints that undermined their effectiveness. The PRTs should have been sharing and returning to specific AOs. This would have enabled them to know what specific projects should cost in their AO and the best contractors to use, in addition to having the continuity to initiate long-term projects.

Were Lessons Learned?

The fact that the handling of troop rotations, the impact of corruption, and so many other core facets of effective counterinsurgency operations were ignored, indicates the emphasis was not on stabilizing Afghanistan and winning the war, but upon perpetuating it – by design or default. US policies enriched corrupt Afghan government and military officials, whose actions continually undermined counterinsurgency operations. Flawed US policies and corrupt Afghan officials made defeat inevitable.

The winners of the 20 year Afghan war and occupation were corrupt Afghan officials, the Taliban – who extorted millions of US dollars from development projects, in addition to winning the war, and the US Military Industrial Complex (MIC).

US Defense budgets soared and the US MIC enjoyed two decades of exorbitant profits. Additional profits by Halliburton and other MIC firms were obtained through unethical price gouging on essential US military services and supplies. The US government borrowed the money to fund the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, significantly increasing the massive US deficit.

While many US government, military, and intelligence operations are well managed, some are run by marginally competent to incompetent bureaucrats or ideologues, who manipulated their way into a position of power or floated up through the ranks. This includes some who determine or influence rotation schedules, deployment locations, and numerous other facets of military operations, without knowing what factors are important – and why.

Knowing the “why” is vital, because it enables individuals to accurately fine-tune their response to variable and changing situations and terrain. This enables them to provide accurate assessments and appropriate reactions, regardless of internal and external variations and drivers that change the scope and details of the mission within the respective Theater of Operation and Areas of Operation.

Unfortunately, while some of these administrators attempt to address these complex issues, others – including high ranking officials – lack the capacity or motivation to do so. Some are also influenced by conflicting drivers that undermine mission objectives, including meddlesome to detrimental intrusions and dictates from people further up the chain-of-command.

The ongoing disconnect and apathy from some top US government and military officials to rank-and-file facilitators created serious problems in Afghanistan and Iraq. Implementing effective military deployments, counterinsurgency operations, development programs, and all of the supporting activities, equipment, and supplies, requires that the individuals overseeing these efforts have relevant knowledge, experience, and skill – along with the core traits of integrity, aptitude, and motivation – to do their jobs at the required level of effectiveness.

The objective should be to ensure that US and allied military and civilian units are provided with the resources, deployment policies, rules of engagement, and objectives that will maximize their effectiveness and the success of their missions. Many US government and military officials failed to do this, which is why deployments foolishly rotated military units between Afghanistan and Iraq as if they were the same war simply because both countries were Islamic. They failed to consider that the history, issues, populations, and wars within these two countries were significantly different.

More importantly, they failed to grasp how important it is to have deployed units share an AO over several rotations in order to maintain the desired levels of knowledge, experience, relationships, planning, and accountability that are essential to successful counterinsurgency operations and other conflicts.

The absurdity of assuming that military campaigns waged in two different countries are the same because they share a common religion is as flawed as assuming Western companies can use the same marketing campaigns for a variety of consumer products in England, Saudi Arabia, and Japan, because they all drink tea.

This failure to know – or care – about the characteristics, distinctions, and differences between and within Afghanistan and Iraq is why the Pentagon spent US $28 million on forest green camouflage uniforms for the Afghan army. Had they reviewed any of the readily available public resources, they could have read that only about 2 percent of Afghanistan was covered by forests. If they contacted people who knew about Afghanistan, they would have known that only about 1.5 percent of Afghanistan was wooded at the time of their inquiry, due to extensive deforestation in recent years.

Most of Afghanistan is brown, tan, and barren, comprised of rugged, desolate mountains, flat plains, and desserts. The green camouflage uniforms given to the Afghan National Army (ANA) put them at risk. All the Taliban had to do was aim for the “Green ANA bushes” that would stand out against the barren, brown and tan terrain. The fact that uniform orders can be screwed up this badly sheds light on how poorly all other aspects of the war were implemented.

Similar mistakes were made in burdening US civilians and soldiers deploying to Afghanistan or Iraq with multiple duffle bags worth of equipment, much of which was excessive or ill-suited for their location and assignment. Of course, much of this was likely driven more by the shenanigans surrounding military suppliers, the acquisition process, and the unsavory quid pro quo incentives used by suppliers to gain access and distribution.

DEA FAST Teams

The US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) embraced the shared AO rotational concept with their Foreign-Deployed Advisory and Support Teams (FAST) that were operational in Afghanistan. The DEA FAST team unit preparing to deploy was in touch with the DEA unit in Afghanistan they would replace. Additionally, the DEA units in the US that were providing support to the respective deployed DEA FAST TEAMS would have previously worked in that AO. Their implicit knowledge of the AO and the players and issues enabled support teams to provide fast and fluid assistance and resources that matched the needs of the respective AO.

The deployed DEA FAST team stayed in touch with the unit it replaced, maintaining a continuity of information and tactics. This is the way to run deployments, striving for excellence through the character and capacity of personnel and the ongoing sharing of information and objectives to maximize results, eliminate blind spots, and achieve sustainable success. These DEA FAST teams shared accountability of training, projects, and operations through a collective focus on mission objectives.

US military deployments had to deal with the fact that some projects and operations required longer periods of time to implement, which can create issues with replacement units that have their own perceptions and priorities regarding projects and operations. The cohesive methodology of DEA FAST team deployments helped establish mutually agreed upon objectives, facilitating their attainment.

Their Afghan counterparts experienced a continuity of operations, relationships, policies, and accountability with the respective rotating DEA FAST teams, enhancing their confidence, capacity, and effectiveness. This is the way to operate to maximize results. The DEA was instrumental in the success of Afghan counternarcotics efforts through the Afghan National Interdiction Unit (NIU) and the Sensitive Investigation Unit (SIU), components of the Counter Narcotics Police of Afghanistan (CNP-A).

I’ve investigated narcotics trafficking in Afghanistan, Burma, and other source and transit countries for over thirty-five years. I am familiar with all facets of narcotics trafficking in Afghanistan – from source to street – including networks and distribution routes that distributed Afghan heroin into other countries.

When the Taliban initially took control of Afghanistan, many of the heroin processing labs in Pakistan moved across the border into Afghanistan, where they were protected. The DEA trained Afghan teams became so effective at destroying heroin refining operations in eastern Afghanistan that many heroin labs fled back across the border to Pakistan to escape the highly motivated and effective Afghan units trained by the DEA.

The DEA operated as a series of connected teams, within the collectivist culture of Afghanistan. DEA had to deal with illiteracy issues within CNP-A units, along with their initial failure to seize and secure cell phones and evidence from raids, and other issues, but their teams worked together to create successful counternarcotics units.

The quality and competency of DEA personnel, combined with the collective laser-like focus on the key objectives and best methods, facilitated their success. The US military and government could learn from these examples, structuring and deploying military troops and government employees and contractors with similar templates.

Counterinsurgency (COIN) 101

To achieve sustainable success, US government and military units need to establish and obtain meaningful mission objectives that address corruption, competency, and effectiveness of local officials, with the same enhanced focus they use to pursue insurgents and terrorists.

Counterinsurgency is much more than military effectiveness. The key to COIN is that the indigenous government and security forces must have the support of the population to be successful. The most significant issues that plagued Afghanistan were the corruption and incompetence of officials, coupled with their abuse and fleecing of the population. It was virtually impossible for the US and ISAF to achieve success in Afghanistan when the ongoing flaws of GIRoA and the ANSF were ignored. Continuing to funnel troops and resources into Afghanistan without addressing the core issues was as predictable and foolish as using a bottomless bucket to scoop and carry water.

In the group-oriented, collectivist cultures of Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, it is essential to develop and maintain personal relationships to effectively counter insurgencies and criminal groups, reduce corruption, facilitate development efforts, and garner the quality of information and support that are essential to understanding the respective AO, and everyone operating within it, on all sides of the war.

Regardless of what else a military or civilian unit accomplishes – otherwise – it will be significantly diminished and less sustainable if they have failed to develop and maintain meaningful relationships with core players, powerbrokers, and information sources within their respective AO. Going through the motions can make for compelling reports, but these fictional or exaggerated accounts will never resonate with the indigenous population, nor will they achieve mission objectives, assuming the unit has any that are relevant and quantifiable.

Establishing a flexible rotation schedule where a number of units are assigned to share an AO on a rotating basis, while keeping in contact with each other – before and after rotations – greatly facilitates effective COIN. This approach encourages the sharing of information, establishment and attainment of short- and long-term projects and goals, accountability for performance, and achieving essential mission objectives.

Incoming units, knowledgeable of the human and physical terrain and kept informed through the reports of the current and previous units, can be highly effective and efficient each day of their deployment. The enhanced, supportive nature of rotating units will be better able to reduce corruption, crime, and the insurgency.

While military units will have multiple personnel changes between deployments, the core group will remain, providing a continuity of knowledge, capacity, effectiveness, and relationships that will be shared with those who join the unit. This can make them highly effective from the moment they deploy and throughout their tour of duty. It will help keep the troops and civilians safe and the missions successful.

Military and civilian units will be more motivated about going back to their previous AOs. They’ll look forward to engaging the local friends they made during their prior deployment. They will be better able to deal with negative influencers and issues. Their prior experience and lessons learned can be directly applied to the same people and situations they dealt with before.

This creates numerous exciting opportunities for the deployed unit to raise the bar on their performance, systematically enhancing their effectiveness. This is the way to run successful counterinsurgency and combat operations, strengthening relationships with positive influencers and the population, while tightening the noose on the negative influencers, from corrupt officials to insurgents.

The shared AO concept can better generate sustainable stabilization efforts, creating a geographic patchwork of terrain with enhanced security and success that expands upon ink blot strategy. Problem areas can be isolated through the encroachment of stable, secure terrain. Resources can be more effectively allocated to address the remaining problem players and terrain, enhancing security by reducing corruption, crime, and insurgent activity.

Less is More

While some people criticize counterinsurgency doctrine – COIN – as being ineffective, due to the failure in Afghanistan, it’s a bit like calling the theory of flight a failure, because a man who used wax to attach feathers to his arms and then jumped off a cliff, expecting to fly, fell to his death.

The COIN doctrine works, but it has to be properly designed, managed, and implemented for the respective human and geographic terrain it is addressing. The first priority is to ensure that the indigenous government and security forces are reasonably competent, ethical, and have the support of the population. If these three essential components are lacking, the potential for success is slim. Then it’s a matter of establishing core objectives and implementing the appropriate methods and follow-through to achieve success. This requires relevant experience, skill, and commitment with quantifiable goals, a focus on objectives, and an extraction plan.

Personally, I believe, “Less is More,” when it comes to counterinsurgency operations. Inserting large scale military deployments to counter indigenous insurgencies is often the wrong course, for numerous reasons. I believe that COIN is best implemented by inserting smaller numbers of soldiers and civilians, who have the appropriate experience, skill, and core traits to make a difference.

The people deployed will be more effective and more efficient than large-scale deployments of soldiers and civilians, most of whom lack the necessary experience, skill, and aptitude for COIN operations. The distractions of massive development projects, corruption, and numerous US troops and contractors – most of whom will never go outside the wire or contribute anything of value – are removed.

Significantly smaller numbers of deployed US soldiers and civilians will attract less attention, removing the lightening rod of massive US troop deployments that encourage jihadis and their supporters from around the world to join the fight or help fund it. This can increase insurgent and terrorist activity in other countries, because when these foreign fighters return home, they’ll have increased prestige, influence, skills, and motivation. Many of them will establish or expand insurgent or terrorist cells in their own countries or the countries they move to.

Smaller deployed units of US Special Forces and similar assets can work with indigenous forces, providing the appropriate input, training, and logistical assistance with weapons and supplies. This template focuses on having the indigenous security forces take the lead in fighting the insurgency. This can make them more confident and effective, reducing or eliminating their dependence upon US troops. This approach facilitates sustainable success, as proficient and motivated indigenous security forces are unlikely to collapse and run when the small detachments of US forces leave.

Indigenous forces will be doing most of the fighting, so when it’s time to pull out the small number of US forces, the effect should be virtually imperceptible to everyone from the indigenous forces and the insurgency to adversarial states and observers. Seamless in and seamless out during insertions and extractions, with virtually imperceptible ripples on the surface during the process.

If indigenous forces are unwilling or incapable of successfully fighting the insurgency, then the US should temper their involvement in what will likely be a lost cause – except for the US MIC and the corrupt indigenous officials, who profit from it. These unsavory profits will not justify the loss of lives and limbs of US soldiers and civilians who deploy to ill-advised conflicts. Nor will it reimburse US taxpayers, who ultimately fund these flawed wars, to the detriment of a crumbling US infrastructure and a soaring US deficit.

The decision for the US to engage in specific military operations should not be driven by predatory globalists, warmongering ideologues, or the US MIC. Blindly supporting corrupt, incompetent governments or tyrannical regimes undermines the credibility and stature of the United States in the international court of public opinion. This will hinder US foreign policy initiatives and future US counterinsurgency operations – everywhere – in addition to putting US citizens and others more at risk of future attacks by terrorists and insurgents.

James Emery, a cultural anthropologist, has covered Afghanistan for over 35 years, including numerous trips into the country with the mujahideen during the Soviet occupation, in addition to scores of interviews with mujahideen political leaders, commanders, and others. He’s covered all facets of Afghan narcotics trafficking – from source to street. He worked with US, ISAF, and ANSF on both sides of the wire, in addition to conducting interviews and building relationships in Afghan villages and towns. He may be contacted at [email protected]