Demonstrations In The Arab World: Reason For Introspection – OpEd

By Jamil Toubbeh

As the sand settles on few demonstrations in the Arab world, Arab leaders and political analysts are busily assessing their long-term impact on Arab societies while their counterparts in the Western world are searching for novel approaches to maintain the status quo—the Sykes-Picot paradigm.

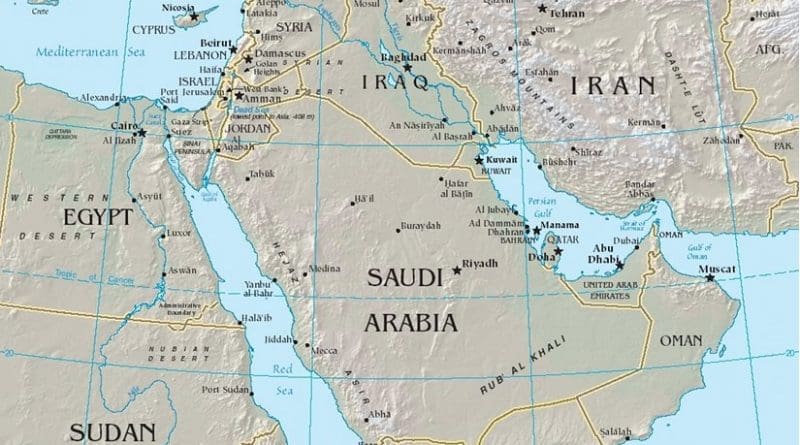

Since the end of WWI, Western nations have learned to negotiate with corrupt and iron-fisted rulers worldwide but particularly in the Arab world, leaving the Arab citizen open to repressive regimes. The Arab world has oil and now huge deposits of uranium. It has a large population (400M) that is dependent on Western technology and products, and occupies a strategic part of the globe that has been a highway for trade and warring Eastern and Western nations. Today, colonialism, in various forms, dominates the Arab world. With the exception of Israel where the concept of classical colonialism is inseparable from Zionism, neocolonialism is a more appropriate concept to apply to Western encroachment in the Arab world. Neocolonialism is akin to paternalism. Whereas neocolonialism implies political and economic hegemony, paternalism implies management or control of behavior, the common denominator being intrusion. The settler movement in Palestine/Israel fits under the heading colonialism, while the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan under neocolonialism, and Senator McCain’s appearance in eastern Libya, paternalism-in-the-interest-of-the-state. Neocolonialism in the Arab word has created the conditions that precipitated the mass demonstrations. A correlates of political and economic hegemony is security, represented by a formidable human shield to protect dictators and to facilitate the neocolonialist mission–at the expense of citizens. Mubarak was the quintessential leader-servant of colonialist Israel and neocolonialist US.

The recent and ongoing demonstrations in the Arab world have presumably caught Western and Arab leaders by surprise. The demonstrations, occurring sequentially in more than a dozen Arab nations, were generally peaceful even though in some instances challenging to unarmed civilians. Causes cited for the demonstrations vary but the predominant themes included corruption, extended emergency laws, food prices, unemployment, and freedom of speech and movement. Algerian, Egyptian, Syrian and Yemeni demonstrations drew millions of citizens. In Bahrain, the US military presence in the emirate prompted a Saudi military intervention. In Libya, US and its NATO allies intervened in behalf of the opposition, bombing strategic military targets, but civilian collateral damage and deaths were reported. The Egyptian demonstrators were successful in sending Hosni Mubarak, a US ally described as “moderate”, scurrying to Sharm el Shaikh, a Red Sea resort and a favorite kindergarten sandbox for diplomats engaged in numerous failed peace negotiators on the Israel-Palestinian six- decade old “question”. To date, the only demonstration that had an immediate positive outcome was that in Tunisia: the ouster of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali following 23 years of iron fisted rule over 11M people, exceeded by Mubarak’s 30 years of even harsher rule over 84M, and the two Assads’, Hafez and son, Bashar, 40 years over 22M people.

The demonstrations, the earliest of which starting in December of 20100, have been shadowed by Japan’s victims of catastrophic earthquakes and tsunamis, President Barak Obama’s announcement of his intention to run for a second term, an unusual spate of tornadoes, one described as a “monster tornado” in the US heartland, and lately, the lightning attack on and assassination of Osama bin Laden who, according to US intelligence sources, was the mastermind of the attack on the World Trade Center in NYC, a day remembered in the US as 9/11.

For an Arab who was born in Jerusalem, Palestine, and had lived in a country whose population was nearly 95% Muslim and Christian Arabs before the establishment of Israel, the sequential demonstrations evoke a meaning that transcends the dictionary definition of ‘demonstrations’. While it may be true that most demonstrators were demonstrating against corruption and despotic leadership, it is also true that they were demonstrating for human rights and the right to choose their governance free of foreign intervention. The latter is far more significant in the light of Arab experience under colonialism and its vestige, Israel. The right to choose includes the right to protect and manage resources, human, natural and pecuniary. During the demonstrations, no Western or Arab reporter working in behalf of Western media, or political analyst had placed the demonstrations in their historical perspectives. It is a fact that the demonstrators are the children and grand children of parents who were either born into or made subjects of colonial entities, the very entities that created the political and consequently economic environment for the type of governance that precipitated the demonstrations. One wonders if the absence of the historical context was deemed politically expedient at a time when the US and its NATO allies are engaged in military adventures that mimic or repeat déjà vu scenarios of yesteryears. Political correctness in the media is self-serving.

A Herodotus or a Toynbee observing the current state of affairs in the Arab world would describe the demonstrators as cataclysmic social, cultural and geopolitical intifadas with a potential to alter Western perception of the Arab world and Arab nations’ role in a rapidly changing technologically-focused world. While the shamans of West and East would adhere to the concept that religion should guide human behavior, history proves, again, that crusades are masks that conceal ulterior motives or actions. Wars on Iraq and Afghanistan have been justified as crusades against tyranny when, in reality, they were and still are, neocolonialist platforms to shape and control the destinies of the two nations. Iraqi’s share of the war: a devastated landscape, 1.5M deaths and untold numbers of injured, millions of refugees and a ruined society. The cost to the US alone was 33,000 casualties and a trillion dollar debt.

If Arab demonstrators had anything in common, it was (and is) liberation from all forms of tyranny, whether state, foreign, or religious extremism. The secular nature of the demonstrations was even apparent to reporters who rarely report on Arab affairs. The irony of the demonstrators’ common goal was the presence on their land, shores and in skies of the very powers that had dominated them for over century. There is no place on earth today that has more firepower around and above it than the Arab world, the epitome of that power being Israel. Senator McCain declared recently that America’s presence in Iraq will be indefinite, perhaps well beyond 2020. In Libya, he promised support for the opposition. If the opposition wins it battle, a US base in Libya would represent an extension of Western imperial power. The proverbial ‘fat lady’ has not sung yet on Western designs, but surely liberation from all forms of tyranny is on the agenda of Western strategists, however benevolent they may appear to be.

It is hard to believe that the demonstrations had caught Arab and Western leaders by surprise. The Arab world is not fantasyland; it has been and still is a war zone and a real-life testing ground for Western war technology. Palestinians have been demonstrating against colonial, repressive and apartheid regimes long before my father’s birth 1882. ‘Surprise’ is diplomatic jargon for rocking-the-boat of established relationships between Arab regimes and Western neocolonialists. The 104 acre, 26 block US embassy in Iraq and the presence of 50K US troops and an equivalent number of civilian security personnel are symbols of US intent to dominate the internal and external affairs of Iraq, including absolute control over Iraq’s natural and human resources. Control over these resources will ensure dominance over Iraq economy. Democratizing a society of 26 million under military occupation is an oxymoron. Demonstrators in Egypt have to face a US aid package that is tied, disproportionately, to US Israeli aid package. The Egyptian military is the recipient of the larger portion of the Egyptian aid package. Does this mean that the next elected president of Egypt will be guided by policies made in the US or Israel? The situation in Syria has resurrected a shelved Western plan for ridding the civilized world of “rogue nations” in tandem beginning with Iraq, followed by Syria, Iran and N. Korea, in tandem. Israel, a rogue nation shielded historically by US United Nations vetoes, has, to date been a significant beneficiary of the plan.

In a world where nations assume, by default, characteristics of their leaders and where the powerful proffer titles to rulers or nations that contradict reality, one wonders if the of the art of the incongruous has become an the jargon of modern diplomacy. In the West Mubarak was described as a moderate leader, leading a moderate nation. The Egyptian citizen thought otherwise. Bashar Assad of Syria was a Mubarak to his people and never earned the title “moderate”. What makes one dictator a Teddy Bear and another a Beelzebub in foreign affairs? When the foundations of policies rest on shaky grounds, rational answers are difficult to find. George Washington provides some clues in his Farewell Address”: [A] passionate attachment of one Nation for another provides a variety f evils… facilitating the illusion of an imaginary interest, in cases where no common interests exists; and infusing into one the enemies of the other, betrays the former to participation in the quarrels and wars of the latter, without adequate inducement… [leading] to concessions to the favorite Nation of privileges denied to others…[exciting] jealousies, ill will and a disposition to retaliate, in the parties from whom equal privileges are withheld…[giving] to ambitious, corrupted or deluded citizens (who devote themselves to the favorite Nation) facility to betray, or sacrifice the interests of their own country, without odium.”

President Obama, sir, most Arab demonstrators are unaware of Washington’s “Farewell Address” but are of their own great leaders who espoused similar principles. Deep in their hearts and mind they would embrace Washington’s principles had you made reference to them in your latest speech on the Middle East. The foreign policy speech, Mr. President, did not cut the mustard; it was déjà vu.

The Arab world is as important to its people as the US to its citizens. Is there a better way for an Arab to demonstrate his/her love to country than a bullet in the chest? Is oil more precious than a creative mind?

– Jamil Toubbeh is author of Day of the Long Night, (McFarland & Co. Publishers), a Fulbright Scholar and recipient of the Eagle Feather for work on Native American disability policy. He is currently Senior Researcher in cancer health disparities at Center for Asian Health, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA. He contributed this article to PalestineChronicle.com.