India’s Policy Of Multi-Alignment And Its National Interest And Response To War Over Ukrainian Territory – Analysis

India’s foreign policy under the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi firmly stands on the premise that it can serve the country’s national interest better not by forging military alliances with any great powers but by diversifying strategic partnerships with many countries through a policy of multi-alignment.

Besides, the country can also avoid excessive military obligations and commitments arising out of military alliances. In this light, it cringed from formally endorsing the military objectives of other QUAD members of the Indo-Pacific alliance and projected its Indo-Pacific policy to be broad enough to include Russia and other powers as well which subscribed to and could contribute to the idea and concept of free and open Indo-Pacific.

For instance, India’s Ambassador to Russia Pankaj Saran had remarked in June 2018 that expansion of ties and partnership with Russia was an integral of India’s Indo-Pacific policy. What he said during that time holds good even today and demonstrates India’s preference and penchant for multi-alignment policy. India sought to forge strategic bilateral ties with both US and Russia in the post-Cold War era despite oft-repeated criticisms that India was courting the US more and cold-shouldering its traditional patron, Russia. However, the continuing war on the Ukrainian soil contains and plays out certain dynamics that ask for a far more proactive role from India than just reacting to the evolving scenario from a multi-alignment policy thrust.

China is secretly leveraging its strategic partnership with Russia over the Ukrainian war theatre although it has publicly offered a role of a peace broker by encouraging the parties to war to end the war. On February 24, China released a position paper containing principles to arrive at a political settlement to the war between Russia and Ukraine.

In fact, China is trying to camouflage its critical military and financial support for Russia under the cover of its diplomatic outfit. Russia burdened with sanctions by the US, Europe and other American allies and without any partner which could provide it with economic and military support in explicit terms, it is increasingly relying on secret support from China for averting the regime of sanctions and for securing economic relief.

After every crisis, Russia’s relations with China assumed more prominence. For instance, following Russia’s annexation of Crimea when it was facing mounting sanctions on several fronts, China was first country to buy S-400 Surface to Air Missile which was made public later.

Likewise, Chinese President Xi Jinping chose to visit Russian President Vladimir Putin only days after the latter’s implication by ICC in the war crime and both leaders signed into a number of deals which were sparsely reported and not made fully public. Clear anti-US positions of both powers are leading them to co-operate on multiple fronts ranging from advanced military technology to natural resources.

Ukrainian war and Benefits of multi-alignment

The policy of multi-alignment allows India to tread a cautious path and refrain from mounting criticisms against Russia for its aggressive behaviour. By doing this, India believes Russia would not drift towards its traditional adversaries – China and Pakistan posing a direct threat to Indian interests.

Second, India is aware of the fact that any public criticism of Russia for its invasion of Ukraine would completely alienate it from New Delhi as it is a direct party to the war. Third, the policy would prevent India from estranging relationship with a great power which has been a trusted partner based on the crucial and consistent support it has lent to the former historically such as its use of veto at the UNSC on the issue of Jammu and Kashmir and military and security assistance during heydays of the Cold War.

India still needs continuous supplies of Russian made military equipment and technology to run the Soviet era arms and ammunition apart from increasing dependence on its natural resources. Fourth, New Delhi believes India’s strategic partnership with the US would not be hampered as Biden administration understands the Indian predicaments.

Nevertheless, India’s avowed policy of multi-alignment is a peacetime strategy that has been crafted adeptly to secure national interest for it without hampering strategic ties with any power which is not a direct party to a war or is not a direct threat to it.

Everything may go well so far as India desires to maintain a balance in its relationship with the US and Russia. However, during wartimes perceptions even can play a big role. The gap between India’s ambitions and projections as an emerging power and its actual role during such situations can be instrumental in generating perceptions that may impede its interests.

War Situations and Multi-alignment

The evolving war scenario in Ukraine demanded far more clear and categorical response from New Delhi. Despite robust strategic bilateral relations with Russia, India could not leverage the Ukrainian war theatre on par with China nor could it put brakes on Moscow’s ever-increasing drift towards China. Its policy of multi-alignment also cannot take its relationship with the US to the level that the latter maintains with its traditional allies. Its policy of keeping distance from publicly criticizing Russian position only casts it as an ambivalent power in the eyes of the US and its allies in Europe and other parts of the world.

During war situations, the policy of multi-alignment does not pay off as much as proactive stance or secret maneuvering as China is doing in a shrewd way or the allies of the US are doing. India’s apparent neutrality cannot stop China from assuming a far more emboldened role with Russian partnership in the Indo-Pacific region and around the Himalayan landscape.

While India is assured of the US and its allies’ policy of containing China in the Indo-Pacific by supporting the QUAD members in meeting some of their objectives, India’s national interest in the Himalayan landscape will be particularly vulnerable in future. India’s options to fulfill its national interest through its proclaimed policy of multi-alignment are severely constrained in the context of war involving great powers. It can neither alienate Russia by publicly criticizing it for its invasion nor can it dispel the perceptions that its ambivalence stance might have engendered.

Although situations have changed since India refrained from criticizing Soviet Union for its military intervention in Afghanistan in 1979 in the heydays of the Cold War when New Delhi looked upon Moscow as its only strategic partner, the Russian invasion of Ukraine in the post-Cold War era and post-Soviet period has placed India in no better position to take clear position on the issue except making calls for respecting principles of Sovereignty and Territorial Integrity indirectly referring to the Russian action and pressing for diplomatic resolution of the war.

The Afghan and Ukrainian situations are qualitatively different for India in so far as while in the case of the former, India’s diplomatic stance was clearly based on its national interest; in case of the latter it is just a response to an awkward situation. India has forged close strategic ties with the US unlike the Cold War days and both had signed many significant defence deals by the time Russia raged war in Ukraine. In the Post-Soviet era, India has also diversified its military and strategic relationships with many countries. Still, India’s response to another war situation remains the same but this time national interests seem to be in stake.

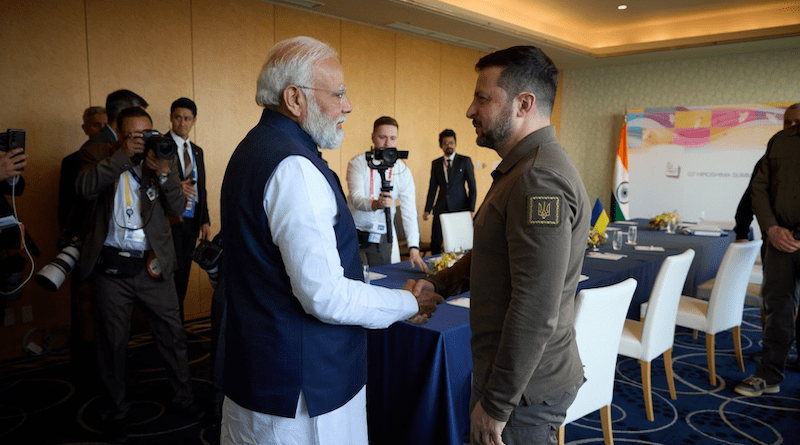

It is a good news that Prime Minister Modi met with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy for the first time since the war erupted on the Ukrainian soil in February, 2022 on the sidelines of G-7 Summit in Hiroshima, Japan very recently and described the ongoing war on the Ukrainian soil as a humanitarian issue and committed to do whatever possible towards resolution of the war.

The best thing India can do in this context is that it can assume a more proactive role to find diplomatic solutions to war by using the platform of the dormant Non-Alignment Movement (NAM) and by counting on the support of the Global South. India need not blame any country for the war still efforts can be undertaken proactively to signal that it is not merely country with great power ambitions but it can fulfill obligations arising out of it. Rejuvenating and reenergizing NAM can be an apt response to the war situations including the war on the Ukrainian soil.

Dr. Manoj Kumar Mishra, Lecturer in Political Science, SVM Autonomous College, Jagatsinghpur, Odisha, India