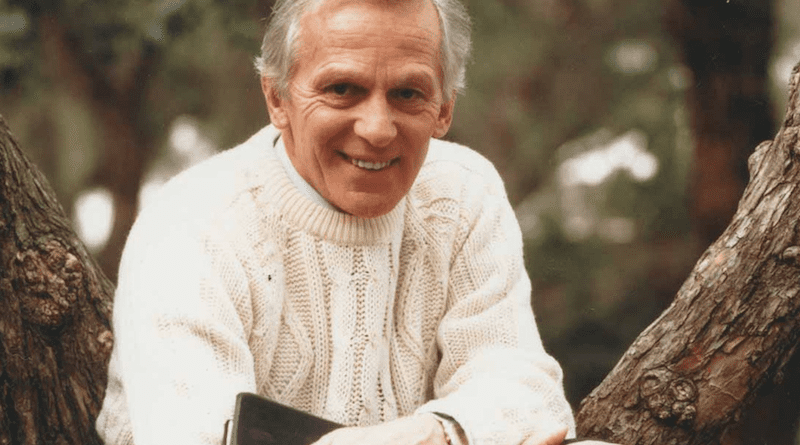

Brother Andrew: God’s Smuggler – OpEd

By Doug Bandow

Modern Christians typically visualize martyrs as historical figures, such as believers killed for entertainment in ancient Rome’s Coliseum. However, Christians of all varieties continue to die for their faith to this very day. Many more face imprisonment and torture, subject to the brutal whims of others.

Most martyrs live heroically but anonymously, unknown to anyone outside their own family or community. Some are raised up in ministry and serve a wider population. A few become symbols of the persecuted church. The sort of faith that animates such people, wrote the Apostle Peter, is “of greater worth than gold, which perishes even though refined by fire” (1 Pet. 1:7).

A Dutch missionary named Anne van der Bijl, better known as Brother Andrew, was an evangelistic giant for the persecuted. He died in September of 2022, at age 94, but his life’s work continues. Where others saw walls, prisons, guards, and resistance, Brother Andrew saw opportunity: “Our very mission is called ‘Open Doors’ because we believe that all doors are open, anytime and anywhere.” He added that “I literally believe that every door is open to go in and proclaim Christ, as long as you are willing to go and are not worried about coming back.”

Of course, most people want to come back. Indeed, Brother Andrew seemed frustrated that so many believers seek safety and prosperity. Brother Andrew “was equally opinionated about the Western church; our camp drew his sharp criticism. It was difficult for a man who would risk meeting with Pakistani extremists to understand how those completely free to be part of a church or read their Bibles would not do so,” wrote David Curry, president of Open Doors USA, the organization founded by Brother Andrew to smuggle Bibles into communist Europe.

People being people shouldn’t surprise us. But that truism makes Brother Andrew’s life even more extraordinary. He saw the plight of the persecuted as a responsibility of all Christians. He emphasized that everyone was capable of helping those in need and sharply dismissed those who emphasized the risks he took: “Every place is dangerous,” including “every place outside the will of God.” Brother Andrew urged Christians to follow those before them in being willing to sacrifice everything: “This is what I saw the Russian and the Chinese Christians do under communism: lay down their lives in the gulag, the re-education camps, the labor camps. That’s why the Church won.”

Nevertheless, God doesn’t expect everyone to confront authoritarian states and foreign despots. Indeed, the majority of Open Doors’ current employees live and work far from the sort of perils that characterized Brother Andrew’s early ministry. He contended that he was “not an evangelical stuntman,” but rather “an ordinary guy.” He challenged the rest of us: “What I did, anyone can do.” Nevertheless, near the end of his life he still wished he had done more. When queried if he had any regrets after decades of service, he responded that he “would be a lot more radical” if given another chance.

Brother Andrew’s life illustrated the Apostle Paul’s famous quandary. So much more good work for him to do in this world, but so much new promise awaiting him in the next one. In an official statement from Open Doors upon Brother Andrew’s death, his colleagues observed: “For more than 60 years, Open Doors’ founder—Brother Andrew—visited over 125 countries in service to the global church. It’s with mixed feelings that we share his greatest journey yet.” They concluded that “God used Andrew’s obedience and prayers to change millions of lives and eternities. We are grieving but we are equally thankful. Celebrate our brother’s homecoming with us today.” After all, on his last voyage as he passed from this world to the next, God was sure to welcome him with the injunction, “Come and share your master’s happiness” (Matt. 25:23).

Resistance Began Early

Brother Andrew led an eventful life from childhood. Born in 1928, the son of a blacksmith and semi-invalided homemaker, he was a teenager during Nazi Germany’s occupation of the Netherlands, his homeland. Food was scarce, forcing him and his five siblings to subsist as best they could, including on tulip bulbs.

He engaged in resistance activities, though their impact was marginal. As The Economist noted: “In the middle of the night the boy would creep down from the loft, steal his mother’s precious rationed sugar and pour it into the German soldier’s petrol tank.” More seriously, he was forced to hide to avoid German labor conscription, showing him the reality of political totalitarianism.

After the Netherlands’ liberation, he joined the military, helping to reclaim the Dutch East Indies, present-day Indonesia, which had been seized by Japan. The resulting dirty war affected him deeply, wrote Christianity Today: “He was haunted, after, by the sight of a young mother and nursing boy killed by the same bullet. He started wearing a crazy straw hat into the jungle, hoping it would get him killed. Van der Bijl adopted the motto, ‘Get smart—lose your mind.’”

His spiritual conversion began while being cared for by Christian nurses—one of whom he later married after they met again back in the Netherlands—while recovering from a gunshot wound. Through this process, he developed a strong love of the Bible, explained Curry:

Andrew really believed what all Christians are supposed to: that the Bible changes people. It was his passionate love of Scripture that had transformed him from an injured war veteran to a champion of the global church. Andrew believed, unquestionably, that if he could get anyone—an extremist, a lazy American worshipper, a nonprofit CEO like myself—to keep reading the Bible and wrestling with Scripture, that our heads would clear and our hearts would chase what’s right. Whatever wisdom and courage we needed would stir in us over time.

Brother Andrew’s conversion was completed after attending a revival meeting back in the Netherlands. At the time, he was working in a factory, but his newfound faith gave him a new life, in which he felt called to share the Bible: “I promised God that as often as I could lay my hands on a Bible, I would bring it to these children of his behind the wall that men built,” and he would do so “to every … country where God opened the door long enough for me to slip through.”

In 1953 he moved to Glasgow, Scotland, to enter the Worldwide Evangelization Crusade Training College. His studies ranged from systematic theology to auto mechanics. Eager to engage the world around him, Brother Andrew soon visited West Berlin.

The city was an oasis for people seeking to escape to the West. Indeed, it was the flight of so many younger and professional East Germans that caused the communist regime to later wall its people in. There Brother Andrew encountered the recent conflict’s aftermath. According to The Times, Brother Andrew remembered “the flotsam and jetsam of the Second World War—the stateless, the homeless, the confused and the forgotten—lived in squalor alongside more recent refugees, those who had made a narrow escape as the Iron Curtain descended across Europe.”

In the Soviet Empire, religious liberty shrank dramatically. Although persecution could be violent, hostile communist governments employed more subtle punishments as well: As reported by The Economist:

Religion, [Brother Andrew] learned, wasn’t banned under communism; it had been co-opted by the state. In Czechoslovakia ministers had to renew their licenses every two months, and submit their sermons in advance for official approval. Where they could not beat God, the authorities tried to outshine His appeal. In East Germany they offered free “Welcoming Services” instead of baptism. Or wedding services that were legal and free of charge. Those who saw God as the higher authority were told they were misguided. Many lost their jobs and were imprisoned.

Brother Andrew’s ministry effectively began on a trip to the 1955 World Youth Congress in Poland, which had been swallowed by the Soviet Union. The gathering was meant to showcase communism, but he carried religious tracts with him, distributing them to Polish citizens and Soviet soldiers alike. He also spoke to members of an underground Christian church.

He had prayed for God’s guidance and found his mission. The following year he drove to Moscow, where he distributed Bibles and other religious literature. At the start it was him, a few friends, a small car, and faith. Indeed, he found it difficult to say no. When asked to take more Bibles along, recorded The Economist, he “wasn’t so sure. Their car was already weighed down. Then some other friends came with a whole carton of Ukrainian Bibles. ‘Of course we’ll take them,’ his fellow smuggler said, stowing them openly on his lap. ‘If we’re going to be arrested for carrying in Bibles, we might as well be arrested for carrying in a lot of them.’”

He recruited other Christians to help. After all, “we know there is no one-man show in God’s family. The great task couldn’t be accomplished by Brother Andrew alone,” wrote Eternity News upon his death. “There must be many, many Brother Andrews—big ones, small ones—who unitedly take up the burden. Here we give our thanks to all the ‘big’ Andrews and ‘small’ Andrews.” Like a well-trained military, they experimented, varying tactics, locations, vehicles, and companions. One couple posed as honeymooners.

Opening Border Doors

Looking back nearly seven decades, his efforts seem almost glamorous, like being a spy for God. However, smuggling was and remains a dangerous business, requiring that border guards, tasked with “protecting” their people from outside information, not see (or do anything if they do see) religious contraband. Brother Andrew offered a simple prayer: “Lord, when you were on earth, you made blind eyes see. Now, I pray, make seeing eyes blind.”

His experience affirmed his godly call. According to a news report, on one trip he watched border guards search the cars before him for contraband. “‘Dear Lord,’ Brother Andrew recalled praying, ‘What am I going to do?’ As he prayed, a bold thought came to Brother Andrew: I know that no amount of cleverness on my part can get me through this border search. Dare I ask for a miracle? Let me take some of the Bibles out and leave them in the open where they will be seen. Putting the Bibles out in the open would truly be depending on God, rather than his own intelligence.” He was waved through the crossing.

Brother Andrew’s battered blue Volkswagen Beetle, a gift from a neighbor, became a symbol of his mission. The Cold War raged, putting his life and, perhaps more important, mission at risk. On his first half dozen trips, he passed through borders unrecognized, his spiritual wares unnoticed. But he was arrested in Yugoslavia, though he was deported rather than imprisoned. After that he founded Open Doors to bring order to his mission.

Even then, his efforts remained modest and little known. But in 1967 he published his autobiography, God’s Smuggler. In an age before instant celebrity and social media, Brother Andrew sold 10 million copies in 35 languages. His unexpected notoriety transformed Open Doors, greatly expanding its funding and reach. He wrote another 16 books, but God’s Smuggler gave him another name, both vivid and descriptive. After the book’s publication and his public recognition, he left smuggling to others.

His work was controversial, and groups including the American Bible Society, Baptist World Alliance, and Southern Baptist Foreign Mission Board worried about the danger to those he helped. Yet his efforts are believed to have delivered more than a million Bibles to the “Evil Empire,” as President Ronald Reagan labeled the Soviet Union and its Eastern European satellite governments. A common joke was that if the Soviets had won the celebrated “space race” to the moon, they would have found Brother Andrew there, waiting with Bibles. He was characteristically modest, saying that he did not track the number of Bibles smuggled because only God could be the perfect bookkeeper.

However, there was much more to do. Brother Andrew discovered that his visits filled more than material needs. A Baptist pastor told him: “Even if you had not said a word, just seeing you would have meant so much. We feel at times as if we are all alone in our struggle.” That encouraged Brother Andrew to think more broadly about his mission: “What persecuted Christians want is spiritual communion and companionship. They need to know they aren’t alone in their struggle.”

Even The Economist, a liberal-minded British publication, was taken with his role:

“You know, years ago I knew that people in the West were praying for us,” a Romanian Christian once told him. “But now for many years we have not heard from them. We’ve never been able to write letters, and it’s 13 years since we received one. It has come to us that we are forgotten, that nobody is thinking of us, nobody knows our need, nobody prays.” As soon as he got home, he promised, he would tell so many people about the little Christian community in Romania (or Bulgaria, or Poland, or Russia—wherever he happened to be) that never again would they feel alone.

The more he worked the more he sought to do. Open Doors explained: “As our ministry expanded, other needs emerged. For example, in some countries pastors have little or no seminary training. We provide them with training so they can be more effective leaders of their congregations. In other regions Christians are discriminated against, denied education and quality job opportunities. So we may strengthen the church by providing small loans to help Christians start businesses. The needs and thus the strategies vary from country to country.”

Today Open Doors is an international behemoth focused on the persecuted. The organization has 25 national offices and operates in 70 nations. It has greatly expanded the scope of Brother Andrew’s original ministry. In 2021 Open Doors trained 3.4 million persecution victims in everything from leadership to trauma care, distributed 1.3 million Bibles and other religious materials (many written in minority languages), and provided nearly 700,000 people with emergency relief from both violence and natural disasters.

The organization also advocates on behalf of the persecuted. Of particular note is its research on persecution worldwide and publication of the annual World Watch list, which ranks the 50 worst persecutors of Christians. In the main, there are few surprises: persecution is concentrated in an almost continuous belt from North Africa through the Middle East and Central Asia ending in the Pacific. The 2023 listranks North Korea first, followed by Somalia, Yemen, Eritrea, and Libya. Other notables are Nigeria at 6, Pakistan at 7, Iran at 8, Afghanistan at 9, India at 11, Saudi Arabia at 13, China at 16, Cuba at 27, Mexico at 38, and Nicaragua at 50. The organization also produces detailed “dossiers” on the worst abusers.

Private advocacy for the persecuted has become more important as those who make and implement foreign policy increasingly treat religion as an embarrassment, an afront to their sensibilities and popular conceptions of modernity and morality. A commitment to human rights should naturally include support for religious liberty. Indeed, assaults on this most fundamental form of freedom of conscience represent the famed canary in a coal mine, warning of a flawed political order and inevitable violations of other fundamental rights.

A One-Man (Peaceful) Crusade

Brother Andrew quickly learned that persecution comes in many forms. Some are brutal and simple—such as the murderous depredations of the Islamic State. Others are less violent but more sophisticated. As reported by St. James’ by the Park, Brother Andrew saw

the subtle ways in which the communist authorities, instead of banning the Church, ground down its leaders and worshippers, ensuring that they were demoralized. Christian agitators lost their jobs for spurious reasons and were denied university places without explanation. State-sponsored official churches gave the impression of a freedom of faith while underground churches, where allegiance to the state did not go hand in hand with allegiance to faith, were persecuted.

The Soviet bloc remained Brother Andrew’s focus throughout the Cold War. His Dutch passport gave him access to nations typically closed to Americans. He remained indefatigable, in 1968 visiting Czechoslovakia, in which the so-called Prague Spring had been crushed by the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact. He boldly handed Bibles to invading Soviet troops.

Perhaps the greatest honor bestowed upon him inadvertently came from the KGB, the ruthless defender of the Soviet state and all it stood for. As The Times reported, after the USSR’s demise, Brother Andrew “obtained copies of the KGB reports numbering more than 150 pages about his work in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. He was surprised that they had known so much about him, but had been unable to stop his work.” The itinerant Dutchman had humbled the Evil Empire.

However, Brother Andrew did not limit himself to Europe. In 1965 he visited Maoist China. Per The Times obituary: “He found a more dispiriting atmosphere than anything he had seen in Eastern Europe—indifference and apathy. Instead of a persecuted Church, he found Bibles on sale but no one buying them, and seminaries with evidence that western missionaries had collaborated in espionage with their own embassies. He left the vast country, where countless western missionaries had proselytized less than a century earlier, a broken and disillusioned man.” He later returned to a more open China and achieved greater success. Indeed, in 1981 a 20-man Open Doors team sailed along China’s coast and floated a million Bibles and other materials into China. Unfortunately, the communist giant is returning to past levels of persecution.

He found Cuba much less restrictive, however; it helped for him to emphasize his Dutch citizenship, given the widespread view of America as the enemy. He also traveled to Uganda, then ruled by the mercurial but brutal Idi Amin, who put Brother Andrew on a death list.

The Middle East became a major concern once the Cold War ended. He first visited that region with a trip to Lebanon during its horrific civil war. Again, his geopolitical independence aided his efforts: “With Bibles in hand, he went to see the prime minister and the president, and most of the generals of the various armies engaged in the civil war,” reported The Times. “He also had his first contact with Ayatollah Fadlallah, the spiritual inspiration for the fundamentalist group Hezbollah. Later, he made contact with Hamas, when their leaders were deported by Israel to southern Lebanon.”

These activities might give some evangelicals pause, but he believed peacemaking to be another calling. Per Eternity News: “He took private meetings with leaders of several Islamic groups. He was one of the few Western public figures to regularly go to those groups as an ambassador for Christ.” Indeed, in his 90s, Brother Andrew visited Pakistan to meet the leader of the Taliban to deliver his message from God.

He evidently preferred religious missions to military invasions. He sharply challenged Americans with his call to pray for Osama bin Laden. “I believe everyone is reachable. People are never the enemy—only the devil,” he was quoted as saying in Christianity Today. “Bin Laden was on my prayer list. I wanted to meet him. I wanted to tell him who is the real boss in the world.” For the same reason, Brother Andrew expressed disappointment in the killing of Bin Laden.

He pressed Christians to respond to Islamist terrorism by engaging Muslims. He contended that “we are fearful because we stay home and prepare for the worst to come, because we think that’s what they are planning. That may be true, but it’s because of our inactivity. The moment we take the offensive and plan to go there, we lose our fear.” Brother Andrew emphasized love even in dealing with terrorists. “When we have an enemy image of any political or religious group or nation,” he insisted, “the love of God cannot reach us to call us to do something about it.” He frequently turned the word Islam into an acronym for I Sincerely Love All Muslims.

He further emphasized the importance of Western Christians aiding their Middle Eastern brethren. Again, from Christianity Today:

The Christians there can do nothing unless we start doing something. They depend on us. We are one body in Christ. We are not reaching out to the Arab Christians or to the Palestinians, nor barely to the Messianic Jews, and we are certainly not reaching out to the other Jews with the gospel because they are already God’s people, and they have no choice and we don’t give them a choice. [Middle East Christians] have few resources in their own country, and we in the West have all the liturgy and all the wealth and all the insight and knowledge. This is our eternal shame. We ought to do something.

What Shall We Do Now?

Given the experience of the past two decades, Brother Andrew’s views may seem naive, failing to recognize the depth of evil in this world he was trying to convert. Even some of his supporters doubted the effectiveness of his high-profile personal contacts. However, the outcome of U.S. government policies show the desperate need for a new approach, and Brother Andrew’s willingness to reach out in a winsome way won support. Observed Jack Sara, Bethlehem Bible College president: “He had a soft heart for those in pain, the persecuted, and those usually considered on the other side, the enemy. He was willing to step into a difficult place and talk with difficult people, but never compromise the message of the gospel.”

Brother Andrew also perceived God’s providence and purpose in persecution: “I don’t pray that God will lift the persecution,” he told theChristian Post in 2013, “because if there is persecution there is a plan that God has, otherwise God wouldn’t allow it.” He elaborated: “How do we pray? Not for God to remove persecution, but use that to purify the Church. And it is my strong belief that the countries where there is persecution are stronger in faith than churches in countries where there is no persecution.”

While he was brave by choice, those he ministered to and served were brave by necessity: “He never ceased to be amazed by those he met,” wrote The Economist. “The people in Macedonia who were too scared to come to church unless it was dark, but come they did. The people in Bulgaria who would arrive at intervals so that at no time did it appear as if a group was gathering. It took an hour for 12 of them to assemble.”

Now he is gone and the rest of us must step up. As David Curry observed: “And now, we press on. Because in the words of Brother Andrew, ‘there is more work to do.’” Indeed, this is Jesus’ message to us today. The Great Commission continues to call: “Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit” (Matt. 28:19).

Jesus sent Brother Andrew to the communist and Muslim worlds. Jesus sends the rest of us to our neighbors, co-workers, friends, customers, and more. Brother Andrew was an exceptional “ordinary guy.” So are the rest of us in our own ways. That may be the most important message to take from his exceptional life. Brother Andrew should inspire people today no less than in the past. We are to be like him, but not necessarily in action. Rather, we should model him in spirit, to be a “good and faithful servant” and to trust and follow God.

About the author: Doug Bandow is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute. A former special assistant to President Ronald Reagan, he is author of Beyond Good Intentions: A Biblical View of Politics.

Source: This article was published by the Acton Institute