The US-UK Special Relationship: Time For A Reset, Not An End – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Charles A. Ray

(FPRI) — The US-UK special relationship, one of the longest and closest bilateral relationships of the twentieth century, is often questioned by those who fail to see the benefits that it provides to both sides. The United States benefits from being able to work through British counterparts in many parts of the world where the United Kingdom enjoys longer historical ties, and has access to the UK intelligence networks in countries where there is no US presence like Iran and North Korea. The United Kingdom has closer relations and easier access to the US defense industry than anyone, except perhaps the Germans, access to US technical intelligence through bilateral intelligence sharing agreements, and can depend on the US security guarantee. UK diplomats in the United States have higher level and easier access to senior policymakers and legislators than any other country.

There is no doubt that the relationship needs a reset to take into account the difference in the two governing systems, and to ensure a more equitable relationship, with both countries working to their strengths and recognizing that, like siblings who have been raised apart from each other, they will sometimes disagree, but must learn to do so without being disagreeable.

The Special Relationship: A Long History

In 1946, former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill coined the term “special relationship” to describe the close political, cultural, and historical ties between the United Kingdom and the United States. Since World War II, Britain and the United States have had extremely close ties in several areas, but the so-called special relationship hasn’t always been all that close.

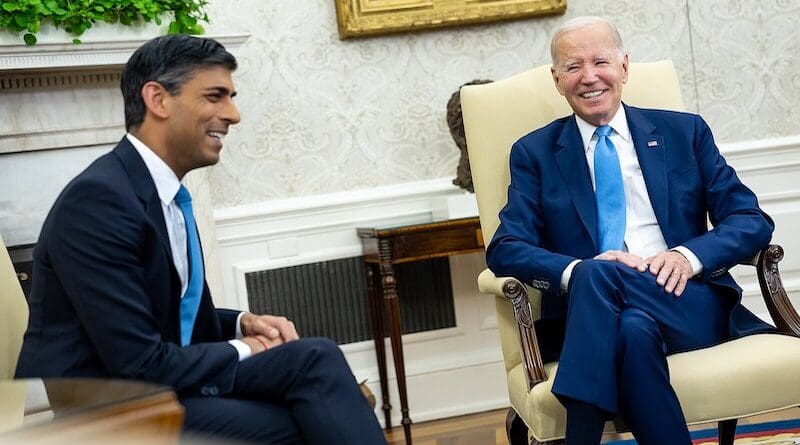

Oftentimes, the closeness of the relationship has depended more on the personal chemistry of the two countries’ leaders than the long-shared history and culture.

Churchill and Harry S. Truman, for example, having just defeated Nazi Germany and sharing a mutual distrust of their ally, the Soviet Union, had a very close relationship. In the 1980s, Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan had a particularly close relationship, so much so that Thatcher called Reagan “the second most important man in my life” after her husband. In the 1990s and early 2000s, especially after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Tony Blair and George W. Bush had a close bond. During the administration of Barack Obama, on the other hand, Obama and David Cameron got along personally, but butted heads on several international issues. Despite public displays of comity, Theresa May and Donald Trump had a problematic relationship, with her writing in an article that “with Donald Trump, I never know what to expect.” Trump had a good relationship with Boris Johnson, ostensibly because Johnson was so much like him. However, Johnson was quick to distance himself from the former president when President Joe Biden defeated him in 2020. It is too early to tell what the relationship is or will be like between the two current leaders.

But, the special nature of the US-UK relationship actually predates World War II. After the war for American independence and the War of 1812, which involved the two countries (or in the 1770s, Britain and its soon-to-be former thirteen colonies), Britain’s fear that its trade with North and South America would be jeopardized if other European powers weren’t blocked from further colonization of the so-called New World, and America’s concern of Spain and Russia’s territorial ambitions in the hemisphere, drove the two countries together. British Foreign Minister George Canning suggested a joint British-American declaration banning future colonization of Latin America. President James Monroe was favorable, but Secretary of State John Quincy Adams argues that it should be an exclusive American policy, which resulted in the Monroe Doctrineof 1823. This act, which the nascent American navy could neither sustain nor enforce, and needed the British fleet to deter potential aggressors, is the first example of both the positive and negative aspects of the US-UK relationship. While even in the early days of the republic there was an American tendency to “go it alone,” there was also a recognition of the symbiotic relationship between the two, both from a mutualistic and parasitic point of view. Both countries value the mutual benefits of the relationship, but at the same time, at the end of the day, put their individual interests first. We’ve seen this in the current age, with the US administration’s position against Brexit, and the British negative reaction to the US decision to withdraw from Afghanistan without consultations with the UK leadership.

What Does Each Country Get From the Special Relationship?

That, then, brings up a salient question. Has the “special relationship” outlived its usefulness? Should it be junked and the United States and United Kingdom kiss and part friends?

The answer to these questions can’t be a simple “yes” or “no.” Looking at the history of the relationship it seems clear that it needs to be reevaluated, and adjusted to the mutual benefit of both parties. But reset doesn’t have to imply a repudiation of the relationship. In fact, in the turbulent current age, this is the last thing either country should be contemplating.

Both countries benefit greatly from the special relationship, despite the occasional hiccups. The United States benefits from UK presence and human intelligence collection in areas where there is no American presence, and from the UK running point in countries that are part of the British Commonwealth, or former colonies where the United States has less well-established relationships. UK diplomats in Washington enjoy more access to senior policy makers and legislators than other countries because of the special relationship, have more access to the US defense industry, and, thanks to US-UK intelligence sharing agreements, have access to US technical intelligence.

Winston Churchill once described the United States and United Kingdom as two nations divided by a common language, and while that’s somewhat tongue in cheek, there’s also more than a grain of truth there. While the United States descended primarily from the English colonists that came to the “New” World, over the intervening centuries, America and Britain’s respective experiences as nations has created two unique entities. This is not to say that the countries no longer share a common heritage, just that, like siblings separated at birth and raised in different environments, we’re not clones of each other. This does not mean that those siblings cannot establish a close relationship, a “special relationship” even. It simply means that the countries must never lose sight of their uniqueness.

In terms of the US-UK special relationship, there is a need for both parties to look at it realistically. The United States should not expect the United Kingdom to blindly follow or agree with every US position, and the United Kingdom should recognize that there will be times when it should say no and follow its own course, even when that course counters the United States. Even the best of friends will disagree on occasion, but true friends disagree without being disagreeable. The relationship should be put on a more equitable footing, recognizing that each party will pursue its own interests first, but each will also seek ways to support the other.

The Special Relationship On the Ground

They’ve done it in the past, and they can do it again. In 1993 to 1996, for example, during the rebel war in Sierra Leone—after the government had been taken over by the nation’s military in a coup d’etat—democracy activists pushed for elections. Many in the West, including some senior US officials, didn’t believe that elections were possible. The US charge d’affaires, working with the UK ambassador in Freetown, was able to pull together an international coalition of like-minded foreign diplomats and UN representatives to convince the military junta not to oppose elections, and to convince our respective capitals to support the process. It’s no exaggeration to say that the 1996 election of a civilian president in Sierra Leone would never have happened if the United States and United Kingdom hadn’t presented a united front in support of the process.

Another situation where the special relationship between the United States and United Kingdom solved a crisis despite some differences of opinion between the leaders in Washington and London occurred in Zimbabwe in 2011. Both countries supported Morgan Tsvangirai, the main opposition to the late Robert Mugabe’s ruling party. But, as is often the case, US support was intensely personality-oriented to the point that even when the opposition did the same things that the United States criticized the ruling party for doing, it was ignored. When members of the opposition, for example, engaged in violence, Washington’s stance was to basically ignore it, while the UK ambassador in Harare took a more realistic and diplomatically sound view that the opposition the United States supported had to live up to high standards and that bad behavior had to be called out regardless of who it was. The relationship between the US and UK ambassadors was such that the US ambassador, despite not having received instructions from Washington to do so, joined his UK counterpart and delivered a blunt message to Tsvangirai that if he didn’t take action to deal with the violence within his party, assistance would be suspended. There was some resistance to this stance in Washington, but when appropriate actions were taken and the suspension of assistance was lifted, Washington reluctantly agreed that it had been the right course of action.

There are strong feelings in some quarters that the relationship is one-sided and that the United Kingdom sacrifices its own diplomatic strength in order or slavishly follow US dictates. While this might have happened in some instances, it is not the whole story. The US position of imposing sanctions on Mugabe’s government in Zimbabwe after some land seizures, for example, was not an American initiative. While the United States did become an avid proponent of these sanctions, the initial impetus for them came from the United Kingdom.

Is the relationship perfect? No. Is it sometimes one-sided? Yes. But, this could be said of almost any relationship. Both sides need to adjust expectations and set limits on the relationship, and make it clear that while they will sometimes disagree, in the end the relationship will endure because both sides benefit from it in the long run. In addition, when the United States and United Kingdom present a united front to the world others benefit from that relationship.

The Future of UK-US Relations

There are a number of things that both parties could do to reset the relationship.

The United States should keep in mind that military might is not always the best solution to problems, and understand that compromise and accepting the advice of others is a sign of wisdom, not weakness. It also needs to take a longer term view when approaching international crises and issues, accepting that other countries have differing cultural views. Finally, the United States should accept that other sovereign nations have interests that are as important to them as ours are to us, and learn that disagreement is not a judgment but an opinion.

The United Kingdom should understand that the US government structure, with an independent, often hostile legislature, seems inefficient when compared to the parliamentary system, and be more willing to push back when a US policy or action seems inappropriate for the situation. Learn to disagree firmly without being disagreeable.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Foreign Policy Research Institute, a non-partisan organization that seeks to publish well-argued, policy-oriented articles on American foreign policy and national security priorities.

- About the author: Charles A. Ray, a member of the Board of Trustees and Chair of the Africa Program at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, served as US Ambassador to the Kingdom of Cambodia and the Republic of Zimbabwe.

- Source: This article was published by FPRI