Persian Tweeters Make Omid Kokabi Trend Globally

Simultaneous with the ninetieth birthday of Queen Elizabeth II and the sudden death of rock icon, Prince, throughout the afternoon and evening of Thursday April 21, Tehran local time, the hashtag FreeOmid# was trending among the top three or four Twitter posts across the world.

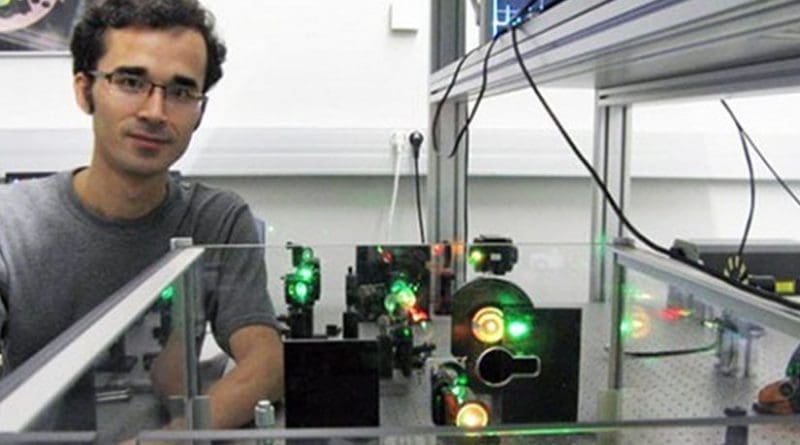

The Free Omid phrase referred to Omid Kokabi, the Iranian scientist who is the most non-political political prisoner in Iran. A doctoral candidate studying physics in the United States, he came to Iran in February 2011 to visit his parents. A day later he was called on by the office of the Atomic Agency, which offered a job that Kokabi then declined. He was arrested in the airport and held in the solitary for 36 days. He was denied due process and, after months in limbo, was finally tried and sentenced to 10 years in prison for “links with hostile governments and illegitimate earnings”.

His family and lawyer maintain that the only reason for his conviction was his refusal to collaborate with the security and military institutions of the Islamic Republic.

In March, it became apparent that Omid Kokabi is afflicted with cancer. The cancer is said to be four years old, and he has spent every day of those four years in jail without one single day of leave. In the five years that he has been in prison, he has suffered from kidney pains, and tests in prison led to a diagnosis of kidney stones. He was not allowed to have tests or treatment outside the prison until April 20, when doctors were forced to remove his right kidney.

The Special Case of Omid Kokabi

Omid Kokabi is a special case on several levels. Although saying no to participation in the non-transparent military-security activities of an undemocratic government is a completely political statement, he has never been directly involved in any form of political activism before or during his arrest. He was not in Iran during the election protests of 2009 and could not be branded with the “assembly and collusion against national security” charge. The letters he has written after his arrest have been more legal statements rather than political: He insists on his innocence, objects to the legal proceedings and insists that the reason for his arrest was his rejection of security-military institutions.

Kokabi insists that scientists should not collaborate on projects that could pose a danger to human beings.

Scientists’ Honour

In a country where the statement “I am not political” is a secret code for acceptance of the regime’s demands and compliance with the existing unfair relations, and one’s “profession” is a valid excuse for any form of collaboration and complicity with the regime, Kokabi has stood up against all threats, been saddled with a 10-year prison sentence, become afflicted with cancer and lost his kidney.

While he has five more years to serve, he says: “Believe it or not, after five years, I still do not understand why I am in this predicament.”

Omid, Twitter History

Kokabi’s transfer to hospital and the removal of his kidney drew reaction from Amnesty international and several human rights groups and activists. Foreign-based, Persian-language media reflected the news like similar reports from Iran. Inside Iran, only ILNA published the news about Kokabi’s cancer, and all other media were silent on the matter.

What occurred on Twitter, according to Iranians tweeters, marks a historic line in Persian Twitter history that separates what came before and what happens going forward.

Prior to this, issues like the nuclear negotiations had trended on Twitter, reaching the top 10 global trends. With regard to Kokabi, this was the first time that users managed to transform the issue into an important Twitter post without media support and without advance preparations.

On April 21, tweets using the FreeOmid# hashtag numbered 220,000 by the end of the day Tehran time, and the trend continued; however, Persian tweeters left as the day wound down, and the hashtag was no longer trending at the top.

It is not exactly clear who is responsible for this Twitter surge, but a number of human rights activists and independent alias Twitter users with large followings played a role in it.

What is clear is that the users were not directed by any institution or group and they acted on their own simultaneously.

The speed with which the hashtag was picked up caught the users off guard. Moments earlier, one of the users had said: I suppose we won’t even be able to make FreeOmid# go viral.

One user wrote that Twitter’s character limit has changed to 131 from 140, in order to reserve nine characters at the beginning for FreeOmid#.

A journalist in Tehran wrote: “Put aside old feuds; make FreeOmid# trend; then go back to the old feuds.”

The sudden surge in Persian tweets drew in many non-political users, with many asking who is Omid Kokabi. Some who did not want to get caught up in any political movement chose silence or left the internet space.

Some wrote that this was the first time everyone, irrespective of their political biases, was calling for the same thing. Users representing the extremes of the political spectrum echoed the same call for Kokabi’s freedom.

The regime’s supporters and Basij members kept silent or resorted to sarcasm.

A cleric wrote: If Daesh had invaded Iran, you would be trying to trend FreeIran# … while still criticizing the security-military institutions… but I cheer them. Many users responded: As long as we have you, there is no need for Daesh.

One regime supporter wrote: If you are so concerned about Iranian scientists, why were you silent when they assassinated Iranian nuclear scientists?

Another user responded: How does the assassination of nuclear scientists by foreign powers compare to the incarceration of a physics student by one’s own government?

Persian Twitter users, who often make fun of ineffective and purposeless virtual movements with terms like “HashtagAcitivism”, did not think that this time would be any different, or that their input would result in the release of Omid Kokabi. They wrote many times that they just wanted to inform the public and put the issue out there and perhaps reach Omid and lift his spirits a bit.

In addition to the call for Kokabi’s release, there are other sometimes sarcastic and sometimes more direct calls for President Rohani’s minister of health, who seems to enjoy making media appearances and paying visits to celebrities, to attend to Kokabi in person.

Journalists urged foreign media to share the news about Omid’s medical situation.

A call on Iranian celebrities to join the trend fell flat, and Iranian actress Mahnaz Afshar was the only one to join the effort, while actor Rambod Javan posted a tweet on the theme of omid (hope), which was seen as an implicit reference to Omid Kokabi.

Many users slammed celebrities and journalists for their silence on this matter.

President Rohani and Foreign Minister Zarif were also criticized for their lack of effective action regarding Kokabi’s situation.

A Good Twitter Day

It is probably not far from the truth to say that the expanded presence on Twitter on April 21 can only be compared to the activities in that space during the 2009 election protests.

One would have to be far too optimistic to believe that this Twitter storm could have any impact on Kokabi’s situation. But it can be said without a doubt that the users truly exploited the potential of the medium, keeping in mind that Twitter is blocked by the government in Iran, which makes accessibility very difficult for users.

A journalist wrote in a tweet: “While on some days, Persian Twitter is cause for serious disappointment, there are days that make you proud, like the one with Free Omid#.”