Kazakhstan: The Burden Of Being Russia’s Neighbor – Analysis

Moscow is once again using the bogey of Kazakh nationalism

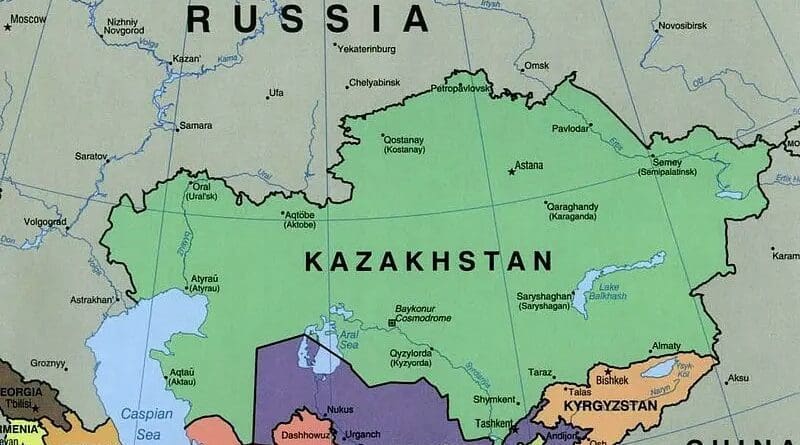

Kazakhstan has recently been facing challenging times. By mid-August 2021, the country found itself in a position that can be described as being caught between two fires, or two kinds of critical situations. Russia carried out a series of informational strikes involving the main propaganda guns, comprising the top Russian TV networks – Channel One, Rossiya 24 and NTV, either state-run or owned by companies with close links to the Kremlin – on the Kazakh governmental policies on nation-building just at a time when all Central Asian governments were becoming increasingly unnerved over the potential regional fallout from the Taliban’s swift and overwhelming victory in Afghanistan following the US withdrawal from the country.

The stronger always blames the weaker

It is yet far from clear which of those two things has upset official Nur-Sultan the most. Here is one more thing that has to be taken into account in assessing the situation under consideration. By mid-August 2021, Kazakhstan became a target for full scale and intensive informational attacks by the Russian media forces for the first time in decades. Nothing like this had ever happened before during almost 30 years of relations between the two nations. Channel One and Rossiya 24, as the major government-controlled national TV channels and the most powerful outlets of the media industry and the main news sources for most Russians, had never before purposefully and systematically criticized the social and political situation in Kazakhstan, and the policy of the Kazakh authorities. But now they have.

Hence the question arises why this had not happened to the Central Asian nation long before that and why it has happened just now, and what the Kremlin’s bigger play is in the context of evolving events.

It all started when Yevgeny Primakov, head of Rossotrudnichestvo, a Russian government agency tasked, in addition to its other duties, with helping ethnic Russians living abroad, reproached the Kazakh authorities for “not denouncing the actions of Kazakh nationalists” through his Telegram account.

Yevgeny Primakov posted this on his Telegram page on August 10. The very next day, the top Russian TV networks started taking the case on with the supposed aim to give as much publicity as possible to the issue he had raised.

At the same time, the largest Russian news agencies and various periodicals began covering that topic under the quite eloquent headings: “Rossotrudnichestvo is concerned about manifestation of Russophobia in Kazakhstan”, “Who did give the go-ahead for the “the Russian question” to be finally resolved”, “How did Kasym Tokayev deal with the “Russian issue”, “Those nationalists in Kazakhstan’s power, who are set against Russia, have been named”, “Defiantly Russophobic moves by the Kazakh authorities immediately after Mishustin’s visit”, “Kazakhstani system of power are being joined by nationalists obsessed with the idea of the “Great Turan”, “Political scientist spoke about the Kazakh authorities’ flirting with nationalists”, “Leader of the “language patrols” is found to have had connections with Kazakhstan’s president”, “Head of Rossotrudnichestvo called for the protection of the Russian-speaking population around the world” and “Kazakh nationalist Akhmetov has been warned of danger from [the Kazakh] ministry of information”. It looks as if Russia has been consistently and purposefully plunged into an atmosphere of information war against Kazakhstan.

The campaign, launched by Yevgeny Primakov as a measure to induce official Nur-Sultan to take steps against the so-called Kazakh nationalists with Russophobic leanings, soon began to be accompanied by a tendency to reproach the very Kazakh authorities for their involvement in the kind of nationalism under consideration and to characterize some of the high-ranking Kazakhstani officials as persons negatively disposed towards Russia and the Russians. It can be assumed that things in this informational campaign were and still are going the way they had been meant to. The stronger, as Russia’s best-known fabulist I.Krylov said, always blames the weaker.

The following is an excerpt from what was said by Sergey Mardan, a journalist and radio host, during his appearance on Channel One’s “Vremya Pokazhet” program of 11 August: “Speaking of which… [the first Kazakh president Nursultan] Nazarbayev [in office from 24 April 1990 until his formal resignation on 20 March 2019] came to power on a wave of the first nationalist pogrom in [19]86, after which he was made first secretary [of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan, i.e. the top leader of the republic at the time]. And that policy of building an ethno-national state has lasted for 30 years nonstop”.

He, as one of three TV show participants on the side of pro-government and patriotic speakers (i.e. on left-hand side of the program’s presenters), said those words in a discussion on the topic, which had been launched by its hosts after reviewing the spots concerning a national of Kyrgyzstan attacking a Russian-speaking girl in a shopping mall in Bishkek, and the actions of Kuat Akhmetov, the organizer of the so-called ‘language patrols’ in Kazakhstan. His team-mate at the side of pro-government and patriotic speakers, Alexander Sherin, first deputy chairman of the State Duma defense committee, who was next in line to be given the floor, called “for the closure of borders [to the Kyrgyz] and the deportation of all citizens of Kyrgyzstan [from the Russian Federation]”. Alexander Sherin also said that Russia must be given credit “for having constructed the Baikonur cosmodrome for them [Kazakhs]”. He’d do just as well to start talking about the great honor given to them through conducting a total of 456 tests (the total impact of which was 45,000 times more powerful than the Hiroshima bomb) at the Semipalatinsk site from 1949 to 1989, and exposing approximately 2.6 million Kazakh citizens to radiation. But if we listen to Llewellyn King, instead of Alexander Sherin, it turns out that the “Soviet view was if it is dirty, dangerous or inhuman, do it in Kazakhstan”. But people like Sergei Mardan and Aleksander Sherin have their own views on the issue concerning Central Asia’s former Soviet republics.

At that gathering, they were given the opportunity to make fairly lengthy statements on what they considered to be essential owing to events in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. In front of them (on the right-hand side) were three men – Yakub Koreyba (a Polish political scientist), Andrei Nikulin (a Russian political scientist) and Vasil Vakarov (a Ukrainian political scientist). It was assumed that they would oppose the aforementioned three persons on Kazakhstan’s and Kyrgyzstan’s topic, too. Yet the foreign nationals looked quite helpless in discussing the issue on August 11. Obviously, these people, despite their many years of participation in Russian political talk shows, did not expect that there might ever be a need to pursue the Kazakh and Kyrgyz topics. Be that as it may, they almost did not enter into a discussion with their opponents in this case. In view of this, Andrei Nikulin had to save the day and take the rap for all three of them. But his speech was over and over interrupted not only by opponents, but also by talk show hosts. He basically managed to say only the following: In taking any (such) action, “one shouldn’t overlook the fact that millions, tens of millions of Russian-speaking people still live there”, and they’ll be “the first ones to suffer from our policy tightening”. Andrei Nikulin was uttering banalities, indeed. Maybe he was not ready for a serious discussion on the topic, since perhaps it had been announced at the last moment before going to air. What else is there to say, if even the talk-show hosts were kind of getting off track a few times and trying to compensate the weakness of the information base with patriotic rhetoric. One of them, Ruslan Ostashko said, referring to his sources in Kazakhstan, the following: “Videos like this, as a rule, are coming from the southern part [of the country]. The central and northern parts of Kazakhstan are quite loyal [to the Russian language and the Russians], while in the south such [Russophobic] sentiments are on the rise”. If, before uttering that, he had paid a little more attention to the personality of the one who triggered this whole media campaign in Russia with videos (showing a small group of Kazakhs, including Akhmetov himself, confronting employees at various businesses and institutions about the absence of Kazakh-language signs and denial of service in Kazakh), he would have known that Kuat Akhmetov was not from the south, but from Kostanay, the center of one of two northernmost (and, the most Russian) regions of Kazakhstan, the second being North Kazakhstan region. On television, in the press, he is said to live in Kostanay and to be a Kostanay-based activist.

So there is reason to assume that Ruslan Ostashko did not have enough time, or did not take the trouble to familiarize himself with at least basic information about the person who had provided a starting point for discussions on his talk-show. Otherwise perhaps he wouldn’t have repeated on the air his sources’ assertions about “the central and northern parts of Kazakhstan” being “quite loyal” [to the Russian language and the Russians] and “such [Russophobic] sentiments” being “on the rise” in the southern part of the country. Even more so now that, according to information in the Kazakh media, “the bulk of the people attending Russian language courses are those from the southern and western regions”.

Ekaterina Strizhenova, the show’s female co-host, did not lag behind him in making contradictory statements, though. Thus, she, summing up the discussion, expressed such a wish: “I want any (ethnic) Russian person, wherever in the world he may be, to know that she or he will be protected”. That sounds a lot like “We in Moscow won’t let anyone do anything bad to ethnic Russians of European origin, living in the Russian Federation and abroad”. Okay. But then the question is, at whose mercy should Russian citizens of [East] Asian origin be left in a situation like this. In modern Russia, these people are quite often being humiliated, degraded and stripped of their innate human dignity, as it was the case with Antonina Li, a third-generation Korean Uzbek, who “moved from Uzbekistan to Russia in the late ’80s in search of better economic opportunities – only to face intense racial persecution for her Korean identity”. It is even worse for those, who are the country’s indigenous inhabitants of [East] Asian descent, since they have no home other than their autonomous republics or districts and they have no place else to go. Russians who run by the slogan ‘Russia for Russians’, target and brutally attack those who don’t have a ‘European face’. As Antonina Li said, after “that, you’re scared, you’re always looking around”, and you receive “no protection from law enforcement officers who seemed to intentionally harass and extort people with Asian facial features”. Isn’t it a terrible thing, to live in a country where you or any other person of your kind is “nobody to that sort of people”?!

Does Russia need an Asian Lives Matter movement?

In light of this reality, the above-quoted statement by Ekaterina Strizhenova, who is eager to defend ethnic Russians with foreign citizenship and, at the same time, completely ignores the deplorable fate of her fellow citizens encountering both racial hatred and racial persecution just for their [East] Asian identity, sounds a lot like a variation of the slogan “Russia for [white] Russians”, which was being shouted by those young ethnic Russians after they had stabbed to death Ainur Bulekbayeva, in St. Petersburg. The Kazakh girl was killed in a hate crime. According to her girlfriend, the assassins, passing by the two of them on the street in the opposite direction, heard Ainur speak on her mobile phone in Kazakh and, turning around a bit later, attacked them with knives from behind, while uttering slurs against the victims. It was an attack aimed at killing, undertaken without any provocation, if not counting the Kazakh speech as such. Is the loss of a human life in this case comparable to the suffering of those ethnically Russian women, who are considered being terribly offended and hurt by an activist campaign to review the use of the very Kazakh language at their worksites in Kazakhstan?! The answer would seem to be quite obvious. Yet the Russian political, intellectual and media elites, apparently, have got a completely different opinion on this matter. It seems to be very difficult, if not impossible, to name yet another country, perceived as part of European civilization, where there would have been as many racially motivated murders of people of [East] Asian descent, as there were in Russia in the 21st century. Among such innocent victims there were quite a few Kazakhs. The following are excerpts from reports of how some of them were killed by extremist Russians: 1. “On a Volgograd city street, 17-year-old skinhead Artem Syrakuzov attacked a passer-by, whose appearance seemed to the skinhead to be non-Russian [non-Europen]. [He]stabbed a man with a knife. The killed person turned out to be Omar Abdurakhmanov, a pensioner of Kazakh ethnicity”; 2.; “In Volzhsk, 15 teenagers beat two Kazakhs, one of them died”; 3. “The assertion of the authorities and law enforcement agencies that there are no skinheads in the city [of Saratov], to put it mildly, does not correspond to reality. Evidence of this is the recent killing of 23-year-old Kazakh Rasim Molzhanov. The only “fault” of the young man was that he was not of Slavic ethnicity [i.e. of European origin]”.

And there are also enough reports that say “they beat him (them) only because he (they) is (were) of Kazakh ethnicity”. Statements about any of the [East] Asian looking people “having been beaten or murdered by extremist Russians because of belonging to a certain ethnicity or an ethnic minority or because of not being of Slavic ethnicity” are euphemistic tricks used by the Russian authorities, law enforcement agencies and media to mask egregious cases of crimes with purely racist motives. For how indeed is it possible to distinguish, among passers-by, a Tatar (Belarusian, Moldavian, etc.) from a Slav or, say, a Kazakh from a Kyrgyz (Altaian, Buryat, etc.)?! The main criterion through which Russian extremists choose their victim in such cases is the distinct racial difference between a person with [East] Asian face features and people of Europeoid or Caucasoid type.

Is racial hatred a mitigating factor at court sentencing in Russia?

Yet this obviousness is being denied or questioned in the country. Regarding the issue of hate crimes, the Russian law enforcement practice proceeds what is completely incompatible with contemporary realities in Russia. Since according to its principles, there have never been and cannot be be racial offenses in the country, and there is no need to introduce a rigorous and effective prosecution of racially motivated crimes against national and ethnic minorities of non-European origin. When Sergey Nikolaev, a Russian IM (International master, in chess) of Yakut ethnicity, had been brutally murdered in Moscow, his murderers from ‘a gang of racist youths’, who committed this crime were ‘charged with murder motivated by ethnic discord’.

After an intense police investigation and much public and media interest, the trial took place. Here is how it was assessed by Boruch Gorin, head the public relations department of the Federation of Jewish Communities of Russia: “If such a [serious] crime, with so many aggravating circumstances, entails such a light penalty, then an outside observer may deem that murder on the basis of national and racial hatred can serve as a mitigating factor at court sentencing [in Russia]. Both society and the criminals themselves perceive it this way”.

“Everything would have been different if the court punished [the perpetrators] to the fullest extent of the law. If it were, the defendants would hardly have dared to [gleefully] shout ‘Sieg Heil’ after pronouncement of the sentence”, – Borukh Gorin said.

Here’s what yet needs to be said. Even the most reputable Moscow newspapers, like Kommersant, in those days reported that this gang of skinheads had targeted specific victims on the basis of ethnicity. Whereas outside of Russia, the actions of these young people were described as just being racist. They had also brutally beat 4 Central Asians and 3 Chinese and killed Altynbek Ashirov, a Kyrgyz migrant. There clearly was a pattern of targeting on the basis of race. But neither the law enforcement agencies, nor the judicial system, nor the media in Russia publicly recognized these criminals as racists. What is there to be surprised, if the next day after the arrest of the murderers of Sergey Nikolaev, the Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs said: “The reason for what happened was ordinary hooliganism. We are not talking about any nationalist motive here ”?! Ivan Koscheev, who was a member of this gang, later said: “It was quite easy to catch us, but the police was ignoring such cases for a long time. In fact, we were just teenage punks. And the police did not care for the migrants who had been injured or killed”. Just one clarification is needed here. This gang had been in the most cruel way mutilating or murdering mainly those who were people with [East] Asian facial features. And it did not matter to them, whether the latter ones came from near or far abroad, or were Russia’s native citizens. In other words, that gang of Russian youths were engaged in a kind of racial cleansing in line with Nazi racist politics. All this seemingly did not bother (to say the least) anyone in Moscow until the relevant events took on a scandalous character.

Since those days, racism and xenophobia, in the view of international experts, have been popping up less in Russia thanks to the measures taken by the Russian authorities. They have seemingly come to this conclusion on the basis of official statistics on hate incidents. Yet a favorable picture, that satisfies such observers appears to be due not so much to intensifying the fight against racism, but launching measures aimed at blocking the activities of those disclosing evidence of racially motivated offenses. Here are two examples of such practice.

First. In St. Petersburg, officials from the local prosecutor’s office visited Mariya Tunkara, a biracial Russian blogger, who has suffered racist abuse, to caution her against “spreading extremist materials”. Damelya Aitkhozhina, an HRW representative says, she watched her “videos and saw nothing inflammatory”.

Second. In Ulan-Ude, the local police, headed by an ethnic Russian, Oleg Kudinov, “are conducting a preliminary inquiry on Article 282 of the Criminal Code against Evgenia Baltatarova, a Buryat journalist and blogger. On September 1, Baltatarova was interrogated about her April youtube video titled “Racism in Russia. What is it and how to deal with it ”, in which she had been talking about [ethnic] Russians’ enmity towards [East] Asians from Russia’s autonomous entities”. Baltatarova’s April youtube video was prompted by an incident of racial discrimination a bit earlier experienced by two Buryat girls in Moscow. Those who had subjected them to racial slurs, with one of the local ethnic Russian women resorting to force against one of guests from Buryatia during the conflict, got off lightly. They were given administrative fines, whereas Baltatarova is at risk of being incriminated under the Article 282 of the Russian Criminal Code which provides for punishment upon conviction in the form of imprisonment for two to five years.

It is generally believed that Russia has never had institutional racism. That’s OK. But then how should the above two stories be qualified? They, sure, can’t be described as instances of systemic racism. However, they do not seem to be ‘exceptional cases’.

The situation in Russia relating to ethnically or racially motivated offenses against people with [East] Asian facial features is being further aggravated by two key contributing factors.

First, the vast majority of ordinary ethnic Russians appear to be zealously supporting the idea of Russia being white, being nationalist, and people being very proud of their presumed racial superiority with regard to the ethnic groups of [East] Asian or African descent. One of the skinheads who had killed Sergey Nikolaev, recalled: “As (we) had beaten a non-Slav in the train, an old woman and an old man, who were nearby, got very excited about it and shouted: “Well done!”. Here is another case. We were beating two non-Slavs at the railway station, and two men, having seen that, said: “Well done guys, you’re right to chase those churkas [subhumans]!”. Among the majority of ethnic Russians, expression of contempt or disgust to even the most prominent members of other racial groups is perceived as an act to be proud of. Here it would be enough to simply cite as an example the case of Irina Rodnina, an MP from the Kremlin’s United Russia party and a triple Olympic champion figure-skater, who “posted an image of Barack Obama on Twitter that was photoshopped to include a banana”. The incident “was widely discussed in the Russian press, with many commentators coming” to the defense of the MP. So the people of the Central Asian or Buryat, Karmyk, Yakut origin and the ones of their kind, who face verbal and physical abuses regularly in Russia, should not hope for some kind of public sympathy. It’s a country, where“so many people openly and even proudly declare their racism”. As Guardian once noted, “racism is rife in Russia”.

Second. The model of racial contempt to Kazakhs and Kyrgyz, as well as to the Russian Federation’s ethnic minorities of [East] Asian origin, is often being shaped by leading Russian politicians and Moscow television celebrities in front of millions-strong audience across the national TV networks and multiple digital and social media.

Thus, Vladimir Zhirinovky, leader of the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (that received 13.14% of the vote in the 2021 elections), recalled the idea of calling Kazakhs ‘zveri’ (‘animals’, ‘beasts’), as, according to him, Kazakhstani Russians did in the Soviet period. Evgeny Fyodorov, yet another State Duma deputy and a member of the Central Political Council of ruling United Russia party, called the titular ethnic group of Kazakhstan, the Kazakhs, ‘nitshebrody’ (‘vagrants and beggars’, ‘trash’, ‘homeless people who beg for alms’). In Russia, these verbal offenses, of course, met no objection by anyone whatever. This is hardly surprising since resorting to humiliation of others as a form of national self-affirmation seems to become increasingly popular in the country. Uttering such offensive words against members of Russia’s minority groups of [East] Asian descent is also a common practice among those considerably influencing Russian public and political opinion.

Here is a vivid example of this. In July this year, Anfisa Chekhova, a famous Russian socialite, TV host and model, compared Buryat women with ‘bomzhikhi’ (it means unpleasant looking female vagrants, sunk to the depths of poverty and squalor). It caused a storm of resentment among Buryatia’s titular ethnic group members. Buryat ombudswoman for human rights, Yulia Zhambalova, asked the investigative committee of Russia to check Chekhova’s speech for possible violations of law. But this appeal, as far as we know, did not bring any results. Anfisa Chekhova, just like Boris Korchevnikov, a host on the state-owned television channel Rossiya-1, who earlier described the Kalmyks [Russia’s another ethnic minority of [East] Asian origin] in the same way on his TV talk-show, has continued to live her life peacefully. Their experience, apparently, should be taken as evidence that the Article 282 of the Criminal Code does not apply to Russian TV celebrities. Also in July this year, Dimosthenis Karmiris, a sports commentator in Greece who made an on-air remark about South Korean athletes (those words, deemed racist by ERT television, were “their eyes are narrow so I can’t understand how they can see the ball moving back and forth”) was sacked. “Racist comments have no place on public television”, ERT said in the statement. Things are quite different in Russia.

After 20 March 2021, the top Russian TV networks were making fun of Joe Biden stumbling thrice while boarding Air Force One on his way to visit to Atlanta. As was well known, he went there for the purpose of meeting with Asian-American leaders and condemning the rising violence against the community after six Asian women were shot dead in the US state of Georgia. Yet the reason for that visit were almost totally neglected by the Russian mainstream media. It looked like a kind of conspiracy of silence. RIA Novosti’s Irina Alksnis has been almost the only one author to speak specifically on the topic linked to prejudice toward Asians in America in the Covid-19 Pandemic. Yet everything becomes clear when you look at the title of her article, reprinted by a few Russian periodicals, on the matter: “New white people in the US: Asians are bearing the costs of their success”. That sounds like a highly unethical, even cynical reasoning at a time when there are increases for anti-Asian hate in the US. Or like, “you [Asians] deserve what you’re getting”. What happened next was quite remarkable. The UN Secretary-General António Guterres issued a statement expressing his profound concern over the rise in violence against Asians, and people of Asian descent. A few days later, on April 1, Sergey Lavrov, on behalf of Russia, kind of made his contribution to the high-level discussions on racial discrimination. Foreign Minister of the Russian Federation, 60 percent of whose territory has historically belonged to ethnic groups of [East] Asian origin, spoke against the aggression towards white people, white US citizens and warned that anti-white racism might be building in America. His statement might appear to be somewhat paradoxical, but it most likely reflects the Russian power’s and public’s attitude towards ethnic and racial minorities not only in America, but in very itself as well.

Thus, the increasing deterioration of the Asian looking peoples’ situation in the Russian Federation and total disregard for this issue being showed by its authorities seem quite understandable given that, as Casey Michel explained in Politico, Moscow’s strategic support for Western nationalist and Christian fundamentalist movements has put Russia, as the number two white power with the United States being the number one, “at the helm of the global Christian right”, and “American fundamentalists bent on unwinding minority protections in the US have increasingly leaned on Russia for support – and for a model they’d bring to bear back home”. That may also account for an offensive stance by some leading Russian politicians and Moscow television celebrities toward Kazakhstan and ethnic Kazakhs.

Moscow is once again using the bogey of Kazakh nationalism

Are there Kazakh nationalists in Kazakhstan and, say, Kyrgyz nationalists in Kyrgyzstan? Probably, they are there, just as in the Russian Federation (and not only there), there certainly are a lot of ethnic Russians, who are used to call Kyrgyz and Kazakhs (as well as Buryats, Kalmyks, Yakuts and other Russian citizens of East Asian appearance) “churkas”, “monkeys” and “animals” or “beasts”. Why can we only talk about the probability of finding those who might be described as the representatives of Kazakh nationalism in Kazakhstan? Because there’s scarcely anyone in the country, who would have proclaimed himself to be a hard-line Kazakh nationalist. Even Kuat Akhmetov, who is now perceived as exactly the kind of person in Russia (and not only there), doesn’t consider himself a nationalist. He stated this in a commentary to Sputnik. “I consider myself [just] a citizen of Kazakhstan”, Kuat Akhmetov said.

Yet almost no one in Russia, and not only there, is going to listen to the relevant arguments of the Kazakh side. Here’s what should also be said. The Kazakh people’s shared historical record has got overburdened with memories of those who had suffered repressions during the multiple campaigns of fighting the so-called Kazakh nationalism. The following is what Zhuldyzai Fort, a Kazakh psychologist, said in that respect: “In the USSR, there probably was not a single other concept, except for one concerning Kazakh nationalism, that would have been discussed so biasedly, distorted so shamelessly and overgrown with such a large number of frightening myths. The Kremlin Soviet demagogues achieved their goal – they managed to turn Kazakh nationalism into a bogey, with which the [Russian] imperials still intimidate the Kazakhs”.

Yet what now are the relations of Kazakhstan’s titular ethnicity with Russians and other Slavs, who live in the country, after what happened during the Soviet period, and in the light of what has been taking place in recent years? It is practically difficult, if not impossible, to give a comprehensive and thorough answer to the question in a few words. That’s a subject which would require separate consideration. But one thing is certain that relations between Kazakhs and Europeans in Kazakhstan are now developing much more harmoniously than those between ethnic Russians and ethnic minorities of [East] Asian origin in the Russian Federation.

What’s next?

Another explanation for this attitude is that the survival of Russia is now believed to be depending on its ability to mitigate serious threats which would come from the Central Asian direction. Moscow is well aware that the changes taking place in Afghanistan are meant to push the process of post-Soviet Central Asia’s becoming part of the (Greater) Middle East. There are two options for the development of events in the Central Asian region. Russia is apparently not comfortable with them both. One of them suggests that the instability in Afghanistan may spill over into post-Soviet Central Asia; while the other is related to the possibility of building railway links between post-Soviet Central Asian nations and Pakistan and laying hydrocarbon pipeline corridors across Afghanistan and Pakistan from post-Soviet Central Asian countries to India and promoting economic and trade ties that would connect Central Asia to markets in South Asia and Europe. There sure is something Moscow need to be worried about. Central Asia, that it has historically viewed as its backyard, is entering a new period. Kazakhstan, which the Russian leadership has been used to consider as the foothold they need to sustain the other four countries of the region under their control, is already economically connected with the West much more than any other nation in the region. The EU and the US account for two thirds of all foreign direct investment in the country. It is becoming increasingly difficult for Moscow to keep the Central Asian giant within its orbit. And this, in turn, makes the prospects for holding the other four republics of the region within Russia’s ‘zone of privileged interest’ vague. The situation has been furthermore aggravated by heavy uncertainties concerning the future of the region as a whole.

With all this in mind, Moscow already is probably thinking not about further keeping Central Asia within its orbit, but about how to isolate Russia from it, having seized the northern part of Kazakhstan first. That is the way it appears. Why else would the Russian media forces open heavy informational fire on the so-called anti-Russian nationalists in Kazakhstan and, in so doing, form a public atmosphere similar to that which was observed in the republic after the December events of 1986?!

In 2015, Vyacheslav Morozov, a professor and political scientist at the University of Tartu, said when and under what conditions Russia could implement a policy of territorial expansion into Kazakhstan.

Here is his forecast: “As long as… open provocations (for example, outright attacks on ethnic Russians by radical nationalists) can be avoided, the Kremlin will not be able to quickly use the concept of a “Russian world” to justify intervention… Even if Moscow decides to use the slogan of protecting “compatriots”, it will have to ensure the mobilization of Russian public opinion against Kazakhstan first. Before launching a massive propaganda campaign, there will be a need to provide the necessary prerequisites for it”.

Those conditions are already there. Only a matter of time seems to remain unresolved. The question is: what’s next?

*Akhas Tazhutov, a political analyst