Possible Expansion Of AUKUS And Implications – Analysis

Introduction

In recent years there has been a plethora of reorganising security architectures in the global security arrangements as localised conflicts and great power competition is on the rise. This trend stems from the fact that national security has emerged as paramount focus in many countries either under direct threat or perceived from a potential threat.

This reconfiguration of the security arrangements are of many forms: bilateral, trilateral, quadrilateral or even multilateral. The Indo-Pacific region has seen several such constructs both in the security and economic domains. The prominent two in the security domain are the QUAD and AUKUS. Both these platforms have become very active in dealing with the region’s security challenges. There have been talks to expand the two groupings by embracing new members. This analysis shall focus only about AUKUS and the compelling factors behind such talks.

Background

The AUKUS security pact, the new three-way strategic defence alliance between the US, the UK and Australia, was formed initially in 2021 to build a class of nuclear-propelled submarines. But the three member countries under the new pact shall also work in the Indo-Pacific region where China’s growing power in the Indo-Pacific region is seen as posing increasing threat. It was felt therefore the need to develop new technologies. This effectively meant that Australia will end the contract given to France in 2016 to build 12 diesel electric-powered submarines to replace its existing Collins submarine fleet. The deal marked the first time the US has shared nuclear propulsion technology with an ally apart from the UK. (1)

Because of the vast expansive operations and activities of China, the threat perceived or real, is being reflected in the policy formulations of many countries in the India-Pacific region to cope with this new challenge. The threat is because of China’s dramatically deepened interests in the region that stretches through some of the world’s most vital seaways east of India to Japan and south to Australia. Australia felt nuclear-propelled submarines have longer range, quicker and harder to detect and thus switched to the US from France for collaboration.

The former UN national security adviser Stephen Lovegrove termed the AUKUS as more than a class of submarine and described the pact as “perhaps the most significant capability collaboration anywhere in the world in the past six decades”. He admitted that the project was “in gestation for some months”. The US president, Joe Biden, is committed to maintain a “free and open Indo-Pacific” and to address the region’s “current strategic environment”. From this perspective, the submarine project gels well in this narrative. Understandably, France was miffed.

France reacted by saying that the decision to “exclude” it “shows a lack of coherence that France can only note and regret”. France’s foreign minister, Jean-Yves Le Drian, was less diplomatic and called the deal “a stab in the back”. In 2016, France had described the Australian contract as the deal of the century and the start of a 50-year marriage. It was intended to symbolise a wider Australian-French alliance in the Indo-Pacific that would extend to weapons intelligence and communications. Australian partnership was also central to its 2018 Indo-Pacific strategy. The cancellation of the contract therefore upset France.

Reactions

There was mixed reaction to AUKUS’ formation globally. Initially talks centred on why two QUAD members – India and Japan – were excluded or even consulted before the formation of AUKUS was announced. Such reservations were soon clarified when it was made clear that it was the collective efforts of the three members to push back against China’s growing power in the Indo-Pacific region.

As expected, China called the AUKUS pact dangerous and warned it could spur a regional arms race. It needs to be kept in mind that the three AUKUS members had already strained relations with China. Though China was not named at the formation of alliance framework, it was clear that AUKUS was in response to Beijing’s expansionism in the South China Sea and aggression against Taiwan. Therefore China’s swift response was not surprising. China’s foreign ministry observed that the three countries were in a grip of an “obsolete cold war zero sum mentality and narrow-minded geopolitical concepts”;

The geopolitical significance of the new defence alliance in the Indo-Pacific cannot be understated. After initial reservations, regional partners such as Japan and India welcomed AUKUS’s formation. Though India greeted the news that AUKUS shall focus on the Indo-Pacific, it was concerned at the same time that the new security alliance may cause an increase in the number of nuclear-powered attack submarines operating in the eastern Indian Ocean from the 2030s onwards. The concern was because the Indian Navy currently does not possess these types of vessels though would like to have. There is no such plan at present. (2)

Why Japan now?

The latest wave of interest in AUKUS has come recently with speculation about Japan’s potential role in the alliance’s second program, known as “pillar 2”. Japan as the world’s third largest economy is just one of several nations that have been considered as potential partners, along with New Zealand, Canada, South Korea and possibly Singapore. Consultations with Japan and other countries as potential collaborators would begin later in 2024. Surprisingly, India despite its rising global profile was not mentioned as a possible another candidate.

Including Japan in this institutional framework is not that easy and challenges could be large for Tokyo. But the three AUKUS members feel since Japan has close bilateral defence partnerships with all three countries, bringing Japan into the framework on the AUKUS Pillar 2 advanced capability projects could be a win-win proposition for all and serve the region’s interests well. (3)

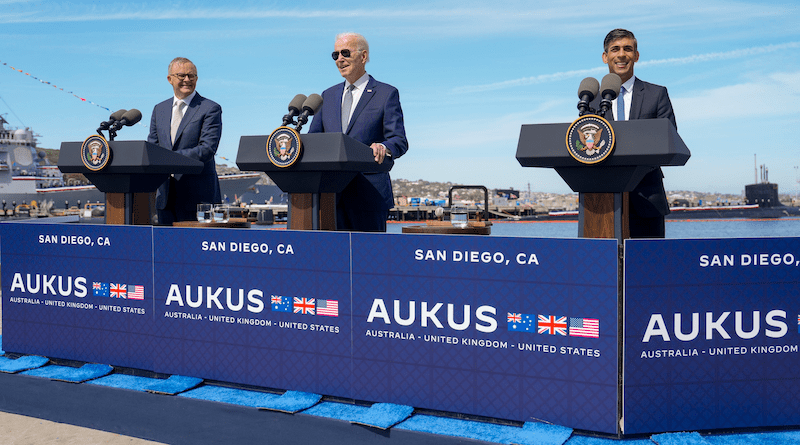

The announcement was made when the leaders of the three countries – US President Joe Biden, Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak – met after a trilateral meeting at Naval Base Point Loma in San Diego, California. In particular, Biden is pushing for Japan to be involved as a deterrent against China. Pillar 2 of the pact commits the members to jointly developing quantum computing, undersea hypersonic, artificial intelligence and cyber technology. The three AUKUS members are not considering expanding the first pillar, which is designed to deliver nuclear-powered attack submarines to Australia. (4)

Because of China’s incursions into the Philippines waters in South China Sea, US President Joe Biden has sought to step up partnerships with US allies in Asia, including Japan and the Philippines. China’s historic military build-up and its growing territorial assertiveness is threatening regional security order and therefore a counter strategy was felt necessary.

As regards co-opting Japan into this security framework, US ambassador to Tokyo Rahm Emanuel was the first to flag Japan as the first additional Pillar 2 partner. As expected, when Biden hosted Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida in Washington in early April 2024, he flagged the issue of Japan’s inclusion in the AUKUS fold. However Australia has reservations. It is wary of beginning new projects until more progress has been made on supplying Canberra with nuclear-powered submarines. Canberra hopes that the AUKUS submarine project could help deter any Chinese move against Taiwan, the democratically governed island that Beijing claims as part of China.

Thus it transpires that the next phase of AUKUS pact envisages deepened cyber-security and naval cooperation with other countries such as Japan, Canada and other Asian partners. For now the focus of the three members shall be on the use of artificial intelligence, drones, and deep space radar to counter China’s aggression in the Pacific. They have also pledged to undertake “a series of integrated trilateral experiments and exercises”, to test and refine the operation of uncrewed maritime systems. (5)

For now, the three members are discussing what assets the allies such as Japan, South Korea and Singapore can bring to the table. It is inexplicable that no leader from any of the three member states mentions India as a potential partner in the group. India might frown at certain point if real expansion happens but remain excluded. UK defence secretary spoke recently about future cooperation between AUKUS partners and other nations but did not mention India by name.

Like Japan’s case, India’s case is too strong to be in the grouping but overlooked. Like India’s stake in the South China Sea and troubled relations with China, and its economy on a steady growth path, Japan too has plenty of stakes in security because of a host of unresolved issues with China, South China Sea, Russia and even South Korea. While Japan has announced to hike its defence budget and breaching its self-imposed threshold of not exceeding 1 percent of the GDP which will make it the world’s third largest, South Korea faces a continuing threat from its northern neighbour and therefore has compelling reasons to maintain a capable military to deter a potential conflict with North Korea. Singapore is considered because it maintains well-trained and hi-tech naval and air forces. Since security guarantee would be the primary consideration, partnering with the Asian countries with common viewpoints on regional issues weight heavily on the AUKUS members’ expansion thought process. This would include enhanced training exercises, joint procurement of advanced weapons systems and stronger collaboration in cyber defence. (6)

Beyond Asia, other countries such as Canada and New Zealand are also in the AUKUS radar. Both are members of the Five Eye alliance with the US, Australia and the UK. What could weigh in Canada’s favour is that it has huge deposits of critical natural minerals. The three AUKUS members can lessen dependence on China by increasing imports from Canada. It is also being argued that if Canada joins the AUKUS fold, its long coastline can be protected by new submarines. Canada has the longest coastline in the world which runs along the Arctic, a region under significant geopolitical scrutiny from a number of nations.

Possible future trend

Considering the developments surrounding the AUKUS, it transpires that AUKUS is a big political call for the three members driven by security considerations. But any expansion or even in its present form carries the seeds of a potential conflict with Taiwan since the three are committed to supply the self-governed islands with weapons. The US has made its position clear by publicly announcing that AUKUS submarines could be deployed against mainland China in any conflict over Taiwan.

Though talks about including new members into the AUKUS fold are doing the round now, there is little possibility of embracing new members in the immediate term unless there is clarity on the conditions of admission and obligations. But if geopolitical and geostrategic undergo perceptive change, collaboration with a range of partners in the Indo-Pacific and North America could be thinkable.

Endnotes:

- Patrick Wintour, “What is the Aukus alliance and what are its implications?”, The Guardian, 16 September 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2021/sep/16/what-is-the-aukus-alliance-and-what-are-its-implications

- “The effect of AUKUS on India’s foreign and defence policies”, vol.28, March 2022, https://www.iiss.org/publications/strategic-comments/2022/the-effect-of-aukus-on-indias-foreign-and-defence-policies

- Jesse Johnson and Gabriel Dominguez, “U.S., U.K., Australia consider working with Japan on AUKUS security pact”, The Japan Times, 9 April 2024, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2024/04/09/japan/politics/aukus-japan-cooperation/

- “US, Britain, Australia weigh AUKUS security pact to deter China, FT says”, Reuters, 7 April 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/aukus-weighs-expanding-security-pact-deter-china-ft-says-2024-04-07/

- https://www.msn.com/en-in/news/world/japan-to-join-aukus-in-expected-expansion-to-deter-china-report/ar-BB1lcf9w

- Andrew Hammond, “How the Aukus alliance can be boosted by Asian partners”, 13 April 2024, https://www.scmp.com/opinion/article/3258584/how-aukus-alliance-can-be-boosted-asian-partners?utm_medium=email&utm_source=cm&utm_campaign=enlz-opinion&utm_content=202