Reflections On Social Exclusion And Radicalization In The Arab World – Analysis

The independences of the Arab nations in the 20th century brought hope to the Arab masses for better living standards and better future but unfortunately this dream never materialised in non-oil countries. Instead, non-democratic Arab governments adopted neo-tribalism practices, and neo-patriarchy philosophy to perpetuate their regimes and consolidate their power on the masses.

These non-democratic regimes gratified their followers and supporters with high positions in the state system and allowed them to use corruption both as a carrot and as a stick on citizens. The spread of corruption practices within Arab countries ultimately destroyed the economy and pushed people’s living conditions to the limits of poverty.

Youth, men and women, on arrival to the job market were astounded to find out that whatever skills they acquired in public school educational system did not allow them to get employment and consequently they became victims of social and economic exclusion and with time they were easily lured by the Islamist sirens that promised them an identity and a purpose in life with dignity. The Islamist master terrorists brainwashed the impoverished and disappointed young people with promises to change their lot through violence legitimated by their brand of Islam.

In this article we will attempt to look at the root reasons of social seclusion and radicalisation of the youth in the Arab world and how governments in Morocco, Egypt and Jordan try to give them hope and means to lead a full and peaceful life with dignity and ambition.

What is social exclusion?

Social exclusion (1) is the marginalisation, the setting aside of a person or a group due to too great a distance from the dominant way of life in society. This process can be voluntary or undergone.

Social exclusion is defined by the marginalisation of a portion of individuals in a society due to different factors and social criteria differentiating them from the rest of the population. (2) For example, disabled, homeless or elderly people may be affected. The contours of social exclusion are difficult to define because its progression is not linear and can occur more or less suddenly, leading to the absence of social ties with the rest of the population.

Social exclusion is often the result of job loss, over-indebtedness, loss of housing, etc. and results in great poverty, in a more or less brutal break with social networks, with social life in general. It is experienced as a loss of identity. (3)

Although often linked, social exclusion is not necessarily juxtaposed with a situation of poverty. The concomitance of the two terms occurs most of the time due to the feeling of social exclusion that long-term unemployment can cause. Active participation and belonging to the job market are in fact vectors of socialization and the almost obligatory maintenance of social ties. (4)

The themes of the fight against social exclusion are numerous because there are many situations which can lead to this relegation from society: fight against food insecurity, strategy for prevention and fight against poverty, access to rights and aid for people in difficulty, access to housing and, failing that, emergency accommodation, promotion of citizen participation, access to domiciliation for homeless people, improvement of conditions for leaving child welfare , maintaining social ties with isolated elderly people, etc. (5)

All these subjects must be the subject of significant and simultaneous treatment in order to leave no one behind and allow everyone to stop the process of social exclusion as soon as possible, before it becomes difficult to do so.

The expression “social exclusion” finds its origins in René Lenoir’s work, Les Exclus, published in 1974. (6) It replaces “social withdrawal”, “maladjustment” or even “poverty”, understood from a pure economic perspective. It is related to a multidimensional meaning, in a socio-economic context where we will soon discover the “new poor”. (7)

In the 1960s and 1970s, this is a concept that does not exist: we simply speak of “social withdrawal” which designates essentially economic poverty, in the process of disappearing due to economic growth and social protection institutions. Since then, poverty has been analysed in a multidimensional way and social exclusion has been better taken into account. (8)

The concept of social exclusion goes beyond that of poverty since it corresponds to the non-realization of basic social rights guaranteed by law. Although social exclusion is a very old phenomenon and common to many societies, the expression appeared in the 1980s to reflect this phenomenon in post-industrial societies.

Within society, exclusion results from several factors: isolation, disability, precariousness. On the street, the situation of homeless people is mainly one of social exclusion. Thus, we commonly consider that homeless people are “greatly excluded”. (9)

The factors of exclusion on the street are well known. Homeless people accumulate relationship breakdowns which lead them to isolate themselves and rejoin the anonymity of the public space of large metropolises. Relationship breakdowns can concern childhood when the children have been orphans, have been placed in care or have had to endure violence. In adulthood, these ruptures concern emotional life and professional activity and can be the consequence of mental pathologies. (10)

Poverty is therefore not only material but also and undoubtedly first and foremost relational since it relates to the social bond which is considered altered. Sharing and solidarity do not make it possible to overcome extreme poverty which is characterized by precariousness and a very widespread phenomenon of exclusion. (11)

Unemployment and social exclusion in the Arab World

A survey released by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) on December 30, 2022 reveals that poverty affects a third of the population in the Arab region, excluding Gulf Cooperation Council member countries (GCC) and Libya.

Titled “Survey on economic and social developments in the Arab region“, it indicates that “poverty, measured against national poverty lines, has increased to affect 130 million people in Arab countries“, predicting a further increase in poverty levels over the next two years, which is expected to affect 36% of the population in 2024. (12)

The survey states the following in its summary: (13)

“As countries worldwide are still recovering from the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine is resulting in severe implications for the global economy. It is driving energy and commodity prices up, and threatening food security in many parts of the world. The magnitude of the impact on individual countries depends on the composition of their economies, and their trade and financial links with the Russian Federation and Ukraine. Arab economies have been significantly affected, some positively and others negatively. While some Arab countries have benefited from spikes in energy prices, others have suffered from rising energy costs, food supply shortages, and drops in both tourism and international aid inflows.”

In addition, notes the survey, the Arab region recorded the highest unemployment rate in the world in 2022, i.e. 12%, adding that this rate would see a very slight decline in 2023 to reach 11.7%, due to post-COVID-19 economic recovery efforts. The region’s economy would record growth of 4.5% in 2023 and 3.4% in 2024, the survey predicts.

According to Ahmed Moummi, the lead author of the survey, the GCC and other oil-exporting countries will continue to benefit from rising energy prices, while countries that import it will suffer from several socio-economic challenges, including rising energy costs, food shortages and declines in both tourism and international aid flows. (14)

In 2022, the International Labor Organization (ILO) estimated that the Arab States will have “the highest and fastest growing youth unemployment rate in the world“, with an estimate of 24.8% for 15-24-year-olds, compared to around 15.6% globally. This average figure is particularly affected by a very high rate among young women (42.5%). (15)

On the issue od youth employment in the Arab world, Mustapha K. Al-Sayyid writes: (16)

“The question of youth unemployment is highly critical in the Arab world, because of its magnitude and growing trend, the grave consequences for economic and social development as well as its potentially politically destabilizing implications. It is a well-established fact that youth unemployment and the quality of their employment were among the major driving forces of the 2011 revolts whose consequences are still felt in Arab countries seven years later.”

The fact remains that across Arab countries, contexts differ and the unemployment rate of 15-24-year-olds varies widely from one country to another. While it approached 40% in Jordan and Palestine, at the end of 2021, it was only 14% in Oman and only 0.5% in Qatar.

In a context where almost one person in three is under 15 and one in two is under 30 and where the population is growing almost twice as fast as the world as a whole, this phenomenon of unemployment risks accelerating and weighing increasingly on national economies. (17)

In addition to national particularities and gender differences in terms of access to employment, spatial data must also be taken into account. Generally speaking, unemployment rates tend to be higher among young people who live in rural areas. (18)

Generally speaking, the problem of youth unemployment in Arab countries is not new. In addition to the lack of economic diversification and the high prevalence of informal work (19) (above 60% on average and up to 85% among those under 25), it is the excessive dependence on the public sector that is called into question.

On the prevalence of the informal economy in countries of the MENA region, Hamza Saoudi writes: (20)

“The informal sector plays a major role in most MENA economies. It employs a large share of the total population and, on average, accounts for about 22% of GDP. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), which defines informal employment as the proportion of workers without access to social security, the share of informal employment in total employment in MENA countries ranges from 45% in Jordan to 80% in Morocco, with intermediate values of 59% in Tunisia, 63% percent in Egypt, 67% in Iraq and 70% in Syria.

In all MENA countries, informal employment is most prevalent in the agricultural sector, followed by industry and the services sector. The prevalence of informality in total employment in the agricultural sector ranges from 69% in Jordan to almost the entire workforce in countries including Yemen, Egypt and Syria. In industry, informal employment ranges from 57% to 83%, and in the services sector, from 38% to 73%.”

In its report, “The Jobs Challenge – Rethinking the Role of Government towards Markets and Workers in the Middle East and North Africa Region,” the World Bank estimates that almost half of workers in Iraq are employed in the public sector, while it is one in four people in Jordan and Egypt. (21)

The political context with the region’s various socio-economic disruptions and conflicts are also factors that prevent governments from implementing policies to create stable and decent jobs for their young population.

On the situation of employment in the Arab World after the Arab Spring, the World Bank points out: (22)

‘’ A decade after the first spark of the Arab Spring, large shares of healthy and capable working-age populations remain excluded from the labor force and employment altogether in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. This is most evident for youth and women. Nearly 1 in 3 youth (32 percent) aged 15 to 24 in MENA are not engaged in employment, education, or training (NEET). The youth unemployment rate in MENA is the highest in the world—estimated at around 26 percent (as of 2019)—and has been persistently so for the past two decades. The share of employment that is informal (defined as lacking social security contributions, whether for pensions, disability, sickness, or other risks) varies within the region but remains notably high. The share of informal employment is estimated to be as high as 77 percent of total employment in Morocco, 69 percent in the Arab Republic of Egypt, and 64 percent in West Bank and Gaza, and as low as about 16 percent in Bahrain. Restrictions on women in the labor market also persist.’’

However, Arab women seem to be the most affected by unemployment in this region according to the same World Bank report: (23)

‘’The lack of inclusivity in the labor market in the Middle East and North Africa is most apparent in the plight, and lost potential, of women. One of the mainstays of the MENA region in terms of labor market outcomes is the lack of tangible and notable changes to the situation of its women. Female labor force participation, averaging about 20 percent, is still the lowest in the world. However, younger, and better-educated, cohorts of women are increasingly more likely to want to enter the labor market (Arezki et al. 2020).’’

Ensuring decent work opportunities in the Middle East and North Africa is undoubtedly ensuring long term stability. (24) It must be said that unfortunately the Arab Spring promise of better political, social and economic future for the Arab masses welted miserably ten years later. (25) Governance is as bad as it was before, political participation and accountability are back to square one. The youth are still marginalised and excluded and women discriminated against and ostracised by religious dogmatism. This continuous exclusion of the youth, which forms the majority of the population in the Arab are pushing this fringe into the arms of Islamists and leading to radicalisation. (26)

Anger in the Arab streets because of political, social and economic exclusion

Most Arab countries, with the exception of the Gulf States, have staggering rates of economic exclusion of the youth. As such, youth unemployment is the highest in the world. The lack of prospects for millions of young Tunisians, Egyptians and Yemenis favoured the revolutions of the Arab Spring in 2011. (27)

No Arab country is immune of social unrest, because most of them have the same explosive ingredients, notably a sclerotic and repressive political system, widespread corruption and a fed-up with a blocked situation at all levels.

Intellectuals talk about the “‘Tunisianization’ of the Arabs”. However, the real shock wave of the Arab Spring translated differently. There is a real risk of Islamization of the revolt in Libya, Bahrain, Yemen or a risk of regionalisation in Algeria or Yemen. In Algeria, the situation is exceptionally complex. The trauma of ten years of civil war is very strong. In addition, the State has deployed occult relays in all levels of society in a degree that does not exist anywhere else. However, these relays which can be perceived as opposition considerably disturb the game and hinder the emergence of organized dissidence. (28)

It seems that in monarchical countries royalty is not threatened at all. In Morocco, for example, there is an aspiration for change, however the monarchy enjoys real support. In Bahrain, royalty is not in question as such, but there is a demand for equal treatment for the predominantly Shiite society governed by a minority Sunni dynasty. There is also no desire to overthrow the monarchy in Jordan. (29)

Conversely, the dynastic temptation of authoritarian regimes, within which the president monarch organises the transfer of power to his descendants, is the direct target of the protest whether it is Gamal Mubarak, (30) considered until recently as the son heir of the former Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak, or today of Seif Al Islam, son of General Gaddafi, who promised a bloody response to the revolt. These practices of confiscation of power by descendants are today condemned by Arab masses. (31)

By setting himself on fire, the young Tunisian, Mohamed Bouazizi, unknowingly lit the fuse of political protest and quickly became the symbol of Arab youth without professional prospects, in countries where those under 25 often represent more than 40% of the population.

From Morocco to Iraq, all Arab nations are experiencing high growth in young people aged 18 to 25 entering the job market, although it is now decelerating, especially in the Maghreb. However, the economies of these countries are incapable of creating jobs adapted to meet demand.

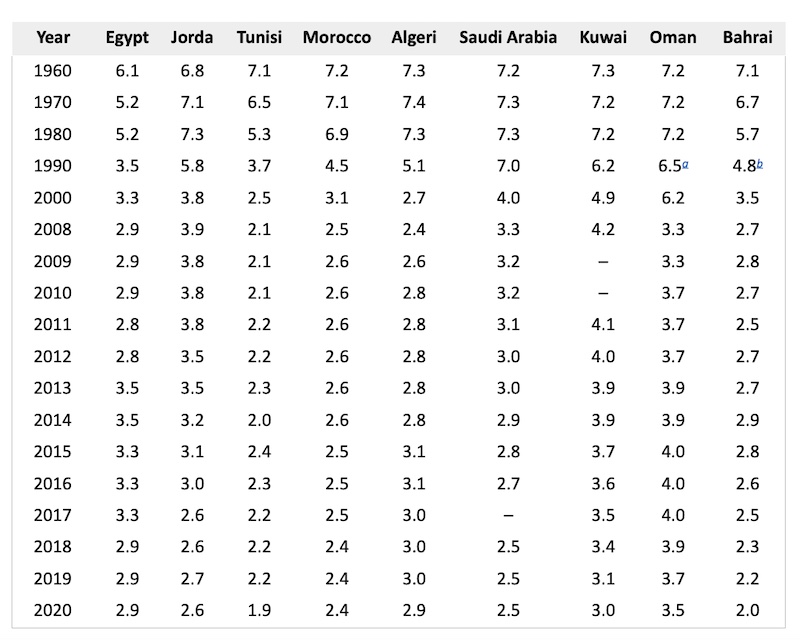

The birth rate has fallen sharply in the Arab world, even if there are large disparities between Tunisia, where the fertility rate is comparable to that of France, and Yemen, where families of five children remain the norm. Some countries have completed their demographic transition and are moving closer to Europe, while others are on the way to achieving it. The Arab world is experiencing a process started by Europe in the 17th century. Boys, then girls, emerged from illiteracy. They studied and more and more went to the university. We have witnessed the rise of the anti-establishment spirit and the secularisation of society, but also the questioning of parental authority and religious authorities.

However, the Arab Spring revolutions are not strictly speaking youth revolutions, all social strata marched in the streets. Among the slogans heard on Arab streets there were numerous complaints against the high cost of living and very low wages. The Arab world has seen the emergence of a very educated class, but which has not been able to take the social elevator, due to the lack of qualified jobs.

Worse, the middle class of these countries which had emerged in the aftermath of decolonisation saw its purchasing power crumble. For example, the children of civil servants pampered by Nasser in Egypt in the 1960s did not find opportunities despite their diplomas, moving up a notch in the social ladder. In Egypt, nearly 40% of the population lives on less than $2 per day, below the poverty line set by the United Nations. In Tunisia, the purchasing power of teachers and lawyers, affected by the rise in prices, particularly of raw materials, has fallen by 10 to 15%.

Inequalities, corruption and illegal sources of enrichment partly explain the protest movements observed in several Arab countries. These states are among the most unequal in terms of resources per capita and the least transparent on the annual corruption index established each year by the Transparency International association. The administrative apparatus is corrupt. (34) The citizen cannot file an appeal with the courts. He cannot defend himself, so much so that he sees the system as a machine organized to impoverish him.

At the same time, the population is observing the enrichment of a minority close to power, which is taking advantage of waves of privatizations or sales of state estates to monopolise land, buildings and businesses. If salary differences remain moderate, there are strong inequalities in terms of assets. However, tax policies do not allow for a redistribution of wealth. Taxation remains low, in fact, in the Arab world, compared to Europe. For example, income tax is capped at 20% in Egypt. (35)

In this regard Mario Mansour and Eric M. Zolt argue: (36)

“Personal income taxes (PITs) play little or no role in the Middle East and North Africa, often yielding less than 2 percent of GDP in revenue—with the exception of few North African countries. This paper examines how PITs have evolved in recent decades, and what they might look like in the next 20 years. Top marginal tax rates on labor and business income of individuals have declined substantially, a trend that mirrors reductions in advanced and developing economies. Taxation of passive capital income has changed very little, and the revenue intake from this source remains low throughout the region (less than 1 percent of GDP on average and concentrated in oil-importing non-fragile states). Social security contributions (SSC) have increased in importance in nearly all MENA countries, and some countries have introduced additional payroll taxes.”

Oppression and the absence of fundamental freedoms, particularly of expression, are the essential and common cause of the revolts which shook the world Arab. In Tunisia as in Egypt and in other countries crossed by demonstrations, this situation, common to all social strata, creates a unified movement. (37) Disadvantaged young people, individuals from the middle classes, unemployed graduates meet with the same aspiration for freedom and dignity. The entire Arab world is crossed by this deep desire for human rights and democracy; people are ready to die for that common basis translates differently in each country. (38)

The inhabitants of the Arab world, by looking at the rest of the world, have become aware of the importance of citizenship, of the individual. They saw elements of modernity under the control of retrograde, conservative regimes. Hence a frustration which was expressed in the streets. People decided to break down the locks to open a new page, that of freedom. Moreover, it is perhaps no coincidence that it is in Tunisia that the groundswell began because Ben Ali’s regime was a model of repression and population control.

The media, electronic in particular, are a sounding board for frustrations of people. The connection between online and offline movements is decisive. The Web is a catalyst. The Internet created trust thanks to its unifying power which helps to consider oneself as part of a mass movement. On the Internet, people have become contributors. When they support an initiative on a social network by clicking on “like”, it’s the start of an action. (39)

The wave of protest did also spread by word of mouth. In Egypt, demonstrators called their friends to join them by SMS. They underlined the force of images on television – the Al-Jazeera channel wass covering the demonstrations – or on the Internet which reinforced the street anger. Finally, the media promoted greatly the revolt in the Arab world.

On the strength of media in igniting the Arab Spring Zahera Harb writes: (40)

‘’The Arab world was taken by surprise when mass protests erupted in Tunisia in December 2010, followed by mass protests in Egypt in January 2011. Much optimism was expressed towards a new era for journalism freedom in the Arab world, in Egypt specifically with the fall of Hosni Mubarak and the long reign of his authoritarian regime. The influx of private media mainly TV channels following his demise was remarkable. Seven years on from the Egyptian revolt, the state of journalism in Egypt has transferred from a state of hope to one of despair. When assessing the state of Arab journalism, two countries come to the forefront: Lebanon – a plural and diverse model but still bound by confessional system (entails distributing political and institutional power proportionately among different religious sects) and ideologies – and Egypt – the largest country in the Arab world in terms of population and area, and a country of media freedom contradictions post-Arab uprisings with general tendencies among journalists to express loyalty to those in power. Two of the main challenges that face journalists in Egypt and Lebanon post Arab revolts are safety and job security. These challenges were mirrored in 30 in-depth interviews I conducted with journalists across platforms in both Egypt and Lebanon in 2016 and 2017.”

Neo-tribalism

Neo-tribalism (also called modern tribalism) is a sociological concept which postulates that post-modern society is characterized by a return of tribal philosophy, and by a decline of individualism in communities. (41)

Ibn Khaldun’s thought is a prodigy of illuminating aporias. But it’s an even more prodigious thought for modern Westerners, whose political principles stand in violent contrast to those Ibn Khaldun took for granted. Ibn Khaldun was always scandalous, but unlike so many of the provocateurs of yesteryear, he is even more scandalous than he was ever aware of being.

The State and tribes are discussed at length in his work. While we are accustomed to opposing the two terms, it is one of the great merits of Ibn Khaldun’s theory that it makes us understand that one does not go without the other: the accumulation of wealth and human resources, of which the State is the natural creator, engenders the existence of the tribe as surely as the multiplication of prey favours the rise of predators. The State’s security needs lead it to arm tribes and entrust them with its defence. If our world is to see the rebirth of tribes, it is precisely because the State holds, and will continue to hold, a central place in it.

If democracy never took root in the Arab world after the Nahda (42) it is because the political systems that occurred after this event never adopted the European nation-state philosophy instead, they encouraged the narrow approach of tribalism with all its trimmings especially the famous concept insor akhak daliman aw madlouman انصرأخاكظالماأومظلوماwhich means ‘’ always defend your kin whatever the circumstances.” (43)

In explaining the dynamics of neo-tribalism, Dale C. Spencer and Kevin Walby argue: (44)

“Neo-tribes or micro-groups are the result of a feeling of belonging and a specific ethic that is formed within the framework of a communication network (Kelemen and Smith, 2001; Maffesoli, 1996: 139). While the group is enjoyed for its own sake, it allows for mutual aid where specific personas fulfill their roles in the aid processes. The neo-tribe also has a tangible, spatial element, insofar as proxemics consist of spatial relations where cooperation and conflict can happen.”

The post-independence regimes of this part of the world certainly revamped the old governance, which was totally tribal, to a more subdued version which is called neo-tribalism. As such pan-Arabism though it was a movement meant for the whole Arab world, a large geographical region, yet it derived its force from local tribes; Thus, the Egyptian Gamal Abdennaser had his tribe behind, so did Hafid al-Assad in Syria, Gaddafi in Libya, Saddam in Iraq, Ali Saleh in Yemen, Bourguiba and later Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali in Tunisia, Boumeddienne in Algeria, etc. The monarchies, by definition, were all tribal in their gist and contours. (45)

Neo-tribalism (46) was one of the reasons of the revolution of the Arab youth during the Arab Spring but the counter-revolution (47) that took place silently and insidiously after in many countries brought back to life this tribal phenomenon as well as all the practices related to it such as: nepotism, corruption, mismanagement, patriarchy, etc. (48)

On the issue of tribalism in the Middle East, Faleh A. Jabar writes: (49)

“The reconstruction and state manipulation of tribes and tribalism are prominent features of contemporary Middle Eastern politics, notably in Jordan and Iraq. Under the totalitarian Ba’thist regime in Iraq, two major patterns have developed. One may be called etatist tribalism — a process in which tribal lineages and symbolic culture were integrated into the state to enhance the power of the fragile elite. This process was exclusive, promoting certain Sunni Arab clans and relatives of the elite. Etatist tribalism began in the 1970s and continued into the early 1990s. The second pattern, social tribalism, signifies the regime’s loss of potency in a restless mass urban society. Sensing its weakness due to the impact of war and sanctions, the state devolved functions such as judicial powers, tax collection and law enforcement to the resilient local tribal or kin networks it detected. When so manipulated, reconstructed tribal groups act as an extension of the state. Unlike etatist tribalism, social tribalism has been broadly spread across Iraq’s communal and ethnic divides. Manipulation allowed the state to rally Kurdish and Shi’i tribal groups against Iranian soldiers from 1980-88, in the case of the Shi’a forestalling potential solidarity with their co-religionists from Iran. Both etatist and social tribalism have roots in the persistence of tribal culture in the urban social spaces where migrant segments of disintegrating tribes and clans now live.”

Islamism recuperates marginalised youth by offering them identity and purpose in life

The notion of Ummah refers to the concept of a global community of Muslims who are bound together by their faith and religious beliefs. It emphasizes the unity and solidarity of Muslims regardless of their nationality, ethnicity, or cultural background. The Ummah is seen as a collective entity that transcends geographical and political boundaries, and it plays a significant role in shaping the identity and sense of belonging for Muslims around the world. (50)

For the doctrinaires of radical Islamism, religion must allow to bring together all the states making up the Muslim world into one unique community; a nation of faith (Ummah أُمَّةُ) whose basic principle is the solidarity and whose unifying cement is adhesion-submission to “Rights of God”. (51) In their eyes, the rebirth of the Muslim world is only achievable by resourcing the prophetic model and by the institution of the “sovereignty of God”, not by the importation of European parliamentary model: the Ummah cannot remain fragmented; (52) no entity which composes it could obey the modern content of the Nation (“community of destiny”, defined by its territory, by the sovereignty of the people, by citizenship, by democratic government or by universal suffrage…). (53)

The definition of identity which arises from this conception is of totalitarian essence. Even for Islamists who have abandoned the illusion of pan-Islamism, Ummah has only religious content. In their eyes, religion is the only structuring principle of identity, the central pivot of the political organisation and the social structure, the exclusive foundation of the government of the city and the ultimate basis of authority. (54)

This temptation to submit the whole of society to the ideal of an absolute and total vision of revelation, and to impose the application of scrupulous adherence to the precepts of the Sharî’a in all aspects of existence (ethics, legal standards, social and political system, private life and family, cultural practices, etc.) lead to the refusal of any space autonomous policy, with its specific laws, its positive law and its own values.

The individual is only one element of an entity which exceeds and over which he has no control; man is not considered as a home of freedom or as an autonomous and creative subject; he cannot live and realise himself outside of the group; his free will, his self-will are denied; enclosed within a structure “holistic” and hierarchical community, it has no value in itself. It is withdrawn into “absolute divine transcendence”, he cannot claim his rights; arising from a “divine decree”, human freedom is in no way left to the decision of men. (55)

The strong notion of identity and belonging to the Ummah is explained by Tariq Ramadan in the following terms: (56)

“The individual affirmation of Islamic faith by means of the shahada and the recognition of the family as the first context of social life are the prerequisites for entering into the second circle of social relations in Islam. Each of the four practical pillars of Islamic religious practice has a double dimension—individual and collective. By trying to excel in the practice of their religion, Muslims are immediately called to face the communal dimension of the Islamic way of life. Most Qur’anic injunctions are addressed to the believers in the plural: “O bearers of the faith…” and when Muslims recites the “opening chapter” of the Qur’an (al-Fatiha) in each prayer cycle, they present themselves as members of a community by saying: “You alone we worship, to You alone we turn for help. Guide us in the right Way.”

Just as there is no room here for a theory of the autonomy of the person and the freedom of the subject, nor for a modern and secular definition of juridical-political rights, likewise, any idea of plural content of identities individual and collective and any open conception of identity, are absolutely denied. In both cases Islamists favourable to ‘’Pan-Islamism”, (57) or supporters of “Islamic-nationalism”, adopt an intolerable closure to modern culture and a conception of pathological identity. (58)

“Political Islam” (59) reflects a hegemonic desire based on taking control of all areas of social life through religious “soft power” based on indoctrination. As for Islamism it is a phenomenon which is in fact not recent in the Arab World, and which can be explained by both exogenous and endogenous factors. (60)

On the one hand, the “Islamization of Islam”, a real ideological offensive which has led, under the influence of international geopolitics, to a takeover of this religion by the most militant currents carrying a radical vision. On the other, a favourable breeding ground in society, especially among populations who are often socially marginalized, economically fragile and less well culturally assimilated, but also among rather well-integrated individuals. (61)

This explains why, on a social and political level, Islamism can be particularly difficult to grasp in its complexity. Islamism is an exacerbated politicization or ideologization of Islam. The individual and collective actors who are part of this trend are driven by an ideal: that of founding a social order based on the primacy of religious categories. Their modes of action are plural. (62)

Islamism is in essence a transnational movement. Islamism, which designates political Islam, appeared with the birth of the Muslim Brotherhood (63) الإخوان المسلمون in Egypt in 1928 with the school teacher and thinker Hassan al-Banna (64) حسن أحمد عبد الرحمن محمد البنا. At the international level, the year 1979 marked a decisive turning point, with the concomitance of significant events of a shift in the Muslim world: the hostage-taking in Mecca by Islamists, demonstrating that no place, even the most sacred , was not sheltered for jihadists; the Iranian revolution resonating as an extremely powerful psychological victory for Islamist ideology and demonstrating that the success of a political project was possible; the start of the war in Afghanistan which rehabilitated contemporary jihad against the Soviet Union; then, later, the assassination of Egyptian President Anwar El Sadat, peacemaker with Israel, in 1981. (65)

Islamism, which was, in the 1960s and 1970s, an exogenous threat, became an endogenous threat in the Arab world from the 1980s. It was also at this time that, at the level, pressure, intimidation and threats from supporters of political Islam began, like the first fatwa launched by Ayatollah Khomeini against Salman Rushdie. The term salaf refers to the origins of Islam and means “ancestor”, meaning those who are closest to the message of Mohammad. It is an Islam immersed in an imagination of early times, characterized by violence and conquests. By identification, those who commit violent acts today think that they are legitimized by this frame of reference. Contemporary Salafists thus manage to superimpose the original text and the current context. (66)

The refusal of democracy is most often manifest among violent radical Salafists. (67) They stand out in this in comparison to the Muslim Brotherhood and a part of political Salafism who do not hesitate to play the game of the ballot box as in Egypt, Palestine or Tunisia. This rejection, almost unanimous is of course philosophical. Wanting to replace God with the people as a source of legitimacy and identity, weakens the divine presence and tarnishes his message. (68) The argument is also practical, based on the supposed observation of a chronic deficiency of democracy, incapable of meeting the needs of believers. Fragile, weak and corruptible, democracy yields before the force of the divine word, always just and right. Finally, the argument is political when democratic experiences in Islamic lands are mentioned, rarely satisfactory and a source of discord and disagreement and led by a political class that is by nature predatory and untrustworthy. (69)

Radicalisation of the population as a result of endemic poverty

Political-religious radicalism (70) is now making a comeback, giving rise to new forms of extremism. In its first version, it is based on exploited beliefs and ideals, in the name of which acts of violence are sometimes committed. Their dramatic current events show us the need to question their socio-economic, socio-political and socio-cultural sources. (71)

Apparently, since the attacks of September 11, 2001, the world has entered a new era, that of globalized vulnerability. Indeed, since this horrible shock, the number of terrorist attacks has never stopped increasing and in such a worrying manner that the phenomenon is now considered to become a major geopolitical issue for the entire world.

On the rise of radicalism in the Arab World, Anja Wehler-Schoeck argues, quite rightly: (72)

“The last decades of the 20th century saw a continuous rise of radical Islam. The year 1979 marked the start of a new era with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, which led to Jihadis joining the Mujahideen from many Muslim countries around the world. With the establishment of Al Qaeda at the end of the 1980s, the first terrorist network was created, which no longer limited itself to attacks in specific countries or regions but developed a global aim. This rise of radical Islam can be attributed to a multitude of factors. Among them are the search for identity and recognition, the feeling or experience of marginalization – both politically and economically, opposition to secular nationalist ideologies, frustration with regimes that are perceived as apostate and corrupt, the weakness of educational systems, only to name a few. Several war-torn countries, where the state has lost control of part of the territory, have served as virtual breeding grounds for terrorists, such as Afghanistan, Somalia, and more recently Iraq and Syria. Terrorist groups have also improved their mechanisms of propaganda and recruitment.”

In this context of manifest fragility and with the permeability of borders and the transnationality of religious actors, religious extremist ideologies – and particularly those claiming to be Islamic – are gaining ground and attracting more and more young people, compromising thus the future and security of all the nations that populate this world. Vigilant observers then point to the rise on the scene of an obscurantist Islam which incites hatred and intolerance. They point out that these retrograde, even radical, versions of Islam are gaining ground. Other analysts believe that the financial and doctrinal penetration of Salafism – “a fundamentalist school of thought advocating a return to the original forms of Islam”– threatens the stability of the world. (73)

In fact, the terrorist acts of Islamists bring new figures of violence to the forefront of the media and political scene and thus establish a link with the idea of radical or radicalization as a sort of obvious fact.

The word “radicalisation” comes from the Latin radix, which means “to go to the root”. (74) In a political sense, the term refers to people wishing to radically change society by using – or not – violence. Being radicalised is not just about contesting or refusing the established order. Jihadist radicalisation is driven by the desire to replace democracy with a theocracy based on Islamic law (Sharî’a) using violence and weapons. It therefore presupposes the adoption of an ideology which provides a framework of life and benchmarks guiding all behaviour. Radicalised people divide men and women into two categories: those who adhere to their cause and those who do not share it and are, as such, called to die. (75)

On the political level, the concept of radicalisation then takes on a form of rupture and/or opposition to the national, subnational or supranational political order with, as a corollary in a first phase, self-isolation and rupture of followers towards their own society – which leads them to see as “enemies” groups and individuals outside their sectarian political organization or having an attitude contrary to the one they have adopted. (76) In a second phase, it is above all the behavioural turn by which the so-called “radicalised” subject places religion or ideology in opposition to the values of his own society which makes the notion of “violent extremism” operational. This stage describes a process of switching towards terrorism or the use of violence against one’s own community or others deemed different or in opposition. (77)

Sociologically, radicalisation could be defined as a process of sectarian rupture with the original socio-cultural group: from the family to the territory or country, via the community.

Prison can constitute the scene of radicalisation according to a number authors. Thus, Michel Fize notes that it is one of the oldest places of radicalisation. In 1970-1980, in Italy, “the recruitment of Brigadistes (reds) took place within penitentiary establishments”. (78) In the 1990s, he also mentioned, many members of the Islamic group of Algerian armed forces (GIA) who were indoctrinated in prison. If the prison was an important place there is ten years, “it seems to be less so today”, according to him. (79)

For a former Egyptian activist and political prisoner with the pseudonym Joe Carlos, Egyptian prisons are real incubators of radicalisation: (80)

“Tens of thousands of Egyptians have been arrested since the military took power on July 3, 2013, some having no political activity. But in prisons they have fallen prey to the Islamic State organization which seeks to recruit them, while the Muslim Brotherhood’s discourse is perceived by many of them as too moderate.”

More and more researchers consider that currently the prison is more of an accelerator of radicalisation than a place of radicalisation as such. Thus, Farhad Khosrokhavar shows that prison plays a role essential in the jihadist trajectory of young people from the suburbs: (81)

“…not so much because it radicalizes us but for the fundamental reason that it offers the opportunity to develop hatred of the other in daily relationships of tension and rejection in the face of the prison institution.”

Céline Béraud et al. (82) note the intensification of religion in prison, for all faiths, more than one radicalisation, in particular because religion can constitute a resource allowing better to endure detention.

Patriarchy

The term “patriarchy” typically refers to the concept of a social system in which men hold primary power and predominate in roles of political leadership, moral authority, social privilege, and control of property. It is often associated with the oppression and marginalisation of women and non-binary individuals. The patriarch occupies a mythical position of “founding father” supposed to grant him authority and rights over the people dependent on him (wife(wives), children, extended family, subordinates). (83)

Patriarchy is a tribal value which is still very strong in the Arab world. The concept of individual free from tradition is still very fuzzy because the notion of community is much stronger in traditional systems and this strengthens further patriarchy. The individual has no voice and no opinion per se, he delegates that to the patriarch of the extended family. In return the patriarch rules the family and does not accept any form of contestation or dissent. As a matter of fact, contesters and dissenters are rejected from the extended family and consequently from the clan and the tribe. (84)

Modern political systems in the Arab world after independence adopted happily the patriarchal system. The head of state is chosen not elected or, in some cases, he arrives to power on a tank, symbolising brute power not to be contested. As such he becomes the father of the nation (the patriarch) and the leader of the country zaim زعيم. With time the notion of zaim became a symbol of political sacredness and gave patriarchy more relevance and power. One of the most famous zaims of the Arab world is undoubtedly Gamal Abdenaser because he nationalised the Suez Canal and as such defied European imperialism. (85)

On the concept of Za’âma زعامة/ leadership in the Arab World, Zaid Oqla Alqhaiwi, Timothy Bednall, and Eva Kyndt write: (86)

“While leadership is one of the most studied areas among organisational scholars, research interests in the impact of cultural values on leadership perceptions and behaviours remains ongoing. In fact, most studies adopt a universal or rather Western viewpoint on leadership. As such, the literature is largely unaware of the cultural differences in leadership perceptions, such as those in the Arab World. Drawing on implicit leadership theories (ILTs), our study aims to develop and validate a research model in which Islamic leadership principles (shura, al-amanah, and itqan) and Arab tribal values (ayb, wasta and karam) are associated with leadership behaviours. Data were collected from 544 managers from Jordan and analysed using structural equation modelling. Based on our findings, we present empirical evidence detailing how cultural values are related to leadership behaviours. Results show that Islamic principles encourage relation and task leadership orientations, but negative practices derived from the Arab values of ayb and wasta provide obstacles.”

Country cases of social exclusion and their efforts to circumvent it

Morocco

Marginalisation in Morocco is seen as a process in which certain deviant attitudes, ideologies, values, practices and beliefs are “excluded” from society, due to their contrast with hegemonic procedures. Thus, the notion of “marginality” refers to a state of poverty, deprivation and subordination, but this notion can extend and also include economically well-off people, in the political sphere, in the field of lifestyles or in their social position as members of a particular group in terms of age, gender, ethnicity, religion, political outlook, social class or sexual orientation. (87) Consequently, marginality is not limited to material considerations, but it also results from institutional policies with, on the one hand, protection measures which are insufficient in relation to the scale of local social demand and, on the other hand, violent practices and penalisation measures. (88)

Terrorist attack of 2003

Four days after killing 26 people in attacks on the Western buildings in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, Al-Qaeda strikes Morocco. On the night of May 16, 2003, 14 terrorists launched suicide attacks on different hotels, restaurants and community centres in Casablanca. They are mainly directed against Jewish properties. Their perpetrators are young people from the Sidi Moumen slum in Casablanca, who are members of Salafia, a terrorist group affiliated with Al-Qaeda. The bloodiest attack occurred in the Casa de Espana restaurant, where several customers were eating dinner or playing bingo. In all, 12 of the 14 terrorists were killed along with 33 other people, including eight Europeans. (89)

The attacks of May 2003 are the most serious acts of terrorism in the history of Morocco. They will notably have a negative effect on tourism, one of the country’s main industries, which encouraged the authorities to react promptly. A week after the events, Parliament adopted a law extending from 8 to 12 weeks the maximum period of detention of a person without appearing before a judge. The authorities quickly made more than 200 arrests. In the following months, the Moroccan government used a broad definition of terrorism to convict hundreds of people suspected of belonging to terrorist cells. Many are held in secret for weeks and subjected to torture. Three will confess their links with the terrorists of May 16, after trials which are not considered fair. (90)

These attacks were perpetrated by the marginalised young people coming from the slums of Sidi Moumen in Casablanca. In 2003, Casablanca was surrounded by a belt of slums of people who migrated from countryside as a result of many years of drought in the 80s and 90 of the last century with the hope to get a job in the economic and industrial hub of Morocco, but they could not and became a marginalised population. To feed their families they versed in petty crime mainly selling drug and theft. Later in the beginning of the third millennium they were recruited by master terrorists affiliated to al-Qaeda who brainwashed them in the relevance of Islamist religious identity, provided them with generous funds before sending them in 2003 to die in the name of jihad against the Jews and the modern Crusaders for the sake of Allah and that their death will lead them to eternal paradise. (91)

Adolescence is a period of metamorphoses which play out on the level physical, psychological, intellectual, etc. These adolescents from the slums of Sidi Moumen were, no doubt, explorers of experiences. By seeking a taste for risk and extremes, they surely flirted with death. They did not realize that they were “playing suicide bombers”. Indeed, some of them, changed their minds the last minute and as such did not set off their kamikaze bombs and did not become “martyrs”. (92)

This terrorist attack was immortalised in a film entitled: “Les Chevaux de Dieu (93) ياخيلالله/The Horses of God”, a Moroccan film directed by Nabil Ayouch and released in 2012. The film is inspired by a novel of Mahi Binebine, The Stars of Sidi Moumen, which evokes the terrorist attack of May 16, 2003, in which five suicide attacks bloodied the city of Casablanca, causing the death of 45 people, among them the bombers.

Fighting exclusion and radicalism

1.The IDMAJ Foundation for Development:

It was created in 2006 by Mr. Boubker Mazoz, founding president of the Moroccan association Casablanca-Chicago. IDMAJ was created in response to an urgent need to provide communities with a cultural space dedicated to children in difficulty and provide necessary help to marginalized youth.

The choice to begin actions in Sidi Moumen (94) was justified by the extent of poverty in this district and the lack of infrastructure to support initiatives to protect and develop young people at risk. Sidi Moumen is one of Morocco’s most overpopulated neighbourhoods, home to one of the country’s oldest shantytowns. A poor and marginalised neighbourhood in the past, whose area covers 45 km² and whose population exceeds 500,000 inhabitants. Sidi Moumen was also the place of residence of fourteen suicide bombers involved in the Casablanca bombings of May 16, 2003.

IDMAJ is one of the first associations to become aware of the dangerous socio-economic context of Sidi Moumen which constitutes a threat to the social peace of Casablanca and Morocco in general. IDMAJ recognises the complexity of the issues faced by the community of Sidi Moumen (and especially by its youth), such as precariousness, social exclusion and violence.

This foundation strives to protect young people from violence, victimisation, delinquency, drug abuse and extremism through the achievement of the following seminal objectives:

- Combat delinquency, marginalisation, addiction and extremism;

- Strengthen a youth citizenship development model through youth-to-youth mentoring;

- Teach civic education through action and successful models;

- Encourage schooling and provide tutoring to decrease dropout and failure and increase graduation rates;

- Educate youth and children on the role of personal development and education in the evolution of a healthy and civic-minded community;

- Encourage the participation of IDMAJ members in the organisation of cultural, educational, economic, technological and sports activities;

- Involve the individual and collective efforts of the population to improve the quality of life of their community; and

- Encourage citizens to take responsibility for their actions in their own neighbourhood and communities.

In 17 years of existence, IDMAJ has achieved quite a lot: (95)

- 1500 youth beneficiaries annually;

- 120 volunteers engaged annually;

- 45 staff members;

- 4 community centres operated;

- 150 women beneficiaries annually;

- 30 partnerships with public and private sector;

- 25 programs and projects currently offered; and

- 85% of youth beneficiaries who complete IDMAJ programs.

2. The Touria and Abdelaziz Tazi Foundation: L’Uzine

The Touria and Abdelaziz Tazi Foundation is an association created in June 2013 to promote creation and culture through patronage actions: development of a multidisciplinary cultural space – L’Uzine -, residency program, productions, subsidies, etc. It is located in Casablanca, Morocco. (96)

The Foundation supports artists, cultural and artistic actors as well as cultural projects linked to youth but more broadly to audiences in their diversity. It is committed to promoting cultural life and the dissemination of artistic creation, to encouraging contacts between artists and audiences and to promoting the diversity of forms of cultural expression.

The Foundation, moreover, by strengthening its activity and developing partnerships, aims to become a major player in the promotion and dissemination of creation in Morocco. It supports artistic projects in several disciplines: music, dance, theatre, documentaries, short fiction films, comic strips, photography, graffiti, etc.

Alternative, urban and contemporary creations are at the heart of the Foundation’s action, also convinced that development through culture also involves the recognition and promotion of traditional arts and heritage.

Its values revolve around:

- Culture is a right for all;

- Culture is a vector of social bond and citizenship;

- Artistic expression is free;

- Culture is a means of appropriating the city;

- Cultural diversity is a wealth; and

- Culture allows an opening to the world/worlds.

The Foundation is a centre that offers young people the opportunity to develop cultural products such as comics, graffiti, theatre workshops, or musical performances. However, this cultural centre is a metaphor for the situation of youth clubs and associations in North Africa, marginalised both socially and geographically: this centre is located in a peripheral area of Casablanca, isolated from the social and cultural life of the city, and surrounded by industrial sites.

On the relevance of this cultural institution to marginalised youth in a big metropolis such as Casablanca, Morocco, José Sánchez García writes: (97)

“The interest in the notion of youth agency may reflect two different approaches: the first considers youth as a potential danger to the social order, while the second considers young people as social agents who are potentially involved in social processes. of social and cultural innovation, and as producers and distributors who generate significant economic benefits. The youth construction of culture – that is to say the mode by which young people participate in the processes of cultural creation and diffusion – highlights the influence of the world of youth on society as a whole, and leads to the recognition of youth cultural practices as an expression of the creative, and not just imitative, capacity of these young people.”

Egypt

Young people represent half of the population in Egypt. They are especially eager to find a job. According to ILO estimates in 2022, the percentage of unemployment stands at 17,1. (98)

From Mohamed Morsi to Abdel Fatha Al-Sissi, nothing has changed in the daily life of Egyptians. Political instability has jeopardised the return of investors and the key tourism sector. Since 2011, all economic indicators have turned red, and Egyptians see no improvement, on the contrary Egypt is approaching bankruptcy. More than 26% of Egyptians live below the poverty line. 40% on less than $2 per day.

According to the World Bank estimates: (99)

“In 2019, before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, an estimated 1.5 percent of Egyptians lived on less than the international poverty line of US$2.15 (2017 PPP US$) per day and 17.6 percent of the population lived on less than US$3.65 per day, a poverty line used by the World Bank as a benchmark for lower middle-income countries, to which Egypt belongs. Official estimates for 2019 showed that 29.7 percent of the Egyptian population was poor. In 2015, about 27.8 percent of Egyptians were poor. Between 2015 and 2017, households’ per capita consumption growth was negative for most households reflecting the sharp rise in inflation following the 2016 currency depreciation. This contraction in consumption translated into an increase in poverty between 2015 and 2017. Trends between 2017 and 2019 show signs of improvement, with households’ consumption growing for most households.“

Critical in Cairo and the big cities, the situation is even more critical in the villages and is causing collateral damage. In Al-Our, 200 km south of Cairo, no road, no drinking water, no health service and above all no work.

Concerning The status of youth in Egypt after the Arab Spring and the COVID-19 pandemic, UNICEF writes: (100)

“Egypt is the most populous Arab nation and Africa’s third most populous country, with 101.5 million inhabitants in 2021. Optimising the potential of Egypt’s young demographic profile is a national priority: an estimated 51 per cent of residents are aged under 25 years, with just 5 per cent aged over 65 years. Given Egypt’s young demographic profile, one of its urgent national priorities is the fulfilment the rights of children and adolescents. Over the past few decades, the country’s service infrastructure has not been able to cope with its burgeoning population, compounded by a sequence of economic shocks, most recently the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic but also insufficient investments in sectors such as education, health and housing. Persistent poverty, regional inequalities, detrimental gender and social norms have also been intersecting challenges to achieving the potential of this demographic dividend. In 2017, 60 per cent of all children aged 0-17 years resided in rural areas. With Egypt’s service infrastructure concentrated in its urban areas, most children and adolescents are lagging behind due to inadequate access to essential services, especially in regions such as rural Upper Egypt, which has the highest rate of poverty and child deprivation. Further, the COVID-19 pandemic has interrupted a short-lived episode of economic recovery. While increasing poverty remains a major challenge, Egypt’s water scarcity issues further compound the situation.”

Youth employability and entrepreneurship have in the past decade become policy priorities in Egypt in a wide range of fields as a response to the challenges young people face in the contemporary labour market. The role of youth work in supporting young people in this area has been much debated. On one hand youth work can evidently help young people to develop a variety of competences and empower them to make a positive change in many areas of their lives, which inarguably also predicts a better position for them in the labour market. On the other hand, it is also argued that young people’s challenges in the world of work are rooted in structural and systemic factors, which should be addressed otherwise.

Egyptian Association for Comprehensive Development (EACD)

The history of the Egyptian Association for Comprehensive Development (EACD) begins 28 years ago in Egypt, but the cooperation between EACD and People Power Inclusion (PPI) (101) is more recent. After a first successful project in 2019, and while the effects of the Covid crisis on youth employment in Egypt are disastrous, EACD and PPI are once again joining forces to reduce the gap between supply and demand for work. The objective is clear: to qualify young people for the job market – whether as employees or entrepreneurs.

The Egyptian Association for Comprehensive Development (EACD) was established on December 25, 1995, with the aim of developing the capabilities of the most deprived individuals, particularly youth, women and children from rural and informal communities.

The EACD was thus formed and it focused on four main objectives:

- Develop policies and strategies that improve the skills of community members in various areas, such as health, education, environment and economy, focusing primarily on women, children and youth (Egyptians, refugees and migrants);

- Design and implement development programs aimed at improving living conditions in disadvantaged rural areas or those lacking infrastructure;

- Initiate mutual cooperation between civil society organizations and the public and private sectors through dialogues aimed at the sustainable development of society; and

- Build and extend the tools and methods of development activities of community development associations, in order to support the capacities of their institutional structure to ensure a sustainable development role.

EACD focuses on five main areas of action: economic development, health, education, women’s empowerment, including the fight against violence, and environmental preservation.

Over the past 28 years, EACD has served more than 20,000 direct beneficiaries per year. EACD prides itself on the fact that most of its employees are people living within the target communities, which contributes significantly to enhancing the impact of the services provided and reflects the scale of positive change achieved through the work of EACD.

The idea of the “Youth Employability and Entrepreneurship Booster” (YEEB) (102) project was born from the difficult economic situation caused by the Covid pandemic: many people have lost their jobs or part of them and consequently their income. Thousands of Egyptian entrepreneurs have had to cease their activity.

EACD therefore decided with PPI to develop an employment program – including self-employment – targeting young people in marginalised areas of Greater Cairo. The objective of this project is simple: to qualify young people for the job market, whether to help them find a job or to support them in the development of a small business.

The main impact of the YEEB project is reflected in the emphasis placed by the EACD on developing young people’s motivation, strengthening their confidence in themselves and in society, and emphasising their abilities to train and develop in various fields. YEEB selects groups of young people who have a real need for employment and works to develop their commitment so that they become attractive to the private sector – or to clients in the case of micro-entrepreneurs. The objective is to reduce the gap between real market demands and human resources.

EACD started with 4 training programs in El Marg and Maadi (Greater Cairo) and 93 beneficiaries actually participated, 35 of whom found employment which they keep until today! This project has its origins in a 2019 project called “Start for Tomorrow”, in which the EACD established partnerships between the private sector and trained young people, with the support of PPI (called at the time ‘’Positive Planet International’’ ). (103)

In 2023, PPI (People Power Inclusion) and EACD formed a new partnership around the idea of YEEB, following on from “Start for Tomorrow” and even expanding the scope to include entrepreneurship alongside employment.

Jordan

Half of Jordan’s population is made up of Palestinians who fled their land in 1948 after the creation of Israel and in 1967 during the Six-Day War. With 11,38 million inhabitants according to Worldometer in 2024, (104) Jordan is the second country, after Lebanon, with the highest number of refugees per resident: it hosts 655,000 Syrians, 67,000 Iraqis, 15,000 Yemenis, 6,000 Sudanese and 2,500 from other states. (105)

In Jordan, social unease remains very present among young people. The grim economic situation is a formidable social hassle. Corruption is everywhere, it is being fought by the authorities on the surface, however, the big fishes always get away with it and this fact reduces the legitimacy of the establishment in the eyes of the masses. Despite easy access to education, there are few opportunities for young people on the job market in Jordan, particularly for young women. transition periods from school to working life can be extremely long. While some young people manage to quickly find a job after leaving school, those for whom this is not the case take almost three years to find a stable or satisfying employment. (106)

On the issue of unemployment in Jordan, Jalal Al Husseini, and Raad Al Tal write: (107)

“Jordanian authorities identify unemployment as one of the country’s main challenges. Long stabilized at an already high level of 10% to 14% until 2014, the unemployment rate amongst Jordanians has since then increased dramatically, reaching 19.1% in 2019 and, following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, a record 24.1% in 2021. The highest unemployment rates were recorded in the youth category aged 15 +- 24, which represents one-fifth of the population (19.9%) and 28.5% of the Jordanian labor force4. In the second quarter of 2022, 46.1% of them were reported as unemployed.’’

According to the World Bank, the share of young people who are neither in employment, nor in studies, nor in training, men (% of the male population aged 15-24), is around 28,3 % in 2021. (108) As to what concerns the unemployment of the youth (% of active population aged 15 to 24) it is around 43.7% in 2021. (109) As for unemployment among young men in the male working population aged 15 to 24 in Jordan, a modelled estimate from the International Labor Organization (ILO) puts it at 36.6%. (110)

The number of young people aged between 15 and 24 in Jordan was estimated at 2.246 million at the end of 2021, out of a total population of 11.302 million, according to figures from the Jordanian Department of Statistics. (111)

In Jordan, only a few graduates find employment in their field after their studies. The unemployment rate stands at 19%, constantly increasing in recent years. Among young people, and more than half of the Jordanian population is under 25 years old, it even reaches 40%. Among those who work, many are self-employed or employed in the informal sector. They are not registered with unemployment insurance.

There are not enough jobs for all new graduates and even fewer for women. Unemployment is high for essentially structural reasons. On the one hand, university graduates do not have the qualifications required by the job market, particularly in IT or languages. On the other hand, the strong protection of workers against layoffs does not encourage the creation of new jobs. The latter are also located in Amman. For people living outside the capital, working in the city is not worth it: salaries are too low and transport costs too high. (112)

Explosion of unemployment, lack of prospects and increase in the cost of living are harming the population. Amman is the most expensive capital in the Arab world. It is therefore not surprising that in the summer of 2018 thousands of people took to the streets to demonstrate against a bill to increase taxes. Prime Minister Hani Mulki was forced to resign. The king then appointed Omar Razzaz as head of government.

Changing prime ministers to quell unrest is the strategy used over the years by the Jordanian monarchy: a political concession without deep transformation. The demonstrators have, in a conscious and reasoned manner, demanded concrete reforms. While denouncing corruption, they demanded economic reforms. A clever tactic. The protesters initially did not question the system, fearing the disastrous consequences suffered by other countries. The monarchy still enjoys the trust of many Jordanians, unlike the government and Parliament. (113)

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the already precarious economic situation has worsened. For the economy, the effects of the coronavirus are worse than the shock that followed the financial crisis and the Arab Spring. At the time, Jordan’s economic foundations were strong. Conditions today are much worse. (114)

Fostering Youth’s Role in Community Development

Hashemite University signed a partnership agreement with the King Hussein Foundation to implement the European Union (EU)-funded project “Fostering the Role of Youth in Community Development.” The agreement was signed on behalf of the Hashemite University by the President of the University, H.E. Professor Fawwaz Al-Abed Al-Haq, and on behalf of the King Hussein Foundation, by the Executive Director H.E. Hana Shahin, and in the presence of H.E. the Ambassador of the European Union to the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, Mr. Pierre-Christophe Chatzisavas.

During the signing ceremony, Professor Fawwaz Al-Abed Al-Haq said that the Hashemite University is dedicated to providing students with the skills, knowledge and opportunities they need to succeed in their careers and bring a positive contribution to their communities. Professor Al-Abed Al-Haq said that this project aligns with the university mission and: (115)

“…we are excited to embark on this journey to create a positive impact on our students and the community of Zarqa and Mafraq governorates. This European Union-funded project will have several key impacts on strengthening students’ leadership and entrepreneurial skills, promoting civic engagement and encouraging innovation and creativity to develop community initiatives. Through the implementation of these projects, the university will be able to create a lasting impact on the lives of young people in Jordan and contribute to the improvement of their communities.”

Ms. Hana Shahin said in her remarks that this program demonstrates the sustainable development programs of the King Hussein Foundation in the areas of poverty eradication, women and youth empowerment, microfinance, health and arts for social development and intercultural exchanges. This project will strengthen students’ capacity to implement community initiatives that serve the communities surrounding Hashemite University. By combining their assets with supportive resources and opportunities to instil a sense of responsibility and interact with others, young people can become change makers, innovators, communicators and leaders in their communities.

For his part, Ambassador Pierre-Christophe Chatzisavas said: (116)

“The EU is pleased to partner with the Hashemite University and the King Hussein Foundation to support youth initiatives for the benefit of the communities in the governorates of Zarqa and from Mafraq. With key skills like entrepreneurship and innovation, young people gain confidence and the ability to take initiative and create positive change in their communities. We hope that this program will indirectly reach 10,000 beneficiaries, including women and people with disabilities, to have a significant impact. And beyond this immediate dividend, we want to be on Jordan’s side as it invests in the next generation.”

The Director of the Community Development Institute of the King Hussein Foundation, Mr. Muhammad Al-Zoubi, also presented the project in which he explained that the project would strengthen the role of youth in local community development in order to meet the needs of the community surrounding the Hashemite University of Zarqa and the governorates of Mafraq. The project will also enrich the role of the Hashemite University as a hub promoting the civic engagement of young people; and strengthens their capacities to implement community initiatives that serve the communities surrounding Hashemite University.

It should be noted that this project will be implemented over a period of 30 months. It will include five phases and 12 activities, and will be implemented through a specialized project team from the Hashemite University Center for Studies, Consultation and Community Services and the University’s Career Center in partnership with a team from the Community Development Institute of the King Hussein Foundation.

Young Cities

Nature of the activity

On May 11, 2022 Young Cities held its first Showcase event in Amman, Jordan, with the support of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and its local partner, the WANA Institute. Presentation events are the cornerstone of the Young Cities programme. They establish young people as essential actors in tackling key community challenges, while providing them with opportunities to connect with local, national and international leaders, so that all groups can advance their mutual interests. (117)

The exhibition in Jordan allowed 15 young people who participated in the “Young Cities” program to network and present the impact of their initiatives – regarding COVID-19 misinformation, cyberbullying and the inclusion of people with disabilities – to 65 multi-sectoral stakeholders. The teams combined formal presentations with interactive booths to share the innovative approaches they have taken, including using puppet shows and conducting art therapy training, to address the challenges faced by team members of their community.

In addition to amplifying their peacebuilding work, the event gave youth groups the opportunity to improve the sustainability of their projects by encouraging potential partnerships that can strengthen their impact. They were able to contact the mayors of Karak, Irbid and Zarqa, as well as members of the local prevention networks (LPN) in each city. Other participants with whom the young people were able to network included representatives from the Norwegian Embassy and the Ministry of Local Government, civil society leaders from youth centres and NGOs, academics from the University of Jordan and the Royal Scientific Society, as well as early-stage investors from the private sector.

The Mayor of Zarqa and members of the WANA Institute noted that the “Young Cities Showcase” event was an important reminder that young Jordanians are essential to current and future efforts towards peace and cohesion social.

Goals achieved

Below are the key takeaways from the Jordan Showcase:

1. 80 actors from the youth and peacebuilding sectors, academia, private sector, civil society and municipal, national and international institutions participated in the Young Cities exhibition. The event provided a crucial opportunity to strengthen cross-sector networks and spark constructive dialogue on how best to address community challenges in a spirit of collaboration. The involvement of young people in these discussions and the possibility of giving them a platform are essential to the success of these events. The three youth teams were able to share their perspectives on what they see as the biggest threats to Jordan’s social fabric and how they think civil society and government responses could be improved. By connecting young people with decision-makers and local organizations, the impact of the event is more lasting as new networks are created and participants can concretely discuss the potential for shared solutions to common challenges.

2. By interacting with a diverse set of stakeholders, the youth groups were able to form new relationships important for their future careers, including with representatives of the Norwegian attaché. Representatives from the Department of Local Government also encouraged teams to contact the Department of Home Affairs, which regularly funds new local organizations and initiatives. Likewise, youth-focused civil society organizations offered support and proposed future collaboration, sharing upcoming training opportunities that may be of interest to youth groups.

3. The exhibition blended formal presentations and panel discussions with informal networking opportunities and interactive exhibits led by young participants about their initiatives. The use of different formats and interaction platforms made it possible to fuel the dialogue in a different and meaningful way. While the formal presentations and roundtable discussions allowed officials to speak directly to their communities and hear their concerns, the informal exhibitions allowed for in-depth dialogue between young people and the decision-makers who represent them. The connections made during these interactions not only became starting points for new relationships, but also encouraged a less top-down approach to engagement between young people and the city and between the local and national level.

Conclusion: what future for the excluded of the Arab World?

For half a century, population has been seen as a problem by Arab governments. Until the 1980s, the problem came from too high a birth rate and the solution lay in birth control. One by one, all Arab governments therefore adopted family planning programs and the number of births stabilized, and in some places decreased. The largest generations are those born in the 1980s and 1990s. They are at the age at which they enter working life. The demographic problem has shifted from newborns to young adults and 20–35-year-olds, perceived as the sensitive age group par excellence. Their numbers have grown faster than the resources they have access to, from employment that provides income and status, to freedoms and political participation. (118)

Arab job markets have become particularly difficult for young adults. Not only are their generations the largest but, for the first time, young men are in competition with young women, whom a spectacular delay in the age at marriage and motherhood now frees them for the exercise of a professional activity. Furthermore, thanks to the considerable efforts made by families and states to develop education, young people of both sexes have received more school and university education than all previous generations. While populations are only growing at a rate of between 1% and 2% per year, the working age population is growing annually by 3%, job demand by 4-5% and the mass of human capital, which presents itself on the labour market, by 6-8%. (119)