Urgent Need To Engage Pacific Islander Communities In Hawaii To Contain COVID-19 – Analysis

Pacific Islander communities in Hawai‘i face unique socio-economic, historical, and cultural challenges in coping with COVID-19. Many are ineligible for Medicaid and either work in lower-paying hourly jobs or are unemployed.

By David Derauf, F. DeWolfe Miller and Tim Brown*

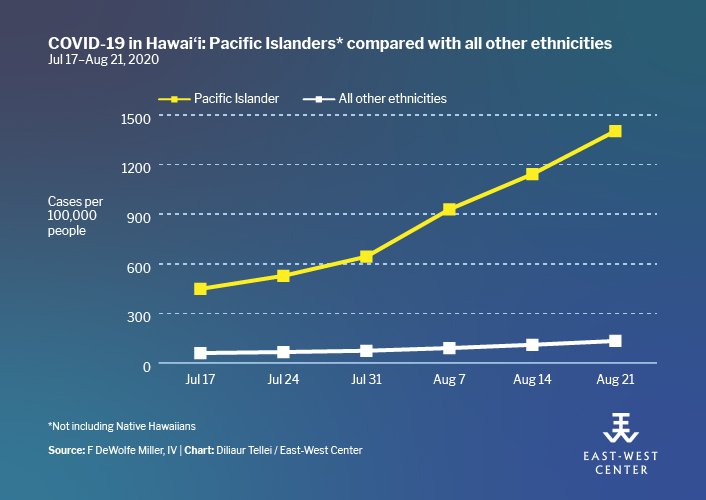

The global COVID-19 pandemic, like every public health crisis, exposes societal fissures and failings. Almost inevitably, there are those who are left behind, where responses come too late. Here in Hawaiʻi, the COVID-19 epidemic has grown explosively since the end of July with an average of 220 cases a day reported in the week ending 21 August. But while the epidemic affects everyone, Hawai‘i’s Pacific Islander communities have been hit hardest of all.

Pacific Islanders other than Native Hawaiians have ten times the infection rate of all other ethnic groups in Hawai‘i. Furthermore, the rate of COVID-19 infection in these communities is growing much more rapidly than in the rest of the population.

Socio-economic challenges

Pacific Islander communities in Hawai‘i face unique socio-economic, historical, and cultural challenges in coping with COVID-19. Many are ineligible for Medicaid and either work in lower-paying hourly jobs or are unemployed. This forces them to either go without health care or rely on overburdened community clinics. As the COVID-19 epidemic spreads widely in the community, these community clinics are increasingly stretched thin, especially as many of their own staff are exposed and quarantined.

Pacific Islander households also tend to be multi-generational in nature, leading to crowded living quarters in Hawai‘i’s overpriced housing market. This makes it difficult for people to isolate, inviting rapid COVID-19 transmission.

What’s more, the pressures of American assimilation already challenge cultural patterns of connectedness among Pacific Islanders, and the additional separation that COVID-19 prevention requires can trigger existing historical traumas related to colonization and discrimination. This makes communications with the communities even more complex. If undertaken by those with little cultural and linguistic experience with these communities, it can contribute to further virus spread.

Meanwhile, the state’s response to COVID-19 has largely overlooked these communities, only recently starting to offer COVID services geared specifically for them. Testing has been limited and slow, urgently needed rapid contact tracing has been slow and plodding, and opportunities for quarantine outside of crowded quarters have been impeded by limited hotel inventory and poor communications. Media reports and educational materials are primarily available in English, and the limited translated materials available are often inaccessible to many community members due to literacy and a failure to understand the venues where Pacific Islander sub-communities naturally communicate.

Lessons from HIV

There are important lessons to be learned about managing COVID-19 from another global pandemic: HIV. These lessons are critically important to an effective response for neglected Pacific Islander communities in Hawaiʻi:

- First, learn from members of affected communities who know their own situation best. Outsiders often misread or fail to fully comprehend the needs, concerns, and perceptions of risk in different Pacific Island cultures. They usually lack the cultural experience or language skills needed to work within the communities without generating mistrust or triggering historical and cultural trauma. A response can only be effective if Pacific Islanders and the organizations they trust are active partners, not passive recipients.

- Second, Pacific Islander communities must be leaders and equal partners in the response. Pandemic responses that focus only on the health sector are inadequate to address the multiple factors driving transmission in these communities. Instead, effective responses must be multi-sectoral, engaging community leaders, social service agencies, and social science researchers from within the community to develop effective communications and service strategies. Only then will they fully reflect and address the needs of the community.

- Third, an effective response must address the social and economic factors driving transmission. For some in Pacific Islander communities, crowded living situations, low income, disparate access to health care, language barriers, and a host of other issues create a more fertile ground for COVID spread. These issues keep the communities from taking the steps necessary to protect themselves. Unless these issues are addressed, COVID will continue to spread unimpeded.

Critical needs unmet

The State of Hawaiʻi’s COVID-19 response to date has been primarily a health sector response, directed and largely run by the Department of Health (DOH). As such, given DOH staffing limitations and lack of familiarity with Pacific Islander communities, it has failed to appropriately address their needs. The result has been volatile COVID-19 growth. Staff and patients at Kōkua Kalihi Valley (KKV), a community health center working closely with Pacific Islander communities, have highlighted several critical needs that have not been met. These include:

- More agile and language-appropriate communications developed in partnership with leaders of affected communities and delivered consistently through appropriate channels, such as social media and church and youth networks. Six months into the pandemic and KKV is still struggling to locate and/or translate appropriate messaging and adapt it to the natural communications networks of Pacific Islander communities.

- Effective, transparent, and sustained engagement of Pacific Islander leaders as full partners, including consulates, churches, traditional leaders, nonprofits, and other groups representing Pacific Islanders. While some good work has been done in this area, so far it has been too little and too late to disastrous effect.

- Clear public communications policies for avoiding stigma and bias against marginalized communities. Despite repeated experiences showing that stigma and discrimination work against effective prevention, public leaders and media frequently single out Pacific Islanders. Such public shaming is a significant barrier to COVID education and response, particularly among communities already struggling against systemic racism.

- Robust contact tracing that accounts for the unique social, cultural, and historical barriers in each community. The state’s failure to establish adequate contact tracing has been felt most dramatically in Pacific Islander communities, where exposed and positive individuals in crowded living quarters are mostly not provided timely—or even any—case investigation or contact tracing, nor offered COVID tests for exposed family members.

- More effective assistance with quarantine and isolation in economically-strapped, high-density households. There is a critical need for more culturally effective messaging, access to unused hotel rooms for quarantine support, and humane systems for supporting families facing either home quarantine or temporary relocation.

- Comprehensive and timely family support to address such issues as food insecurity, unemployment, a lack of personal protective equipment and hygiene supplies, COVID misinformation, and other critical barriers that have been causing Pacific Islander families to drop through the cracks in alarming numbers. We cannot responsibly expect families to quarantine or isolate effectively without these supports.

How to engage affected communities for an effective response

A good start would be for the state Department of Health to adopt recent recommendations from the Hawaiʻi and Pacific Islander COVID19 Response, Recovery, and Resilience Team. These can be found at: https://www.slideshare.net/civilbeat/nhpi-covid19-statement.

The following recommendations to the State draw upon the response team’s work and are intended to be complementary:

- Foster a culture of shared kuleana and innovation. The State’s pandemic response has been obstructed by blame shifting, a lack of transparency, and a dearth of community experience. Individuals with a proven track record of community leadership, consensus building, and logistics, rather than just content expertise, should lead working groups. Whether or not these individuals are public employees, a unified state and county leadership should fully mandate and support them. Pacific Islander leadership from subcommunities should also be fully engaged, resourced effectively, and informed on a regular basis, especially when these subcommunities are experiencing disproportionate spread. The state and city should each appoint high-level community contacts charged with cutting through bureaucratic barriers and supporting innovation at the community level.

- Provide resources to communications teams of Pacific Islanders and experts who can assist communities with emerging messaging needs, including inventorying, adapting, disseminating, and advising on language-appropriate COVID resources; standing up language-specific hotlines and single points of contact; and working closely with community leaders to identify the unique considerations for effective COVID education and response specific to each Pacific Islander community. Such considerations include, for example, social media misinformation, alternative strategies for honoring essential cultural practices such as funerals, de-stigmatization, and education in how extended family members can safely support COVID-positive relatives.

- Better support for families during quarantine and isolation, including providing food, protective gear, hygiene supplies, economic and social assistance, and—when warranted—free hotel rooms or other suitable housing relocations. Each family must be contacted within 24 hours of a positive test by a trusted language-appropriate navigator for the duration of isolation. This requires allocating a significant increase in resources to nonprofits, community groups, and even health insurers with available community-support staff, as well as rapidly recruiting navigators from Pacific Islander communities. It is also critical to establish easy-to-understand online training, up-to-date resource guides, and appropriate standards for navigators. Data-sharing agreements should be quickly executed among state agencies and nonprofits to facilitate communications and coordination.

- Rapidly expand case investigation and contact tracing in partnership with nonprofits and community groups. Hawai‘i needs upwards of 400 contact tracers statewide, including individuals fluent in Pacific Island languages. Online training resources from the University of Hawai‘i and national sources could be used to prepare large cohorts of contact tracers from affected communities. Whenever possible, contact tracing should be integrated into the overall family support system. Training for contact tracers should be geared toward community health workers, with no B.A. degree requirements, and should be completed within two weeks. In addition, training should foster empathy and allow trainees to interpret complex concepts into the cultural contexts of their own communities. Training resources can be quickly and appropriately adapted that will prepare contact tracers to start immediately under appropriate supervision, and their skills and abilities will grow with time to meet the needs of Hawaiʻi’s diverse communities.

Positive action required now

The reasons why Pacific Islander communities have so far borne the brunt of the pandemic in Hawai‘i should be obvious to all: extremely overcrowded housing, which makes household COVID transmission a certainty and isolation nearly impossible; low pay for front-line workers throughout our economy, making hunger and possible eviction a likely outcome of sheltering in place; and low English literacy combined with ineffective government messaging in key languages. Underlying these conditions is Hawaiʻi’s systemic racism against Pacific Islanders and the long tail of historical and colonial trauma that plays a determining role in how these communities respond to State strategies for COVID-19 containment and mitigation.

Messaging around solutions for the epidemic needs to broaden beyond individual behaviors to include discussion of systemic responses to broader cultural and social support needs. An individual’s failure to follow quarantine and isolation orders, for example, often results from their need to provide for their family. It can also result from an individual’s mistrust accumulated over years of systemic disenfranchisement of his or her community, in which case, honoring and resourcing the agency of Pacific Islander leadership is especially critical.

The “fierce urgency of now” created by the surging COVID-19 epidemic among Pacific Islanders in Hawai‘i calls for urgent, positive action. The state response must broaden immediately to engage Pacific Island communities as equal partners, provide for truly collective and just approaches to health care and support needs, and channel resources to community organizations and stakeholder groups in a way that allows them to take leadership in COVID prevention and care.

Only by enabling Pacific Island communities to proactively take on the COVID-19 epidemic in their midst will state leaders achieve the outcomes we all seek—stopping the spread of COVID and its increasingly catastrophic health, economic, and community impacts.

*Dr. David Derauf is the Executive Officer and a family doctor at Kōkua Kalihi Valley, a community health center working closely with Hawaiʻi’s Pacific Islander communities. Dr. F. DeWolfe Miller is an Emeritus Professor at the University of Hawaiʻi specializing in infectious disease epidemiology. Dr. Tim Brown is a Senior Fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu, specializing in HIV modeling and the design of effective epidemic responses.