Navigating Realism And Global Challenges: An Analysis Of G-20 Summit Declaration – Analysis

By Mukesh Sahay and Lucky Sharma

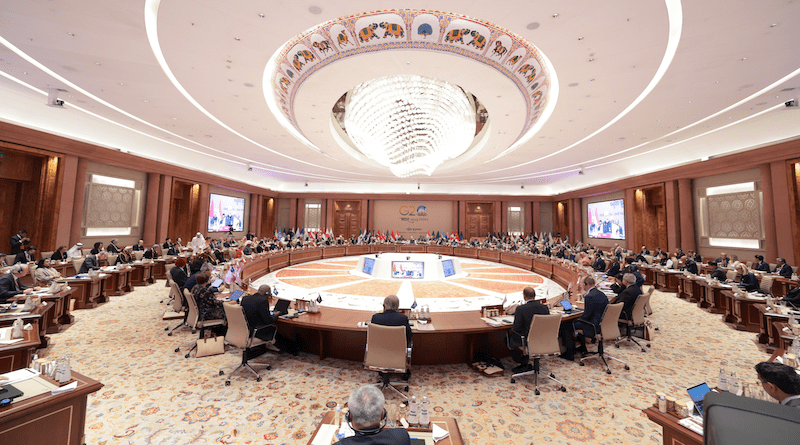

The eighteenth G-20 Heads of State and Government Summit in India on 9-10 September 2023 marks a new epoch in the age of multilateralism. In light of the contemporary global crises due to the Ukraine war, the global climate disasters and the international food crisis, it is imperative to see its impact shortly.

A wide range of consensus arrived from innovation to inclusiveness, peace to prosperity, and stability to sustainability in the summit. The G20 meeting in 2023 centres on the theme- One Earth, One Family, One Future under the Indian Presidency. The summit was held in the light of six G20 priorities-Green Development, Inclusive Growth, progress on the SDGs, Technological Transformation, Multilateral Institutions for the 21st century, and Women-led Development. The subject upholds the importance of people, animals, plants, and microorganisms with their interdependence on Earth and the entire cosmos. The real success of the Delhi leaders’ declaration depends on the future trajectory of the global geo-politics. The twenty-first century is on the brink of several manufactured disasters in the form of climate change, nuclear wars, supply chain disruptions and the global food crisis. Now, it is essential part of each multilateral agency to address all such challenges, to save the globe.

Assessing the G-20 Summit: Past, Present, and Future:

Before judging the relevance of the 18th summit, we need to examine the genesis and the evolution of the G-20 and draw some fine line metrics to evaluate the impact of the present summit. The post-second world war scenario of the world created a new world order, which called for the multilateral platforms of the globe to meet the contemporary global challenges.

The Delhi leaders’ declaration reveals, ‘The global order has undergone dramatic changes since the Second World War due to economic growth and prosperity, decolonization, demographic dividends, technological achievements, the emergence of new economic powers and deeper international cooperation. The United Nations must be responsive to the entire membership, faithful to its founding purposes and principles of its Charter and adapted to carrying out its mandate. In this context, we recall the Declaration on the Commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the United Nations (UNGA 75/1) which reaffirmed that our challenges are interconnected and can only be addressed through reinvigorated multilateralism, reforms and international cooperation. The need for revitalized multilateralism to adequately address contemporary global challenges of the 21st Century, and to make global governance more representative, effective, transparent and accountable, has been voiced at multiple fora. In this context, a more inclusive and reinvigorated multilateralism and reform aimed at implementing the 2030 agenda is essential.’ (G20 New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration, 2023)

The above declaration calls for the importance of agencies in the age of realism. However, as far as the global geopolitic statics is concerned, it is generally driven and outwitted by the principles of realism. It is great to see the consensus on the leaders’ declaration of the summit, but at the same time, no specific agenda came to solve the Ukraine crisis. In addition, we do not find the specific commitments of the developed nations toward the challenges of catastrophic global warming due to rapid climate change. Despite a UN report from a day earlier describing the drawdown as ‘indispensable’ to achieving net-zero emissions, leaders were unable to agree on the phase-out of fossil fuels. However, for the first time, the G20 endorsed a goal of tripling the amount of renewable energy produced worldwide and made mention of the requirement that emissions must peak before 2025.

Geopolitical Shifts and Economic Corridors: G20 Summit 2023 Analysis:

The US, India, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, France, Germany, Italy and the European Union signed a memorandum of understanding on the India – Middle East – Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), seen as a possible alternative to the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative. The planned corridor would link India, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Jordan, Israel and the toe to boost trade and economic growth.

In addition to this, the EU and the US decided to join forces to promote the Trans-African Corridor connecting southern Democratic Republic of Congo and north-western Zambia to regional and global trade markets via the Port of Lobito in Angola. (Parliament, 2023) The absence of China’s President Xi Jinping, leader of the world’s second-largest second-largestcted significant media attention and several analysts concluded that China is disillusioned with the G20 as it is too dominated by US influence and that the country prefers to pursue a new global system of governance. To some scholars, the absence of President Xi at a time when India is emerging as a counterweight to China- makes him the biggest loser of the summit.

The leaders also called for the implementation of initiatives like the Black Sea grain initiative to ensure e uninterrupted supply of grain. Some scholars believe that India successfully represented the Global South during its G20 presidency, particularly by selecting issues that affected poor nations and by seeking to make the AU a permanent member of the G20.

Today, the G20 is the world’s most powerful economic body. Its members combine over 80% of world GDP, 75% of global trade and 60% of the population. Its core agenda is the world economy and global economic leadership. Post 2008, it is also focused on creating rules and institutions that will prevent another financial crisis. Now, with the existing multilateral order like the United Nations (UN) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) weakening and its authority contested, other pressing global issues are also discussed at the G20. (Kripalani, 2021)

Transformations and Turmoil: Journey from Crisis Response to Global Economic Governance:

The evolution of G-20 from its origin underwent a lot of topsy-turvy positioning as Jonathan Luckhurst opines, ‘In the late 1990s, the Asian financial crisis damaged several developing economies, which many western officials blamed on poor governance standards, “crony capitalism,” and institutional flaws in those countries. The Canadian and WE governments, with other allies, following a key meeting in 1999 between US Treasury Secretary–designate Larry Summers and Canadian Finance Minister Paul Martin, created the G20 Finance forum as an international response. The focus of the new forum would be to share the best economic policy practices from its wealthy members with strategically significant developing-state members. Policy learning and adaptation were intended to be principally one way, based on the assumption of superior policy norms in the wealthy members. A decade later, somewhat ironically, the wealthy states suffered most from an equally dramatic financial crisis, centred on the USA and Europe. This crisis, due to its global effects, commonly became known as the ‘global financial crisis,’ abbreviated to GFC. Not all regions and countries were equally affected, but the near-global impact of the 2008 financial crisis justifies the name.

The financial crisis became international in late 2008, but began in the USA when the sub-prime mortgage market collapsed in 2007 and a liquidity crisis ensued in the US banking sector. The increasingly fragile circumstances of the US financial sector in 2007–2008 only led to an International crisis with the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers Investment Bank on September 15, 2008. Stock markets crashed in many countries, and several financial institutions in Europe, Asia, and elsewhere experienced severe liquidity problems. Policymakers around the world suddenly found themselves in profoundly challenging and uncertain economic circumstances.

The US-led international economy and the liberal economic beliefs upon which the international economy was founded were undermined and brought into question. The most popular models of financial risk management suddenly lost credibility, while economic growth predictions were radically lowered in countries substantially exposed to the international economy, which meant the majority.’ (Luckhurst, 2016, pp. 1-2)

From Crisis to Catalyst: G20’s Role in Reshaping Global Economic Governance:

After the global financial crisis-, it was a herculean task to put the global economy back on track. The G20 appeared as a catalyst for the reorganization of global economic governance. The outright ignorance of the leading developing nations like Russia, China, India and South Africa resulted in the lob-sided disaster of the elite economies. Organizations like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), New Development Bank (NDB) and BRICS had the potential to abandon the Bretton Woods institutions due to lack of inclusivity. Given the situation, G20 was established as the forum of the equals, where no single nation dominates the decision of the governance and all the key issues of global governance get the due respect.

Parthasarathi Shome observe the balance of global economic power in terms of GDP and international trade in the early 2000s had become more dispersed, with a need for recognition of this new balance. The formal Bretton Woods system, its mandate, and mode of operation had become somewhat wanting in this new world order of the 2000s. Its inability to recognize or expand the role of emerging economies meant that they could not cope with changing times. Even the dominant triad of the G7 – United States, Japan and Europe – could not adequately counter interconnected challenges including macroeconomic imbalances, development imbalances or the provision of global public goods, in particular, energy, commodities and environmental sustainability.

Emerging economies, with superior growth performance in recent years, increasingly began calling for a place at the negotiating table. The Asian economic crisis of 1997–98 and the global crisis of 2008–09 finally resulted in modifications in the way global economic governance was organized. The formal governance system – the UN Security Council, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank – were not adequately suited for resolving emerging crises as they primarily reflected the preference of the old world o and, hence were increasingly unable to enjoy the confidence of the emerging economic powers. The need of the hour was a truly global network that adequately reflected the new political and economic Multi-polarity, and to synthesize a more representative balance of power with a transparent framework for global economic governance. Thus, the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors’ Network in 1999 after the Asian crisis and the G20 at the Leaders’ level in 2008 with the onset of the global crisis. The emergence of the G20 recognizes the fact that, in an increasingly integrated world economy, problems become, more often than not, global. This, in turn, demands global solutions involving all stakeholders, including the newly emerging market economies. (Shome, 2014, pp. 3-4)

The economic agendas of G20 are devised keeping in view the domestic economy; international political economy; global economy and growth prospects; economic trends and shocks in the G20 countries; and consideration of bringing to the table agenda items that cater to counterparts’ issues and secure buy-in from other G20 peers. As Saon Ray et al. opine, ‘The four-core agenda discussed several times includes the global economy, fiscal and monetary policies; international financial institutions; financial sector reform and regulation; and international taxation. Others that have been discussed less include infrastructure investment and spending; exchange flexibility; climate change; structural reforms; financial inclusion; reducing imbalances; and global financial safety nets. (Saon Ray, 2023, p. 85)

Behind the Scenes: G20 Agenda Formation and Global Engagement:

The process of agenda setting is also quite interesting. G20 personal representatives known as Sherpa led the preparation for the summit. It was observed in one of the summits, the Sherpas of the host country held meetings with all the other Sherpas to understand the expectations of each country from the host country’s presidency, which should fall in line with the conglomeration of international and domestic priorities.

The finance ministers, their deputies, central bankers, and Sherpas are a recurring feature of each summit and they maintain contact with each other during the year to discuss agenda items for the summits. This helps in fostering international coordination, along with producing a multifaceted agenda that accommodates a combination of current as well as past experiences of the world economy in one place. Sherpas and the Finance Ministers of the presidency country bring together working groups and task forces who carry out the technical work in the policy areas to be covered … In addition to these, each presidency is further assisted by engagement groups who advise and inform G20s on specific area decisions. There are five recognised engagement groups academicians, business leaders, civil society, organized labour, think tanks, and young leaders participating in organizing the summit. In identifying priority areas and policy areas, the G20 is supported by international organizations. (Saon Ray, 2023, p. 86)

In 2015, under the Turkish Presidency of the G20, for the first time, an Indian think tank, Gateway House, initiated and hosted a T20 meeting in India. It was in collaboration with TEPAV, the Turkish think tank assigned as the lead T20 Sherpa, by Ankara. India’s Central Bank governor, Dr. Raghuram Rajan, delivered the inaugural address – spelling out clearly what India’s goal and journey for engagement with the global economy and its governance, should be. He, who holds the pen, writes the rules, he said, and that should be India’s goal, to move from being a passive global rule-taker, to being confident global rule-maker.. More specifically, these relate to terrorism financing, money laundering and transparency in financial flows worldwide; the transparent cross-border flow of payments, remittances, aid and investments; the high cost of remittances; identification of beneficial ownership in multi-country financial transactions to protect against money laundering, terrorist financing and tax evasion.

The broader global issues include reform of the Bretton Woods institutions, reconfiguration of global financial regulations, design of a new framework for the digital economy as also trade in services, establishing better cross-border standards for transparency in financial and participation in the new global commons – space, oceans, cyber. (Kripalani, 2021, pp. 27-28) It cannot be denied that the Indian Presidency of G20 achieved the desired consensus but its real success would depend on the on-time deliveries and implementations of the upcoming global challenges.

References:

G. o. India (2023). G20 New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration. G20 New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration (p. 22). New Delhi Government of India.

Kripalani, M. (2021). India in the G20: Rule-Taker to Rule-maker. New York: Routledge India.

Luckhurst, J. (2016). G20 Since the Global Crisis. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US .

Parliament, E. (2023, September 14.09.2023). Thin Tank. Retrieved September 12.53 am, 2023, from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_ATA(2023)751474

Saon Ray, S. J. (2023). Global Cooperation and G20- Role of Finance Track. Singapore: Springer.

Shome, P. (2014). The G20 Macroeconomic Agenda_ India and the Emerging Economies. Delhi: Cambridge University Press.