Islamic State: Patterns Of Mobilization In India – Analysis

By Dr. Bibhu Prasad Routray and Mantraya

Sometime in the first quarter of 2015, an unnamed 20-year old class 12 pass out from Azamgarh, Uttar Pradesh travelled to Syria through Turkey to join the Islamic State. In September 2015, he called his parents from Raqqa and said he wanted to return home. He was reportedly frustrated with his time spent with Islamic State fighters. He also feared for his life. In November 2014, Areeb Majeed, one of the four youths from Kalyan, Maharashtra who had travelled to Iraq/ Syria to join the Islamic State in August 2014 returned home. Although some earlier reports detailed his frustration after being tasked by the Islamic State to carry out menial jobs like toilet cleaning, recent reports quoting the charge sheet prepared by the investigative agencies indicate that he had grown homesick and returned after his family pressured him to come back even at the risk of getting arrested. Apart from these two instances of rather swift disillusionment with the grand design of the Islamic State, most of the journeys undertaken by Indians to Iraq and Syria belong to the narrative of unrepentant adventurism and religious extremism.

The Indian government initially asserted that no Indian Muslim would ever join a foreign terrorist organisation. However, it now accepts that about 23 Indian youths have joined the Islamic State so far, out of which six have died, one has returned and the rest are possibly still with the outfit. It also says that 30 people have been stopped from travelling to Iraq and Syria. In addition, nearly 150 youths in the country, mostly from South Indian states, are under the surveillance of security agencies for their alleged leanings towards the Islamic State. Given the pull impact the outfit has over several countries in South and Southeast Asia this could be a highly conservative estimate. Private estimates of the number of Indians with the Islamic State by the same intelligence agencies who feed the government are far higher.

Notwithstanding the debate over the actual numbers, the article argues that it is possible to draw patterns from incidents in which Indians have either joined or attempted to join the Islamic State or have worked on behalf of the outfit within India. This exercise excludes the Indian nationals based in foreign countries or people of Indian origin who travelled to Iraq and Syria. The patterns drawn conform to the overall objective of the Islamic State to attract a wide range of people to either spend their lives in the Caliphate, fight on behalf of the outfit, and indulge in propaganda activities at the behest of the outfit as unpaid volunteers and recruiters. This further confirms the fact that far from being outdone by official denials, domestic factors that inhibit Indian Muslim youth from joining the outfit and the anti-Islamic State decrees issued by the Muslim organisations, some Muslim youths in the country have felt the need to join the Islamic State’s war efforts.

Seven specific patterns can be inferred from such journeys that include both physical as well as ideological relocations. These patterns help in understanding whether and in what form the Islamic State may be able to reinforce itself within India in the coming months and identifying potential areas for government intervention to prevent such journeys from being undertaken.

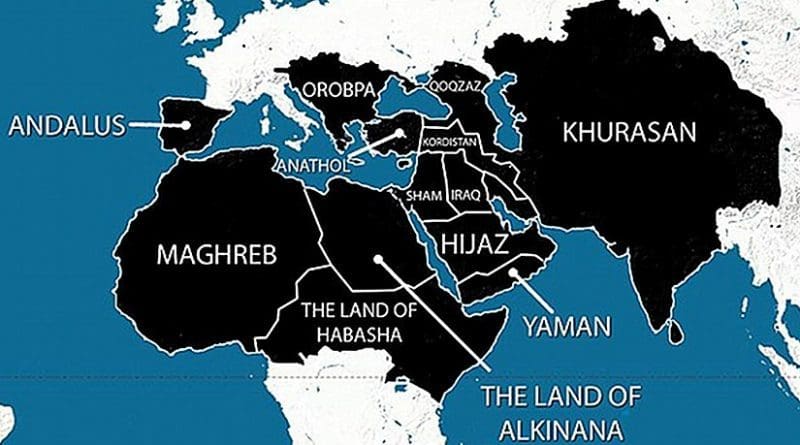

Firstly, timing of the recruitment, journeys and attempted journeys of majority of the Indians to become a part of the narrative of the Islamic State can be linked to the outfit’s Declaration of the Caliphate in June 2014. Travel of four youths from Kalyan, Maharashtra to Iraq to join the Islamic State is probably the most known episode in the short history of outfit’s designs on South Asia. That took place within two months after the IS caliphate declaration. Similar is the case of two college students from Kerala who went missing from their homes in July 2014 and landed in Syria to join the Islamic State. The declaration also marked the beginning of the waving of the Islamic State’s flags in Kashmir. Subsequent months saw a further rise in mobilisation efforts that resulted in further recruitment.

Firstly, timing of the recruitment, journeys and attempted journeys of majority of the Indians to become a part of the narrative of the Islamic State can be linked to the outfit’s Declaration of the Caliphate in June 2014. Travel of four youths from Kalyan, Maharashtra to Iraq to join the Islamic State is probably the most known episode in the short history of outfit’s designs on South Asia. That took place within two months after the IS caliphate declaration. Similar is the case of two college students from Kerala who went missing from their homes in July 2014 and landed in Syria to join the Islamic State. The declaration also marked the beginning of the waving of the Islamic State’s flags in Kashmir. Subsequent months saw a further rise in mobilisation efforts that resulted in further recruitment.

Secondly, IS recruitment peaked after the outfit’s declaration of the Wilayat Khorasan in January 2015. Coinciding with the declaration, at least two groups of men and women attempted to join the outfit. Fourteen engineering students from Hyderabad attempting to travel to Syria were arrested at the Hyderabad airport on 6 May 2015. Similarly, nine Indians who had travelled to Istanbul on tourist visas and attempted to cross the border into Syria, were deported to India by Turkish authorities on 30 January 2015. The group included 24-year Ibrahim Nowfal from Hassan and Javed Baba from Telengana. The other seven members belonged to a Chennai based family identified as Muhammad Abdul Ahad, his wife and five children.

Thirdly, while from all over the world, the Islamic State has managed to recruits psychopaths and adventure seekers, drawn from the disaffected populations, in India, mostly the young and educated men from well do families appear to have fallen to its radical pulls. Anwar Hussain, a minivan driver from Bhatkal, who was killed near Kandahar, was the only one among the Indian IS aspirants who came from a humble background. A large number of them had western education. Muhammad Abdul Ahad finished his Masters Computer Science from Kennedy-Western University, California; 32 year Salman Mohiuddin from Hyderabad had an MS degree from Texas Southern University in Transportation Planning and Management; the 19-year old Jabin from Kerala pursued school education in UAE; and the lone Kashmiri to have joined the outfit, the 26-year old Adil Fayaz was an MBA student at Queensland University in Australia. The rest including the four youths from Kalyan, Haneef Waseem, the 26 year old from Hyderabad, who had been killed while fighting on behalf of the IS, and many others were engineering or college students. The attraction of the Islamic State among the educated and tech savvy has been profound.

Fourthly, a definite linkage has developed between existing home grown Islamist terrorist outfits and the Islamic State. Membership of the former has overtime facilitated the shift to the Islamic State. Among the five Indians killed while fighting on behalf of the outfit are Abdul Qadir Sultan Armar from Bhatkal and Bada Sajid, both leaders of the Students’ Islamic Movement of India (SIMI)/ Indian Mujahideen (IM). Armar’s brother Shafi Armar is currently the emir of Ansar al-Tauhid (AAT), a recruitment organization for the Islamic State based in Pakistan. The IM has lost ground within India and its Pakistan based leadership has fractured with one faction joining the Islamic State. The fact that a radical past forms a useful background to join the Islamic State facilitates the transition from the existing and yet ineffective organisation was also clear from the busting of the five member Islamic State module in the country led by Imran Khan Muhammad Yusuf. Yusuf was arrested along with four others from Ratlam in Madhya Pradesh in April 2015. A drop out from a undergraduate business course he was a member of a Islamic proselytising and charity group.

Fifthly, in all the known cases so far, online radicalisation indeed played an important part. Islamic State social media pages and Islamist forums have been the usual meeting points between recruiters and these youths. The arguably coherent and learned interpretation of Islam deeply rooted in prophetic methodology as well as its regressive practices have found reverberations in the youths attempting to join the outfit. This appeared to have impacted the youths with an inclination towards more puritanical sect of Islam. Areeb Majid, for example, told his interrogators that he was a follower of the Ahl-e-hadith sect and rebelled against the use of Bollywood songs during religious congregations and was impressed by Fahad Shaikh (the other youth from Kalyan) when Shaikh pulled out the loud speaker from a vehicle during a religious procession to stop Bollywood music from being played. Before he left for Iraq, Majeed even left a note censuring his family for “sinning”, “living luxurious lives”, “watching television” and “not praying”. Zuber Ahmed Khan, a journalist from Mumbai, who was arrested on 7 August 2015 for attempting to join the outfit, wrote on his blog that “the IS does not betray those who help it on the basis of religion.”

Sixthly, such online radicalisation has further been backed up by a rather large group of facilitators/ recruiters who not only spotted the potential recruits, motivated them and even made logistical arrangements for their journey. Mansoor Biswas, an employee in a multinational firm who handled the twitter handle @Shamiwitness to propagate IS-related news is well known. While Biswas, arrested in December 2014, remained the only known amplifier of Islamic State related news in India, people like Haja Fakkurudeen Usman Ali, a Tamil Nadu resident and Afsha Jabeen, a lady from Hyderabad have played important role in directly recruiting people for the Islamic State. In case of the unnamed youth from Azamgarh mentioned in the beginning of the article, an Indian origin recruiter based in the UAE for the 25 years was instrumental. While the young man was believed to have been drawn to the Islamic State propaganda while surfing internet websites and chatrooms, it was through the UAE contact that he finalised his plans of travelling to Turkey. The intelligence agencies have a list of about 55 such facilitators/ recruiters. It is possible that most of these recruiters are part of the long established recruitment network associated with outfits like the IM/SIMI.

Lastly, majority of the recruitment and mobilisation have indeed taken place within regions with a long history of Hindu-Muslim divide, radicalisation and from the traditional recruitment grounds of proscribed outfits like the SIMI and the IM. A large number of these places are located within the states which also have witnessed Islamist terrorist incidents. Thus, a definitive linkage between existing religious divide, growth of extremism, and an existing radicalisation and mobilisation network can be established.

*Dr. Bibhu Prasad Routray is Director of Mantraya.org