Turkey’s Erdogan Accused Of Playing Politics With Pandemic – Analysis

A ban on city authorities from aiding those worst hit by the economic fallout of COVID-19 is a thinly-disguised attempt to exact revenge for a string of losses in local elections last year, critics of Turkey’s ruling party and president say.

By Hamdi Firat Buyuk

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, city authorities in Turkey’s most populous city, Istanbul, have provided more than 3,600 families with aid of 300 lira [41 euros] and another 6,400 families with 600 lira each to help offset the financial impact of the coronavirus crisis.

The money was raised from donations in a city run since mid-2019 by opponents of Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party, AKP.

But the campaign to help those most in need lasted only a day and a half, the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality, IBB, told BIRN, because the Turkish government banned municipalities from collecting donations and distributing provisions. And that’s not all.

“2.7 million Turkish lira [365,000 euros] cannot be used since the government blocked our bank accounts,” the IBB said.

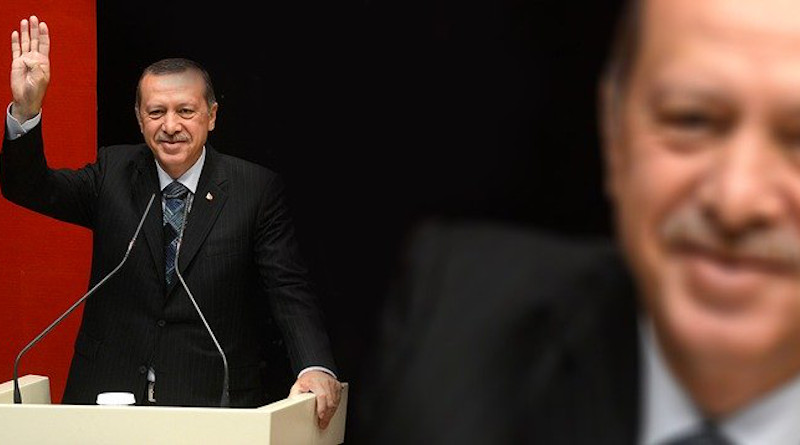

Critics of the AKP and its leader, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, say they are exploiting the COVID-19 pandemic to exact political revenge for the party’s loss of most major cities in Turkey to the opposition in last year’s local elections.

Erdogan, they say, is determined to prevent the likes of Istanbul mayor Ekrem Imamoglu from making further gains.

“Local leaders, where the pandemic is centred, come to the fore in every country,” said political scientist Sezin Oney.

“All eyes are on New York in the US, Bergamo in Italy and Istanbul in Turkey and naturally Istanbul’s mayor, Ekrem Imamoglu, comes to the fore,” he said.

“Losing Istanbul was very painful for Erdogan and this pain is felt again in such a crisis.”

Erdogan’s rule threatened by Istanbul mayor

According to official figures, as of April 21 Turkey had more than 95,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19, lifting the country above China to become the seventh most-affected country in the world. Some 2,259 have died.

On April 20, Erdogan announced fresh measures to curb the spread, including a four-day curfew. Earlier in the month, the Interior Ministry banned municipalities from collecting their own donations to help those most affected by the pandemic, and blocked the bank accounts used to do so.

Erdogan has taken aim at opposition-run municipalities, accusing them of forming a “parallel state” and using “terrorist” methods to undermine the government’s efforts. All measures, he said, must be taken and run by the central government, which has launched its own campaign to raise donations. “Fighting the pandemic requires central planning and strong coordination,” Erdogan said on April 20, calling on opposition-run municipalities to halt their “political show”.

Analysts say the government’s steps mark the continuation of a high-stakes political battle being waged since the AKP lost power over a string of major Turkish cities, including the economic and cultural hub Istanbul, the capital Ankara, and other major industrial, tourist and agricultural centres such as Izmir, Adana, Antalya and Mersin in elections in March last year.

Electoral authorities called a re-run in Istanbul, which Imamoglu won in June with a margin of more than 800,000 votes.

Imamoglu, a member of the opposition Republic People’s Party, CHP, is widely seen as the only political figure capable of threatening Erdogan’s increasingly authoritarian 18-year grip on power. Erdogan himself was a mayor of Istanbul.

“In any country in the world a city mayor who distributes bread and provisions would not be treated as the leader of a terrorist organisation,” Imamoglu said on April 22. “We have no other priority than serving the people.”

Journalist Leven Gultekin told his weekly show on Media Scope TV: “Erdogan cannot bear that the opposition uses the same methods [to rise in politics],”

“Opposition-run municipalities are banned from distributing provisions and bread with unlawful, unethical decisions,” he said. “Erdogan bans municipalities which can help millions of people in need, purely out of political calculation.”

The opposition CHP accused Erdogan of waging a campaign of “hate and revenge” against municipalities run by the party.

“Our country is not just fighting the pandemic; it is fighting the hubris syndrome of the palace,” said CHP spokesman Faik Oztrak, in reference to Erdogan’s presidential palace.

‘Is it a crime?’

The Turkish government has fought to keep control of information reaching the public over the spread of the novel coronavirus and the impact on the health system and economy, but questions persist over the accuracy of official figures.

The pandemic has come on top of a string of political and economic crises for Erdogan that have drained state coffers.

“According to our research, 60 per cent of Turkish citizens do not have any savings to use in an extraordinary situation like the pandemic,” said Oney. “Many people rely on daily income and they eat what they find that day.”

The political landscape in Turkey is highly polarised, she said, and the conflict between Erdogan and the opposition-run municipalities is only making the situation worse. “This conflict undermines the response to the pandemic,” Oney told BIRN. “People are losing their loved ones and economic problems are rising.”

In Istanbul, city authorities told BIRN that they have distributed provisions and hygiene packages to 7,000 families and plan to make similar donations to another 500,000.

In Ankara, the opposition-run municipality also announced on April 21 that it will distribute 100,000 aid packages per week.

Responding to Erdogan’s criticism, the opposition mayor of the southern port city of Mersin, Vahap Secer, told RS FM radio: “We increased our bread production capacity and we were distributing 35,000 free loaves for those who need it but the government banned us from doing so.”

“We helped those who say they need help. Is it a crime?”