Maintaining The Balance Of Power In Southeast Asia And East Asia – OpEd

Hans J. Morgenthau, the father of realism in international relations, in the collection of his essays Truth and Power called the 21st century the ‘Asian century’ envisioning China’s rise and the consequent Sino-US rivalry (Sempa). The East Asian and Southeast Asian states have long maintained the status quo in the region, preserving the balance of power.

However, with the changing dynamics such as Chinese increasing aggressiveness and Russian revisionist designs, the region is most likely to experience turbulence in the status quo, leading to shifts in the balance of power. For this very reason, Southeast Asian and East Asian actors such as Japan and South Korea are looking to acquire weapons and armaments and revise their self-defense strategies to protect their interests and ensure their survival, the key assumptions of Morgenthau’s realism theory.

In classic realism, Morgenthau asserts that politics is rooted in selfish human nature, interests are defined in terms of power, and ethics have little role to play in international politics where states are the rational, unitary actors struggling for power (Cristol 239). Under such assumptions, Morgenthau explains that “the aspiration of power on the part of several nations, each trying to maintain or overthrow the status quo, leads to necessity, to a configuration that is called the balance of power and to policies that aim at preserving it” (Schweller 2).

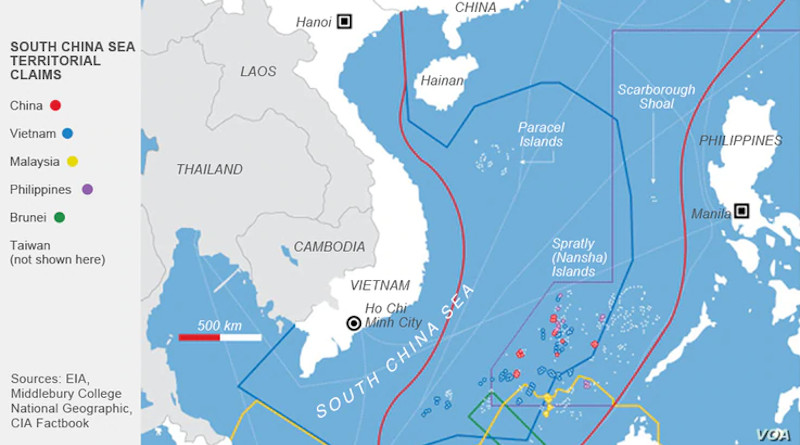

As Morgenthau predicted, although the United States acquired supreme naval and air power, the Chinese are predominant on the land in the Asian region (Sempa). However, in its ‘rising power’ trajectory, China has significantly added to its land and naval power so much so that the South China Sea dispute can be defined in terms of both a land and maritime conflict. Chinese claims over the South China Sea under its historic nine-dash line theory overlap with the exclusive economic zones of Southeast Asian states such as Vietnam, Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, Taiwan, and also Indonesia given the increasing tensions in the North Natuna Sea. While all these other parties govern their maritime policies by the United Nations Convention on the Laws of Sea (UNCLOS), China is not a signatory to UNCLOS and so, justifies its building of artificial islands, hydrocarbon exploration, and naval exercises (Rubiolo 117).

China aims to reshape the balance of power in Southeast Asia and the wider East Asian region to override the American hegemonial position in Asia and present itself as a regional power. To protect their interests, the Southeast Asian states are allying with each other and with the U.S. to preserve the status quo and prevent a military conflict in the region (Mastro).

Similarly, in the wider East Asian region, the historic foes – South Korea, Japan, and Russia – are becoming prominent actors in geopolitics. With the Russian invasion of Ukraine, tensions have built up on the Korean Peninsula with North Korea launching new missiles and weapons every other day. Under such intense circumstances, South Korea is looking to increase its military potential through internal balancing as well as shoring up its alliances with external actors, even Japan (Kaplan). South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol recently asserted that if the North Korean threat continues to grow, South Korea might build its nuclear weapons or ask the United States to redeploy troops and weapons in the Korean Peninsula (Sang-Hun). While the Ukraine war is a major driving force, increasing Chinese belligerence is also a strong motivating factor behind this stance.

On the other hand, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has marked Japan’s return to geopolitics as Japan seeks to revisit its pacifist constitution. In early 2023, Japan has revised significant parts of its post-1945 security posture and aims to implement a more lean and forward security policy that allows Japan to rely less on the United States and enhance its power based on its economic capabilities, strategic regional position, and military capacity (Hornung). In addition to a new self-defense approach adopted by South Korea and Japan in the wake of increasing Russian revisionism and Chinese assertiveness, both countries also attended the 2022 NATO summit as “Asia-Pacific partners” (Gubin). Moreover, the recent visit of NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg to Japan further asserted closer NATO-Japan relations as Stoltenberg affirmed, “No NATO partner is closer or more capable than Japan” (NATO).

The current Southeast Asian and East Asian powerplay confers Morgenthau’s realist assumptions of power struggle and survival in the Asian century. While Morgenthau well predicted the rise of China as a strong opposing force to the U.S. in the Asian region, Russian revisionism and North Korean nuclear aggression however are added contributing factors to the current balance of power dynamics in the region. While the claimants in the South China Sea dispute are struggling for their maritime rights against Chinese assertiveness, Japan and South Korea in East Asia are struggling to protect their sovereignty and increase their self-defense capabilities against threats posed by Russia, China, and North Korea.

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own.

References

- Cristol, Jonathan. “Morgenthau vs. Morgenthau? “The Six Principles of Political Realism” in Context.” American Foreign Policy Interests, vol. 31, no. 4, 2009, pp. 238-244.

- Gubin, Andrey. “The East Expands into NATO: Japan’s and South Korea’s New Approaches to Security.” Russian International Affairs Council, 11 Aug. 2022, russiancouncil.ru/en/analytics-and-comments/analytics/the-east-expands-into-nato-japan-s-and-south-korea-s-new-approaches-to-security/. Accessed 10 Feb. 2023.

- Hornung, Jeffrey W. “Japan’s Long-Awaited Return to Geopolitics.” Foreign Policy, 6 Feb. 2023, foreignpolicy.com/2023/02/06/japan-china-taiwan-russia-geopolitics-defense-security-strategy/. Accessed 10 Feb. 2023.

- Kaplan, Fred. “Why Japan and South Korea Are Arming Up.” SLATE, 31 Jan. 2023, slate.com/news-and-politics/2023/01/japan-south-korea-remilitarization-biden-russia-ukraine.html. Accessed 10 Feb. 2023.

- Mastro, Oriana S. Military Confrontation in the South China Sea. Council on Foreign Relations, 2020. www.cfr.org/report/military-confrontation-south-china-sea. Accessed 10 Feb. 2023.

- NATO. “Secretary General at Keio University: NATO-Japan partnership is growing stronger.” 1 Feb. 2023, www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_211389.htm#:~:text=In%20a%20speech%20at%20Keio,%2C%E2%80%9D%20said%20Mr.%20Stoltenberg. Accessed 10 Feb. 2023.

- Rubiolo, M. F. “The South China Sea Dispute: A Reflection of Southeast Asia’s Economic and Strategic Dilemmas (2009-2018).” Revista de Relaciones Internacionales, Estrategia y Seguridad, vol. 15, no. 2, 2020.

- Sang-Hun, Choe. “In a First, South Korea Declares Nuclear Weapons a Policy Option.” The New York Times, 12 Jan. 2023, www.nytimes.com/2023/01/12/world/asia/south-korea-nuclear-weapons.html. Accessed 10 Feb. 2023.

- Schweller, Randall L. The Balance of Power in World Politics. Oxford UP, 2016.

- Sempa, Francis P. “Hans Morgenthau and the Balance of Power in Asia.” The Diplomat, 25 May 2015, thediplomat.com/2015/05/hans-morgenthau-and-the-balance-of-power-in-asia/. Accessed 10 Feb. 2023.