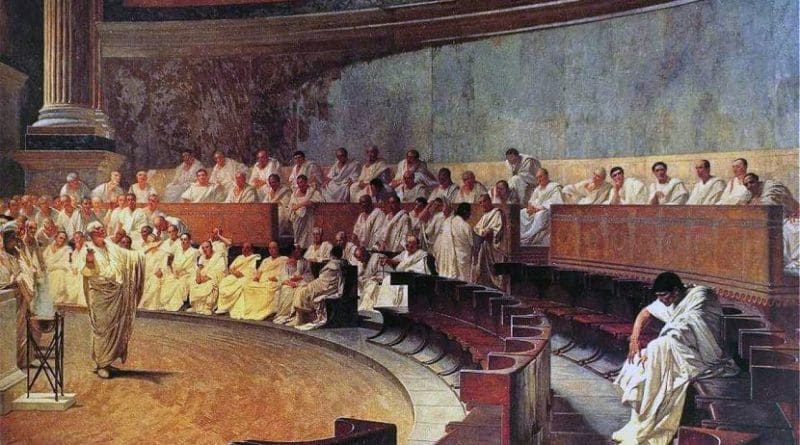

In Ancient Rome Insults In Politics Knew Hardly Any Boundaries

According to historians, political debates in ancient Rome were conducted with great harshness and personal attacks, which were in no way inferior to some of the hate speech on the Internet.

“The attacks, also known as invectives, were an integral part of public life for senators of the Roman Republic,” explained ancient historian Prof. Dr. Martin Jehne of Technische Universität Dresden. At the 52nd Meeting of German Historians in Münster in September, in a section on abuses from antiquity to the present day, he will speak about the culture of conflict in ancient Rome.

“Severe devaluations of the political opponent welded the support group together and provided attention, entertainment and indignation – similar to insults, threats and hate speech on the Internet today.”

According to Jehne, the highly hierarchical Roman politics sounded rough, but was not without rules.

“Politicians ruthlessly insulted each other. At the same time, in the popular assembly, they had to let the people insult them without being allowed to abuse the people in turn – an outlet that, in a profound division of rich and poor, limited the omnipotence fantasies of the elite.”

Politicians and the public hardly took abuse at face value. Even if the comparison with today is partly misleading, said Jehne. “A certain Roman robustness in dealing with abusive communities such as AfD or Pegida could help to reduce the level of excitement and become more factual.”

According to the historian’s findings concerning ancient Rome, withstanding and overcoming insults can ultimately have a politically stabilizing effect. The slander in the Roman Republic (509-27 BC) went quite far.

“The famous speaker and politician Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC), for instance, when he defended his supporter Sestius, did not shrink from publicly accusing the enemy Clodius of incest with brothers and sisters,” said Prof. Jehne – a sexual practice that was also considered illegal in Rome. “Clodius, in turn, accused Cicero of acting like a king when holding the position of consul. A serious accusation, since royalty in the Roman Republic was frowned upon.”

Thus, as the historian emphasizes, there were hardly any limits in the political dispute. This differs from today, where intensive thought is given to the limits of what is permitted in debates on the street or on the web.

“The Romans didn’t seem to care much. There was the crime of iniuria, of injustice – but hardly any such charges.”

“No murders to avenge honour”

According to the historian, the Romans of the city were proud of their biting, ruthless wit at the expense of others.

“They considered this an important part of urbanitas, the forms of communication of the metropolitans, in contrast to the rusticitas of the country bumpkins.” They made a downright boast of the slander flourishing in the city in particular. “When you were abused, you stood it, and if possible, you took revenge.” Invective opponents often worked together again soon afterwards and maintained normal contact. The political climate remained reasonably stable: murders to avenge honour were only committed in the exceptional situation of a civil war.

According to Prof. Jehne, the fact that the people were excluded from the harsh treatment of senators in political arenas, but were themselves allowed to insult and catcall the political elite, shows that the politicians of the Republic, “undisputedly recognised the popular assembly as a political people”.

Measured by today’s democratic electoral procedures, it was a maximum of three percent of those entitled to vote, “but the senators saw in it the people as the decision-making authority for the community”. In the debate about the agricultural law in 63 BC, for example, Cicero tried to persuade the people to change their minds.

“But should he not succeed, he promised to bow to the people and change his opinion.”

Those who questioned the people as a decision-making body risked the crowd roaring up and storming the rostra.

“However, this power of the people was only valid in official political communication arenas,” emphasized Jehne. “If members of the ‘common people’ did not make way for the senators and their entourage in the streets in time, they were approached rudely and by no means courted.”

“A little more serenity in current debates”

Since investigating abuses in the Roman Republic, Jehne is more relaxed about today’s debates in social networks.

“The outrageous overstepping of the boundaries of the abusive communities such as Pegida or AfD, with which they want to integrate their supporters, are amplified in resonance by the exuberant media diversity. My research, however, has led me to considerably reduce my level of excitement at new abuses in the present – at any rate, it was not the abuses that caused the downfall of the Roman Republic.”

At the 52nd Meeting of German Historians in Münster, together with the Dresden historians Prof. Dagmar Ellerbrock and Prof. Gerd Schwerhoff, ancient historian Prof. Dr. Martin Jehne will head the section “Invective Divisions? Excluding and Including Dynamics of Abuses from Antiquity to Contemporary History” on Thursday, 27 September. In addition to the abuses in the Roman Republic, abuse between clergy and lay people in the Christian Middle Ages, abuses among enlightened philosophers as well as the situation in the USA in the 1960s and in colonial Africa will also be examined. The backdrop is the research at the Collaborative Research Centre 1285 “Invectivity. Constellations and Dynamics of Disparagement” at Technische Universität Dresden, where Prof. Jehne heads the subproject “Invectivity in arenas of ritualised communication in the Roman republic and imperial era”.