China’s Belt And Road Runs Aground In The Philippines – Analysis

By Michael Hart

In late July, the four-lane Estrella-Pantaleon Bridge opened to traffic over the Pasig River in Manila, offering a new route between the urban centers of Makati and Mandaluyong within the Philippines’ congested capital. Around 50,000 vehicles will pass over the bridge each day, which was built by the China Road and Bridge Corporation under the umbrella of both Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative and Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte’s keynote ‘Build, Build, Build’ domestic infrastructure program.

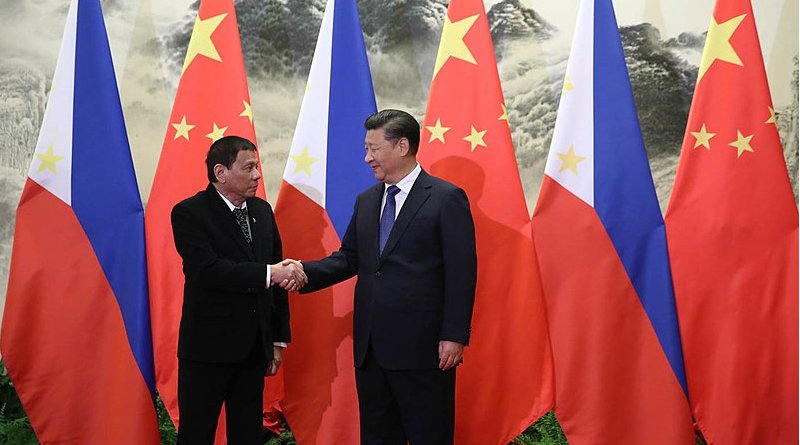

Duterte—who attended an inauguration ceremony along with the Chinese ambassador—hailed the opening of the bridge, and after a virtual meeting with Xi Jinping on 27 August said he envisaged the completion of more key China-funded infrastructure projects, ranging from flood control to railways. Yet many projects envisaged at the start of Duterte’s six-year presidency—when he departed a state visit to Beijing with US $24bn in investment and loan deals—are unfulfilled as his term nears its end.

‘Belt and Road’ and ‘Build, Build, Build’

Of the loans and investment pledges secured during the 2016 visit, US $15bn reflected company-to-company deals while US $9bn was in the form of expected loans by Chinese banks either for specific projects or to Philippine firms. At least 17 memoranda of understanding or other deals were signed, covering a wide array of projects in sectors ranging from transportation and manufacturing to renewable energy. Proposed Chinese projects spanned the entire 1,850km length of the Philippine archipelago.

In Beijing, Duterte lauded a fresh start for economic ties between the Philippines and China, having announced his “separation” from traditional close ally the United States in front of Chinese leaders. Xi Jinping responded to Duterte’s overture by lifting restrictions on Philippine banana and pineapple exports, which had been imposed years before amid worsening tensions in the South China Sea. The Philippine president, seeking support from Xi, has largely been content to push those disputes aside.

It appeared the path was forged for an economic boom to the tune of the two leaders’ grand plans: Duterte’s vote-winning ‘Build, Build, Build’ program — which has placed upgrades to the Philippines’ overworked national infrastructure near the top of his administration’s priorities — was to receive a boost in the form of long-term Chinese financing under the Belt and Road Initiative. At the western edge of the Pacific, the Philippines marked a lucrative stop along the envisaged Maritime Silk Road.

The mixed fortunes of Chinese projects

In the five years since, however, projects have been slow to get off the ground. In 2020, US $620m of official development assistance from China was disbursed in the Philippines, out of US$4.6bn set aside for current projects, most of which remained at the procurement stage. The Philippines hopes to add another US $1.9bn to that total shortly, with finance undersecretary Mark Dennis Joven remarking last month that the Export-Import Bank of China was evaluating loans for another three major projects.

Finance secretary Carlos Dominguez recently voiced approval in the Philippine Daily Inquirer of China’s implementation of projects that were already underway, but acknowledged that “massive” deals came with bureaucratic red tape, in particular citing “difficulties in getting approvals,” and in construction firms from both countries involved in the joint ventures “understanding each other.”

The fortunes of three China-backed infrastructure projects in 2021 demonstrate these disparities:

In January, a deal was approved for a US $940m freight railway linking two former American military bases in Luzon, the Philippines’ wealthy northern island. The 71 km single-track line will take around four years to build, and when complete will link commercial zones at Subic Bay and Clark Air Base to ports and airports, smoothing the transit of goods and boosting growth in an existing economic hub.

Just days later, the China Road and Bridge Corporation announced a US $400m contract at the other end of the country, to construct a 4 km oversea bridge connecting Mindanao’s Davao City with Samal Island. The four-lane structure will allow vehicle traffic to cross the narrow Pakiputan Strait, boosting trade and tourism in the region. The two projects look set to make a big difference in their localities.

Not all projects have secured the green light, however. In Cavite, the provincial government earlier this year cancelled a decision to award a multi-billion-dollar airport upgrade job to a consortium led by the China Communications Construction Company, scuppering one of the most expensive China-backed projects in the Philippines. Local governor Juanito Victor Remulla told Reuters that the firms in the consortium were “deficient in three or four items” and “not fully committed” to the project.

Remulla insisted that the decision to scrap the contract was unrelated to the blacklisting of Chinese firms involved in the Sangley Airport project by the United States, over their alleged role in building military installations on disputed reefs in the South China Sea. Duterte has rejected scrapping deals with these firms, vowing that infrastructure projects are in the national interest and must proceed.

Belt and Road limited in the Philippines

In all, Belt and Road presents a mixed picture in the Philippines. Only three major China-backed infrastructure projects are set to be finished by the end of Duterte’s term in mid-2022. More are in the pipeline, but much will depend on the winner of next year’s election. Duterte is set to run as the vice-presidential candidate for the ruling PDP-Laban, alongside either Bong Go or his daughter, Sara Duterte-Carpio, the current mayor of Davao. A victory for the Duterte camp would provide a chance for delayed projects to go ahead, while an opposition win would leave the status of projects unclear.

Whatever the outcome, China-funded projects in the Philippines will be more scattered and smaller in scale than elsewhere in Southeast Asia, where massive Chinese investment in places like Laos has brought fears of a “debt-trap.” An expansive mega-project like the pan-Asian railway, which Beijing envisages to run through Laos, Thailand, and Malaysia en route to Singapore is not a prospect in the Philippines, due to its island geography and proximity from China. In the Philippines, Beijing also has less urgency as it has less to gain strategically than it does in its nearest Southeast Asian neighbors.

As a result, Duterte’s shift toward China has been accompanied by an increase in investment linked to the Belt and Road, but not on the massive scale witnessed elsewhere in the region.

This article was published by Geopolitical Monitor.com